Via Antiqua: By Watling Street from Kent to London

Posted in London on Saturday 28th April 2018 at 11:04pm

Today's walk had crept upon me unexpectedly. The weeks had tumbled by unusually swiftly and a confused calendar thanks to rail works and changing plans meant I'd not prepared myself. In reality, the process of planning a walk isn't as onerous or complex as I often make it sound: usually, it's a germ of an idea followed by a cursory study of a map to ensure there is actually a path to follow. The research comes afterwards, reconstruction undertaken with feet smarting and imagination fired. There are numerous half-formed plans circling at any given time - and sometimes one leaps forward as an essential next step or perhaps just won't quite stop cropping up, coincidentally or otherwise. It was just one of these nagging presences which drew me south of the river again today... I felt like I'd been haunted by Watling Street for years now. I had a map of Roman Roads as a boy on which I'd been shown how close my home was to the confluence of Icknield Street and Fosse Way - but it was the improbably perfect diagonal trajectory of Watling Street which most intrigued me. After lying dormant in my imagination for years the road had resurfaced - first in print with Jon Higgs state-of-the-nation travelogue and Iain Sinclair and Alan Moore tramping Steve Moore's 'psychic circuit', then it began to assert a presence on the ground seemingly wherever I've walked in recent months. When I've looked at maps to plan future excursions the arrow-straight incision across the north of Kent has been impossible to ignore. The red slash of an A-road scythed across the map like a fresh, clean paper cut. Walking roads - ancient and often less so - has some precedent here, so it didn't feel strange to plot a course along the route as a potential future trip. Yet I still filed this one away, for an especially rainy day perhaps - because surely a straight line couldn't make for the kind of convoluted itinerary I'd prefer? But as I prepared hastily for this trip, I couldn't quite shift the idea that I needed to connect up previous walks via this old track.

And so I made my way to Charing Cross to take my pick of the carriages on an empty train to Dartford. The rumble and shudder through the southern suburbs was becoming very familiar now but felt somewhat eerie as I appeared to be almost entirely alone onboard. The train snaked through the refurbished London Bridge station - grey plastic panelling and swooping escalators descending into the re-imagined undercroft - and left the gravity of the city. I let the greenery of the suburbs drift by the window while I pondered my changing relationship with Kent over the years. On my first excursion here I was entirely unimpressed: the ponderous amble through the middle of the county by train was dull and charmless, ultimately leading to desolate, unremarkable Ashford. I revised my view over subsequent visits - especially those involving the northern coast which had grown to fascinate me. Now, after a sequence of walks which had dallied along the border of the county, I was curious to exit by this most ancient of trackways. It felt like a fitting way to mark a re-evaluation. The train slowed after passing familiar ground at Crayford, and high above the marshes I could see the towers of the Dartford Crossing and the distant glower of Essex on the horizon. Lurching across the junctions where the splayed branches of the North Kent Lines finally reconstituted themselves into a single railway, the train slowly came to a halt at Dartford. Below the raised platforms of the station, I spotted the former millpond fed by the River Darrent which was busily being redeveloped as a waterfront living opportunity. The narrow platforms and dated, gloomy exit stairs led out to a modern but down-at-heel ticket hall tacked onto the rear of the Borough's grim civic centre. A bridge took me over the busy inner ring road, descending near the red brick flank of the Orchard Theatre. Dartford was a town which had willingly conceded its soul - and just a few miles along Watling Street the vast hole-in-the-chalk of Bluewater sucked the income out of the locals with alarming efficiency. Dartford mopped up the rest via a network of pound shops, chain pubs and gambling opportunities. I headed for the centre of town where Spital Street followed the ancient geometry of the Roman road, heading in from the settlement of Vagniacae at nearby Springhead. The site there had been a centre of worship before the coming of the Romans, with evidence of Iron Age rites near the pools where the River Ebbsfleet rises. The tradition of worship and offering continued, with the Romans turning the site into a major complex of temples - and now Bluewater stands close by, drawing its own pilgrims. Perhaps grim, inward-looking Dartford has always been the poor relation hereabouts? I turned west on Spital Street, suspecting that any hint of interesting shopping opportunity lay along the pedestrian zone to the east. The narrow road was lined with abandoned shops, proper old-fashioned independent cafés emitting tempting breakfast aromas and a brace of repurposed theatres deputising as evangelical churches. I felt uncomfortable, though there was nothing especially menacing about the place. Perhaps in fact a little edge would have helped. Dartford just felt tense and contracted: out of the gravity of London despite being (just) within the grand circle of the M25. I began to climb West Hill, finally falling into step with the historical route of Watling Street as it passed the Royal Mail sorting office and the crumbling remains of The Lock-up: Dartford's first police station and latter-day dosshouse for itinerants. It was good to be walking, and a relief to be leaving this oppressive town.

The last stretch of Watling Street within the boundaries of modern Kent was a drab channel through suburbia, with occasional bursts of local shops which were invariably closed for business. The land rose gently ahead of me as I crested the narrow tongue of high ground which separated the Cray and the Darrent. It struck me that only a few weeks ago I'd been further north on the bleak marshland which sat between this road and the Thames. Up ahead was a junction with the B2174 - an inauspicious number for what was an early incarnation of that most British of institutions, the bypass. The road arcing south around Dartford and avoiding the narrow progress of Watling Street through the town was opened by the Prince of Wales in 1924 - or perhaps by an overzealous worker who severed the ribbon in advance of the royal scissors. The press of the time dubbed this the 'New Watling Street'. The road meets its much older counterpart at this rather inconsequential roundabout which, since 1965 at least, has formed the border between London and Kent. Looking west there a proud sign advised motorists that they were about to enter the London Borough of Bexley, while to the east Kent offered no such welcome. There was however a marker here - squarely between the poles of the sign advertising the roundabout an 1861 Coal Duty post remained in place and in good shape. As my excursions have taken me further out into the suburbs of London, these administrative obelisks have become welcome markers of my progress back towards the City. Finding one here today felt like a first indication that this might be a more interesting walk than perhaps I'd expected. There were few other signs that I'd passed into London - the line of former council houses didn't break step, even when the insignia on the wheelie bins changed. Beyond the junction, the road led downhill once again, into the valley of the Cray. There was a brief thrill of familiarity as I noted the retail parks which had greeted me when I'd entered Crayford from the south. I braved a pair of scornful, braying locals concealing cans of Special Brew to snap a picture of the clock tower before heading across the river. Crayford was much as I'd left it a few short weeks ago - a busy churn of suburban life shot through with traffic heading for Bluewater or Lakeside. It was only after a few minutes of brisk uphill walking that I realised my plan to attempt this walk largely without a map had failed me. The road had turned slightly north to cross the river and I'd blithely headed straight on. The High Street began to dwindle as I climbed, the local shops being replaced by a string of takeaways and abandoned vape shops. I knew this wasn't where I should be and instinctively stopped to consult the map. I had indeed gone straight ahead - but the kink in the route over the river had thrown me off course by about 45 degrees. I trudged back downhill, acutely aware I was passing people I'd just moments ago huffed past on my ascent. I adopted a facial expression which I hope conveyed that of course I'd meant to walk up the hill and back again so soon. Back at the bridge I turned southwest, immediately recognising the route I'd taken in reverse along London Road while walking along the Cray. I was back on track.

Watling Street was dominated for a few miles now by suburban encroachment. The green spaces of Shenstone Park and Bigs Hill Wood gave some relief from the parade of recycling boxes and wheelie bins as the road made a steady climb away from the Cray valley. I'd been intrigued by the near life-size silhouette bronze sculptures of cows in Shenstone Park on my last passing, and getting closer enabled me to read more of the story: David Evans & Co. made silks nearby, using the Rubia Tinctorum or Common Madder plant to create a vivid red dye and maintaining a herd of cattle on the site to provide manure to fix the colour in the cloth. Beyond the park, the road returned to suburbia, still climbing as I faced down a cold, persistent drizzle of rain. The rise reached a plateau at Pinnacle Hill - a rather overstated name perhaps - and the view ahead opened before me. This was Bexleyheath, as announced by the strange tumble of gables and brick of the new Civic Centre. For many years the busy corner of Watling Street and Erith Road was occupied by the computer centre of The Woolwich Equitable Benefit Building and Investment Association which those of a certain age will recall being advertised in a chummy inclusive fashion: "I'm with The Woolwich". In the heady days of 1989 they made a bold move to relocate their HQ into a purpose-built block on this corner. The heady days of demutualization and acquisiton that followed were a small part of the build up to the crashes of 2007, and by 2006 the Woolwich was part of Barclays PLC and the HQ was closed. The Borough stepped in, selling the site of their civic offices to Tesco and snapping up the Woolwich site as a bargain. The redeveloped area was disarmingly quiet at the weekend - built in part as a plaza to cap the busy High Street, there's little need for people to press on this far beyond the shopping centre. The Civic Centre towers and tumbles above the crossroads, facing London defiantly, the exterior only hinting at the impressively refurbished, modern facilities within. I waited at the crossing for what seemed like long minutes, sharing my wait with a couple off to a wedding who were impatient to get out of the rain - there was a concern that suede would matt and hair would frizz. I considered my own appearance, bedraggled and damp, red-faced from stomping the hill from Crayford, and figured that the well-turned-out pair had little to worry about yet.

After crossing Erith Road, Watling Street becomes Broadway, the main drag of Bexleyheath - and a relative newcomer to the area. In the early 19th century the wild heathland pressed directly against Watling Street and there were few houses in the area save for the hamlet of Upton where William Morris decided to locate his 'palace of art' - The Red House in 1859. The construction of the house, which was swiftly absorbed into the suburbs as the commercial centre of Bexley shifted onto the heath and Upton was swallowed, largely bankrupted Morris. He was forced to sell up in 1865 vowing never to return to the house or to Upton. Now, two broad bypasses sweep traffic north and south of the centre, leaving Broadway to continue as a pedestrianised walkway on the line of Watling Street. This largely featureless, pavement, part-covered by an inaqequate awning, delved between a carpark and an extension to the 1984 shopping centre including a huge Sainsbury's and a multi-screen cinema. As ever I was walking against a tide of shoppers heading for their cars or buses home. Across the expanse of parked vehicles, the white chequerboard flank of the utilitarian Magistrates Court gleamed, all the better for a soaking of rain to slough away the traffic grime which still streaked the less exposed rear of the building. This wasn't, I'm sure, how Bexleyheath wanted to be introduced to newcomers - and it seems that the ceremonial march along Watling Street didn't do the place justice at all. As the enclosed alleyway which I'd been walking burst out into surprising sunshine, the street opened out into a much redeveloped and bustling market square. At the centre was the Clock Tower erected in 1912 to commemorate the coronation of King George V. The architect, Walter Epps, designed the tower with niches which he hoped would in time be filled by busts of the Royal Family which has largely been the case - though in 1996 a bust of William Morris was allowed into the hallowed company to celebrate the centenary of his passing. The tower was a focal point in a pleasing pedestrianised area which stretched along Broadway, taking full advantage of the straight-line of the Roman Road to create a promenade between the modern shopping centre and the more traditional street scene to the north. In 2000, to celebrate the millennium, the bells in the Clock Tower rang for the first time since they were silenced by the Defence of the Realm Act in 1914. I was surprised how much I liked Bexleyheath - in essence just another fringe centre which ought to feel as oppressive as the hugely redeveloped Wood Green. But here, just enough of the town had survived, and just enough of the character of a place which was not ancient but remained proud seemed to linger. I decided to stop for refreshments and watch Bexleyheath pass by for a while.

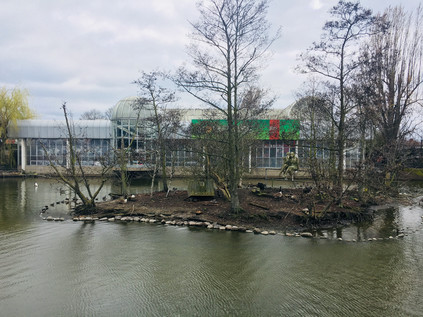

A consequence of the long, straight course of Watling Street is the tendency of settlements to become drawn-out, straggling places - and Bexleyheath appeared reluctant to give up just yet. The twin bypasses rejoined Broadway to the west of town, and traffic was once more permitted to flow along the ancient road - though it was relatively sparse given the swifter route of the A2 carving through Kent a little way to the south. I crossed the junction of Upton Road, practically all that remains of the now subsumed hamlet, and where I'd turn south if I wanted to visit Morris' home - today though I pushed onward as Watling Street became the curiously named Crook Log. Opposite the apparently well-used leisure centre of the same name, the Morris Wheeler Gates of Danson Park proudly bore the insignia of Kent and its motto Invicta. This impressive green space was gifted to the Borough in 1925 having previously been part of the lands surrounding Danson House which remains at the heart of the park, with views over the ornamental boating lake. The house was built in the 1760s for Sir John Boyd, a prominent figure in the British East India Company, and there is debate about whether it was Capability Brown himself or his assistant and scholar a 'Mr. Richmond' who laid out the lake and parkland surrounding it. Little appears to be known of this mysteriously acolyte save for the plans for Danson Park which survive in Bexley's archives. By the time of Boyd's death, the area was already in use as pleasure gardens, and the association with recreation continued despite being threatened by its acquisition by Alfred Bean, a railway engineer and prime mover behind the Bexleyheath Railway Company who envisioned the area becoming a vast residential estate. On Bean's death in 1890 some areas were indeed auctioned for building plots, but by 1921 on his widow's demise, the Urban District Council acquired the land at auction. In 1937, Lord Cornwallis presented the council with the status of a municipal borough under an ancient oak tree in the park - and the Charter Oak remains enclosed within the park, and indeed in the arms of the Borough of Bexley. The park and house have benefited from much restoration in recent times, and it seemed busy with locals despite the rather gloomy beginning to the morning.

Danson Park marks a passing which would otherwise be hard to detect - from Bexleyheath into Welling, another long and drawn-out settlement which hugs the line of Watling Street. Welling, while perhaps not as significant in the borough's recent past, has a longer history. Evidence of neolithic occupation has been unearthed at East Wichkam, now wholly absorbed into modern Welling, but once a distinct village which once housed a temporary village of workers huts serving the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich. This link is celebrated with the loan of a 36lb Russian cannon which sits at Welling Corner, now largely ignored by passing shoppers but favoured by clambering children. The railway reached Welling in 1895, crossing the western end of the long High Street via a high brick bridge, and opening up lands north of the area for development by way of a station a short walk from the main street. The long stretch of shops leading to the bridge still maintained a prosperous and pleasant air, with a surprising diversity of stores - the usual suburban mix of chicken shops and cafés supplemented by craft stores and the like. Welling also benefitted from several major supermarkets setting-up shop in premises along the line of the main street rather than at some spot on the outskirts, thus ensuring a constant stream of pedestrians along the pavements. I was acutely aware that London was just over the next hill - at least the London which most would recognise as such - but this place felt full of provincial bustle. Perhaps Welling really was the last outpost of Kent - and the insignia on the gates of Danson Park referred to its triumph over the creeping suburbanisation of the borough? It might seem that London was close by, its inevitable gravity already pulling in road and rail, but ahead of me was a mighty barrier, and rising above the line of the railway bridge a distant green smudge against the grey skies signified Shooters' Hill. Rearing above the road, this formidable barrier had been easy to ignore until now. I tightened the straps of my rucksack and marched onwards, under the railway bridge with its rather impressive murals of Bexley life, including an image of the ill-fated and short-lived double deck trains of the Southern Railway. It was time to head back into the city...

Despite the grey skies and general gloom, the day was becoming warm and humid, and as I passed the last possible place I could rest before my ascent at the appropriately named 'We Anchor in Hope' public house, I decided that my best chance for an assault on the hill was to tackle it in one lung-busting push. Detours into the temptingly dark and cool Oxleas Wood to the south could await another walk, and the opportunity to stray into Woodlands Farm to see gambolling baby lambs needed to wait too. Instead I looked ahead at the straight, steep road disappearing into the tunnel of overhanging trees. At the foot of the hill a burned out car had collapsed onto the driveway of Thompson's Plant and Garden Centre, notices explaining that there was currently no parking or vehicle access. The air nearby had a taint of melted electronics and charred fabric. I edged uneasily around the stricken vehicle and began my climb. At first it felt surprisingly easy - the hill, though 433ft high was not steep on its eastern flank, and the walking was challenging but manageable. After a steeper and sharper rise near the summit which was more taxing, the road levelled a little near Eaglesfield Road. I turned north, puffing into the quiet park which sat on the brow of the hill here, and found a seat to survey the view back east. The description of the prospect from the top of Shooter's Hill written by Celia Fiennes has perhaps never been bettered - and remains remarkably accurate today. Fiennes was born in 1662 and never married, instead embarking on a series of tours of England which she undertook "to regain my health by variety and change of aire and exercise". Her memoir, largely intended for friends and family, was never published in her lifetime but has since seen the light of day, providing a remarkable contemporary account of the country as it thundered haplessly towards industrial revolution.

Shuttershill, on top of which hill you see a vast prospect ...some lands clothed with trees, others with grass and flowers, gardens, orchards, with all sorts of herbage and tillage, with severall little towns all by the river, Erith, Leigh, Woolwich etc., quite up to London, Greenwich, Deptford, Black Wall, the Thames twisting and turning it self up and down bearing severall vessells and men of warre on itIn the distant haze I could see the Dartford Crossing, close to where I'd set out earlier this morning. The suburban settlements along the railway and on Watling Street formed a continuous chain of red-brick smudges stretching from the horizon and ending near my feet. There was a surprising presence of green spaces too - not always evident from the ground, but nestled between developments and in the useless triangles abandoned where estates adjoined each other there were clumps of trees, patches of suburban parkland and expanses of municipal playing field. Kent shimmered in the distance, the Thames visible mostly as an absence from this vantage point. I pondered the walk to this point, and planned my next move. Since I was here on the slopes of this hill with its neolithic history it felt only right to seek out the Shrewsbury Tumulus where Steve Moore had anchored his esoteric visions of this neighbourhood. I would be treading in the recent steps of better writers and deeper thinkers once again, but it felt wrong not to make the short walk over the ridge to the mound. A meander through the quiet streets brought me to the mound, tall grasses and a bright swathe of wild flowers almost concealing its form. The corner site, fenced in and protected, was a quiet place in an already sleepy residential suburb. A curious peace lay across the Shrewsbury Park Estate with its fine 1930s homes glowing in the afternoon sunshine which had finally made an appearance. The parkland here was associated with Shrewsbury House which stood nearby and was rebuilt as recently in 1923, and was later purchased by the London County Council for new housing. The archaeological significance of the area was already reasonably well-known - but only one of the Iron Age tumuli survived even then. Watling Street likely long pre-dated the Roman road, an ancient track to a place of burial and reverence atop the highest point for miles around. I paused a while, intrigued by the apparently ancient route of Mayplace Lane which wound downhill towards the Thames. This narrow track had been paralleled by more modern routes, but still found its own meandering course down towards the shore. I noted its route for further investigation - intrigued by the suggestion of a route to causeways over the marshes. I'd been a little sceptical about the lure of this place which appeared to completely ensnare Steve Moore, working its way into his writing - even indirectly influencing the work of (the unrelated) Alan Moore with whom he frequently collaborated. In the work of both Moores there was a deep historical significance to place, and Steve had anchored his visions deeply here on Shooter's Hill. Considered alongside distant Shepperton in the west, the houses provided a fitting counterbalance of mid-century modernity. In these geographically distinct suburbs Moore and Ballard worked to redefine their environs in dark fantasies. Somehow their visions grounded London, pinning down its sometimes hazy character under a near-perpetual dome of cloud and drizzle, and providing a dream life for its suburbs.Diary of Celia Fiennes - 1697

I returned to Shooter's Hill near The Bull, a long established refreshment stop those who had tackled the ascent of the hill by coach and presumably wished to celebrate doing so unmolested. Now it promised suburban taproom character at London prices. The famous water tower leered above the hostelry, now a private home with unparalleled views across Eltham Common towards Severdroog Castle, or over the Thames to the aspirational environs of Galleon's Reach.

The western side of Shooter's Hill had seen work to flatten the climb during the 1950s when lower powered motor vehicles didn't always make the crest, and now the road dipped into a man-made chasm between the pavements. Walkers were consigned to the original gradient, steep enough to give me the uneasy sense of tumbling forwards and to conjure a dull ache in my shins. Much of the southern side of the road was occupied with the Memorial Hospital, now largely providing mental day health services, the grand gateway advised those with more pressing issues or injuries to head for the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Lewisham. Opposite the hospital and set back from the road, the Red Lion was preferred over The Bull for staging Mail Coaches on the route to Dover and remained an inn of a fairly unreconstructed nature - offering a special on pies and pints, and a full range of Sky Sports channels. Beside the pub, a terrace of five cottages stepped down the hill and it struck me how isolated a spot this must once have been. Shooter's Hill was, for centuries, synonymous with utter lawlessness. The slow climb and the wooded areas around the hill made the work of highwaymen all too easy - more visceral and far less romantic than stories suggest. During the reign of Henry IV the crown ordered clearance of trees along the edge of the road to prevent 'violent practices' yet these persisted - and indeed increased in frequency - for centuries to come. Even the practice of hanging the corpses of executed thieves over the road as a warning seems not to have deterred attacks, with Samuel Pepys describing in his diary for 1661 passing by "the man that hangs upon Shooters Hill". By the 19th century a substantial village had begun to grow on the slopes north of the road, while Eltham Common had been partly cleared to the south. The presence of a range of larger houses and follies such as Severdroog Castle had also altered the character of the area considerably. It was no longer necessary for Eltham to maintain two Police stations to manage the disorder in the area, as was the legend. My own nod to this history of malfeasance was to disobey signs ordering pedestrians to cross the busy street to avoid some apparently abandoned roadworks, and feeling justly proud for maintaining tradition, I came upon the crossing of the South Circular. I recalled standing at this spot while stormclouds massed over the city, pondering the walk ahead of me. Today I continued westwards into Blackheath, passing the former Royal Herbert Hospital which had, for over a century, housed veterans of British military expeditions overseas. Built initially to house those returning from the Crimean War, the facility opened in 1865 and many of the then-innovative design features arise from the input of Florence Nightingale who had been sent to the Crimea by Sidney Herbert, Minister of War and had formed very clear views on how casualties should be managed both on the field and back at home. Royal Patronage came in 1900 when Queen Victoria visited veterans of the Boer War at the hospital, then noted for its fine buildings and health-giving proximity to the open spaces of Oxleas Wood. The hospital remained in use as an Army teaching hospital, admitting civillians injured in the wartime bombing of the Royal Arsenal and caring for injured prisoners of war during the World Wars. The site finally closed in 1977 and the fine buildings appeared doomed until the designation of the Woolwich Common Conservation Area and a Grade II listing. Now, predictably, the buildings have been converted to luxury accommodation with pools, bars and tennis courts on site. A little further west, near Hornfair Park was another location dedicated to the relief of wartime suffering - this time for the animals innocently caught up in human conflict. The Old Blue Cross Cemetery was founded by the curiously anachronistically named Our Dumb Friends League in 1897. The site once also housed a bustling kennel and quarantine point for animals returning from war overseas, but this was closed by 1958 - surviving longer than the cemetery which was flattened in 1947 due to the cost of repairs. The site has recently been restored, a walled garden of surprising quiet in the midst of a busy housing estate, and work continues to uncover and interpret the memorials. The long tongue of green space leading north from here towards the Thames was once Hanging Wood, reputed to be the favoured hiding place of the highwaymen and brigands of Shooter's Hill. Today, the quiet park stretched away from my route inviting a future walk but offering no challenge as I continued on my way.

The road divided in Blackheath, the route of Watling Street contested from here on. Certainly, the southern fork, towards the Sun in the Sands then continuing as the A2 into London was a straight, direct route which resembled the traditional course of a Roman road - but the northern fork towards Greenwich seemed a more likely candidate for my walk. Driving directly ahead onto the scrubby and attractive fringes of Blackheath, the road passed over the seething concrete gully containing the Blackwall Tunnel Southern Approach Road and abruptly entered the charming village centre of Blackheath. Pleasant local shops lined the walk up to the busy junction beside the Royal Standard pub, and it was easy to see why this had become such a desirable address in recent times. I continued heading west into Vanbrugh Park, named for architect and bawdy playwright Sir John Vanbrugh who built his home, Vanbrugh Castle, nearby on Maze Hill. Initially, the streets were lined with imposing townhouses as I'd expected from an area bearing this distinguished name, but as I approached the Heath I noticed a block of low-rise, modern dwellings presenting their rather stark rear aspect to the road. Vanbrugh Park Estate was designed by Chamberlain, Powell and Bon - perhaps better known for their work at The Barbican and Golden Lane Estate in the City of London - and it was possible to see the germ of these later developments in this mix of housing types and dedication to vigorous modernism. The two-story houses which abut the Heath formed a square, looking inwards to narrow streets and walkways along the blocks. Behind these, a taller block of four distinct towers interlinked with decks and stairways rose over the houses, with distinctive corner windows giving the building the appearance of hanging from an external skeleton of concrete. Everything was separated by well-cared-for green space, and the area felt quiet and serene. Most of the homes were now privately owned - and given their heritage, much sought-after nowadays. It seemed surprising and brave to locate something so modern and incongruous on the edge of ancient Greenwich and so close to the open, and in parts still rather wild Blackheath. It seemed stranger still to cross the street and delve into an opening in the wall of Greenwich Park...

There have been recent reconsiderations of how Watling Street entered London, and the route around Greenwich in particular has been disputed. A Romano-celtic temple was discovered in Greenwich Park in 1902 and has been re-excavated in recent times to suggest it was of considerable importance. In use from around CE100 the site was very close indeed to the straight line I was attempting to strike through the park, roughly continuing the course of Watling Street which I'd walked in from Dartford. Distracted by the beautiful rose gardens and the impressive old trees, I continued uphill towards the Observatory with a growing admiration for the area. I felt like a fool in fact - I'd assiduously avoided Greenwich Park for years, once staying close to its gates but refusing to walk uphill for fear of the throng of tourists I'd seen pouring out of the gates. I'd fallen victim to an inverted snobbery which I now realised was foolish. The park was busy, the queue to visit the Observatory certainly long and tedious, but the view to the south was utterly spectacular - and entirely free of charge. Up here, gazing across the hazy and sombre shadows of the Isle of Dogs and regarding the silvery curve of the Thames I was reminded of Joseph Conrad and 'The Secret Agent' and the tale of a 'dynamiter anarchist' attempting to stop time which inspired it. The park had always been busy, always a focus of London life - of world attention no less. It made sense that Watling Street - or at least a significant branch from the road - would have passed into the park and towards the river at this near-perfect strategic viewpoint over the Thames Valley. Below me, the buildings of the Royal Naval College spread out in formal squares and courts, the sun gleaming from the Portland Stone and shimmering over the lead domes. My walk had begun in inauspicious Dartford, a place seemingly devoid of promise, and had ended here in a picture-book view of London spread out before me. I carefully picked my way down the steep path and out of the gateway into Greenwich. The sudden burst of activity felt disorienting and strange. People swirled around the tiny pattern of streets, dodging between beer gardens and street food vendors. Traffic nudged impatiently through the crowds, attempting to assert its right to dominate the old thoroughfares. Tourists ambled without apparent targets, gazing at guidebooks rather than the road at their feet. In the midst of this, the cool, dark churchyard of St. Alfege called me - Hawksmoor's most understated design perhaps, but still austere and impressive despite the lack of the octagonal west tower he planned which would have made it a southern cousin of St. George in the East. The garden felt damp, ancient and distinctly riverine under the tree canopy. It was also oddly silent despite the nearby thrum of traffic and people. This felt like the right place to end my walk.

From the platforms of Greenwich station I looked back east, the curve of tracks framing the church and the tumble of buildings which fell towards the bank of the Thames. I'd found myself here twice in recent times, and realised that during my one brief stay here I'd barely done the place justice. Despite a liking for the place, I'd often skirted around Greenwich like it was an inconvenience, ignoring the history which seeped from the ground and preferring to look north, away from the park on the hill. It had taken an ancient road to bring me here, a road walked long before the Romans and one which was almost ingrained into the land by continuous use. Somewhere between the ascent of Shooter's Hill and the descent from Greenwich Park I'd made sense of the walk and found a way to begin to read the southern geography at last. I boarded a train bound for Cannon Street where London Stone should be, but currently wasn't. I was still following the most ancient of ways...

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

From Source to Creek: Walking the River Ravensbourne

Posted in London on Saturday 7th April 2018 at 11:04pm

Anyone who regularly tolerates these missives which emerge from wanders along dusty roads or trickling minor rivers will know how quickly I can turn a pattern of walks into an altogether grander project. As a consequence, I try consciously to vary these itineraries, scattering my trips around the edges of the city in an effort to release myself from any sense of duty. Given a project, I usually collapse under the anxiety of sticking to its rules, and I vowed somewhere on the edge of Tottenham last year that I wasn't going to let that happen again. But somehow, during my last walk, I was utterly gripped by a desire to better understand the rivers which tumble out of the hills on the south-easternmost corner of London. These rivers are familiar in name, their creeks and estuaries crossed when walking the Thames Path, but I don't know them well beyond that. I lack any great knowledge of the areas where they rise, run and combine, and something of this sense of the unknown drew me back to the edge of Kent today. I'd broken my own rules before I'd walked a single step, setting out on a grey but dry morning for Bromley South via a routine familiar from my recent trip. Like last time, I managed to swiftly acquire coffee on my route through Victoria Station and stepped onto a late-arriving train which was almost immediately due to depart again for the suburbs. Soon I was curving through Brixton and Penge, weaving through the rising uplands and watching the view shift from yellow London brick to swathes of green dotted with suburban streets. It was something of a surprise to ascend from the platform at Bromley to find myself on an unexpectedly busy high street curving and falling away to the south-east. There was little time to waste exploring though, a 320 bus bound for Biggin Hill Valley was approaching the stop. This would take me to the edge of London, and to the start of my walk...

I'd never heard of Keston. This wasn't entirely surprising - it doesn't register on the rail network which is my master reference for the suburbs. It was still surprising to find a name which hasn't cropped up at all in some prior perusal of the map though, and I was curious about what I'd find out here. The bus set off south from Bromley along the A21, stopping regularly outside the pleasant villas which lined the busy arterial route out of town. Slowly, the houses dwindled on the western side of the road - Bromley Common was out there beyond the railings. I'd need to cross the common on my route back to London, and just now it felt like striking out into the unknown. It also seemed surprisingly vast from the window of the bus, with long stretches of woodland concealed by the railings and walls. After navigating the tiny knot of a village centre where the road to Croydon crossed our path we were largely out in the country. I disembarked soon after at Fishponds Road, the carriageway overhung by tall, mature trees under which blasts of traffic shuddered by, buffeting my tiny island of safety beside the Transport for London bus stop. The familiar red signpost felt distinctly odd out here - was the frequent service of near-empty double-deckers perhaps an administrative oversight? I picked my moment and carefully scuttled across the road to follow the more generous path on the other side as far as the corner where a sign indicated the entrance to Keston Common. An unmarked but well-trodden trail of crisp, yellow leaves plunged behind an abandoned block of municipal public conveniences and into the trees. I shouldered my bag and headed into the woods, grateful that the track was dry here at least. The sounds of the road were soon muffled by the foliage, and surprisingly quickly the splash of moving water replaced them entirely. A little way into the common, between the trees I saw the clouds reflected in the surface of a sizeable pond. The path wound around the outside of this pair of broad and shallow lakes, first dipping into sudden sumps of mud where the water had overtopped the bank, then climbing towards the source of the river. At the top of a short muddy clamber, in a narrow culvert, the River Ravensbourne rushed by on its journey downhill to the ponds. Up ahead a neat brick circle in a clearing was revealed, clear water bubbling busily into its centre. A father led his wellington-boot clad child stomping through the torrent, the boy squealing with delight and splashing the nascent Ravensbourne across the path. I watched this simple gleeful act of rebellion, waiting for them to return to the path to paddle through the same mud-puddles I'd encountered, before gingerly dipping a toe into the waters myself.

Almost all of the rivers I walk begin a little too far outside the urban boundary for me to track them to their sources and I'm often forced to pick them up from some convenient spot on their upper reaches where they intersect with the transport network. Today though was different, and there was a somewhat magical feeling about this spot known as Caesar's Well. Legend - at least as dictated by R.C.Hope in his 'Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England' - has it that a swooping raven directed Julius Caesar to halt his troops on their long march from their landing point in Kent to London and that here he discovered a fresh spring of healing waters. The waters became the Ravensbourne in remembrance of this fortuitous event, and the well bears the Emperor's name to this day however dubious the tale's provenance - certainly there is no record of the Roman Legions reaching this spot during Caesar's expeditions of 55-54BC. Indeed there is recent evidence that the route which the invaders took may have been further to the north, from Pegwell Bay on Thanet. This has also challenged the view that the venture was unsuccessful as Caesar left Britain with the loyalty of several Cantiaci leaders and regarded them in De Bello Gallico as the most civilised of the British tribes. To reinforce how unlikely this tale is, there is another identically named well near Wimbledon with a similar backstory but even less proximity to the invaders' trajectory. But the optimistic nomenclature is not entirely without some foundation: both of Caesar's unlikely South London watering holes occupy locations near ancient camps which were excavated in the flourishing early days of British archaeology, and the temptation to link them to the established Roman narrative would have been strong. It appears that much was inferred on the basis of legend and oral history, and in the case of the spring which lapped at my feet here on the very edge of London, it was it's proximity to the long-presumed location of Noviomagus Cantiacorum which supported the claim. The site of this bustling Roman trading town had long been sought - with speculative attempts to fix its location near Keston dating back to the 16th century. Thomas Crofton Crocker's discovery of a burial site near Keston had all but fixed the location of this much-sought-after settlement in the historical record, with the Society of Antiquaries of London convinced enough to support him in founding a dining club known as the Noviomagians in honour of his discovery. However, during the excavations prior to the construction of the abortive Ringway 3 around London in 1966, Brian Philp discovered compelling evidence of Noviomagus Cantiacorum near West Wickham. Thus there is now a far more likely location for the elusive settlement, and Keston's time in the spotlight is largely over. But Caesar's Well still bubbles with clear water, which some have been brave enough to drink. Having found the source of the River Ravensbourne though, it was time for me to set off across new territory...

Keston Common is a narrow strip of woodland, sandwiched between the widely spread arms of Keston village with the Ravensbourne forming an eastern boundary. I wasn't far from civilisation at all here, but I felt strangely isolated in the forest of bare trees. Spring hadn't reached the common yet, but the morning was warming and there was a slight haze of mist. Navigating was surprisingly tricky - when these trees were green and fulsome it would be easier to discern the pathways through the woods, but just now every gap appeared to be a potential footpath and it was necessary to follow the churned line of hoof-prints and last autumn's mulched leaf-fall to find a way through. I soon adjusted to the conditions, adopting a careful but quick trudge which allowed me to manage even the muddiest sections without slipping or sinking. A mixture of instinct and map reading kept me heading roughly north while trying wherever possible to push to the east of the common, nearer to the river's course. Occasionally, open grassy fields opened on the path and finding a suitable exit was a challenge. This was surprisingly satisfying walking - physically tougher than I'm used to out in the suburbs and mentally challenging too. The river was present but unseen - sometimes heard between the trees through an unexpected splash or the flap of a wing on water. I took a looping route, inadvertently turning back on myself to get closer to the water and crossing a minor tributary of the Ravensbourne which joined it in a deeply eroded gully, both streams still tiny but fast flowing in their natural culvert. Eventually back on route, I emerged onto the busy Croydon Road at a point where Hayes Common, Bromley Common and Keston Common met. The road disappeared into the trees in both directions, a narrow path on both sides - but just visible ahead my route continued between the trees, a narrow path heading into Padmall Wood, a more substantial tract of woodland which stretched north alongside the river. The woodland felt surprisingly wild and solitary, despite the presence of schools and impressively large homes just yards from the path. The air beneath the trees was still and beginning to get humid as the first real springlike morning of the year unfolded around the Common. I thrashed along, picking up a large stick to use as a walking aid, thrusting it into some of the muddier spots to test their viscosity and depth. In the swing of my walk now, I emerged at Barnet Wood Road, a surprisingly fast-flowing east-west rat run across the common. Thankful I didn't have to walk along this pathless channel of traffic I noted that my track was marked by seemingly pointless metal five-bar gates on each side of the road. The gates were overgrown with foliage and hadn't needed to be operated for years. Instead, the path was worn into the ground around the gates. I headed into Barnet Wood, carefully laying my large stave against the gate - I wasn't going to need that now, was I?

Barnet Wood was a little denser than the woodland I'd covered so far, extending in a narrow tongue along the course of the river while broad grassy plains opened up on the western side of the common. I decided to stick to the woods in the hope of coming upon the river again after what seemed like a long, hot walk since it last appeared. Most of the regular dog walkers and traffic clearly diverted into the open spaces here, leaving the wooded tracks less well walked and surprisingly wet and muddy - I developed a technique of anticipating these patches of deep standing water and skirting off the path via the deep mat of fallen leaves which remained dry and navigable under the trees. The persistent hazard here though was buried roots and creepers which snagged underfoot and dragged along - and it's perhaps fair to say that the large stick I'd left back at the road would have been a useful aid here. It was hard going, but the knowledge that I was closing on the river was encouraging. Then, as I was checking my direction in the anticipation that I'd soon cross paths with the elusive Ravensbourne again up ahead, I let my concentration slip. My foot snagged under a solid root anchored at each end, creating the perfect man-trap. I tumbled forward into a pile of soft leaves with a grunt of expelled breath and a very quick flush of embarrassment at my hubris. I wasn't a proper walker at all, as this entirely proved. A quick inventory of my injuries: nothing major, a scratch on the hand and a little mud on the jeans - the leaf carpet had kept me mostly clean and safe. My right big toe throbbed painfully though - driven into the end of my very solid proper walking boot and subsequently jammed hard against the branch, it had taken quite a battering. I scrambled up and tested it. I'd walk it off, like always. It hurt less when I walked in fact, and so I set off again, finally finding the busy and widening river up ahead crossing under a deeply rutted farm track. I had a choice to make here - the river ran almost equidistantly between the main road to the east, or a woodland track to the west. Following the river directly north was impossible as it disappeared into very specifically marked 'PRIVATE LAND' in Mazzard's Wood. Feeling the need to redeem my credentials after the completely unwitnessed but still somehow shameful tumble, I headed west along the track between barbed wire and electric fences. It was possible to walk in the deep, dried ruts and only encounter occasional puddles of muddy water. I skirted these carefully, often meeting the gaze of horses grazing lazily in the sunshine behind the fences. The track curved north and west, and seemed endless. Despite being alone on the path, I felt uncomfortably exposed walking this narrow strip between carefully enclosed and defended land, particularly after a long solitary trek in the woods seeing barely another soul. Finally I noted someone walking towards me up ahead and I stiffened for conflict, expecting a farmer or horseman to challenge my presence. I summoned the OS map on my 'phone, ready to defend my right to be here and desperate not to be pushed back towards the main road. In the event, the fellow-traveller nodded a brief 'good morning' and strode past me. He was no walker - dressed in white jeans with an expensive designer hoodie, a pale and pristine looking mock-fur collared parka and lots of jewellery, he seemed an unlikely character to meet on this muddy track. I was particularly amazed that he'd navigated the swampy junction I encountered a few yards ahead without incident, as I carefully picked my way along a nearly submerged plank, using the decaying and precarious uprights of a barbed-wire fence for support. Crossing slowly but safely, I turned east here to head for the Rookery Pond where the river fed a long, slender lake hidden in the woods. Now a noted Carp Fishery, this pond belonged to The Rookery, a fine house built on the fringe of the common early in the 18th century by the Chase family, and occupied from 1755 by James Norman. When Philip Norman wrote of the area in Archaeologia Cantiana in 1900, he recalled seeing the Chase Family arms above the staircase of his great-grandfather's home. The Norman family occupied The Rookery until the Second World War, when it was required for military use - finally burning down in 1946 while still in the hands of the Ministry of Defence. The land then remained open due to the newly passed Green Belt legislation until 1965, when the development of the sizeable Bromley College campus was permitted on the site. The fate of Oakley House, the other substantial nearby house on the common from the same era has been a little less dramatic, now serving as an expensive wedding venue. The Ravensbourne still marks the western boundaries of these properties, and my walk finally found it again, a fast-flowing and much larger stream now. Better yet, there was an unmapped path running alongside the river into the edge of Scrogginhall Wood - and on the basis that paths worn down by feet must go somewhere I turned north alongside the river. This was a welcome diversion - I didn't yet feel ready to head out to the busy A21 to slog into Bromley Town Centre, and this path beside the deep gully through which the river flowed was cool and quiet. My spirits lifted, I savoured this stretch of water - perhaps the last time I'd see the river outside an urban setting - even enjoying the odd experience of scrambling down a bank to splash through a stream joining the river from the west. All too soon a weed and litter choked pipe swallowed the river as it disappeared into an earth bank running along the edge of Norman Park. I crashed rather suddenly out of the bushes, a sweaty and muddy creature with a red face and wild hair, surprising dog walkers and skateboarders on the busy path nearby. Traversing the common - just a few short miles of this long walk - had felt like a trial, but was of course a less dangerous experience that in the days when Highwaymen and robbers frequently the paths and lanes hereabouts. Among the dark and often dubious tales of legend, the generally more reliable diarist John Evelyn recorded being robbed here in 1652 when assailants jumped from behind a great oak tree. It was easy to see why these strange, contested lands with their contorted paths and sudden streams blocking the way would have provided perfect cover for those who with knowledge of the ways who wanted to lose themselves. Today, for just a short time at least, I'd become one of them. But now, despite my aching toe, I was eager to continue walking.

I sat on a bench in the sunlit Church House Gardens, feeling like I was dangling my legs over a precipice onto the playground below. I'd arrived suddenly in the centre of Bromley, having trudged up the almost pristine suburbia of Hayes Road and stumbled unexpectedly on Bromley South station where my day had started just a few hours before. Suitably equipped with refreshments, I climbed the steep curve of the High Street as it led away from the valley of the Ravensbourne. I stopped briefly to admire the striking Churchill Theatre. Designed by the Borough Architect, this 1977 built block emerges from the steep wall of the valley, with lower floors being effectively underground when considered from High Street level. It felt like a building out of time, one which should probably have surfaced ten years earlier. However, it remains busy and popular, housing the main library and a range of performance spaces. It also sits in the midst of the town, pushing its sizeable concrete frontage into the flow of pedestrians scuttling between shops. Now behind me, its lower levels were reflected in a pool busy with ducks, while I gazed down into the deep gully where the Ravensbourne ran concealed beyond the margins of the park. I reflected on the changing nature of the river - from now it would mostly be snatched views from crossings and occasional bursts of foliage on littered banks. Having seen the river develop from its spring, I felt unexpectedly angry at its containment. I was surprised by Bromley though - my brief encounter with its bustling centre was unexpectedly pleasant. In trying to discover notable residents I'd noted H.G. Wells was born and educated here and expected to find a memorial of some sort, but I was disappointed to hear that the only mural had been painted out some time back. Perhaps it was his assertion that Bromley, rapidly growing towards its status as the largest London Borough during the early 20th century as a "morbid sprawl of population?" Wells later noted in a letter rejecting the Freedom of the Borough that "Bromley has not been particularly gracious to me nor I to Bromley". The list of luminaries who have lived and worked here - from Charles Darwin to David Bowie is variously celebrated throughout the town, but Wells is relegated to a blue plaque high on the wall of Primark. Few eyes drift up from the unbeatable bargains to see what it has to say about Bromley's literary son... It was tempting to linger a while longer in the warm park, especially given the dull ache which had settled into my injured foot. But time was pressing, and the walk felt somewhat longer than I'd bargained for. I set off, leaving the gardens and navigating by way of the tall Kentish Ragstone chimney of the former pumping station which towered over the low roofline of the suburbs. Nearby, at the foot of the steep slope up to town, the Ravensbourne reappeared in a deep trench surrounded by solid looking railings. I trailed it through the recreation ground which it bisected before again slipping away underground. The course though, was clear - up ahead an alleyway between the back gardens took an almost perfectly straight course alongside a raised concrete slab which concealed the waters of the Ravensbourne. In 1863, the map showed the river meandering about open fields, here - but just three decades later it had been channelled into a straight canal. Now it disappeared entirely, despite the effort to commemorate its presence in Shortlands by way of a reconstructed bridge parapet near the railway station. I leaned on the railing pondering the flowerbed below and noting that the Prime Meridian passed through this spot on its inexorable journey to the southern hemisphere. Passing motorists stared at me in a mix of curiosity and barely disguised disgust, attempting to discern what I was looking at on the other side of the structure. Perhaps it's not just H.G Wells which Bromley has chosen not to acknowledge, given the way its once proud river is mistreated by the borough just now?

Beyond Shortlands, the river resurfaces in private land. The golf course is fringed by dire warnings about trespass, so I tramped the long, straight track of the teasingly named Ravensbourne Avenue as it shadowed the railway embankment high above. At the end of the road, I pressed onward into Summerhouse Playing Fields, passing manholes with the tantalising sound of gushing water beneath them. Finally, as the swathe of green opened out ahead, the river was revealed, speedily gurgling north along the eastern edge of Beckenham Place Park. This huge park is effectively divided into two by the railway running approximately north-south, with few crossing points available. As I followed the curving course of the river, trains slowly crept between Ravensbourne and Beckenham Hill stations, pausing in the park before making their final approach. The larger, western section of the park is home to Beckenham Place, a fine manor house built on a site with a history stretching back to ownership by the Bishop of Bayeux immediately after the Norman invasion. Later, the lands appear to have been contested and divided between neighbouring manors before being united again as the estate of John Cator MP who built the current mansion. The building was inhabited by tenants for much of the 19th century, the house and land finally passing into the ownership of the London County Council, and nowadays - with boundary disputes finally settled in 1995 - the Borough of Lewisham. In the grounds the first municipal golf course in the country remains operational having served the locals since 1907. All too soon, I found myself in the north-eastern corner of the park, watching the river disappear between houses, guarded by palisade fencing. I was pushed back onto the road, and finally out onto the endless churn of the A21. Freed from the sluggish traversal of central Bromley, the traffic gained speed and thundered through the one apparently 'picturesque' hamlet of Southend. The river briefly resurfaced from its enclosed, suburban meander here, filling a sluggish, green-tinged pond which fronted a dramatically situated branch of Homebase which leaned out over the water towards an island populated with well-intentioned but odd artworks. A few brave waterfowl swam nonchalantly around the island, looking a little lost and confused. As I tried to make sense of the scene a passing drunk pushing a bike began to tell me about his shock at the sudden explosion of a recently replaced inner tube. I couldn't avoid noting his dismay, even over the relentless traffic noise. It was time to make the long march into Catford, with the river flowing just feet away between the industrial buildings of Bellingham.

Bromley Road was beginning to feel endless - a long, straight run of impressive villas giving way to parades of shops which had likely once been rather important and salubrious, but now housed decommissioned chicken takeaways and makeshift tyre and body-shops. Up ahead I could see the taller buildings of Catford approaching, not least the impressive municipal block which I'd been taken with on my walk around the South Circular. I was torn here - the river ran a little way to the west where it joined the River Pool, one of its more significant tributaries. A well-signposted 'green walk' along the Pool has been completed in recent years, which takes in the point of confluence, and it felt like an attractive idea to cut across to walk this section of river given the challenge of getting near the Ravensbourne otherwise. However, the scissor-like arrangement of railway lines which converged nearby wasn't easy to cross, and instead, I stuck with my plan to pick up the Ravensbourne again near Catford. I'd seen it on disembarking from a train here, flowing in a deep channel between the two distinct stations which sit just yards - and a few vertical feet - apart, and I was curious to encounter it again at this spot where river and rails tangled together. Beginning to feel the effects of walking in the surprisingly warm weather, I felt myself flagging as I edged around the centre of Catford and arrived at the foot of the rise where the South Circular climbs to cross the railways and the river. The road pulsed traffic from the gyratory, flowing sluggishly west towards Forest Hill - since my walk I was more aware of its tortured geography, and I was impressed that it still functioned at all under the strain. After some initial missteps I finally found the tiny roadway which snuck between the stations, passing an abandoned and decaying ground-level entrance to the elevated Catford Bridge station above, and once again crossed the Ravensbourne. The river was now a surprisingly wide and fast flowing churn of silt-brown water which emerged from under the main road and a cluster of ancient looking sewerage pipes to flow alongside the railway viaduct. Enjoying the cool and shade which the brick arches offered I headed off along the route, diverting into the recreation grounds which fringed the eastern edge of Ladywell Fields. The riverside path was busy with cyclists and dog-walkers here, the river gradually transitioning from suburb to city. Up ahead, glassy towers indicated the looming presence of Lewisham, with the ubiquitous cluster of cranes indicating the locations of ever more redevelopment. I decided to savour this part of the walk alongside the river as it passed over the railway once again by way of a spiralling bridge. I was acutely aware that there may not be much more greenery to see for a while. Across the water, the sinuous curve of the Riverside Building of University Hospital Lewisham echoed the course of the river. There is a long history of caring for the sick and unfortunate on this site, with a workhouse founded here as early as 1612. By the 19th century it was noted by The Lancet that the workhouse had essentially begun to function as a general infirmary, a role it officially gained with building on a neighbouring site in 1894. The gradual consolidation of smaller NHS units and hospitals onto the site enlarged and complicated the hospital until it was comprehensively redeveloped during the early years of this century. The hospital has struggled financially in recent years, hitting the headlines for an anticipated closure of Accident and Emergency services which resulted in protests and court injunctions. For now though, it soldiers on with its modern new buildings shimmering over the Ravensbourne, and not feeling entirely out of place.

The path rose and turned aside from the river, leaving it to head under the tangle of railway lines which converge on Lewisham. Ladywell fields had been purchased by the London County Council from the Manor in 1889, but the flooding from the Ravensbourne rendered it useless for building, leaving vacant the string of three distinct fields which make up the ragged outline of the park today. At the western edge of the park, the almost quaint buildings and covered footbridge of Ladywell station occupied the site of one of the numerous wells which gave the area its name. In 1648 a miraculous cure for a local woman's 'loathsome disease' was attributed to the waters here and the well was soon celebrated as a holy site. The site became a place of local pilgrimage with its waters offered freely to the poor and infirm: "as God hath freely bestowed His favours upon this water, so it is now dispensed gratis to any that desire it". By 1850, the well was partially covered to accommodate the coming of the railway which changed the fortunes of Ladywell considerably. Descending from the bridge into a knot of pleasant, Victorian shopfronts now occupied by delicatessens, restaurants and artisanal food stores I was struck that this was a place which was once described by a former local I was travelling with as 'a dump'. In fairness, I'd had my doubts as from the passing train it was clear that Ladywell's gentrification was well underway even then, and now the transformation appeared complete. I inadvertently shadowed a couple who were walking from café to delicatessen, gurgling infants strapped helplessly to their fronts as they meandered across the road ogling handcrafted baked goods in the store window. Inviting though Ladywell was, my business lay elsewhere and I marched steadily onward along Marsala Road and into a hinterland of fine terraced houses and oversubscribed on-street parking. This was as close as I could get to the Ravensbourne for some distance as there were few means of passing under the web of railways which flanked the western edge of Lewisham Town Centre. The cranes I had spied earlier occupied the slivers and diamonds of land between the tracks - these rough scraps of space once deemed too expensive to seriously consider as development opportunities now sprouted towers of glass and plastic cladding. I zig-zagged under railway bridges and into a development of low-rise social housing finding the river running sluggish and copper-brown at the end of the street. The regeneration had spread south along the river here to form Cornmill Gardens. This was a unusually well-used open space, part of the Rensaissance SE13 project which had seen the tired but diverse and busy Sundermead Estate unceremoniously demolished to make way for new towers of housing. The river trickled between remediated and carefully sloped green banks, a far cry from the mill stream which would have thundered through this site in times gone by. I picked my way around carefully designed benches - comfortable to perch on, but useless for a prolonged rest - and dodged wandering students with their eyes locked onto their 'phone screens. I realised that while the area felt busy with passing people, it was a purposeless zone. The locals had been tempted out by the first genuine springlike afternoon of the year, but there was little out here in the way of spectacle. Lewisham's real business took place away to the east in its complicated palimpsest of a shopping centre - built and overbuilt to suit the needs of the growing town. People here flitted aimlessly around the atrium of the new Glass Mill Leisure Centre with its Tetris-like curved flank dazzling drivers on the A20. I took a wrong turn here, accidentally heading for the station while trying to navigate by railway and river in a landscape in flux which wasn't yet fully fixed on the ground. After retracing my steps onto Loampit Vale, hemmed in between new towers and older retail parks, I was glad to turn aside leaving the centre of Lewisham and passing under the railway and into the suburbs once again. Near Elverson Road DLR station I found myself on more familiar inner-London territory: decaying but proud terraces being left until the value of their footprint increased, flytipping and out-of-date advertising campaigns on billboards. It was a welcome relief after the forced pace and painted-on smiles of Rennaisance SE13. My feet hurt - especially the one I'd damaged back on Bromley Common - and I began to wonder about successfully making it to the end of my journey. However, I was able to find the river again in Brookmill Park which provided something of an impetus. This long, slender green space slinks alongside the concrete culvert which carries the Ravensbourne, culminating in a formal garden at the rear of the Stephen Lawrence Centre. Here, a trust named for Stephen - the victim of a brutal racially motivated murder in Eltham during 1993, provides opportunities for young people. It shouldn't be a shock to see his name attached to something so absolutely positive given the efforts of his family to find justice and progress over the past twenty-five years. Even so, it was good to see it mentioned aside from the depressingly familiar context of the terrible corruption which likely still afflicts South London policing, and the racism and violence of the drug trade steered by Kentish gangsters. A name becomes a 'case' or a 'scandal' all too easily and as a result is much too easy to pass over without considering the humanity. But in this little corner near the river and the park new enterprises and young local entrepreneurs are afforded space and support from the Trust, and it felt after all that perhaps this untimely, violent death - one of too many in London's suburbs - had resulted in something positive occurring?

The Ravensbourne buckled and writhed to pass under Deptford Bridge, with the DLR viaduct sloping into the frame and closely shadowing its curves as it transitioned to become tidal Deptford Creek. The incoming tide obscured the wide expanses of muddy embankment shoring up the concrete flood barriers which enclosed the river. I crossed Deptford High Street, looking west along a range of proud facades which had once been a fine street of shops but were now largely shuttered against the relentless London-bound traffic. This was the disputed continuation of Watling Street towards the city, the true route lost under the layers of urban development, but not to the imagination it seems. I didn't linger at this rather gloomy spot, heading instead into the quiet industrial backstreet of Creekside. The river was implicit here, its course could be inferred behind yards and buildings largely via the flashes of foliage or ironwork glimpsed through gateways and between fences. The low warehouses which fringed the western edge of the street overlooked the former wharves which had lined the tidal creek, and I felt suddenly much more comfortable. This kind of interstitial zone between river and industry felt benign and familiar, and despite my growing physical discomfort I stepped up the pace, keen now to make it to the end of the Creek if possible. As I walked I considered Deptford - once a notable place in its own right, now largely an erasure between Greenwich and London. Deptford was the location of a royal dockyard opened by Henry VIII in 1513, was home for a time to John Evelyn and saw the tragic end of Christopher Marlowe - in short, a veritable Tudor-era soap opera of a location. But the recent history here is wholly of decline and obsolescence. The maritime heritage business is saturated by nearby Greenwich and the former Navy Victualling Yard can't compete with a remediated tall ship and a pop-up food market for glamour and Instagram potential. Deptford slumbered, the industrial units silent on a weekend afternoon. At the end of Creekside I took a shortcut through the misnamed Greenwich Creekside development - a jagged insertion of homes and businesses which was not yet fully operational - and not really in Greenwich. The silence between the slivers of glass and steel was interrupted only by the flapping of builders' tarpaulins and the slow grind of metal on concrete as the wind shifted the decaying gates of the only remaining warehouse on the edge of the creek. The quiet was oppressive, accompanied by a sense that permission was required to be here. I wasn't sorry to emerge on Creek Road where the Ravensbourne has been bridged since 1804. Before that time, it's likely that travellers faced a tricky crossing of the 'deep ford' which named the growing settlement, and there are speculative suggestions that a causeway is buried under the sucking mud of the banks for this purpose. Now the Creek is a boundary - both between the Boroughs of Lewisham and Greenwich and between quiet hinterland and tourist mecca. But beside the bridge, on the Greenwich bank, are reminders of the Ravensbourne's role in the development of the city. To the south, a single crane serves the last remaining on the creek, Brewer's Wharf. Operated by the Prior family since 1870, the wharf still receives aggregate deliveries from Essex for concrete production - relieving the choked roads of South London of at least a few heavy vehicles. To the north, a repurposed dock inlet hosts the banal development of New Capital Quay, which manages to look even more unreal at close quarters than the computer generated images which advertise apartments and a recently opened Waitrose. However, the ranks of identikit blocks are almost without value thanks to the discovery that they are clad in the same unsuitable material which exacerbated and expedited the spread of fire at Grenfell Tower. They stand in limbo, sold but now unsaleable - unable to undertake their role in the chain of capital and useless to those who bought them as rungs on the investment ladder. But for many, they are still home - and what a strange, liminal existence it must be. The blocks are under 24-hour guard, their future to be determined not by architects or planners, but by lawyers who argue the responsibility of mitigating the risk. Standing at the centre of the bridge over muddy Deptford Creek, looking up at the dull and somewhat benign looking buildings, it's hard to imagine an easier place to sell: Thames views, on the fringe of Historic Greenwich, near the DLR... Will the tenacious Brewers Wharf or these blighted blocks survive longest?

I padded slowly along Creek Road which gradually descended into the churn and haze of Greenwich, imagining this now quiet street lined with spectators for the London Marathon in just a few days time. Up ahead, the cluster of buildings around St. Alphege's Church shone in the unexpected late-afternoon sunshine and the ancient pattern of streets seethed with tourists. There are many points in London where transitions are made - where it is very clear that one has walked into a different zone - but few were as jarringly obvious as this one. Modern shopfronts lined the last stretch of the street as I headed for the mass of people pushing through the narrow thoroughfares of this old town. They walked, heads down, pursuing the next pre-determined point of interest and were never likely to detour towards the sluggish mouth of the Ravensbourne which ended its journey just a few yards away. I was briefly caught up in the throng, trying to find my way to the entrance of the DLR station - even that was carefully named to convince the tourists they were in the right spot: Cutty Sark for Maritime Greenwich. Missing the entrance due to the crush of bodies attempting to exit, I completed a full circuit of the busy corner glimpsing the tide of people heading for the old marooned tea clipper in its dry-dock and leading away towards the fine buildings of the Naval College. Greenwich on a sunny afternoon had its attractions, but the shuffling, jostling and impatient tourists definitely weren't part of the package. Finally finding a way into the station I descended to the platform via the stairs, cool concrete in never-ending flights which folded back on themselves relentlessly. Soon the driverless train arrived to whisk me under the Thames and into more familiar territory. Surfacing on Bow Road, the gritty and fume-filled chasm which has launched or ended so many of my ventures, it felt impossibly distant from leafy Keston, the bubbling well in the woods, and from my clumsy thrashing through Bromley Common. It had been a day marked by sudden shifts and curious comparisons. My damaged toe pulsed uncomfortably in my boot, reminding me that these tiny but revelatory excursions came at a price.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.