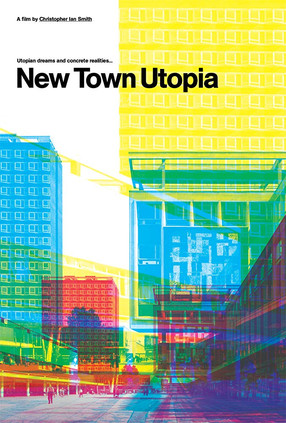

It's easy to be cynical about the history of planning in Britain, and especially easy to be scornful of those well-meaning but usually flawed efforts to build new communities which skirt neatly around the errors and problems of the past. When these developments arise - the garden city movement, the planned worker's villages of Bournville or Port Sunlight, or the Prince of Wales' village at Poundbury - they nearly always lack any kind of genus loci. In the same way, you'll often hear the New Towns which arrived in post-war Britain via a long-winded commission and various acts of parliament, lazily described as 'soul-less'. These towns were an attempt to finally eradicate the Victorian slums and to encourage people to move out of the bursting city centres where housing which hadn't been bombed out-of-use was in short supply. Like a great deal of post-war planning and architecture, they divide opinion sharply. They mixed a peculiarly British take on a socialist utopia with utilitarian simplicity and often appealed to a higher nature in their residents through the provision of arts centres, theatres and the like from the outset. But, these were consciously designed places which were still rare in a country which was struggling slowly out of the previous century with its progress hampered by two destructive wars. Provided with an unprecedented tabula rasa in greenfield sites and bomb-ravaged urban wastelands, they also deployed some of the newest styles of architecture and means of building - architecture which would have never squeezed past a fussy old planning committee in normal circumstances. This, along with the social changes which the 1970s and 80s brought to the country renders a particular image of a New Town today: concrete, streaked with rust, shuttered stores and abandoned civic pride. Is that unfair or inaccurate, or is it lazy to take this surface-dressing as a proxy for the lives of people living in these places? This film delves right into these perceptions and tests them over the course of a surprisingly human, affecting documentary.

I grew up in Redditch - a second-wave New Town, built when the cash was running out and faith in the project was waning. The Development Corporation was less ambitious than those who'd forged ahead earlier and satisfied itself with a sweep of new housing estates on the town's eastern green flank with some impressive American-style expressways to link them to the town's core. In the centre, Redditch saw the building of a new shopping centre/bus terminus combination which not only destroyed the original town centre street-pattern but mocked the locals' affections by parroting the old streets in the named 'walks' of the Kingfisher Centre. Basildon however, came earlier in the project - and was built with a greater sense of purpose and utopia it seems. It's position on open Essex land attracted industry, and numerous firms moved their plants to the new town. The future looked bright for this curious newcomer to the flat open spaces of estuarial Essex. They didn't build a railway station - people would live and work in the town, so who needed to get away? Over the course of New Town Utopia, Christopher Ian Smith meets the people who moved here, were born here and have in some cases tried to get away over the course of their lives. Many have been driven away by unemployment as local industry declined in the 80s, or have tried to follow their fortunes elsewhere - but a surprising number return. The film is built around the voices of these generations of Basildonians, their aspirations, dreams and impressions of life in the town. These are most often set against images of Basildon today: Patrick Keiller style unpeopled shots of long dual-carriageways, crumbling estates, litter-strewn footpaths. Basildon feels like a time-capsule of British idealism, a sort of mid-century sampler of design flourishes and municipal vernacular that wasn't to quite take to the mainstream. It is photogenic for the wrong reasons, impressive in its bleakness.

Throughout the film though, there is a surprising sense of something lost - something which perhaps these citizens only recently discovered they even had: a sense of being from Basildon. This unexpected attachment to the much-disliked newcomer features most strongly in two sequences: the first where locals discuss the arts scene, and the facilities which they have lost, regained and reused to continue a strong emphasis on creativity in a town which is all-too-often the uncultured and unreconstructed butt of jokes. The second occurs when the talking heads on screen consider the reputation of Basildon as a tough, violent place. There is an uncomfortable mix of dismay and pride in the reactions when they tell people they're from Basildon. But there is a concern in all of them, young or old, that the sense of being from the town is ebbing away: London draws everything in, people work in the city and sleep in Basildon. Things are changing again here, and they now have a railway station.

The film explores a further uncomfortable divide: the impact of Thatcherism on Basildon. Older residents bemoan the loss of the industries which moved with them to Basildon, which they relate specifically to the government's policies. In fairness though, the local factories (tobacco and camera film) were not publicly owned and were ill-starred already by future obsolescence perhaps? The locals also celebrate the ability to purchase their own homes and the chance to create roots in the new town. A retired trade union organiser and councillor is upset that his children don't want to vote Labour and thinks that weak unions mean weak businesses, while a middle-aged Basildonian admits with some embarrassment that the changed economy of the 1980s gave him the chances he needed to get ahead. There is a shame in seeing the positive changes in society - it just doesn't fit the idea of a worker's town which they were encouraged to support. Throughout the film, Jim Broadbent intones the words of Lewis Silkin MP, Atlee's housing minister who believed that newly created places could instil a Matthew Arnold like 'sweetness and light' in population which was not divided by class or profession, by age or race. Arts, culture and green space would be the engine of this change - and it's fair to say that from the moment the Basildon Development Corporation handed over the town to the Local Authority, it's these very things which have suffered: gradually chipped away in the interests of reduced costs and increased density.

The film concludes that while the placemaking and aspirational building of Basildon hasn't entirely worked, that Silkin was almost right: Basildon today, despite being in the overwhelmingly 'White British' band of population which stretches east of the Capital, is a placed of mixed experiences, backgrounds and outlooks. It's impossible to imagine the infectiously optimistic Hippy Joe - 'Essex' patch stitched into the groin of his dungarees - wanting to move away from the community of musicians and fans he runs a club for, but it's equally difficult to expect the current generation of young Basildonians - whether future poets and musicians, lawyers or bankers from wanting to be limited by the boundaries of this curious place. This film treats all of these voices with dignity, decency - and most importantly, it allows them the space to expand on their views without descending to soundbite and snapshot.

Scouting for Turkeys: Enfield to Epping Forest

Posted in London on Saturday 7th July 2018 at 10:07pm

It was a faintly ridiculous proposition, but I am it must be said, a creature of habit... I'd long ago booked the journey to London for this walk - speculatively scooping up cheap rail tickets in advance knowing that I'd probably end up planning the walk hastily at the last moment. I hadn't figured on a holiday to Germany nestling into the previous week, our return less than 24 hours beforehand necessitating a quick journey west from Heathrow, a little sleep and then an early return eastwards. I arrived at Paddington a little dazed by the whirl of travel and disarmed by the sheet of hot, dry air which hit me on leaving the air-conditioned railway carriage. True to form, I'd planned my itinerary for the day entirely on the fly, largely between naps on the train: I would head for the northern heights and walk the course of the Turkey Brook to the Lea. Beyond there? The valley had never really let me down, so it felt safe to see where I ended up without further planning. Plunging into the Underground for the journey to Kings Cross was strangely reassuring: after a week of being half-understood and perpetually a little disoriented, I was on more solid ground, back in the conversation-free zone of London. Trains at Kings Cross were reassuringly disrupted, the queue at the coffee shop frostily polite. I don't travel internationally often and I was struck by how doing so refocuses me on how English I am. Not, or at least I hope not, in that mildly racist and stereotypical football-supporting way. Not even today when a display of national pride was mandated by the World Cup. More in a sense that I'm culturally built for uncomfortable silences, frequent apologies and a background level of mild irritation. Already, before I'd really set off on the day's excursion I'd seen all of this. As I slalomed between disgruntled commuters trailing suitcases with little care and even less attention, I spotted that my cancelled train had been reinstated to run later than planned. I navigated to the platform and settled into the cool, quiet carriage. All too soon I was decanted at Finsbury Park to await the next connection to Gordon Hill. Cranes shadowed the parched platforms, swinging eerily and silently with payloads of ironwork for the two curved towers which were climbing into the air between the station and the city. Workmen ambled around the site - no need for undue haste at Saturday rates. Finsbury Park shimmered under the haze, the distant Emirates Stadium like a hovering red mirage. I slapped on suncream, guzzled coffee, jammed water bottles into the pouches of my rucksack. It felt good to be heading out of the city...

I'd been to Gordon Hill before - or at least the station, on a quest for the elusive third platform a decade ago - and I lazily remembered it as a sleepy, dormitory suburb of little note. The area was laid out in the 1860s on the land which formerly accommodated Gordon House - named for a colourful early occupant Lord George Gordon. Gordon was by most accounts, a skittish and inconsistent character who often took up causes for the sake of opposing the common view, but who also constantly railed against oppression and injustice. A staunch supporter of American independence and religious freedom, he paradoxically opposed more lenient treatment of Catholics - leading a march of 50,000 to Parliament in 1780. Following this, the so-called Gordon Riots resulted in the burning of Newgate Prison, damage to much property belonging to 'papists' and the death or injury of many hundreds of Londoners after the Army was summoned to put down the insurrection. Gordon was sent to the Tower of London for treason but was released after a trial where his Cousin, Lord Erskine, defended him by claiming the charge was a grievous over-stretching of the Treason Act 1351 and painting Gordon as seeking only to defend rather than injure his country. Gordon converted to Judaism and lived somewhat secretively in the home of a Jewish woman in The Froggery - a notorious slum in a dank and marshy area of Birmingham now buried under the equally benighted New Street Station. Required but unable - or perhaps unwilling - to provide securities and sureties for fourteen years of good behaviour, Gordon was finally imprisoned in Newgate where he became a popular figure providing wise counsel among fellow inmates, who greatly mourned his death in 1793 from typhoid contracted while imprisoned. Throughout his imprisonment, Gordon refused the support of his influential family in extracting him from the predicament which cost him his life. Dickens immortalised Gordon's demise in Barnaby Rudge, which takes the riots and subsequent events as its setting:

He had his mourners. The prisoners bemoaned his loss, and missed him; for though his means were not large, his charity was great, and in bestowing alms among them he considered the necessities of all alike, and knew no distinction of sect or creed. There are wise men in the highways of the world who may learn something, even from this poor crazy lord who died in Newgate.Charles Dickens - Barnaby Rudge, 1841

Any trace of Gordon's home on Enfield Chase was gone - the land now the sleepy repose of the dead in Lavender Hill Cemetery and the equally silent surrounding streets of quiet, decent homes. The suburbs here grew swiftly after the arrival of the railway in 1910 and many of the streets are rather modern in appearance. Stymied by the cemetery having only one entrance, I retraced my steps alongside the chapel and back onto Cedar Road. Here, four rather dour looking blocks of flats glowered over the Chase, delighting in incongruously rustic French names: Lombardy, Picardy, Burgundy and Normandy. This truly felt like the hard edge of London. To the south of me, more suburbs like this one stretched for miles, to the north little more than parkland and trees. At the next opportunity, the narrow and tree-shaded Cook's Hole Road, I turned north-west and headed a little back towards the west. A gap in the hedge led into Hilly Fields Park - a pleasantly wild stretch of public parkland which ranged along the Turkey Brook. As a gang of workmen sunbathed through a tea-break on the fringe of the park, I stepped up the pace eager to get my first sighting of water.

My entrance to Hilly Fields Park was via a path leading through unmown grasslands and tall, mature trees which creaked pleasantly in the near silence. Enfield Chase - a royal deer park - had occupied much of the land hereabouts until 1777 when the 8300 acres were divided among local bodies and landowners, adding to the already complex web of stewardship in the area. Part of the vast forest which stretched north and east of London, the Chase had likely already been emparked by 1154. It was not recorded as a Chase until the 14th century, spending many years in the ownership of the Mandeville family with the Manors of Edmonton and Enfield claiming common rights. After the arrival of the railway and the ensuing building boom, Enfield Urban District Council became concerned at the loss of recreational spaces and purchased 62 acres of land from Archdeacon Potter which became Hilly Fields Park in 1911. By 1921 a bandstand had been erected in the western, more open part of the park and brass bands provided popular local entertainment. My path intercepted the Turkey Brook as it entered the park in a thick strip of truly old woodland which wound along its banks at the foot of the park. An official path followed the edge of the trees, but I noted a less formal route along the banks of the brook under the canopy of venerable trees. Despite the dry weather and the mere trickle I'd seen forming one of its tributaries, the brook was flowing busily here, having carved a deep twisting fissure into the soft earth of the woodland. A few other walkers, and particularly their overheated, tongue-lolling dogs had made a preference for walking beside - or even within - the stream as it meandered along the valley floor. The walk was pleasantly challenging - crashing through the burgeoning undergrowth and hopping over mischievous limbs of trees fallen during the winter. It felt a world away from the industrial zones of Western Germany or the densely built southern suburbs of my recent walks. I'd had this stream on my list of walks for some time, but I'd often rejected it as not presenting a long enough diversion for a day of walking unless I somehow found a way out to the awkward-to-access source near Potter's Bar. Somehow though, the Turkey Brook had found its time and I felt ridiculously content schlepping along beside the water and navigating around the tight bends with their exposed root systems and tiny, eroded cliff-faces. Eventually though, the path crossed the brook and forced me into the exposed and sun-bleached park. I skirted the now restored bandstand and followed the path which reflected heat back at me relentlessly, already wishing I could walk closer to the water.

The path left the brook to bisect Clay Hill, a surprisingly busy and fast-flowing rat-run which proved a challenge to cross. Nearby, the former Rose and Crown was slowly reverting to a private dwelling: the fine, cottage-like buildings of the former public house were stacked with disused furnishings and shuttered, but its sagging gables and low windows still looked curiously inviting in the morning heat. The inn has a long association with local hauntings and intrigue and is much mentioned in connection with Dick Turpin, but this is likely due to its ownership by a Mr. Nott who is reckoned to be the Highwayman's grandfather. The Rose and Crown was once the focus of the tiny hamlet of Bridge Street, and sure enough, the brook passed under an old brick bridge a little north of the Inn. Eschewing the official path to the south of the brook, I crossed the bridge and turned east along Beggar's Hollow - a very old byway which is now primarily the entrance to Whitewebbs Park Golf Course. The name, while evocative in itself, is likely a contraction of Bullbeggar's Hollow, referring to a bugbear or bogeyman rather than a mendicant: "Something used or suggested to produce terror, as in children or persons of weak mind". Perhaps our modern fascination with the frisson of unexplored edgelands isn't entirely novel? The land on the eastern side of Clay Hill delights in a long history of ownership, patronage and the rise and fall of aristocrats - but was finally purchased by the Borough of Enfield in 1931 and Whitewebbs is now a mix of municipal golf course and public park. It began life as one of the historic manorial estates which fringe Hertfordshire, and was by 1570 in the ownership of Robert Huicke, physician to Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. The manor is often linked to the hatching of the Gunpowder Plot in 1605 - but this is disputed by historians of Eastbury Manor House in Barking who seek that honour. On the enclosure of Enfield Chase much of the northern part of Whitewebbs became part of Theobalds Park, while the remainder was turned over to agriculture. The manor house is now doing lowlier duty as a Toby Carvery nearby. Nothing it seems, was ever simple in the shifting band of rus in urbe around London. The brook, and with it my path curved along the boundary of Forty Hall, an estate first recorded around 1620 with a manor built during the following decades and occupied by Sir Nicholas Raynton, Haberdasher and Lord Mayor of London. Forty Hall was purchased by Enfield Council from the Bowles family in 1951, becoming in due course a museum and successful event venue. Much of the land around, designated as part of the Metropolitan Green Belt, is carefully protected with large areas left wild and not accessible to the public. The path provided along the edge of the estate was a fine one though, and well used by locals it seemed as I reached the confluence of the Turkey Brook with the Cuffley Brook, trickling in from the golf course to the west. The junction was hidden deep in the undergrowth, and it was easier to discern the dry gully nearby which was once the original course of the New River. The river originally took a dizzying meander around Enfield exploiting the natural contour of the land to reach London, but in 1859 the construction of the Docwra Aqueduct at Bulls Cross made this hard-to-maintain rural loop redundant. Having walked alongside the modern diversion of the river recently, I was struck by how narrow and rudimentary the waterless old channel seemed - but also how ambitious the aim of moving fresh water over a considerable distance had been given 17th century engineering techniques. The broad loop in the river had once provided the boundary to Forty Hall's extensive estate, a role now assumed by the Turkey Brook as it struck out east. I crossed a narrow lane near Bulls Cross where another well-maintained brick bridge spanned the brook, complete with a County of Middlesex warning notice about its unsuitability for heavy carriages or locomotives. The path continued beyond the road, a little way south of the water now, and climbed slightly to run along the edge of what had now become a surprisingly deep, wooded valley. I soon arrived at the intersection with the New River Path with the strange thrill of recognition which comes with stumbling across a familiar spot while walking a new route. The river crossed the brook in the simple metal aqueduct before heading underground to pass through the banks of the valley. Also buried near here was the 'Artificial Recharge Scheme' where around two-thirds of the New River's flow is diverted in tunnel to the reservoirs at Walthamstow. I paused to try to unravel the complex lie of the land here, while dragonflies flitted around the path, coming to rest on the deep green undergrowth. Even though the tangle of natural and man-made watercourses was almost entirely hidden from view here, there were tell-tale signs of water in the wildlife. This meeting of ways was a decision point - and the lure of the New River remained strong despite my relatively recent visit. Some ways into the city never lose their mystery it seems.

The strip of scrubby, litter-strewn land marooned between the New River and the Great Cambridge Road felt forlorn and derelict, pedestrians permitted only by the sufferance of the British Province of the Society of Jesus - although the notice on the permissive footway had been defaced to remove the final word, in effect creating a mysterious secret society in this most unlikely of places. The land here adjoins the well-tended grounds of a Jesuit school, St. Ignatius' College, but the course of the Brook remains largely wild and untouched - presumably on land stockpiled for future expansion of a school deemed 'good' by OfSTED. From the crossing of the New River, I'd been able to hear the swish and drone of the road ahead - and the long walk through quiet suburban parks made the sound seem alien and unwelcome. Between the overgrown edges of the path up ahead I could see the silver flash of hubcaps against the grimy standard-issue anti-pedestrian fencing of the road's median. The path sputtered out suddenly onto flagstones at the foot of a steep staircase to the footbridge. Cyclists were syphoned off to the south in pursuit of an underpass which apparently lay some distance away. As I clambered to the peak of the rather slender bridge which swayed gently with the effort of holding me above the traffic, I considered the impressively broad dual-carriageway beneath: this was ancient Ermine Street, the Roman road to Lincoln and York. It had begun its journey in the heart of the City of London, sluggishly pressing through the traffic of Dalston and Tottenham, edging along the wide, flat bottom of the Lea Valley and patiently awaiting its moment of escape. Suddenly, at Bruce Grove the road wheels into the suburbs and emerges from the one-way system as a classic 1920s arterial route - one of the 'Great' roads which radiated from London, strewn with modernist factory buildings and fringed by large brick villas. But the 'Great Cambridge Road' doesn't go to Cambridge anymore - at least if the sanctioned destination signs are to be believed. Only Enfield and Hertford are name-checked now, and after that? Nothing. Some signs clearly have the old destination plated over, traffic directed east to the M11 which snakes out to the northeast. The old road remains busy - still the easiest way to escape from the east of London to the north, and those in the know prefer its long, straight lines to the gently deceptive curves of the motorway. The Romans knew best it seems, and neither time nor transport policy has succeeded in downgrading Ermine Street from its primary route status. I carefully descended from the alarmingly vibrating frame of the bridge, taking the continuation of the path as it burrowed behind Enfield Crematorium, passing a sizeable fringe of the grounds which wasn't yet used for burials. A curiously unmarked series of masts, pipes and generator buildings nestled sinisterly in the undergrowth to the north of the path but probably I reasoned, had an utterly mundane purpose in a state heavy with surveillance of the least consequential things. The humid air closed in under the overgrown foliage, and the heat and stillness gave the path a malign feeling. This was part of the London Loop footpath, and while I've stumbled across - and along - many sections which were less than salubrious, this was one of the least inviting I'd found for a while. I was glad to pass under a very low railway bridge and to escape into the open once again near Turkey Street station. A corner of parkland had been recently refurbished to include a circular bench, currently in use to support the flowers and photographs of an impromptu memorial, while the brook emerged from under the rails by way of a solid brick bridge, now flowing along the street with which it shared a name.

It's hard to know exactly which came first - Turkey Street, the hamlet into which I was now walking has a long etymological history, moving from Tokestreete via Tuckhey Street to its current name in the space of around 400 years. The brook seems to have been named from the hamlet rather than in the more traditional practice, and locally remains the Maiden's Brook for some. The name appears to be derived from a family name rather than any reference to bird or country, and yet it has persisted in this form since around 1800 while the hamlet it describes has changed considerably. After a walk along the attractive banks of the brook where a terrace of houses tumble along the slope to reach the water, I emerged onto the main drag of Turkey Street. It was a seething, channel of kebab houses, bus stops and slow-grinding traffic queues. I made a crossing, mostly to avoid two bored looking Jehovas' Witnesses who were sunbathing listlessly in their button-up white shirts on the corner near the bridge. It was here that the brook begins to be tamed by mankind, squeezed into a culvert and straightened to plough its easterly path. I gingerly glanced over the bridge, sandwiched between hairdressers and takeaways, rather dreading what horrid pollution I'd discover. In fact it was what I perhaps couldn't see which alarmed me more, as a beautiful silvery adult fish gazed sightlessly up from its resting place on the riverbed appearing to have been felled by some invisible pollutant. I made a mental note to look out for any others and to report them. The suburban centre of Turkey Street sat astride the old route of the Cambridge Road - still long and straight, but now the sluggish distant cousin of the grand and aspirational arterial route nearby. I realised that I'd be in the company of the London Loop for much of the rest of my walk now, so I let the familiar signs guide me through the tense locus of overheated people and shuddering cars. I remembered once picking trains specifically to cover this suburban route, and feeling this same unease while passing through the area even then. This felt like somewhere I wasn't welcome and just shouldn't be, and so I turned east at the first opportunity, tramping more contentedly along the bank of the brook as it formed the boundary of Albany Park. The water bloomed with algae and moved slowly between reedy edges, but despite its deep and straight channel, it felt unusually natural and timeless amid surroundings which shimmered with opportunism and immediacy. The brush-dry parkland looked like a recently mown hay meadow and was speckled with families lounging on the stubble in the intense sunshine which had settled over London for the day it seemed.

At the edge of the park, the path rose to cross Mollison Avenue - the industrial spinal route between outer London and the warehouses and distribution parks which scatter along the eastern edge of Edmonton. This crescent of modern, swiftly-built plastic sheds shows as a bright white mass on aerial photography, like a concerning presence on a body scan. The road was a little over-enthusiastically named for Captain Jim Mollison, early aviator and sometime husband of Amy Johnson - ostensibly due to the presence of the long-serving Weston Aerospace works nearby in Enfield. Below the bridge, hidden deep within a clump of well-established trees, the Small River Lea joined the Turkey Brook. The little river trailed away north, towards Waltham Cross where I'd first crossed this waterway some time back. This boundary crossing also confirmed my passage into the Lea Valley, and with a line of pylons walking south towards the Thames and the bulky chimney of Enfield Power Station towering over the view, it felt strangely comfortable to return to this familiar, semi-urban landscape. Ahead of me the hills of Essex reared up, woodland spreading down from their crests. From here it felt like utter folly to attempt to climb them in the heat of the afternoon. The terrain wasn't helping - offering teasing names like Enfield Wash and Freezy Water to remind me how hot it was trudging through the parched landscape. But this was a place dominated by water and the floor of the valley was noticeably cooler. I parted company with the Turkey Brook here, letting it slip away to the south, through the Prince of Wales Open Space towards the River Lea. It was possible to walk a little further along it, but I'd decided to press on eastwards towards Enfield Lock on the Lee Navigation. A lock has existed here since 1725, with the buildings scattered around it dating from various periods of reconstruction. The Lee Conservancy Toll Office, an attractive cruciform cottage near the lock, is one of the oldest remnants, dating from 1889. Lock 13 sits on a quiet, straight stretch of the Navigation which forms something of a boundary between the redeveloped industrial zones of the western valley and the more rural eastern banks. In the midst of this, clustered around the lock are the much-gentrified remains of the Royal Small Arms Factory. Established in 1816, the site provided greater capacity for delivering ordnance than the previous site at Lewisham in a mill originally used to make armour in the 14th century. The modern buildings at Enfield were not a swift success, fighting closure at several points until the Crimean War brought an arms-making boom in 1853. The site modernised rapidly, adopting mass-production techniques from the USA, and installing steam power to replace the waterwheels which had previously driven the machines. Nevertheless, the tiny pattern of streets which had developed around the factory did not extend far outside the island site bounded by the various channels of the Lea, and generations of families tended to remain within both the village and the employment of the factory. The works continued to thrive through the early part of the 20th century, but entered a decline after the Second World War, partially closing in 1966 and finally shutting its gates in 1988 after a series of privatisations and sales. In some ways little has changed: the mid-century terraces of Ordnance Road face the older factory worker's housing on Government Row across the Navigation - but beyond this, the island is a modern development on private land. There are few ways in or out, and the area has the air of a gated community. I crossed the head of the lock and turned south onto the scrubby path which ran alongside the canal, soon turning aside to circuit Swan and Pike Pool. I picked my way through the depressing mass of litter to a bench I'd rested at on a previous walk and took the opportunity to re-apply sunscreen and greedily drink water before continuing. The pond was quiet and still with a vague waft of refuse drifting in from the incinerator nearby. It was oddly reassuring to be back in the Lea Valley once again, despite its evident drawbacks.

I crossed one of the tangled branches of the Lea which splay around the island, and then the river's main channel by way of impressive concrete footbridges which stood incongruously in otherwise empty fields. Since I'd passed the entrance road to the King George V reservoir, civilisation had made a point of retreating suddenly in the way it often does in these parts. I picked my way along a rough but pleasantly crunching towpath with tall grass waving beside me and only the occasional furiously cycling local skittering by. The path turned north and then east, fringed by impressively tall thistles and extensive crops of nettles. This was Sewardstone Marsh and new territory for me. I'd walked on the western side of the vast reservoir on previous treks, sticking with the line of the Lea Navigation. The eastern bank was wilder and stranger - unmistakably Essex now. My path turned into a rough, broken driveway serving various dilapidated industrial yards which appeared to specialise in disposing of the evidence of motor accidents. If in doubt, it was burned - as too was the large yellow County of Essex signpost nearby advising against fly-tipping. There was a phantom-smell of fire and smoke in the air, a little disconcerting given the furious heat and the dry land. I reached a junction with Sewardstone Road - a thoroughfare I'd considered walking before but which had seemed oddly remote despite being sandwiched between suburban Waltham Cross and Chingford. The road had the feel of a country lane, with a huge farm building converted to a gastropub and many of the old market garden premises now large, rather ostentatious luxury dwellings with gateways capped with stone eagles and drives haphazardly populated by BMWs and Range Rovers. The shimmer of heat and the lack of any other pedestrians made the road feel lawless and dangerous. Cars flashed past at illegal speeds on the long, straight flat valley floor heading for disreputable Car Boot Sales and perhaps a Carvery afterwards? I battled the stereotypes but couldn't quite push them aside, so I decided to follow the London Loop markers once again, striking out over a stile and across a field of tall grass, leaving the road behind me. A well-walked lighter strip of grass indicated the route of the path, though I didn't feel entirely comfortable until I'd passed the first hedge and found myself on a more established track. This land felt contested and defended, though by who I couldn't imagine. It felt like there was no-one outside the confines of a car's cockpit for miles. The path climbed, slowly at first, then more steeply as it zig-zagged towards the summit of Barn Hill and the promise of welcoming tree cover at last. Near the summit, the path dived off into a thicket of trees and over more stiles, emerging at the top of a field where it seemed to duck into the beginnings of Epping Forest. A pair of donkeys sputtered and brayed in the next field. As I crossed the field I was startled by a young, female voice: "Someone's coming! Help. Do you know where we are?". As I approached the trees a small ground of Girl Scouts emerged, maps in hand and compasses dangling around their necks. One of them took the lead in talking to this strange man who'd emerged from the woods: "Are we here?" she enquired politely, pointing to the laminated offcut of Ordnance Survey map they were carrying. "No", I replied, "You're here" - indicating a point on the red dashed arrow they'd clearly been trying and largely succeeding, to follow. They seemed bewildered that the path wasn't marked on the ground - especially where it crashed into the rough, confusing wooded edge of this field - but reassured that they hadn't strayed as far as they feared from the route. I showed them my GPS marker on my 'phone screen and described how the route ahead led to a proper path. After asking about the Ordnance Survey app and a final nervous query about whether the donkeys were loose, they happily trotted off across the grass while I ungracefully flipped myself over the stile and into the confusing wooded patch where they'd come to grief. At this point, I remembered a friend's remark that if I passed nearby today he'd wave from Gilwell Hill where thousands of international Scouts were amassing for a 24-hour event. I figured these weren't the last Scouts I'd see today.

I emerged on Daws Hill with a decision to make - the narrow road ahead lead downhill to Chingford, but meant walking the margin of a busy, fast-running and poorly-sighted lane. I decided instead that the physical effort of tramping across two further hills was preferable to a tense roadside walk, and set off into the driveway of Gillwell Park, the headquarters of Scouting in the UK. As I approached the site, the noise grew from a dull rumble to a full-throated roar. Thousands of teenagers were here - cycling, trekking, camping, singing - it was like a massive theme park based around the wholesome fun I'd read about in Enid Blyton books but never quite found a way to enjoy myself. Happy groups of tanned, healthy young people drifted by speaking a variety of languages and were always faultlessly polite. I spied a veteran scout ahead occupying a deckchair guardpost and made directly for him to check I could pass through to use the footpath. Given that I was a large, sweating, red-faced older man attempting to pass the gates of a campground full of teenagers, he was surprisingly accommodating. He eyed me as I walked towards him and clearly recognised I'd walked quite a way to get here. After a quick chat he indicated where I needed to head to take the path which skirted the site and ascended to the top of Yardley Hill. A little before the summit an unofficial path struck out into an open field. Instinctively, I passed through and headed across the grass, admiring some impressive kite flying which was taking place nearby. As I turned west to find my path onwards, the view of the valley below took my breath away. The silver mirrors of the chain of reservoirs snaked southwards, leading towards a distant city of towers and shadows. Beyond the water the land rose, a green bluff indicating the higher ground where I'd set out this morning. London spread across the edge of valley, not seeming quite so impossibly large or endless here: the tower blocks of Edmonton were tiny upended bricks, and the mass of warehouses and retail shacks along the valley floor looked like an unpainted architect's model. It was impossible not to be moved by the sight of the vast metropolis - and I thought back to circling above the same area yesterday as my flight from Düsseldorf waiting for its appointed slot at Heathrow. The same territory viewed from a different perspective. Then, like now it all felt like it made sense and fitted together. I realised that, despite years of protesting otherwise as I plodded pavements and shadowed streams, I'd begun to know parts of this messy tangle better than I imagined possible. But there was still so much to discover... I made my way down from the hill and immediately climbed again, heading towards the top of Pole Hill. The view wouldn't be great with the trees fully in leaf, and with my knee protesting at being forced into another painful ascent and the air somehow denser and hotter than ever here in the forest, it felt ill-advised - but this seemed like a time to honour tradition. When I finally found my way to the top of the hill, confused by approaching from a new angle, I paused to admire the hazy view over London once again. When I'd first come here it felt like a frontier passed - the edge of a vast forest which must surely remain out of bounds to the likes of me? Since then I'd tramped the woodland paths, returning here again and again on route elsewhere. I touched the obelisk, observing the Meridian, and headed back downhill via the same path beside the golf course which had brought me to Pole Hill on my first visit. At the end of the path, Chingford suddenly began, the forest breaking against it like a wave on the shore. The streets were oddly quiet around the station, a pensive and strange feeling in the air. I felt like I'd descended into a deserted city, and wondered how long I'd been up there in the woods? Then, as I crossed the street to enter the station a loud roar erupted from the bars on the High Street nearby. England had scored. Football, however unlikely it seemed, might just be coming home. I collapsed onto the waiting train and dozed my way back to Liverpool Street. It was probably not wise to attempt this kind of walk on the hottest day of the year so far, and I was feeling the effects. Somehow in the heat the strangeness of Essex was more marked, the stillness of the forest curiously quieter. I was almost relieved when a reveller crossed the concourse of the station sporting a crudely painted Cross of St. George across his red, sunburned cheeks to bark just inches from my face: "IT'S COMING HOME!". Having not spoken for hours and still feeling weirdly disconnected from civilisation I blinked quizzically at him and stayed silent, not sure whether I was expected to agree with him, fight him or run away in terror? He looked at me for long moments, expecting some kind of reaction and getting nothing. Then, meekly and almost thoughtfully he looked down and quietly said to himself "It is. It's coming home..." before scurrying away to yell at his friends some more.

It had been a very unusual day...

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

We are heading out to Germany for a few days to meet friends and see a little of Europe before it gets more complicated to do so. On some of the hottest days of an already warm World Cup summer, travel would present a number of challenges - but today, as ever it seems, French Air Traffic Controllers had decided to strike. The knock-on effects of this were minimal in many ways - a bit of a wait for take-off and a slightly irritated Captain - but there were benefits too... With slots over France in short supply, we took off on the eastern runway, heading directly over Central London and out along the estuary. Even at around 20,000 feet, the view was clear enough to see the city unfolding before me along the glimmering ribbon of the Thames. Seeing the territory I've walked and rewalked mapped out below was a rare and privileged sight for me.

As the contorted city river gave way to the broadening maw of the estuary I thought of the connection between the Thames and the Rhine, once a great river through a united continent which was soon to be artificially separated once again. Beneath me the Dartford Crossing signalled a passing into Kent, and soon the tiny towers of Reculver could be seen below. Beyond this, a sweep of blue showed the channels which boats eager sought between the off-shore wind farms and the ominous heads of the forts at Shivering Sands. Soon there was nothing but water, and then almost imperceptibly the countryside below was Belgium. It didn't look so hugely different from up here, but culturally and politically it could be a world away just now.

Risings on the Commons: A walk in the South Eastern quarter

Posted in London on Saturday 2nd June 2018 at 10:06pm

A sweaty clamber up from Honor Oak Park brought me to the top of One Tree Hill, and as the curtain of summer foliage parted Central London unravelled before me. Since the beginning of the ascent from the roadside near St. Augustine's Church I'd been mostly alone - with just glimpses of dog walkers through the trees - and I was glad. Already drenched and with eyes streaming with allergen-sponsored tears, I felt like a mess - and certainly not suitable for public viewing. The tree-framed window through which London was visible swayed hazily at its edges - perhaps the view would have been more expansive in Autumn, but for now I was content to look on a shimmering city of cranes and towers which rose in the middle distance. London abstracted - no visible sign of the chimerism of inequality or the growing concern about violent crime amongst young people which seemed to be the dominant narrative now. This was an unreal city which, from these southern slopes at least, appeared to be a painted backdrop. I'd meant to come to One Tree Hill for a long time - intrigued by the name, and directed here again by a recent episode of the excellent London's Peaks podcast, I'd finally found the route to fit the urge. My recent walks had occupied me in the south-eastern corner of London, which while something of a diversion, was not unprecedented. This fringe territory where endless suburbs blur into the edges of provincial, unreconstructed Kent had interested me for a long time and the views east from the Thames foreshore were always a draw. So, I'd scored a hasty and uneven line roughly north-easterly along the map - connecting One Tree Hill with my recent travels and roughly approximating the tangled and somewhat unloved Green Chain through South London. The day stretched ahead of me, sweaty and pollen-flecked. It was time to set off...

Before I left One Tree Hill I wandered the top of this significant peak, circling the concrete base of a First World War gun emplacement which sat at the summit to counter zeppelin raids. Sometimes more prosaically known as Honor Oak Hill, the hilltop has been strategically significant for some time, with an East India Company semaphore station established here in the eighteenth century, and the provision of a warning beacon during the Napoleonic Wars. The single tree after which it is named is known as the Honor Oak - where legend has it that Queen Elizabeth rested on her journey to Lewisham, and for centuries a marker of the southern extent of the Honour of Gloucester. This vast feudal estate comprised 279 manors by 1166 when the tree would have been situated in the midst of the still impressive extent of the Great North Wood. The hill later passed to the ownership of the Abbots of Bermondsey before the Dissolution of the Monasteries put paid to their tenure too. The slopes then took on a largely unremarkable existence, with little attention paid to their frequent but informal recreational use until 1896 when the local golf club attempted to enclose the land with a six-foot high fence to deter the locals. The formation of the Honor Hill Protest Committee - including numerous local dignitaries - soon followed, with the aim of protecting the public right of way to walk on the hill. The interminable administrative process of dealing with numerous landowners and vestries threatened to drag on for far too long for a number of local folk who on 10th October 1897 broke down the fence and stormed the hill. A reported crowd of 15,000 dispersed peacefully after singing 'Rule Britannia' at the summit. A week later with ranks swelled to over 50,000 the mob was more unruly, with stone-throwing and fire-setting taking place. Ten were arrested for trespass and fined or imprisoned which appeared to successfully quell these guerilla tactics. However, the protest continued through more ponderous legal channels, not finally being resolved until 1905 when the recently formed Borough of Camberwell purchased the land. The view - once claimed by Sir John Betjeman to be "As a prospect [...] better than that from Parliament Hill on Hampstead Heath" remains impressive - and with this last outcrop of the range of hills which climb steadily from Croydon being visible from some distance, it is no suprise that it has attracted a mythology - from Boudicca's last defeat to Dick Turpin's look-out.

I skirted the foot of the hill via the woodland path which wound between the trees, shadowing Brenchley Gardens. This broad, curving road sat on the embankment of the former railway branchline to Crystal Palace which I'd encountered previously on the South Circular. Beyond the railway alignment in in an unlikely symbiosis, the vast underground Honor Oak reservoir was covered by the well-kept greens of the Aquarius Golf Club. Glimpses of the view across the Thames filtered between the buildings as I followed the road to the gates of Camberwell New Cemetery. I passed the through imposing white-painted gateway and walked the ceremonial route towards the Mortuary Chapel - a rather traditional ecclesiastical-looking building by Sir Aston Webb and his son, Maurice which opened with the cemetery in 1927. A path took me towards the more impressive Crematorium by Maurice Webb working alone which was built in 1939 in a modern style with a fine square tower and stained glass window. While the bereaved rolled up to refresh flowers and tend graves, it felt strange and perhaps wrong to photograph this building, but there was a curious life and buzz about the place which prevented it becoming entirely macabre, assisted by the fact that the paths of the cemetery were surprisingly well used by those heading for the nearby recreation ground in football colours for a junior match of some apparent importance. This corner of London - not quite Forest Hill, not quite Peckham - is a strange city of the dead with the former boroughs of Camberwell and Lewisham both locating their respective Necropolis on the line dividing their turf. The tracks of the railway lines to Brighton parallel the old administrative boundary, occupying the former route of the ill-fated Croydon Canal, and I crossed their deep cutting via a slightly forbidding footbridge and entered the often overlooked village centre of Crofton Park. This suburb on the site of the original hamlet of Brockley largely exists only because of its own small and somewhat unloved station on the lines into Blackfriars. Near the station, the Rivoli Ballroom stands resolute - the last extant example of the opulent and somewhat kitsch dancehalls which would have graced almost every suburban High Road in the mid 20th century. My route continued east via the long curving route of Brockley Grove, a pleasant street of decent houses which faced the tall, swaying uncut grass of Brockley and Ladywell Cemetery. Formerly separated by a wall, these two burial grounds opened within a month of each other in 1858 as Deptford and Lewisham Cemeteries respectively, and didn't finally become a single cemetery until 1948. Given their proximity to the Naval Yards of Depford, both feature a number of nautical burials, not least that of William Rivers who was killed by 'falling from the maintop of HMS Sapphire at Hobart Town on November 5th 1877 aged 19'. Now the wall separating the two sites had fallen, and both had returned to nature to a great extent - but at the Ladywell end a rather grand iron gate still worked hard to outshine its neighbour.

Stately Brockley Grove dissolved into Ladywell Road and once again I crossed one of the imperceptible lines which divide South London communities. The road began a gradual descent into the valley of the Ravensbourne via a ladder of terraced streets leading south, all given clumsy-sounding compound names to honour the Victorian builder's sizeable flock of children: Elsiemaud, Amyruth, Arthurdon and so on passed by as I trudged towards the much-gentrified centre of Ladywell. I quickly recognised the pleasant little village around the railway station from a previous walk, but I hadn't noted during that riparian approach just how jarring the transition was from a proud but struggling mainly black neighbourhood into the resolutely white hipster-magnets of the bakeries and taverns which clustered around the bridge. Beneath the road, the River Ravensbourne gurgled in its concrete prison while the heat which was now beating down on the tarmac made the cool flow of even this beleaguered watercourse seem oddly attractive. I moved onward, descending from the bridge and soon leaving Ladywell to enter the hinterlands of Lewisham. I hadn't originally intended to head this way - my plans suggested a route further to the south, even perhaps rewinding part of my perambulation around the South Circular - which felt less than edifying today. But the need to find a drink had driven me towards civilisation which was perhaps no bad thing. The route also led me past the remarkable Ladywell Bathhouse. More lately known as the 'Playtower' this remarkable survival of a 19th century swimming pool and bathing facility is part of a cluster of former civic buildings beside the Police Station and Mortuary buidlings. Erected in 1884, and designed in part by the local architect Thomas Aldwinkle, the building was remarked on by the Kentish Mercury as 'quite an ornament to the neighbourhood, standing in striking contrast to the ancient church behind it. The building has a remarkable local history - having hosted record-breaking swimming champions, political meetings, Olympic standard gymnasts and finally a play centre until final closure in 2004. Since then the building has decayed and suffered arson attacks - to the extent that it was named one of the ten most at risk buildings by the Victorian Society in 2015. Boarded up and abandoned, the building awaits its fate - which more optimistically appears to be conversion to a Curzon cinema sometime soon.

After the rather quiet civic island on the outskirts of town, the sudden rush of Lewisham High Street was something of a shock. Traffic pulsed through the lights, and I tried to plan my next move while navigating the busy pavement. People stood around outside shops as if stunned by the sudden heat, and I slalomed around them in an attempt to find somewhere to stock up on liquids before taking on the steeper hills later in the walk. My initial plan of dashing across the street and back into the suburbs was soon abandoned - this stretch of High Street had little to offer and I was forced to head for the centre of town. The skyline was a broad frieze of blue sky and tall cranes - the same knot of new buildings I'd seen from the river on an earlier visit. Close up the new developments were uninspiring and formulaic: stacked geometries of primary colours and too-clever angles. Names were to be assumed by interpretation from some ancient use of the ground on which these new buildings sprouted, resulting in a proliferation of granaries, mills, stables and the like. A little way to the north, the High Street divided around the gloomy brick stacks of the former Riverdale Centre. Dating from 1977 this surprisingly large shopping centre is due for an upgrade soon, and in some ways is remarkable in retaining considerable footfall despite new developments nearby which have effectively killed-off similar centres around the capital. That said, the offer here was in the mid-to-lower sector of the market which was echoed in the drab facades of the clearly struggling High Street which glowered across at the centre. Between the run of bus stands and the stores, a steel band belted out music to a heat-subdued crowd which nodded and shuddered lazily to the irrepressible clamour. I swerved onward, finding myself at the unprepossessing corner of Lee High Street. A wall of buses waited to turn the corner, and I wondered if I'd made the right choice of walk today. The sun had dipped behind low cloud and the air had become a sticky, fume-laden soup which coated the inside of my dry mouth unpleasantly. I withdrew cash but couldn't find anywhere to spend it - Lewisham had almost defeated me. It remained an overheated and frustrating mystery - and just as confusing and unwelcoming as it had felt on my previous brief passes through the territory. Perversely, I wanted to understand the place even more as a result. The road ahead - the A20 - which was still somewhat anachronistically signposed 'Channel Tunnel' swiftly became a typical London escape-route which could be at any corner of the compass with the ubiquitous ranks of hair salons and kebab shops tumbling along both sides. Preparing for a dull stretch of walking, I glanced along the oblique junction with Clarendon Rise and was stunned out of my mental grumbling. Firstly, a beautiful Hindu temple stood rather surprising among the garages and back-entrances, set a little back from the road and in a tight, corner site. The decorative plaster front dripped with carvings and reliefs, the gable divided by an impressive stacked tower which glinted above its drab surroundings. At ground level beside the temple a faded blue railing signified water. I've come to know these tell-tale gaps in the streetscape well and always investigate them for potential brooks and streams. Sure enough, trickling grimily below the road the Quaggy River snaked out from under Lewisham and headed east. This gave my walk something of a new energy - and I struck out with a little more effort than I'd managed on the last stretch.

The Quaggy soon slipped out of site. Forming the boundary of back gardens and mediated by flood relief schemes, it is an anonymous river for much of its course. My own first encounter was years ago at Lewisham Station where it passed below the platform in an unremarkable concrete culvert helpfully accompanied by an Olympic-funded information board. Here though it was still cocooned, but it felt wilder and intruded somewhat more on its surroundings. The land dipped towards its shallow valley, and the street patterns followed its torturous curves. The Quaggy was still making its mark it seemed. I pressed on via road, following the straighter route while the river looped lazily to the south. I could have deviated away from the road and headed for Manor Park, but I was confident I had the river in my sights again. Sure enough, as I poked around the outskirts of the Sainsbury's at Lee, the river again appeared passing under a nondescript bridge nearby. Its neighbours had built a platform to sit above the waters beside their business, and it was hard to tell if this was a slight on the apparent unimportance of the river or a genuine attempt to make the most of otherwise urban surroundings. Once I finally found my way into the store, I shopped swiftly and considered my options - I could try to approximate the route of the Quaggy, ending up at the South Circular a little further away than I'd hoped - or I could use it as a loose guide and strike out into the uncharted private avenues of the Cator Estate? I opted for the latter, disappearing into the leafy and primped Manor Way and soon feeling unpleasantly oppressed by the experience. Once past the gates and the rather disapproving glare of the red-brick gatehouses the road was straight and dull, lined on one side by ranks of pleasant and expensive looking homes while to the south the land fell away to become Blackheath Park on the banks of the Quaggy. Much of my walk through the estate of John Cator (who's other lands I'd encountered before) was spent worrying about finding an exit or being turned back to the start by an overeager security guard. In the event, the exit showed up first - after passing a little extension to the estate posed around an ornamental lake formed from what appeared to be the sometimes elusive Mid Kid Brook stream, a grim access path led away behind a block of untidy garages next to the less salubrious homes of Casterbridge Road. Here I noticed a phenomenon which had seemed at first unlikely but for which evidence was now harder to ignore: the endless parade of 'Saturday dads' walking or wheeling their children along the quiet afternoon roads. Across Lewisham and Ladywell I'd seen the same parade - a faintly depressing sense of resignation on the faces of the pushchair driving men while their offspring chattered excitedly or dozed in the heat. I sensed the frustration and defeat of many of them, among sometimes more hopeful scenes. Aware of my perhaps unfair assumptions, I took my spot in this parade and slalomed along a much-diverted path through a development zone bounded by view-defying temporary wooden fences covered in computer-generated scenes of urban paradise. I need not have worried about finding a way out - the proprietors of Kidbrooke Village really seemed to want me to head this way and to see all of their promotional material...

And so I found myself in one of the most uncanny zones of London I've experienced since those heady pre-2012 days in Stratford. Put simply, Kidbrooke Village didn't exist, despite the best efforts of Berkeley Homes to convince me it was here. This was the site of the Ferrier Estate. Constructed between 1967 and 1972 by the Greater London Council, when completed the estate consisted of nearly 2000 homes in eleven 12-storey prefabricated blocks and associated low-rise units linked by walkways. Perched on the edge of resolutely White British Greenwich the estate didn't fare well and became a convenient spot to manage demand for social accommodation by the flawed strategy of housing many families who were on the margins of the Borough's population on the same estates. A combination of sharply increased numbers of refugee families, a dizzying mix of languages and ethnicities and a policy of generally abandoning maintenance and improvements meant the fate of the estate was sealed. It was often mentioned in the same breath as the other two inconveniently troublesome South London 'hell holes': Heygate, Aylesbury, Ferrier. Only total erasure would exorcise these failures of policy - at least in the minds of those who had, in some cases presided over their construction. And so they fell, and thus by 2012 much of the old estate had gone and Kidbrooke Village had moved from a hazy, watercolour sketch on a drawing board to a concrete plan. Meanwhile the Ferrier residents were being scattered around the capital and beyond. Berkeley were going to do this differently, however - they'd build a community, not just houses. And so in the midst of the landscaped wetlands which may or may not be fed by the vestigial waters of the Kyd Brook, the 'Village Centre' squatted the corner of a modern block. Looking worryingly temporary in nature, the doors were closed today. Few people were around, and while I unenthusiastically downed an unripe banana, only a few more dads and a powered-wheelchair passed by. I located a waste bin - pristine and empty of course - and headed east towards the station. The parcel of vacant land between the railway and the village was being slowly filled in - a new academy and more housing were promised on the glossy hoardings surrounding the plot - and the road onward was lined with scaffolded blocks awaiting their final fit-out. It struck me here that Kidbrooke was no more - the station served the new village, but any sense of a historical Kidbrooke had been erased. The suburban hinterlands stretched away north - but the place had been bypassed twice already, and the focus had shifted south. I navigated the pedestrian subways under the confusing junction where the improved route of the A2 bucked and reared northwards towards London noting there was no indication of how far away Kidbrooke was on foot among the direction signs. In fact, this spot in the underpass may as well have been the real village centre - and indeed perhaps once was?

The footpath emerged from its cool, green tunnel at Kidbrooke Green Park. This parched lozenge of parkland bounded by the old and new routes of the A2 was scattered with sunbathers and dog walkers who didn't appear to regard their local bit of respite from the suburbs as a historically important scrap of ancient wetland at all. This remaining corner of the former village green is evidence of a set of historical compromises which could have led to a very different landscape hereabouts. Kidbrooke as a suburb is a recent development, having largely grown up along the route of Rochester Way - a bypass for Shooter's Hill which offered traffic a flatter, less taxing route out of London from the 1930s, slicing into the green in the process. The remains of the village green were then later proposed as the location of a vast interchange between the southern and eastern flanks of The C Ringway - the urban motorway which was to have connected the North Circular to a replacement for the South Circular. This road would then have turned east and scythed an utterly destructive course through South London's suburbs on a viaduct. Little of this road was built, but evidence of the extent of its impact can be seen in the strips of new development which fill in the once reserved motorway corridors which languished while the plan was debated by the GLC and the Boroughs. The complex twist in the A2 here also gives a clue as to how much would have been entirely obliterated by the South Cross Route as it ploughed west towards Brixton and Camberwell. The plans were not popular with the London Boroughs, and in particular were fought bitterly by Eltham and Greenwich, and despite a number of proposed concessions they were finally buried with the remains of the inner Ringway plans by 1973. The people of Kidbrooke likely have the residents of Blackheath to thank for this, as the organised opposition to the devastating destruction of shops and homes in their village forced consideration of a cut-and-cover tunnel which delayed construction and escalated costs to unsustainable levels. There may not be much of Kidbrooke's Village Green to see now - but there could have been far, far less. It was becoming extremely hot walking weather now - and I clocked the temperature at approaching thirty degrees as I crossed the yellowing grass of the park and emerged on Rochester Way. The long straight carriageway shimmered in the heat between its generous pavements and wide verges. This was classic London arterial: a textbook example of how roads into and out of town were envisaged in the earliest days of the motor age. I set off, fixing my eyes on the wooded slopes rising in the near distance. I was keen to get back under the trees and to shelter from the overbearing sunlight as soon as I could. The ribbon of tarmac unravelled endlessly ahead - a modern-day Watling Street on which surprisingly little traffic bothered my ears. A bypass that had been bypassed already, its lifespan as a major route ended by the wider and louder A2 which was still within earshot to the south, offering a thrum of white noise to the still and hazy afternoon heat.

A diversion into the quiet side streets had given me an initial hint of how steep the ascent would be from this direction, but I wasn't fully prepared for the slope which rose between houses to climb a meadow and disappear into the trees. Shooters' Hill had been a challenge last time, but approaching from the south the ascent was steeper and less forgiving. I fixed on a bench halfway up the rise towards the crest and leant into the climb. As I approached I noticed that a family had set up their picnic under the trees opposite the bench, and my British reserve wouldn't allow me to collapse sweating and panting just feet from their chosen spot. So I pushed on, suppressing my heavy breathing enough to pant a hopefully nonchalant and breezily casual 'Afternoon!' as I trudged by. At the top of the hill I found a fallen tree I'd been aiming for had just been alighted on by a cackling and capering gang of exchange students with lurid backpacks and packed lunches, so I leaned against the cool trunk of a venerable tree and rested, surveying the panorama of South London which was revealed from this height. The view southwards often feels less impressively sweeping - perhaps because the hillier terrain of the south doesn't permit the same vast panoramas seen toward the north. It struck me however, under the canopy of ancient woodland here, that there would once have been a sea of treetops as far as I could see - the Great North Wood stretching south into a hazy green distance. I turned back to the climb, wanting to find my way deeper into Oxleas Woods. The footpaths were busy with families, a distinct aroma of sunblock and ice cream preventing me from feeling like I was truly treading ancient byways here. Nevertheless, the woodland paths felt surprisingly wild in places and I was able to head deeper and lose myself in the greenery. The mossy trunks and ceiling of foliage tinted the view green, and kept me pleasantly cool while the path crunched with fallen twigs and seed pods. I slowed my pace to enjoy the cool respite offered by this venerable swathe of woodland. In the process I managed to regain both composure and a reasonable core temperature, at least until I emerged in the remnants of formal gardens which had belonged to one of the large properties which once flanked the woodland where the sun beat down on me once again. The water tower at the top of Shooter's Hill dominated the view - and I soon found myself near The Bell once again, waiting to cross the busy flow of traffic and looking back over the scene of my recent walk in from Kent. My aim now was to further retrace that route, at least as far as the Shrewsbury Tumulus. I wanted to take the mysterious route of Mayplace Lane down the hill towards the Thames. Sure enough, the curious little track was waiting beside the swaying grass on the burial mound, just as it had apparently waited for time immemorial. My oldest maps of the area show the lane bending to the north and slightly east, resolutely retaining its route as generations of new development slowly surrounded it. The street signs suggested the route was not suitable for vehicles - and in fact it appeared it was also not ideal for my aching left knee which clicked and popped ominously as I began the descent on the winding lane which provided a rutted and uneven service road at the rear of properties on Eglinton Hill. I marvelled at the driving skills of residents who apparently managed to get their cars along this track and into the various garages and gardens which backed onto the route. The lane headed steeper down hill, crossing several roads of Victorian terraces which had remarkably allowed this old route to cross unhindered. I was amazed that the unsentimental and economically-minded builders of that era would have willingly left a house unbuilt on each road to accommodate Mayplace Lane. Eventually the route gave up at the foot of the hill near the shops on Herbert Road. The tall, brick blocks of the somewhat infamous Barnfield Estate loomed over the end of the lane as I made my way between buildings and back to more modern carriageways, glad to have followed Mayplace Lane - but still intrigued to know if it had ever reached all the way to the Thames?

I was now heading east again along Plumstead Common Road, which was surprisingly congested and difficult to cross. My aim was to walk a short distance along the road before getting swiftly off the pavement and onto the Common. As I approached I noticed the grass was busy with sunbathers haphazardly scattered across the generous green area which had, like One Tree Hill been hard-won. The Common has a long history of public use, being mentioned in the Domesday Book as Plumstede - a place where plums grow - even then known as common land used for grazing. As the Royal Arsenal expanded operations at Woolwich, large swathes of the Common were secured from Queens College, Oxford who owned the land, to provide space for workers' homes. The coming of the railways rapidly accelerated this process of building new suburbs, and In June 1876 the local populace began to take action to defend their ancient rights. These protests caught the attention of the Commons Protection League and charismatic and radical Irishman John De Morgan in particular - and on 1st July, under his leadership a crowd of 1000 people stormed the common, tearing up illegal fences and marching on the home of Sir Edwin Hughes, local Member of Parliament and at the time, also leader of the Conservative Party. De Morgan was arrested and jailed for seventeen days, but the increasing pressure on local politicans resulted in the passage of the Plumstead Common Act in 1878 and the purchase by the Metropolitan Board of Works which has resulted in the area remaining protected to this day. Near a rank of well-used tennis courts I paused to rest, watching a mysterious black-clad young woman undertaking some sort of outdoor art-project involving a huge carpet of taped-together paper and spray-cans on the footpath nearby. A little way across the common was the football pitch where Arsenal FC had played their first games, originally as the 'football division' of Dial Square Cricket Club, founded by the workers of Woolwich Arsenal. Much had changed on the common since then, and the tiny café next to the Old Mill public house was now 'The Plumstead Pantry' with a nice line in artisan coffee and exclusive baked goods. As I trudged by, glancing up at the brick tower of the windmill which remained in the grounds of the nearby pub, a young customer pushed by, busily devouring a croissant in a cloud of pastry dust and swaggering across the width of the pavement. He paused to glug greedily at a thimble-sized cup of coffee, so I made my escape- scooting by and getting on my way as swiftly as I could. The Common stretched to the east - an impressive swathe of land had been secured by those protests including a spot intriguingly marked on my map as The Slade Ravine. I followed the path rather skeptically, thinking that something as impressive as a ravine would surely have made it into the mythology of London which I'd been reading for years? The path dipped into a tunnel of trees and became a flight of steep stone steps, and two things became apparent: firstly that there was genuinely a ravine in Plumstead Common, and secondly that I'd likely to have to clamber up the other side of this rather deep impression in the landscape! At the bottom of the ravine a series of ponds separated by weirs and filter beds provided a cool, green-shaded haven for wildlife. This strange, venerable place deep in the earth felt safe and hidden, even from the now overbearing heat and the drone of traffic on Kings Highway nearby. Formed by a glacier melting into a fast-flowing river during the last ice age, The Slade was now a dry gully carved deep into the land, dividing Plumstead Common from Winns Common where a Bronze Age burial mound is all that remains of an established dwelling which endured through Roman times. Winns Common was reinhabited briefly after the Second World War when a village of prefabricated homes housed the Blitzed and displaced folk of London. Generations of settlers would have known this spot, and unlike its surroundings, it would have looked remarkably similar to them too.

I struggled up the steps out of the ravine slowly, noting another walker following me and picking up my cue to take things equally steady despite likely being a good deal fitter than I. I collapsed onto a nearby bench and tried to look nonchalant as I consumed the last of my water and decided what to do next. I think my fellow sweaty and exhausted walker was jealous of my bench, but there were others to be had not far away! My plan had been to tackle Bostall Hill and descend on Abbey Wood via the site of Lesnes Abbey - but that would have to wait. Another ascent in the blazing sunshine was a little too much to contemplate just now. Instead I decided to strike out for the same spot by staying on the flat as far as I could. After crossing Winn's Common I began the descent towards the Thames, my knee now making genuinely ominous noises as I shuffled downhill passing by a series of geologically-themed squat tower blocks: Crystal, Galena and Marble House. All of them were prematurely decked with the St. George Cross in anticipation of a World Cup to come. From this vantage point the floodplain of the Thames opened out impressively below, with the near distance occupied by the Crossrail depot and the curious industrial estate-like anonymity of HMP Belmarsh, home to Britain's most violent and prolific offenders. Flanked by its sister prisons, HMP Isis and HMP Thameside, all three looked like innocuously vast branches of B&Q from this safe distance. At the foot of the hill, Plumstead High Street pulsed with heat and shuddered with car stereo basslines while we all waited time at the junction with Basildon Road. Fumes and dust hovered in the air, and I was glad to reach an opportunity to turn into the side-streets and zig-zag towards Abbey Wood station. My spirits and my feet had rallied now that the end of the walk was in sight, but swiftly fell again when I spied a bus heading my way marked 'Rail Replacement Service'... I may not have needed to plan this walk extensively, but I had - embarrassingly - left some of the key details unchecked it seemed. I swiftly replanned - and noted a regular bus service from outside the currently closed station which made a circuit of Thamesmead before depositing passengers at Plumstead station, the current extent of operations on the line. This local service seemed infinitely preferably to a slog through the same clogged streets I'd just walked on a hot bus full of disgruntled would-be rail passengers. A short wait followed, before a small group of us were whisked away by a single-decker which navigated the intricate web of roads through this vast and relatively late-come suburb of London. As we passed over the Southern Outfall Sewer at Eastern Way I was able to orient myself by way of an earlier walk in similarly hot weather. After observing the other-worldly architecture of the original concrete blocks and walkways of Thamesmead passing by, I settled into my seat for the remainder of the ride, before joining most of the other passengers on a dash around the corner for a waiting train at Plumstead station.

On the run back over the South London rooftops I pondered today's walk. Everything felt strange and temporary just now, uncomfortably close to the brink. My thoughts and indeed dreams were plagued by decisions I had little power over. This was the perfect antidote - a walk to connect points which had become increasingly familiar, but one which didn't have a definite purpose. With no river or road to follow and no fixed itinerary, I'd failed no-one by turning aside here or there: being seduced into tracking parts of the Quaggy River in Lewisham, but abandoning it to explore the lost suburb of Kidbrooke or even my final diversion away from the route in Abbey Wood. Instead, I'd walked off a little of my anxiety, letting it evaporate into the heat as I let the byways of London take me largely where they chose. I thought back to the moment on the top of One Tree Hill, gazing out over London as an unreal, painted city. I thought too about the protestors who had gathered at One Tree Hill and on Plumstead Common to protect my future right to walk on unspoiled greenspaces within London. The backstreets of Lewisham felt more solid and dependable than any panorama just now, and a bit of steadfast reality was just what I'd needed today.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.