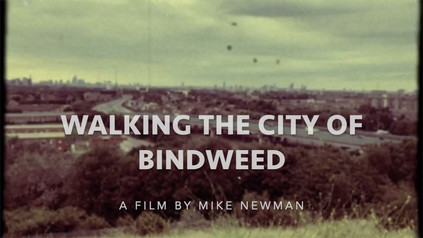

Walking anywhere in suburban England at this time of year will lead to an encounter with convolvulus arvensis - Field Bindweed. It has become the signature plant of my walks around London's periphery, and especially of the North Circular Road which during the summer months is like a white garland around the shoulders of the wheezing pollen and pollutant hazed city. I knew that this pervasive, irrepressible plant would wind its way into my writing at some point - but I was surprised to find it becoming something of an inspiration for a video project. This is marking time: a diversion where I planned to write, but messing around with shaky walker's-eye-view footage felt more productive.

So here is twelve minutes of me schlepping around the edges of the Capital, underscored by a soothing and unlicensed soundtrack and punctuated by howls of traffic, snatches of poetry and lots of strangely soporific footfalls. It's had one review of sorts from the ever precise Wizard Ho Ho himself: Iain Blair Witch Sinclair. I'll take that one, with thanks...

I still plan somehow to pull together some writing around this theme, but for now this captures the source: a series of simulated Super 8 prototypes for something far more ponderous and overheated to come.

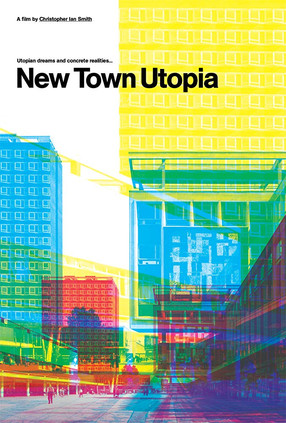

It's easy to be cynical about the history of planning in Britain, and especially easy to be scornful of those well-meaning but usually flawed efforts to build new communities which skirt neatly around the errors and problems of the past. When these developments arise - the garden city movement, the planned worker's villages of Bournville or Port Sunlight, or the Prince of Wales' village at Poundbury - they nearly always lack any kind of genus loci. In the same way, you'll often hear the New Towns which arrived in post-war Britain via a long-winded commission and various acts of parliament, lazily described as 'soul-less'. These towns were an attempt to finally eradicate the Victorian slums and to encourage people to move out of the bursting city centres where housing which hadn't been bombed out-of-use was in short supply. Like a great deal of post-war planning and architecture, they divide opinion sharply. They mixed a peculiarly British take on a socialist utopia with utilitarian simplicity and often appealed to a higher nature in their residents through the provision of arts centres, theatres and the like from the outset. But, these were consciously designed places which were still rare in a country which was struggling slowly out of the previous century with its progress hampered by two destructive wars. Provided with an unprecedented tabula rasa in greenfield sites and bomb-ravaged urban wastelands, they also deployed some of the newest styles of architecture and means of building - architecture which would have never squeezed past a fussy old planning committee in normal circumstances. This, along with the social changes which the 1970s and 80s brought to the country renders a particular image of a New Town today: concrete, streaked with rust, shuttered stores and abandoned civic pride. Is that unfair or inaccurate, or is it lazy to take this surface-dressing as a proxy for the lives of people living in these places? This film delves right into these perceptions and tests them over the course of a surprisingly human, affecting documentary.

I grew up in Redditch - a second-wave New Town, built when the cash was running out and faith in the project was waning. The Development Corporation was less ambitious than those who'd forged ahead earlier and satisfied itself with a sweep of new housing estates on the town's eastern green flank with some impressive American-style expressways to link them to the town's core. In the centre, Redditch saw the building of a new shopping centre/bus terminus combination which not only destroyed the original town centre street-pattern but mocked the locals' affections by parroting the old streets in the named 'walks' of the Kingfisher Centre. Basildon however, came earlier in the project - and was built with a greater sense of purpose and utopia it seems. It's position on open Essex land attracted industry, and numerous firms moved their plants to the new town. The future looked bright for this curious newcomer to the flat open spaces of estuarial Essex. They didn't build a railway station - people would live and work in the town, so who needed to get away? Over the course of New Town Utopia, Christopher Ian Smith meets the people who moved here, were born here and have in some cases tried to get away over the course of their lives. Many have been driven away by unemployment as local industry declined in the 80s, or have tried to follow their fortunes elsewhere - but a surprising number return. The film is built around the voices of these generations of Basildonians, their aspirations, dreams and impressions of life in the town. These are most often set against images of Basildon today: Patrick Keiller style unpeopled shots of long dual-carriageways, crumbling estates, litter-strewn footpaths. Basildon feels like a time-capsule of British idealism, a sort of mid-century sampler of design flourishes and municipal vernacular that wasn't to quite take to the mainstream. It is photogenic for the wrong reasons, impressive in its bleakness.

Throughout the film though, there is a surprising sense of something lost - something which perhaps these citizens only recently discovered they even had: a sense of being from Basildon. This unexpected attachment to the much-disliked newcomer features most strongly in two sequences: the first where locals discuss the arts scene, and the facilities which they have lost, regained and reused to continue a strong emphasis on creativity in a town which is all-too-often the uncultured and unreconstructed butt of jokes. The second occurs when the talking heads on screen consider the reputation of Basildon as a tough, violent place. There is an uncomfortable mix of dismay and pride in the reactions when they tell people they're from Basildon. But there is a concern in all of them, young or old, that the sense of being from the town is ebbing away: London draws everything in, people work in the city and sleep in Basildon. Things are changing again here, and they now have a railway station.

The film explores a further uncomfortable divide: the impact of Thatcherism on Basildon. Older residents bemoan the loss of the industries which moved with them to Basildon, which they relate specifically to the government's policies. In fairness though, the local factories (tobacco and camera film) were not publicly owned and were ill-starred already by future obsolescence perhaps? The locals also celebrate the ability to purchase their own homes and the chance to create roots in the new town. A retired trade union organiser and councillor is upset that his children don't want to vote Labour and thinks that weak unions mean weak businesses, while a middle-aged Basildonian admits with some embarrassment that the changed economy of the 1980s gave him the chances he needed to get ahead. There is a shame in seeing the positive changes in society - it just doesn't fit the idea of a worker's town which they were encouraged to support. Throughout the film, Jim Broadbent intones the words of Lewis Silkin MP, Atlee's housing minister who believed that newly created places could instil a Matthew Arnold like 'sweetness and light' in population which was not divided by class or profession, by age or race. Arts, culture and green space would be the engine of this change - and it's fair to say that from the moment the Basildon Development Corporation handed over the town to the Local Authority, it's these very things which have suffered: gradually chipped away in the interests of reduced costs and increased density.

The film concludes that while the placemaking and aspirational building of Basildon hasn't entirely worked, that Silkin was almost right: Basildon today, despite being in the overwhelmingly 'White British' band of population which stretches east of the Capital, is a placed of mixed experiences, backgrounds and outlooks. It's impossible to imagine the infectiously optimistic Hippy Joe - 'Essex' patch stitched into the groin of his dungarees - wanting to move away from the community of musicians and fans he runs a club for, but it's equally difficult to expect the current generation of young Basildonians - whether future poets and musicians, lawyers or bankers from wanting to be limited by the boundaries of this curious place. This film treats all of these voices with dignity, decency - and most importantly, it allows them the space to expand on their views without descending to soundbite and snapshot.

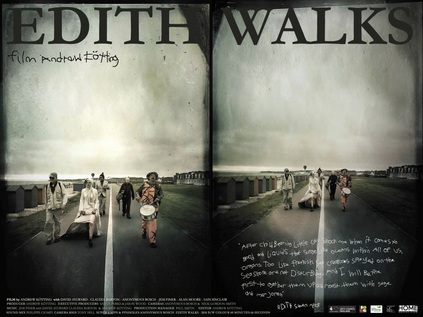

There is something rather special about one of Andrew Kötting's sometimes improbably odd film projects making it to completion, let alone a cinematic release. Getting to see one during its debut tour of British cinemas felt even more of a scoop - and I'd looked forward to this for some time. Coming at the end of a really quite troublesome and wearying week, and directly before I headed off on a summer holiday, it took on a further significance - it was, after all, a film about a journey. So we settled into the comfortable seats of Bristol's Watershed, realising that we made up a solid two-thirds of the audience. It was, almost, a private screening tonight.

Edith Walks has something in common with the majority of Andrew Kötting's previous long-form films - in that its sense of pilgrimage is almost all that holds its fragile elements together. This trek, just over 100 miles in total, attempts to create an as-the-crow-flies connection between Waltham Abbey - the last resting place of King Harold - and St. Leonards on Sea where his likeness is captured in a statue. In the sculpture, Edith Swan-Neck his handfast wife lifts the King's head tenderly from the battlefield at Hastings, recording both the moment he is discovered and that at which he is confirmed to be dead. At that moment, Harold slips from history into mythology - the story is written into every school history book, but the man slips wholly out of sight. The history goes that after Edith's discovery of the King on the field of defeat, he was segmented and parts sent to religious houses throughout the land. Finally his heart was taken to Waltham Abbey and buried. This walk, with six companions making up a clattering, chattering tribe to accompany Kötting and Claudia Barton as 'Edith', attempts to link Edith back to Harold - a reunification after 950 long years of separation - King and Queen reconnected, and man and myth made good.

The six companions are an interesting bunch in their own right - along with 'Edith', musician Jem Finer hauls a complex recording device that creates and receives sound as he walks - often the sounds provided by David Aylward, a percussionist who improvises his art marking time along the route. Pinhole photographer Anonymous Bosch captures events as they occur, while Iain Sinclair provides the closely-read mythological underpinnings for the story, sometimes bouncing his ideas against Alan Moore, the Seer of Northampton, who links deeper into the odd English Gothic. In Moore's telling, Harold never dies but becomes wholly subsumed into the myth - becoming Hereward the Wake, our first freedom fighter. Along the way, Barton sings - her remarkable torch songs providing a haunting voice for Edith which is entirely lost from the official account. As the companions progress along the Lea Valley, under the Thames at Greenwich and into Kent, their interactions with modern-day England form the narrative course of the movie. No-one quite knows what to make of them, and fewer still seem to fully understand their purpose. Such are the films that Andrew Kötting makes - miniature, absurd epics that mess endlessly with chronology, mythology and psychology in order to spin out a fable. If he has a message for the viewer it seems to be that you should believe nothing which you see, and even less of what you hear. Kötting's occasional background appearances, foolscap firmly pull onto his reassuringly solid, square head as he regards the antics of his companions are reassuring. There's someone else seeing this - it's not a dream after all.

Kötting's role in these films has always been a little unclear to me. Is he playing The Fool as a character - there to provide a foil to the incredibly erudite discussions that Iain Sinclair and Alan Moore share with 'Edith'? Or perhaps he's just there to orchestrate things - to deal with the unwelcome Police interest in Greenwich, or to corral the impossible troupe as it makes steady southbound progress? What he certainly seems to function as is a catalyst - it will be Kötting who decides to film a bow scraping at a bicycle spoke belonging to a bemused bypasser, or who instigates a conversation with Sinclair which delves into new theories and possibilities of the Harold/Hereward myth. The camera rolls, and there he is again in the background, grinning in encouragement. The architect of a particularly English sort of chaos. As Iain Sinclair has observed elsewhere, walking with others provokes story-telling and changes the dynamic of conversation. There's an almost Chaucerian element to the tales shared by the six as they progress south towards the provisional site of the battlefield, historical events represented by found footage of a 1966 school re-enactment of the battle.

The audience response to Andrew Kötting's films is often as varied, confounding and challenging as the work itself - and while I left the cinema amused and enlightened with a head full of reference points to review and research, my wife - a far more engaged cinema fan with a solid grounding in classic movies over the years - was genuinely enraged. She couldn't see a purpose beyond self-aggrandisement - but what sense was that if no-one was watching? We discussed the film and our various reactions for much of the journey home, and while her view softened somewhat she remained confused and irritated by Edith Walks and it's lack of narrative and deliberately obtuse and sometimes amateurish cinematography. For my part, I'm probably just as confused in many ways - but the playful oddness, the eccentric rewiring of history by way of a walk and the unwinding of a new mythology along the way absolutely appealed to me. Mark Kermode suggested in his own review of Edith Walks that as long as Andrew Kötting exists, all will be well for British filmmaking. It's a tough mantle to assume, and one I suspect Kötting might utterly refuse to bear - but I tend to agree that while he continues to act as documentarian and catalyst to these odd, location-specific pieces, there is much to be optimistic about after all.

Arriving at the Rio Cinema yesterday, after an overheated morning walking to Barking Creek seemed odd. It was a fairly long leap from the stink of the River Roding's outfall to this rather special old building towering above Kingsland Road and proudly defying the sweep of new towers up from Dalston Junction. I was here for a film premiére - I can confidently say the first I have ever attended in fact. Schlepping in with my rucksack and my barely concealed aroma of the road and river, I was just a little concerned that I would be straying into a foreign world where I didn't fit. However, I was greeted at the door by the equally road-weary John Rogers - filmmaker responsible for today's feature, and long-time correspondent who I'd never actually chanced to meet in person. This is perhaps even more unlikely since we've trodden a fair amount of the same paths over the years of his filmmaking and my writing about a hard-to-pin down part of London which we both seem to instinctively know is our territory.

That said, I'd never flatter myself by comparison with John as, today's film being fine testament, he has managed to work with some of the most interesting and accomplished fellow walkers of this curious and liminal path in recent times. Firstly with his London Perambulator documentary following the idiosyncratic autodidact Nick Papadimitriou around his beloved Middlesex, and now with London Overground in which Iain Sinclair and Andrew Kötting retrace and disentangle their remarkable single-day walk around the now circular Overground railway line. The book is a curious journey - starting with shared stories and walking reveries between the duo, and drifting into a dreamlike middle-section as night falls and the city darkens. The tales drift away to other people and other times, the line somehow linking them back to a shared memory of the city. Where John has succeeded is in not simply trying to reproduce this walk - instead, the territory has been retrodden in sections, sometimes with both Sinclair and Kötting - occasionally, memorably reprising his 'straw bear' act from By Our Selves - but often with other fellow travellers like Chris Petit on hand. Indeed watching Petit and Sinclair strolling through Kensal Green cemetery is like eavesdropping on the private reminiscence between two old soldiers who have trodden and retrodden the material London offers, still finding new morsels and oddities all these years later. Kötting's much more down-to-earth antics are anchors, reminding us not to take this all to seriously. A walk is still a walk, despite the shifts and subtleties we might attribute to it. Despite how seriously it affected its particpants.

Because, in fact, John's film exposes the alarming conclusion of the book as one of it's central themes. Kötting's near-fatal motorcycle accident on his former home turf as he leaves London after the walk is as much the start as the end - the walk is a journey through his opiated memory, troubled by the recalled insertions of Sinclair's own history. As the damaged motorcyclist sleeps through his trauma, he rewalks and relives the circle of the Overground. The film moves fluidly through these dreamlike shifts between scenes and conversations and thus avoids being a mere documentary of a walk around a changing, disappearing London. Sinclair is candid and thoughtful throughout - able to talk with authority but little certainty about the last London - the city's end-stage as it moves into a post-post-Thatcherite era of offshore ownership and privatisation of land, air and water. His gentle tones and careful prose are pitched perfectly alongside John's camera work which is happy to linger on a curious railing or brick while the author speaks - a touch of Patrick Keiller in uncharacteristic close-up perhaps? Memorable too, are the scenes where Sinclair reads from the book to the accompaniment of local activist/solicitor Bill Parry-Davies' saxophone. These moments link Sinclair back to the beat poets he writes so effectively of in American Smoke - and to their own perhaps unexpected connections to the Overground railway too.

This cut of the film was edited specifically for this launch at the East End Film Festival, and there is every chance that by the time it sees another viewing it will include different scenes from the vast archive of footage which John built up on the walks and interviews he conducted. This is a good reason to seek out London Overground if you see it playing - it will be, a little like the railway which anchors it's existence - a changing and ever-surprising circuit.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.