UPDATE: You can now buy Adverse Camber on Amazon UK and Amazon USA.

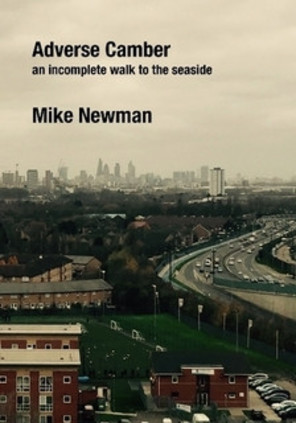

Over the past couple of months, I've revisited the posts I wrote here about the incomplete A13 walk which I took back in 2015/16. They felt a little self-indulgent, but were in places interesting enough that I thought I'd like to do something a little different with them. Since those walks, I've tended to write in a little more detail about the history of places I visit, and it felt like revising them a little in that light might also help. I'd also recently dug out a copy of Remapping High Wycombe by John Rogers, a project he'd self-published a long while back via Lulu.com. Flicking through that fascinating little book, I thought perhaps that this might be a good home for the A13 posts. And so, Adverse Camber was born...

I've never tried anything like this before: on one hand it feels supremely pompous to present what were essentially lengthy field notes in this way, on another it feels like a fitting home for some of the words which were spinning around me at a challenging and complex time in my life. One thing is certain: these walks set a pattern for me which has endured and sustains me to this day. The opportunity to put some of these thoughts alongside some of the images I captured along the way has helped me to reconnect with why I write, where I could improve and how these walks impact on my thoughts.

I don't think this will become a huge seller, particularly given the sometimes pricy shipping costs - but if you've enjoyed the posts here over the years and want to offer some support, this might be an interesting way to help out a little. You can click the button above to get to the store - and the discount code LULU10 at the checkout might help a little too!

It feels important to start where I left off. A month ago I looked out over Rainham Marshes with some trepidation. I'd almost resolved to carry on walking that day - to push on the few more miles to Purfleet. As I stood in much the same spot, I knew I'd never have made it if I'd tried. It was a hazily warm morning, sky like silver and slate, the marsh grass reflecting back none of its colour. I made a guess at the spot where I'd discarded my parents' key and paid a silent tribute. I realised with some dismay that I was now linked to this spot forever. My usual memory raid, in and out of a place before it could properly get under my skin, wouldn't work here. In fairness it hadn't worked much as I'd progressed into the east - and from the dirty chasm of Aldgate to the empty flood plains of Dagenham, I'd connected curiously easily with the terrain despite it being so far from my own experience. It was good to be back out here, contemplating a trudge across the gloomy marshes to the river. As I'd made the journey out from Fenchurch Street I'd doubted my ability to get quite as far as I planned today - I felt distinctly post-viral, a sweaty brow and a chest which fluttered oddly, causing fleeting thoughts of mortality and frequent checks of my heart rate. I brushed them aside with a likely unwise bacon roll washed down with more caffeine and focused on the walk ahead.

The first section of my walk felt true to the spirit and purpose of this unhinged enterprise as I strode out along a narrow strip of paved path between deep marsh grasses towards the A13, marching on elegant but strangely ominous stilts across the wetlands. The wind carried the sound away, and the traffic both looked and felt impossibly far-off, like a Patrick Keiller long shot of the viaduct. The road was just about the only thing providing some sort of form in this unsettling landscape, beyond that the land rose into an entirely artificial hill of accumulated landfill. The detritus of London brought to the fringe of the city to decay - safely distant from rate-paying habitation. I realise that I'm alone. I left the last of the dog walkers loitering suspiciously where the path which leads out to the viaduct parted from the local circuit of pale pink shit-sacks and suspiciously steaming tufts of grass. They stood around, fingers flicking over illuminated 'phone screens without clear purpose. Now there is just me out here. Me and cows. By far my least favourite animal - admirable from afar for their sheer improbability, their huge frames suspended from near-exposed spines while they lumber around a field of sub-standard marsh grass, nosing for the long depleted good stuff. The path headed directly towards the river, running parallel to a range of industrial buildings of uncertain purpose - only the last of them giving away its identity as a manufacturer of pre-cooked rice. The hill of waste was between me and the river, and it wasn't immediately obvious how I'd cross it. I soon found myself on Coldharbour Lane, a branch of the Ferry Lane Industrial Area - the wind-blasted, dusty thoroughfare I'd left at the end of last months' walk. The lane wound its way under the A13 and out to the fringe of the waste facility, before becoming this disconcertingly straight service road. Signs barked prohibition. The footpath was sequestered on the southern edge, a concession to the signposted walking routes which inconveniently bisect the trashlands, making them public when they are built to conceal. There was no traffic to beware of. A gatehouse up ahead seemed inactive, the barrier waving lazily in the wind. Just before the public/private boundary, a turning to my right took me along a rising, curved road which followed the outlet of the watercourse, the rice factory on its other bank. As the road rose, there was something about the flat, white sky which gave away the river's presence. A few more steps and the sweep of the Thames was revealed to me. To my right, the towers of the Isle of Dogs shimmered in the distance, while across the water minor industry struggled on on the fringes of Erith. But I was drawn to the east: the high towers of the elegant Dartford Crossing blinking back as it lurched over the river, the towers of the Proctor and Gamble works - it all looked so impossibly far away just now.

The car park was surprisingly busy: cab sleepers, dog walkers and bird watchers with flasks of steaming tea. Those who were awake looked resolutely out across the river. There was a faint sense of loss about the place. With the impressive expanse of the marshes hidden behind the vast mound of refuse, the path was the only escape. I felt almost guilty for feeling so surprisingly energised by the place. The ribbon of silver river called - this project so far had kept me away from water, my encounters with rivers were fleeting crossings at best. Immediately after I'd slipped through the gate onto the path I encountered a warning about straying into the waste lands. Beyond this, the path curved to navigate an inlet, and scattered within it were the hulks of concrete barges, abandoned unceremoniously after wartime service. The mossy, weed-draped hulls emerged from the inlet at crazy angles: some tipped their prows to the sky, others turned their shell-crusted flanks to the path. The forlorn scene was completed by a sculpture - John Kaufman's "The Diver: Regeneration". A strange wireframe figure, emerging from the mudflats, draped in weed and litter. A tribute to those who have worked the hostile estuarial environments out here, covered in the flotsam which keeps this an officially sanctioned danger zone.

The path hugged the river bank as I turned east again, and faced the estuary. The path was, predictably deserted here. Sandwiched between the silted fringe of the river and the fence of the waste facility, my walk was almost a textbook edgeland excursion. On one had I had the silver sheet of the Thames and the curious riparian foliage, on the other a dusty extension of Coldharbour Lane which thundered with heavy tractor units. WIthout their trailing loads, the cabs leered oddly forwards, imbalanced and purposeful, as they hammered around the corner and onto the edge of the plant. One thing both river and land had in common was rubbish. The wind-tossed overtoppings from the plant strung itself through the dried weedstems. Tucked between two tufts of grey-yellow grass I spied a fading nautical chart of the Thames, just out of my reach. An experimental energy generation plant belched out dark, organic sludge beside the road and generated the most curious smell: a sort of sweet, greasy earth, tinged with decay. After crossing a jetty serving the refuse station, I rounded Coldharbour Point and got a view of the territory ahead. Traffic on the bridge flickered in the middle distance, while across the river the waterfront of Erith dominated the view - a collection of modern apartments mimicking the traditional cliff of stucco-covered seafront buildings. Here I turned briefly inland, navigating the path as it climbed around the eastern edge of the waste mound. Rainham Marshes stretched before me - the A13 and High Speed 1 grazing the edge of the vision on low viaducts, which alternately rose and fell to cross each other just out of shot. Beyond the road, the village of Wennington and a smudge of red which signified the brick buildings of Purfleet. Between me and the distance? Nothing. An expanse of wet scrubland, marsh grass, ditches cut deep into the soil. Occasional human trappings were becoming integrated - rifle targets slowly discolouring to match the earth, bird-watching hides gradually becoming hidden themselves. The view from the slight elevation of the bund which protects the marsh was oddly spectacular and affecting. Looking back across the river, the flat and open foreshore was equally evident, emphasising the height of Dartford Creek Barrier which towered over the mouth of the River Darrent where it emptied into the Thames.

I spent quite a while chatting and lingering in the RSPB centre on the edge of the marsh, a curious half-glass camouflage block which couples a tea room and public facilities with a relatively luxurious hide for the discerning twitcher. The coffee was passable and the locals were interesting, if not terribly well informed about the river path. After being passed among a number of them, they proved knowledgeable enough about the route back towards London but they remained remarkably hazy on the eastward path. They knew I could get into Purfleet, but after that? Who knows. And to Southend! Why? It occurred to me here that they had me down as a more traditional kind of walker than perhaps I really am, and that they'd have seen landfill or a reeking soapworks as a barrier to passage. Not so far me of course, so I'd have to trust my nose. I left the impressive centre and set off over the bridge into Purfleet, passing the historic village green and the Powder Magazine - a survival from 1759. The river path dwindled to an access-only route to the inevitable stacks of river-front apartments, so I turned inland and found myself walking a surprisingly busy road through the bleak remains of the town. My first call was St. Stephen's Church - a long, low and fairly modern building which served as a chapel and church hall for the long-demolished Purfleet House. The assumed history here though is entirely myth - this was likely the model for Carfax, the house scouted by Jonathan Harker for Count Dracula. It seems a forlorn enough spot - but that has more to do with Purfleet's down-at-heel aspect than any supernatural force. Near the level crossing a single corner shop was open, its bored owner reading the classified ads at the back of a local paper with impressive focus. Anything to make time pass just a little faster out here. I bought water and chocolate and set off again. The station was oddly inviting - a near immediate escape from this odd little place which seemed to be almost entirely asleep on a Saturday afternoon. A bus sputtered by, picking up speed after a stop on route to Lakeside, the windows misted. Full of eager shoppers being drawn into the retail epicentre. I crossed the street, hedging my bets on which pavement would fail me first, and headed out of town. The road leading away from Purfleet is nestled at the foot of a chalky cliff, with new housing developments stacked against it and rising to meet it. Between the road and the river is a widening band of industrial land - including the vast oil terminal I was passing, realising I had a family link of sorts with the area. I didn't stop to investigate - navigating the cars parked on pavements, and choosing the right moment to slalom around them, avoiding the oncoming stream of tankers was something of a preoccupation. As I left the built-up area behind, I spotted the unlikely bulk of the Royal Opera House production facility in a large hangar behind a development of neat, new housing. It was incongruous and strange, but perhaps no more so than the continued existence of places like Purfleet at all. These edgeland towns which have been reduced to near hamlet status by virtue of the gravitational pull of nearby out-of-town developments seem improbable at best, and likely unsustainable. I wouldn't be surprised if I came back to find I'd dreamed Purfleet, written it forward from fiction and believed my own overcooked prose.

The official exit to Purfleet appears to be the strange dog-leg junction with the A1090. Suddenly, the environment is full of stimuli which have been absent in the village. The sky opens. The slender towers of the QEII bridge loom suddenly large, the oversized pylons carrying power cables across the estuary nestled behind them. HS1 crosses the road too, plotting its course to head under the river not far from here. Trains don't so much rattle as blast by, leaving a dusty gust of air in their wake. I take the exit for Thurrock here, feeling suddenly a long way from where I set out in the cool green calm of the marshes, but equally far from my goal. I'm almost disheartened here as I walk through rough scrubland, with a curtain of trees between the road and the plain of warehouses and refineries. But the bridge is upon me now: towering ominously above my route, a lattice of road and railway rising and plunging across the road. Passing underneath is unremarkable, and pushes me unpleasantly close to the thundering fuel tankers. I can feel the motorway above more than I can hear it. I feel my jawbone vibrating, my teeth touching in rhythm with the traffic above. The air is gritty with dust thrown up from the road, and cast down from the bridge - I feel it crunching between my teeth. The red ensign of the Ibis Hotel forms through the haze. I realise I've crossed another margin here: I'm outside the M25 now. London is definitely behind me, a punctured balloon which I'm escaping from in slow motion. This is a parody of the greenbelt - a rustbelt, industry not economically tolerated within the ring of concrete slowly decays here. Even the Waste Transfer Station had more purpose, more cachet than some of the cut-price tyre merchants here. Passing the Ibis is payment of homage to an unlikely literary landmark: much of the action of Iain Sinclair's "Dining On Stones" focuses on the hotel. It is a watchtower above the road, a proxy for the sublime tracking shot Chris Petit pulled off in Bristol for "Radio On". Sinclair's characters - often simulacra of himself - look up at the blank, reflective windows, or down at the equally impossible to read motorway junction. I try to look beyond the hotel to the sign gantries and wonder if it was here that Jack Whomes, brother of convicted Rettenden Murder John staged his traffic-stopping protest? This spot, where roads meet and join to form the last crossing of the Thames, is marked. It's a here-or-nowhere moment. A final opportunity to cross the water or remain on the north bank all the way to the coast. A crossroads of last chances. As a pedestrian though, I'm condemned to remain.

West Thurrock is a marginally energised take on Purfleet. A long string of communities, differentiated only by custom and local knowledge. Essentially the road is a long terrace, punctuated by views through to the riverside industry, which looms large over the Victorian homes. My feet are starting to drag, and a detour into the industrial zone to find the tiny church of St. Clement, eclipsed by the soap factory, just isn't practical today. As I cross the unmarked boundary of South Stifford, the unmistakable waft of skunk permeates the air. A front door bursts open, and the lazy Saturday afternoon drone of traffic is suddenly interrupted by a volley of barks. A squat, balding character weighed down by heavy links of plated chain swaggers into the path with a fistful of dog leads. Ahead of him, a pack of short-legged, bull-nosed terriers slaver and skitter, blinking in the light and scuffling for freedom. He presses a phone to his ear and yells into it. I wonder how I'm going to write this into my journey without pressing all the stereotype alarms? A group of Burberry clad young guys head out from a side-street and knock a nearby door which pulses with low-frequency reggae. No-one answers so they slink off, laughing and kicking each other from behind. I feel like I'm in a cartoon of Essex. All the mis-spelled sign boards of Dagenham, the mock-country pubs of Barking, all the things I could edit out of the Essex I'd experienced - and all of the liminal spaces and curious corners I could highlight in their places! But now this blew my cover. In the gravity of Lakeside, the gusting litter reflects its franchised restaurant chains rather than the line of local chicken take-aways. I'm an imposter here. I'm not spending any money.

I realise that I'm arriving in Grays. There's no sign or specific moment of transition - this road feels endless, though I've begun to wonder if I'm inexplicably looping by the same few terraces, the same tired little newsagents? The only real signifier is the change in the roadsigns - Southend is now a destination. Out of the gravity of London, beyond the skin of the Orbital Motorway, it is again acceptable to refer to regional destinations. I'm fooled into thinking the end of the line is nearer than it has seemed for most of today, and I'm spurred into a final push. I don't really get into the Town Centre, skirting the edge towards the station and seeing the square, modernist tower of the State Cinema glowering over the bus station. I'm tired - so tired I misread the station completely - heading for the bay platform with an infrequent service via the route I've travelled today. I realise there is a train soon via South Ockendon, but it's on the other platform. I stumble idiotically around looking for a way to cross, before finding the dank subway just as I'm about to give up and wait for the next train from the bay. I'm not sorry to escape Grays, even with the Lakeside-bound hordes sharing my train. It's been a long, tiring and dusty day which has already left me feeling confused and curious to research these odd surroundings. I'll need to come back here to pick up this route at some point, but I'm a little afraid of straying out into the open country of Essex. The rural gothic of the mysterious east beckons, with its freight of folk tales ancient and modern.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

I hesitate to tag this as a 'London' post. It is marginal, in the shaded zones at the edge of the map. As this walk takes me further from the city, I start to look for an edge - the M25 is too obvious, and the city's gravity extends far beyond it into the vampiric region which sucks the economic life out of Southern England. Maybe the countryside that divides Essex from the London Boroughs? That almost non-existent band of greenery is all too easily missed - an overgrown car park of a decommissioned roadside pub readily mistaken for a nature reserve. The truth is, I don't have an easy edge against which to snap my definition - and if Southend Airport is now 'London' too, perhaps I should give up trying? Perhaps this whole esturial swathe is now London too? The glottally punctuated accents, the harsh tang of heavy metals in the air, the constant drone of tyre on tarmac - they are all London's trademarks - and they're with me as I walk. I was equally hesitant about picking up this project again after a pleasant festive season. It felt like last year's work - a snuffling away at the margins in an attempt to walk off the seething frustration of a year spent in limbo. It felt derivative - it had all been done by hardier souls with a better turn of phrase. Was there anything left to discover our here? All the shallow gangland burials unearthed decades ago, all the surprising vistas captured by photographers with lenses long enough to avoid actually visiting the edge lands. If today went to plan, I'd walk off some edges and into known unknowns - stations a mere half-hour from Fenchurch Street which felt desperately remote on foot. I needed to recalibrate my scale to understand how this journey, too short to read a book or hear an album on the rails, was a minor epic now I was walking.

Heading out to my starting point, I realised that I might have to rethink today's objective. Getting to Beckton isn't quick, and with the train lazily timed due to engineering I had a fairly late start. I rumbled around the Circle to Tower Hill, made a quick dash to Tower Gateway and settled into a DLR train which slowly but surely took me out of the city, past the recent history of my walks once again. It was years since I'd arrived at Beckton this way on an exploratory trip to cover the DLR. I remember feeling like it was some impossibly remote outpost - definitely not London back then. Since I've shaded in the territory between the city and the Alp this view has changed of course, but it still feels like an ending. The ski-jump of the unfinished ramp over Gallions Reach ascends to cross the tracks, its post-modern adornments which should have given entrance to a new river crossing blasted by wind and particulate matter. I start walking immediately and with perhaps a little too much enthusiasm. I need to get moving, pushing into the strengthening wind but mercifully dry so far. I turn north, the green slopes of the Alp ahead - and I feel almost guilty for not climbing it today. After all the strange symbolism I've invested in this artificial mound, it seems odd not to pay tribute. I pass by, climbing the on-ramp to the A13: boiling with traffic, the rare gaps between cars filled with spiral eddies of wind-borne dust. This isn't quite new territory yet - I'm passing the vast Sainsburys store I visited on my first trip out here, the road curves steadily around it, hugging the white sheds of the retail park. After skirting the connection with the North Circular nestled beside a Waste Transfer Station and steeped in the aroma of decaying vegetable matter, the road bucks and rises in front of me. A swathe of reeds and a slender curve of brown water below indicate approximately where the River Roding becomes Barking Creek and escapes the tightly walled channel it has followed from Ilford. Looking north, across six lanes of shrill white vans, I see the ponds and inlets of Cuckolds' Haven - another walk where I'd turned aside, unsure of my right to roam and cursing my reticence. From the shallow bridge, the flood relief barrier is barely visible as a huge turbine blocks the immediate view. Only the blast of cold, esturine air gives rumour of the Thames. Creekmouth spreads across the southern view - low-tech industry and scrap, the town of Barking tucked safely away to the north. The road stretches ahead somewhat uninvitingly in a concrete-walled trench. I wonder if this is a sensible plan after all?

The A13 is a dividing line here - north of the road is civilisation, with solid and reliable 1930s housing schemes butting up against the road, built for the future car owner with easy access to everywhere. South of the carriageway is the sliver of industry which skirts the marshy banks of the river. Abandoned power stations, rusting networks of de-purposed pipework, bored security guards who seem to have been forgotten by everyone except the payroll. They just keep turning up, crumbs on the regulation navy sweater, cap at an angle. Are they stopping me getting in - or out? I cross a footbridge to the northern path - mostly because I see a filling station with a sideline in coffee. I'm the only non-driver in the place. The assistant spits "No fuel?" disbelievingly before reluctantly scanning my Nectar card. I shelter next to a battered tump of greenery outside the garage to stash my purchases and shoulder my bag realising that there's really no provision for leaving the place on foot. Refuelled with the curious mix of caffeine and warm milk I increase my pace. I'm feeling a little post-viral, below par and wonder if I can really achieve quite what I've aimed for. Right now, it's good to be walking but I know I'll tire faster than usual. Walking into the wind doesn't help - my face feels raw and bitten, my knuckles turning from red to white and back. The road is relentless. The surface noise has a hypnotic regularity. I check my maps and note I'm edging onto the last page of the A-Z. There are no more of the comforting blue continuation markers on the right edge of the book. When I bought it, almost exactly twenty years ago I couldn't imagine who needed these maps of distant suburbia, so impossibly far from the core of things. Now I was about to leave the map and I felt a pang of anxiety. This wasn't going to be London at all.

The road continues, still describing a shallow arc across the flat floodplain between the River Roding and Dagenham. The route is lined by a sound-repelling perspex fence as it begins to rise above the low blocks of housing on the northern edge. A green space opens out, stretching along the line of the railway which passes beneath the road but above the arrow-straight silvery line of Mayes Brook, heading south towards Barking Creek, encased in a narrow ribbon of green which extends along its route from the old A13 to this new interloper. North of here, the banks are reclaimed and offer a perimeter to the leisure zones of Mayesbrook Park, but this stretch is neglected by all but the most intrepid of dog walkers. This three-level crossing of routes marks something of a boundary. As I descend from the bridge, the first hint that walkers will be barred from the route at some future point are mooted by the signage. This is a temporary prohibition in fact, to account for the narrow and crumbling blue steel viaduct which carries a meagre few lanes of the A13 above the junction with Ripple Lane - its own earlier incarnation. The need to evade this junction is clear - aside from the flyover this is essentially a suburban roundabout - the northern flank surrounded by tired council dwellings and the southern given a view over the great Ford Motor Company water towers and wind turbines. Wedged into the triangle of land at the western edge of the junction is the Thatched House - a barricaded pub of currently uncertain status. Its vintage 'Double Diamond' sign still pitched on its high 1930s chimneys, the car-park off-limits and serving as overspill from the nearby junkyards. The whole place a grim and solemn roadside reminder of a convoluted, sorry past. The pub appears to remain a notable venue for African music and cuisine, but right now it is a dormant and oversized red brick behemoth of the type which adorned every well-planned municipal estate at first. A little further ahead, across the dual-carriageway, the Ship & Shovel presents another face of Dagenham nightlife - a displaced cottage style public house, oddly truncated and cluttered with unrelated vehicles. It looks as forlorn and menacing at the Thatched House, if a little less decommissioned. Edging around the traffic island and back onto the main route, I'm soon forced off onto an ancillary track. This appears to be the perimeter road of a new, tidy development of small family homes. At the end of the access road, I'm returned to the shuddering heave of the A13 as it passes Castle Green - a gloriously ungoverned tumble of green space fronting generous sports fields. As I draw nearer A series of curiously jumbled silhouettes on the flat grey sky resolve into local celebrities - inspiration for the pupils of the Jo Richardson Community School. Here on the edges of the city, the heroes are ultra-local in response to the reputation for non-integration. Casual racism was formalised into BNP council seats, and is now offset by naming public facilities after notably radical Socialist MPs. It's hard to know if it works - there's a metallic tang to the air here which reflects the sharpness of the knife-edge Dagenham sits on. There's a lingering sense it could collapse into either violence or utter indifference at any point as I navigate the slalom course of wind-toppled recycling bins which line the footway.

The path leaves the road here and skirts the pithily titled Dagenham Leisure Park. It appears in fact to be something of a relic - a former strip-mall of DIY retailers in the Midwestern vernacular, transplanted to the fringes of the old A13. With Lakeside now a short diesel-burn away, and with the main road curving away to the south on elegant stilts, only a cinema and a range of fast-food restaurants remain among the generous carparks. Footsore, lacking energy and desperate to use the facilities, I enter McDonalds. The monotone of the windy road is broken immediately by the screams of children, the cackling laughter of teenagers and the esturial admonishing of parents. It sounds hellish after the weirdly alluring swish of tyre on tarmac, but a cheap refuel beckons. I tough out the torture, pop painkillers and return to the road, my coat buttoned against the bitter wind. My road from here on is the A1306 - the redundant ghost of the old A13, fringing the residential edges of Dagenham as they break on the industrial foreshore. First though, there is a last knot of civilisation - a barricaded Indian Buffet restaurant which claims to be the 'largest', next to a much newer and far more capacious establishment which may well have caused this sorry end. There are mis-spelled signs and curious mash-ups of taxi office and take-away - but photography seems wrong here. I gorged on ruin-porn in those first few shuttered yards of Fieldgate Street. Here, away from the planning blight and regeneration schemes, it feels less edgy and more forlorn. Everyone should have to walk the mile from Dagenham to Rainham, across the Beam River and off the A-Z, before they critique local planners. It signifies the impossibility of making a community work by buildings alone. A little way from here sits Becontree, for many years the largest municipal housing scheme in Europe, radiating spurs and crescents of good, solid homes like an incomplete crosshair on the map. But here at the edges, it doesn't feel planned or controlled. It feels abandoned. Just before I cross the old A13 to head south I notice a new development with a street name which captures the mood: Passive Close.

Bridge Road turns away from the road, towards a Tesco of epic proportions, crossing the reedy twist of the Ingrebourne River. I could head directly for the station here to end what has been a challenging first trek of the year, but the river interests me, and I want to see the marshes before I make a definite decision not to press on today. Three more miles? Surely I could manage that. Lamson Road is an industrial short-cut, taking traffic away from the town and along a dusty gully which parallels the river as it becomes Rainham Creek. The lack of development ahead means the dry, cold wind howls at me as I turn east. I'm chewing grit and sucking dust I don't dare to think about. At the next turn south onto Ferry Lane, an official footpath is signposted. I climb onto the ridge and the marshes open before me: a swaying plain of grass and pylons trapped between railway and road. To the south the elevated A13 severs the view, the heaps of landfill rising beyond. I set out a little way south along the path, still thinking that maybe I could cross the marshes today. A stylishly rusted iron signpost, digits and destinations marked by stamped-out sky-coloured absences, tells me it's almost four miles to Purfleet. I decide this is the spot to call this walk finished. I stand for a while, looking at the marshes and watching the High Speed trains flash by. I've been carrying a key to my parents' flat for years, but since the turn of the year I've been uncomfortably aware of it - a cold metallic pocket weight, linking me back to a year of anxiety and a place which is now just a memory. I'd always thought I'd go somewhere meaningful and memorable to ceremonially dispose of it - but I'm suddenly taken with the idea that this place is perfect. This seemingly endless swathe of bleak, open marsh where almost anything can - indeed has - been hidden. Somewhere things can disappear. A place without - and perhaps beyond - memory. I unlink the key from its ring and pause. Feeling the cold metal in my wind-dried hand, I wonder if this is such a good idea. To ditch the symbol in a spot which I'm sure I could never relocate exactly, and will probably never knowingly revisit? Of course it's perfect! I marshal my thoughts and before I can reason further, hurl the key as hard as I can into the sluggish reedbeds of the Common Watercourse. So hard in fact it almost reaches the clumps of tall grass on the other bank. But it's gone - beyond retrieval, the ripple signature settling into the still green mirror. The wind swirls and I see a party of walkers heading in from the marshes. I snatch a quick picture for posterity: grey clouds marching swiftly over an austere powerline panorama. A train from the continent roars by. It's time to turn for home, the unlikely ceremony complete and a long, difficult chapter closed.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

When I've mentioned that I'm curious to walk the A13, people have looked a little quizzically and asked, simply, why? I suppose they're used to my manifold topographical obsessions, complicated literary mash-ups and generally curious nature. Of course, roads were a very early interest - as a boy I'd scrawl imagined maps, but rather than pirate treasure they featured complicated interchanges, improvement schemes and Ministry of Transport approved signage. My interest in networks has never gone away - my railway obsession, the desire to map and understand London. However as a surprisingly - and perhaps given this interest, illogically - unlicensed driver, roads are a vicarious and distant pleasure. I recently began re-reading Iain Sinclair's "Dining On Stones" - a semi-mythologised walk out of the city via this route. Ten years later, with more exploration of my own under my belt the text made a great deal more sense. But it also posed questions about how the post-millennial fringes of London were changing, and how Essex and the city interacted. Sinclair's text is amusingly self-parodic, pitched somewhere between nostalgia and dystopia. That has actually always seemed a good measure for the little of the road I'd walked - and is perhaps a pretty good starting point for the whole of the British road network. A creation of the 1920s, these numbered and classified routes have drifted in and out of logic over the years as they have been re-routed, bypassed and decommissioned. Walking a road from origin to end-point seems a little out-of-character maybe? After all, much of it will be open country and far from the edgeland fringes and grimy city channels I seem to prosper in walking. But it feels like a project worth undertaking - simply because it's there to be walked. And so, on a blustery but strangely warm December morning, my trudge began...

Setting out from Liverpool Street, I head through the fringe of the city and along the almost-deleted street of Houndsditch. The development encroaching on this ancient byway threatens to overwhelm it completely, hemming it in with tall towers. I make for the spire of St. Botolph Without Aldgate, once beleaguered by traffic but now subject to a public realm scheme which will create a pedestrian friendly approach. I pick my way around the works, noting how the wind has risen now I'm clear of the channel of office blocks - it's not a cold day, in fact it is perhaps oddly mild for early December, but the wind chills me. I grasp my cup tighter and navigate a little to the west to find Aldgate pump marooned between the arms of a junction and crumbling slightly. Some nonplussed and rather troubled looking Asian tourists regard the pump and the general area before snapping quickly, uncertain of what this monument represents, and retreating west. I take the opportunity for a picture - the official start of the A13 and therefore the embarkation point for this walk. It is an inauspicious, dirty and noisy start - the road east is a confusion of development sites, cranes set against a slate sky. Like always at the start of these wanders I doubt my purpose, doubt even my wisdom in being out here. But it's time to set off. I gently - and perhaps rather pointlessly - nestle my cup in the base of a now decommissioned litter bin and turn east. The A13 is a disputed route as many of the original roads designated in 1922 now are. There are some solid facts - it originates in the city and heads east, taking in Barking, Dagenham and the southern reaches of industrial, esturine Essex, before depositing daytrippers in Southend-on-sea. Officially it then presses on a little further to the shadowy Ministry of Defence bolthole at Shoeburyness, just a step away from the officially designated 'Danger Zone' of Foulness Island. Beyond London, the route is up for grabs. Once out of the confining grip of the city street pattern, it heads along a several-hundred year old alignment which served the docks, before turning a little north to provide the main drag of Canning Town. Here the first bypass starts - a swathe of much improved road takes the route a little south, ploughing through the previously empty industrial wastes towards a new crossing of the Roding. When I explain to locals that I'm walking the A13, they perhaps understandably ask "Which A13?"

For now though the route is clear, and with Aldgate behind me I turn a little south and then east onto Commercial Road. This stretch of route is grim - an unrelenting parade of closed and shuttered shops on a Saturday morning. Some it seemed were aiming to make a feature of their distress - a little bit of imported Spitalfields glamour perhaps? Otherwise though, it was a mix of fried chicken emporia, sub-continental clothing retailers and student housing. The broad, empty road leads away from the city towards Limehouse, taking in some of the most contested territory in London. The most deprived wards of Tower Hamlets - indeed of the UK - crashing on the affluent beaches of Docklands. Mostly, it seems to work - the repurposed viaducts carrying the DLR serving as a firebreak across the Isle of Dogs, severing gloomy Blackwall and Poplar from the shining towers of light. As I discovered on an earlier walk, it's not easy to move between the mainland and the Isle - perhaps designedly so. First though, the tower of St. Anne's Church looms over the railway bridge, the road turning a little to circuit the northern fringe of the churchyard with its curious monuments. Beyond the church a tall tenement of dirty brick buildings claims to be a "VIP Garage". It very likely isn't. Crossing the canal, the road becomes East India Dock Road - a georgian thoroughfare which retains some of the fine townhouses which once lined both of its sides. Traffic is officially encouraged to leave the A13 here, taking Aspen Way and skirting the fringe of Canary Wharf on a road which seems to be neither public nor entirely private either. Sticking with the old route, the chill wind has finally challenged my coffee-filled bladder and I'm forced to leave the route, ducking into Chrisp Street Market. I've passed by many times but haven't really strayed far into the historic precinct. Historic because this humble concrete chasm leading to a purpose-built market square was the first such pedestrianised shopping area in the UK. Since its creation for the 1951 Festival of Britain, this pattern has been repeated endlessly and thoughtlessly over the British Isles, sometimes to terrible effect. Here though it worked - and it remains prosperous, inviting and has the sense of being a resolutely local spot which bears evidence of investment and renewal - including a fine new library building. There is a literal whiff of gentle gentrification - the range of ethnic food outlets in the Market participate in a regular Street Food fair for instance. The confusion of drifting smells from Chinese food, pie and mash and Indian cuisine purveyors signifies this might well be a good thing. I'm tempted to linger - but there is walking to be done. Leaving the market by the side entrance I'm confronted by the mass of Balfron Tower looming over the Brownfield Estate. Turning my back on it, I see it is defiantly opposed by a house-sized mural of a puppy - the kind of over-sentimentalised, big-eyed creation you'd see on a cheap birthday card. I leave the tower and the market's unlikely guardian to their own devices.

Back on the A13, the northern fringe of the road is also the perimeter of the Lansbury Estate, with generous green spaces and local facilities evidently still functioning. This is the kind of philanthropic planning which the nation cries out for often, but rarely gets - and certainly not here. Now, along with Chrisp Street, managed by the slightly shadowy Poplar HARCA it soon peters out into a mess of projects on former public land: half-built towers and empty spaces with hoardings proclaiming future opportunities. Between these, businesses still sell fast food, SIM cards and tyres or front mysterious travel money operations. Suddenly, and noisily, the scene opens up as the Blackwall Tunnel Approach Road dives under the A13, the tunnel portals visible to the South. Looking north there is a strangely compelling view of Balfron Tower and distant Stratford with the ludicrous Orbit standing out from the former marshes. I take a wrong turn, coming to a dead end in a swirl of dry leaves and litter. Retracing my steps, I halt in the middle of the mess of footbridges crossing the tunnel approach to capture views north and south. The road is breathtaking in it's sweep and severity, and my onward route here is decidedly the minor player. The once proud road to the docks usurped by the north-to-south torrent of commuters and shoppers. The road is swiftly closed in again, hemmed between more new hazily public-private development and the grey prison fascia of the Docklands Travelodge. Tucked between here and the river, straddling the former East India Dock, is the Mulberry Place headquarters of Tower Hamlets Borough Council - expensively leased since 1993, with an equally profligate move to the former Royal London Hospital planned. The area is carefully managed to be as banal and inconsequential as possible, reflecting the strange belief that a deserted place is more secure than a busy, civic centre. I take a turn away from the main road here, following the dock wall which divides the carriageways of Leamouth Road. I know there is a strangely isolated service station at Orchard Wharf which provides an opportunity for sustenance beside Bow Creek. As I turn south a squall of wind stops me in my tracks. A mix of building dust and silt covers me, my sweater sparkling with silica and a salt grind between my teeth. I adopt a crabwise shuffle to edge around the open entrance of another new development of rental towers from which the dust seems to originate, and cross the street to find the garage. But it is gone. The windows boarded, the forecourt a screed of stones. The building looks oddly forlorn, swept by river winds and blasted by sand it is already peeling and crumbling. Still surprised, I retrace my steps towards the road. Change here is swift and absolute it seems.

Re-crossing at the confusion of lights at Leamouth Interchange, I'm struck by an odd sight: the new Lighterman's Point development towering above is fringed by a street of fine old terraced houses, diving off at an oblique angle and defiantly refusing to be part of the new zone. Aberfeldy Village isn't new - this colony beside the creek has co-existed, indeed been co-dependent on the dirty, industrial fringe of the River Lea for generations. Its new guise sounds more like a drug-trial than a locale - but we're reassured that 'AV-E14' is importantly not regeneration. That's a filthy and devalued term here in the Lower Lea Valley. This is reshaping, re-imagining even. I'm confused and confounded by this however: London has a terrifying housing problem. It needs a mix of accommodation and it needs it fast. These old, solid family homes are being replaced by blocks of student housing, one bed luxury apartments which house couples at best, ground-floor retail units for a zone with no centre. The line of proud, tidy houses are surely an essential part of the mix? Absent-mindedly picking this over, I climb the curve of the bridge which takes the A13 over the intestinal curl of the Lea. I can be in no doubt what road I'm on - all three lanes are proclaimed A13 by the overhead gantry. The views south are occluded by the road, but looking north I see the forbidden edges of the river where no path is available. The curves and bridges are familiar, well worn, often revisited. Landmarks stud the scene - remembered tower blocks at West Ham, the cluster of silvery columns of Stratford City, the ever present and never welcome Orbit. Descending from the bridge is leaving 'London' in some ways, heading out to the marshes. The road divides, the old route becoming Barking Road and dividing Canning Town with a mix of over-familiar high street names and local colour, while the new road is a non-pedestrian flyover snaking above the streets. I shop for food before rejoining the route as the bridge touches down. The pattern from here on is set: a broad cycleway and pavement set alongside the northern edge of the six-lane road. I pause to eat at a local exit for Prince Regent, sitting on the concrete podium of a telephone switch box. The old streets intersect the new at strange angles, the rooftops of Victorian terraces coming to a sudden, premature halt where the new road gouges through long-established districts. I set off again, and realise I'm getting strange looks and creating interest in passing drivers. It's perhaps not surprising - I'm a wild-haired, heavily bearded walker in a sweater and rucksack despite the December cold, and by far the only pedestrian for miles. Even the occasional cyclists look askance. Then it becomes clearer - the high fence and cameras fringing the bank beside me belong to the Newham Centre for Mental Health. I'm an assumed escapee. As I suck fumes and regard the featureless view ahead, I wonder if they're not right?

It is entirely a myth that traffic thunders. Out here at least, the sound of the stream of passing vehicles is a endless and metallic, ululating drone. On another day, in the peak hour, it might almost be silent - a string of unmoving red tail lights stretching back to the city. But on a December Saturday the cars flow steadily, punctuated by occasional business vans - their drivers pressing 'phones to their ears and chewing on thick hunks of sandwich as they shuffle lanes testily to gain a little on the cars doing strictly the correct speed. Here, as the gravity of the city weakens, the road speeds up. Hamstrung until now by a low speed limit which makes a mockery of its quality engineering, the A13 makes a curve north, skirting Beckton's retail parks and low-rise housing schemes. Of course the original route swevered too - dodging the swathe of industry between here and the River Roding and the vast gas and sewage metropolis which filled the alluvial flats between here and the docks. In the middle distance as I round the curve, the road bucks and weaves to the left. Beside the ramps of the next grade-separation is a tump of green, wooded but with a bald and exposed top. Beckton Alp, seen from this direction at least, is impressively elevated in an otherwise level plain. The iron palings which edge the summit freshly blackened and adorned with new graffiti: All power to all people. Denuded of foliage by the season, I see a white-coated dog walker make the summit and stand for awhile, companion capering around - a distant flickering stick-animal. I cross the A13 by the footbridge, towering high over the six lanes of chaos and challenge below: cars fence for position, forcefully occupying the space just left by others as they weave, looking for some tiny perceived advantage or realising too late they need the exit. I resolve to get all the way to the top this time.

The entrance to the Alp is much as I found it last time - an anonymous metal gate with a businesslike padlock attached to a drawn back hasp. My fear that this would be deployed during my visit was unfounded, and this time I'm less concerned. I enter the gateway and start to ascend, zig-zagging back and forth and dodging the inventory of what appears to be a small colony of nocturnal inhabitants: Polish lager cans, discarded jeans, extinguished fire-pits, condoms. The path is cracked and fissured by tenacious bramble stalks reaching for sunlight. It's easier going in Winter though, with the overhanging foliage and colonies of midges absent. I see the dog walker below, leaving by the other gate and decide it's time to make my own assault on the summit. As I reach the end of the official pathway I see a gap in the fence where the bars have been bent apart like a cartoon jailbreak. I size up the gap - it's pretty big, but then so am I. I pass a leg through, stoop and swerve to get my rucksack under the bar, then I drag a second leg through and I'm on the other side. The reason this area is gated off is immediately apparent: to my right is a decaying wooden platform dating back to the ski-slope endeavour. It is clearly a pretty risky structure, and only a complicated insurance claim could follow any attempted use of it. Looking left up the slope however there is a well-worn track which curves slightly towards the summit. A quick scramble, assailed by the wind gusting in from the estuary, and I'm at the top. Suddenly all of London is before me. It was impressive from below, but here, unhindered by the trees it is magnificent. Ever present, east and west, is the snaking A13 - a ribbon of dim lights in the increasingly gloomy afternoon. Looking south, the sugar factory at Silvertown towers about the low rooftops of North Woolwich, and beyond is the glowering rise of the Kent coast. Looking east, following the road, is a maze of warehouses and retail hangars between here and Barking - all clad in the same corrugated shells, as white as the goods they are peddling. The flood barrier casts a shadow over the brown snake of the River Roding, and beyond? Well that's where I'm heading...

Descending from the Alp I catch a bag strap on the fence leaving it mildly distressed, but perhaps surprisingly I note it doesn't worry me. I'm aware I've been in a near constant state of activation for months - anticipatory, dry-lipped anxiety has become the everyday state. The mess of finances and legalities has begun to seek a proxy in other, worldly concerns and a bit of mild rucksack damage would normally feel insurmountably challenging. Like an overtightened cello string, I've involuntarily vibrated to the noises around me. Oddly though - and I can't stress how rational I usually am, or how ludicrous this sounds - I feel like I've left something up there in the wind, swirling off into Essex. I start homeward by picking through a retail zone unusually carelessly. I'd normally be concious of my oddness, my separateness from the line of consumers' cars. Attracting attention by trying too assiduously to avoid it. Soon, I'm treading an old railway path cutting diagonally towards the docks. The wind swirls litter and autumn leaves across my path. I'm starting the long journey home feeling oddly calm.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.