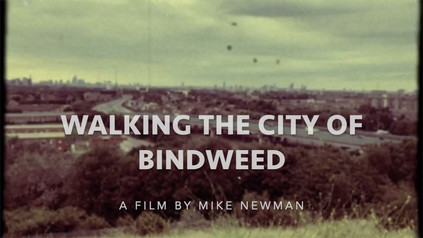

Walking anywhere in suburban England at this time of year will lead to an encounter with convolvulus arvensis - Field Bindweed. It has become the signature plant of my walks around London's periphery, and especially of the North Circular Road which during the summer months is like a white garland around the shoulders of the wheezing pollen and pollutant hazed city. I knew that this pervasive, irrepressible plant would wind its way into my writing at some point - but I was surprised to find it becoming something of an inspiration for a video project. This is marking time: a diversion where I planned to write, but messing around with shaky walker's-eye-view footage felt more productive.

So here is twelve minutes of me schlepping around the edges of the Capital, underscored by a soothing and unlicensed soundtrack and punctuated by howls of traffic, snatches of poetry and lots of strangely soporific footfalls. It's had one review of sorts from the ever precise Wizard Ho Ho himself: Iain Blair Witch Sinclair. I'll take that one, with thanks...

I still plan somehow to pull together some writing around this theme, but for now this captures the source: a series of simulated Super 8 prototypes for something far more ponderous and overheated to come.

The East Bank: Walking the Antihistamine Trail

Posted in London on Saturday 6th July 2019 at 11:07pm

The train doors clattered open, and I stepped onto the platform of what felt like an old, rural station which long predated the electric Underground train I'd arrived on. I was the only passenger to alight, all interest apparently being focused on city-bound trains on this pleasant summer morning. It had been a long, hot ride out from the stuccoed villas of Lancaster Gate where I'd descended into the earth.

Less than twenty miles away from Bethnal Green, the automatic doors of the tube train open onto the land of Greenleigh. On one side of the railway are cows at pasture, on the other the new housing estate.Family and Kinship in East London, Michael Young & Peter Wilmott, 1957

Alighting at Debden felt like a return to more innocent age of these walks: when I'd first ventured along the valley of the River Roding, it felt like something of a revelation. I'd been straying further afield for some time, worrying the greener edges of London - but that walk truly took me out of my comfort zone, and reminded me what my walking boots were really for. At the end of that summer day, drenched by an unexpected downpour in Ilford, I knew my horizons had expanded. Yet again I'd strayed outside the self-imposed cordon, pressed against the membrane of anxiety which the edge of the map always offered. Today, the valley was dry and hazy, the intermittent summer having returned in the week or so before my walk, frazzling the grasses and drying the earth underfoot. I started out with a quick trip for provisions which involved a detour into Debden's Broadway - a wide boulevard between terraces of shops and maisonettes opened in 1958. Debden was Young and Wilmott's 'Greenleigh', and when the shops of the Broadway finally opened for business, the earliest parts of the London County Council estate in Debden had already been in existence for a decade. This suburban extension which almost joined Loughton to Theydon Bois was largely unwanted when first mooted between the wars, not least by locals who feared overdevelopment of their relatively rural surroundings. Housing between the two villages was initially proposed under the powers granted to the LCC by the Housing Act 1919, but work did not commence until after the Second World War in 1945 by which time the need was greater than ever: the densely populated East End had been pulverised by enemy bombing, and the population had already begun to scatter into the edges of Essex. The acquisition of land near the Roding at Oakwood Hill for prefabricated homes was the beginning of a much larger development which would see the estate spread north and east, crossing Chigwell Lane and finally stretching along the western side of the railway. Expediency and cost meant that a number of prefabrication and building systems were employed, and for all the talk of a warren of identical houses, the estate remains in fact a mixture of interesting and novel styles of home from the Laing Easi-form to the Cornish Unit. For the locals though this was no succour: the trade between necessity and the destruction of the Essex countryside was hard to balance. Donald Gillingham, the hyper-local naturalist who rarely roamed more than a few miles from his home in the Roding Valley wrote of these times:

The war was not over. A new invasion had begun - all the more tragic because, perhaps, necessary. It had begun insidiously when surveyors went out like a fifth column and drove in red and yellow stakes.Unto The Fields - Donald Gillingham, 1955

Tensions rose further when it became clear that the LCC estate would primarily house displaced Londoners: either those bombed out of their homes, or others decanted to allow clearance of urban slums. There would be few homes in Debden for the local families in Loughton, which too was growing into a sizeable town. Instead, those locals seeking properties would likely be offered tenancies in Essex County Council's own Harlow New Town some ten miles to the north. With the identity of this growing suburb contested and the links to Loughton and Essex now tenuous at best, the question of a name for the area was equally fraught with local politics. The issue was settled in 1949 when the Great Eastern Railway's Chigwell Lane station became London Underground's Debden Station on the newly electrified extension of the Central Line. The name, drawn from the nearby hamlet of Debden Green, paid ancient homage to the valley of the Roding which the estate bordered. But there is no escaping, even today, the sense that this is a little bit of London outside its boundaries. The bright red buses turning at the end of the Broadway, the clatter of the Central Line trains heading for the distant city and the hum of the M11 all draw the ear and the eye south and west. I was going to follow the same line today, for a little while at least.

I retraced my steps, heading under the railway bridge towards the Motorway and knowing that I'd soon be leaving the urban fringe behind for a while. The familiar gateway to the green path along the river was a welcome sight, and once again I experienced the sense of plunging into the countryside despite walking a narrow margin between road and railway. The cracked asphalt of the path had deteriorated over the previous two years, grass and weed pressing up through the untended surface. Tall thistles and an impressive crop of nettles swayed beside the path, almost hiding the busy trickle of the river from view. Insects flitted across my path, the drone of the M11 almost hidden by the constant buzz of life in the grasses. When I'd been here before I'd hesitated: this felt too far off the beaten track, too unlike my preconceptions of the urban rivers of London. But I'd persisted in walking the meanders, sticking to the paths which were vague then and even harder to discern today as the grass had converted alternate weeks of rain and sun into spurts of furious growth. The reward was the surprising peace of the Roding Valley and it was good to be back. I was determined though, to walk the eastern bank as far as I could today: last time, this had eluded me. The one crossing point I'd planned to take was blocked by a locked entrance gate, and I'd found myself confined to the western side of the river and a number of circuitous diversions from the bank. So at the first opportunity, the Charlie Moules Bridge, I made my crossing. The bridge, built in the 1950s following a campaign by Councillor Moules to link the recently acquired meadows in Chigwell with the band of development along the western side of the river, delivered me into silent grassland. The barely visible path was a worn groove leading into the treeline ahead while clouds brooded over Essex to the east. I wondered if I would once again find my progress halted by a storm? Reflecting on my first visit, I suspected the sight of these remote, quiet meadow paths would have sent me scurrying back to the relatively civilised western bank - but today it was perfect. Barely more than a trail through the ribbon of woodland on this side of the river, the tree cover occasionally left sheltered patches of the path surprisingly muddy underfoot. I saw and heard no-one until the path came alongside the fishing lakes and the distant, low voices of anglers comparing catches could be heard over the river. A little way ahead, I was faced with a decision - both forks of which led to a diversion. I could head west and retrace my route from last time, or turn east and edge around the David Lloyd leisure centre and the extensive grounds of the Guru Gobind Singh Khalsa College complex. The river was off-limits, for a brief stretch at least - so I struck out east, seeking novelty. The diversion was no shorter than the western option, taking in a snaking access road around the school and the gym, finally coming alongside the sliproads for the unbuilt Chigwell Motorway Services. Provision had been made for this site when it was intended to continue the M11 deeper into London. In the event, with the motorway griding to a suburban halt at the North Circular, a service area here had never attracted the interest of operators and the two wide loops of road encircled rarely visited oases of green space, linked by a disused subway. For a brief spell prior to the 2012 Olympics, the southbound island had served as a temporary logistics base for DHL, but they had not taken the option of a permanent lease and the site had returned swiftly to nature. Finally, the long access road decanted me onto Roding Lane, the buzz of traffic unfamiliar after the quiet of the wooded riverbank. I knew the way here: west along the edge of the cricket ground where I'd struggled to escape before, the road briefly rising towards Buckhurst Hill. I turned aside as soon as I could, heading back to the river along the path beside the allotments near The Cascades. Feeling like a seasoned veteran of the Roding Valley, I was soon beside the water again.

My aim now was to return to the eastern bank as soon as possible. I knew that the path along the western side of the river was tricky to follow, and given my greater confidence and experience now, I figured it was worth trying to stay the eastern course. I found my opportunity immediately after passing under the impressive brick viaduct carrying the Hainault Loop of the Central line, near the lesser used Roding Valley station. This cool, quiet spot remained a favourite for taggers and more creative street artists alike and I admired their work briefly before crossing the river onto a largely uncharted path. I was soon plunged into deep grass and tall swaying heads of cow parsley. There was really no path here at all - perhaps just the merest suggestion of a depression in the sea of green ahead of me. I pressed on, kicking up a cloud of pollen which I knew would cause me issues later. To my left, the boundary of a new development on the site of the former Tottenham Hotspur training ground snaked along the ridge of the valley. The housing here was part of the planning gain supporting the impressive Anderson Foundation school for children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder which occupied the site of the former training centre after the team's move to a purpose-built facility in Enfield in 2014. Pushing on further south, my makeshift path bordered a scrubby, wooded wasteland which had for almost a century provided the well-heeled Epping Forest District Council with a site for disposing of its detritus. Since the 1920s, parts of the site had provided a landfill dump, and a sizeable sewage works left strange concrete hardstandings amidst the trees and scrub. This was, strictly speaking, Metropolitan Green Belt land - but the presence of the final stretches of the motorway, and the permitted encroachment for school and housing gave it a distinct edgeland feel. I was walking the transition line here: wading through armpit deep grass and foliage, guessing at the path onwards and feeling incredibly remote from the playing fields and parkland on the western side of the river. Beneath me, the Roding snaked onwards towards the Thames, the path occasionally coming precariously close the edge of the gully which the river had worn over thousands of years of frequent flooding. I ignored the catch of hayfever in my throat and the irritation developing around my eyes: I'd walked plenty of trails in the past named for ephemeral flowers and natural features along their route, but as the only person foolish enough to tread this path today, I claimed the naming rights - this was The Antihistamine Trail.

Rather unexpectedly the path widened and developed a stony surface, the mark of adoption by the local authority. The Roding Valley Way had reached this far along the east bank at least, and I soon found myself contemplating the other end of a bridge which had been securely locked out-of-bounds on my last visit despite being signposted towards the sometimes poorly marked footpath along the riverbank. I recalled sitting in the park on the other bank, applying sunscreen and recalculating a route which would take me the entire length of Ray Park before getting back to the river at Snakes Lane. This time I was able to follow the path I'd originally planned which from here to Chigwell Road was surfaced well enough that I passed someone pushing a pram in the humid air of the early afternoon. To the east, the baleful water tower of the former Claybury Asylum glowered over the treetops. Yet again, my walks began to entwine themselves into a network of knowledge: always selective, and sometimes false. The territory slowly gave up secrets and allowed me to link things together, my own travels dissolving into others' mythologies. The thin tongue of land between the river and the motorway dwindled to a narrow point, hemmed in by the built-up edges of Woodford encroaching from the west, and I was unceremoniously decanted onto the edge of the busy A113 as traffic hurtled under the motorway. I made the crossing with care, noting how alien traffic felt after the quiet isolation of the riverbank. I wasn't sorry to plunge back into the long grass for one last relatively wild stretch along the edge of the M11 as its carriageways began to divide to accommodate a ghost interchange. Here, the road would have ploughed on towards Islington, soaring over the North Circular and carving into the suburbs - but of course things didn't go quite to plan, leaving the motorway beached on the edge of the city. I soon found myself at my own junction: I could cross a narrow bridge to the west and find myself at a very familiar filling station, or turn east and walk an even better-trodden path between the motorway viaducts. I headed under the shadows of the concrete stilts - this was a special place, familiar from several walks which all seemed to converge on this dusty underpass. Walking among the huge, grey piers of the bridge felt like meeting old friends unexpectedly, and despite a pang of regret at leaving the river and the rough, challenging walk which had tested my resolve to get here, I was glad to be back on well-worn routes.

I've written several times before about the stretch of footpath which curves alongside the North Circular as it turns south towards the river. It was the closest I could walk when I was shadowing the broad, elevated road, upgraded to cope with the traffic spilling off the incomplete M11. It was also the path I'd taken when I'd walked along the Roding, and I realised now how deceptive it was. The gully of green-shaded water and the ranks of pylons which stalked the banks were corralled into a remarkably narrow strip of wasteland which was barely wide enough for the river and road, Indeed, it only accommodates them due to artificial straightening of the meanders in the course. I stepped up my pace, glad to have a good surface and childishly content to be kicking up clouds of Essex dust over my boots as I trudged onwards. I spied a familiar sight - a three-cornered pylon which shivered with multiple high-tension lines. It was strange and monolithic, standing in the deserted river valley largely unregarded by humankind despite their dependency on its steely purpose. The pylons here, like those which marched along the Lea Valley, felt like fellow travellers. They were ever-present, always more numerous than other walkers, and often felt far less threatening. I passed under the North Circular via the broad concrete subway which led to Redbridge Roundabout. I needed to detour here, passing under the angles of the junction to resurface on the south side of the A12 and double back. Rather sentimentally, I checked the short entrance road to Wanstead Pumping Station to see if the cat I'd met here a while back was still resident. If he was, he was sensibly sleeping in the cool shade somewhere in the overgrown garden of the lodge. I pressed on, turning aside in the backstreets of suburban Wanstead. Instead of my usual route to Ilford via the filthy litter-strewn backstreets beside the A406, today my aim was to head into Wanstead Park. The history of this substantial green space, now administered as part of Epping Forest by the City of London Corporation, is not entirely a happy one. A manor at Wanstead is recorded in the Domesday Book, and at the time of its acquisition by Sir Richard Child in 1703 a sizable house already stood on the site. Not imposing enough it seems for Child, who then set about building one of the first great mansions in the Palladian style to be seen in Britain which was completed by 1722. With Child created Viscount Castlemaine and married to Dorothy Glynne, heir to the Tylney family lands and fortunes, the impressive colonnade of Wanstead House provided a fitting seat for the now influential family. The inheritance of the Tylney properties was conditional on Child changing his family name, for which he obtained an act of Parliament in 1734. This set in chain a series of events which left, via generations without issue and the torturous laws of inheritance and title, the entire fortune in the hands of Catherine Tylney-Long. As the richest unmarried woman in the land, it is perhaps unsurprising that she was courted by the dissolute and caddish William Wellesley-Pole, nephew of the Duke of Wellington and already a notorious character.

Catherine accepted his proposal, and to suit the conditions of inheritance Pole sought a royal license to change his name again, becoming the faintly ridiculous William Pole-Tylney-Long-Wellesley. He was thus elected to Parliament for St. Ives, and then for Wiltshire where the Tylney name remained influential. As an MP he was noted primarily for his extravagance rather than any great political acumen, and in 1814, Pole hosted an impossibly flamboyant fête at Wanstead House to celebrate Wellington's victory over Napoleon. The event was attended by numerous royals, including the Prince Regent and marked a high point in the houses' fortunes. The property and lands were held in a complex trust to protect the inheritance of Catherine's heirs, against which Pole raised an unwise mortgage to pay his spiralling debts. In 1822, the trustees stepped in to secure the situation - and with the land protected from sale for 1000 years, they liquidated every possible asset instead, auctioning the couple's personal property, demolishing Wanstead House and selling-off the building materials for a fraction of the cost of raising the great house. Catherine died from an intestinal complaint in 1825 having been abandoned by her husband, though letters to her sisters imply that her illness may have arisen from a venereal disease he had passed to her. Meanwhile, Pole remarried and returned to Parliament, though his second marriage was little more successful than his first. He continued to do his utmost to avoid accounting to his creditors, particularly seeking the custody of his son William with whom Catherine's remaining estate would rest. His uncle, the Duke of Wellington mounted a furious defence to prevent this, and Pole's petition was denied by the Court of Chancery. In contempt of court, Pole found himself committed briefly to the Fleet Prison. Retaining an interest in the estate until 1840, Pole oversaw the removal of many trees and destruction of original features of the gardens in an attempt to raise further funds, but he was finally prevented from further interference via a court injunction. The grounds of the house thus passed through the Wellesley line, with a portion sold to the Corporation of London in 1880. Wanstead Park subsequently opened in 1882, and has remained largely unaltered with the retention of remnants of the formal gardens designed by George London and improved by Humphrey Repton. In particular, I wanted to find the Grotto. Completed around 1760, this structure beside the ornamental waters in the grounds was not entirely a folly, providing a boathouse and repair facilities with a small lodge for the keeper. The building was decorated with shells, crystal, and mirrors under a domed ceiling which allowed in light from above. When the park opened to the public in 1882, tours could be arranged with the keeper - a Mr Puffem - and these were popular enough that the man received the honour of a humourous portrait in Punch magazine. In 1884 a fire, caused by overheating tar being used to repair a boat largely destroyed the grotto leaving only the facade standing. The structure was made safe and retained as a ruin, the bridge which formerly linked it to the eastern side of the water long since gone. Now the grotto sits safely behind a palisade fence, designed to prevent the inevitable insurance claim from someone clambering inexpertly over its ageing stonework. The lower area where boats could dock was uncovered by MoLAS archaeologists in 1998 but the structure was then left undisturbed behind its protective fence for some years, with vegetation soon taking hold and obscuring the remains from view. In 2011, a clearance operation revealed the grotto once again.

I explored the area around the Grotto for a while, enjoying being the only person around as the cloud finally passed over and illuminated the dried-up reed beds of the ornamental waterway. My route out of the park took me across the swaying grasses, aiming for a crossing between the Heronry Pond and the Perch Pond near a busy café. The earlier pollen exposure had begun to take its toll, and an oppressive headache was descending. I decided to tough it out for a while in the hope that I wouldn't have to cut short my plans. The next stretch would take me back onto the streets, among far more people than I'd seen all day and the thought wasn't welcome just now. I resisted the urge to remain in the park and to seek out the other hidden treasures which remained from Wanstead's spell as the centre of London society. Eventually, though I had to leave, taking the long, hot slog along sleepy Wanstead Park Avenue which led me to the eastern edge of Wanstead Flats. It was good to see the Flats recovering from the fire last summer, and from the brief walk alongside them, I could see foliage and insect life aplenty. Nature finds its way, it seems. I passed the impressive gatehouse of the City of London Cemetery where I took the southern fork in the road towards Manor Park, the route lined by mature trees and feeling rather cut-off from its urban surroundings. The remained of my walk would be a continuation of this route, often crossing my previous paths as I headed directly towards the Thames. Epping Forest finally gave way to London near Manor Park Station, sleepy in the afternoon heat as it faced the last tree-lined edge of the ancient woodland. A little further on I crossed Romford Road, a route I'd walked at the end of last year in a surprisingly memorable east-west perambulation. It was a shock to suddenly be surrounded by people again as I waited for the lights at the busy crossing. On the south-western corner of the crossroads, the grand brick and stone Earl of Essex with its imposing corner-turret remained empty and awaiting its conversion into the inevitable luxury dwellings, following a battle to retain it as an asset of community value. Beyond the crossroads, my route continued as High Street North, forming the spine along which the drawn-out town of East Ham spread its busy centre.

East Ham can claim origins in the Saxon settlement of Hamme which roughly constituted the dry land between Bow Creek and Barking Creek. Recorded as early as 958, the area was neither populous nor prosperous for the following nine centuries or so, presenting a marshy and inaccessible face to London. Transport thus defined modern East Ham - Victoria Dock opened in 1855 and the railway arrived in 1859. While in 1863 the area was still described as a 'scattered village' the following decades saw rapid urbanisation. As with other districts in the East End, the area was never affluent and the population largely worked in the docks or industry nearby. The pattern of terraced streets fanning out across the marshes remains familiar today, though the demographics have shifted dramatically. A County Borough since 1915 despite the protestations of Essex County Council, East Ham was absorbed into the London Borough of Newham in 1965, but by then was already a busy town centre in its own right. The area had weathered tremendous upheaval in its short tenure as a unit of government - relentless wartime bombing, rising poverty following deindustrialisation and the closure of the docks, and the tensions arising from successive waves of immigration. My walk along the High Street - on the face of it, not unlike any small British town centre - surprisingly reflected all of this history. Firstly, the mix of shops was a clear marker of the demographics: Halal butchers and fried chicken shops rubbed shoulders with Polish supermarkets and traditional Kosher stores. The street was still busy with traffic here, and the narrow pavements were a challenge to navigate, as I weaved dizzily between family groups stretched across the path, children lagging at the end of the line and teenagers texting furiously a few steps behind. The bright afternoon was charged with an urban energy and enriched with the smells of competing cuisines. I couldn't pass through quickly, even if I'd wanted to - the sheer press of people prevented it. South of East Ham Station, opened by the London Tilbury & Southend Railway in 1868, and served by the District Railway since 1905, the street is partly-pedestrianised and the local stores jostled for attention with branches of national outlets. Later in-fill development is evident here, corresponding chillingly with the sites on which high-explosive bombs fell. Proximity to the docks clearly drew the enemy closer here, and the curious mix of Victorian and modern was jarring when I cast my eyes above the shopfronts. Avoiding this part of town, the traffic took a spin to the west along Ron Leighton Way, named for the Labour MP for North East Newham who served from 1979 until his death in 1994, and who was a notable Eurosceptic .

But these former marshy flatlands are home to others too: the dead cluster around East Ham. The old Jewish burial ground at Plashet was opened by the United Synagogue in 1896, and despite being closed for burials now sits just a narrow terrace of buildings away from the busy High Street. Further south, the vast East Ham Jewish Cemetery of 1919 was still operational, tucked away between the High Street and the line of the Northern Outfall Sewer. As London crept out across the marshes to the east, so new plots were needed for living and dead alike, and the alien east with its air and reputation already regarded as unwholesome had to carry the burden. Much of East Ham's heydey coincided with a golden age of municipalism, and the pride in the new Borough was reflected in the vast and ornate Town Hall completed in 1903 and still standing proudly at the crossing of High Street and Barking Road. The buildings ceased to be Council offices when the borough decamped to the Royal Docks, exchanging Edwardian brick for a huge glass-sided hangar overlooking London City Airport. While the Town Hall was being built and subsequently extended, the Borough was taking an enlightened approach to further new duties: appointing a permanent Fire Brigade, building new schools and dabbling in public housing. I paused to rest my aching feet and weary head at the corner of Central Park, a result of the early policy of the newly independent District to provide green spaces in each of its four wards. The grounds of Rancliffe House were acquired in 1896 for the laying out of a public park. Opened in 1898, the house was demolished a decade later and the park expanded to include an open-air swimming pool. The garden and art-deco Fist World War memorial at the corner entrance where I was seated followed in 1920, with the pool closing for good in 1923. Today, the circle of benches around the memorial was home to an extensive and expressive school of drinkers. As I stopped for refreshments and antihistamines I realised I'd strayed into someone else's drama: insults had been traded between benches, and tensions were rising. No-one seemed inclined or perhaps sober enough to make the first move, but catching the eye of an apparently uninvolved older drinker with a ruby-red nose and sad, drooping eyes, we tacitly agreed it was time to leave. He shambled off into the park, defying fences erected to safeguard the setting-up of an event, while I returned to the High Street. As I passed through the entrance gate, a proud survival from the earliest days of the park I heard the crash of glass and the yelp of pain which suggested that someone had finally managed to get their act together behind me. I didn't look back.

I was nearing the end of my walk now, but I didn't appreciate quite how suddenly it would come upon me. A consequence of the walking the arterial routes in this part of London is that while I appreciate how far things lie from the City, I often fail to appreciate their relative proximity to each other. Looking up I was surprised to see a sign advertising the junction with the A13 at Beckton Alp. I'd passed this way several times, and knew this junction well from other angles, usually arriving at the end of a long walk from elsewhere. I was nearing a spot I considered almost sacred on my walks, but I hadn't realised that this spot had a much longer history of worship. Tucked into a wooded corner where East Ham dissolved into the scrappy retail-park edges of Beckton stood St. Mary Magdalene Church, extant since around 1130 and built from stone including fragments of far older Roman remains. The low tower, a 13th century addition, was masked by ancient trees which clambered around the stones of a mossy, dark graveyard. It felt out-of-place here at the careening junction of major roads. Annexed to the church was East Ham Nature Reserve, an extension to the churchyard which made it one of the largest in London, and now a wilderness-like environment. Under the tangle of trees and through the bramble bushes, all appeared calm, green and humid. The fringes of the site had seen some speculative fly-tipping or drifting roadside rubbish but deeper into the plot the litter petered out. I stared deeper into the woodland, surprised by the sight of an old memorial at a queer angle. As I looked longer, more appeared: moss-covered and weather-worn, these old stones bucked from the ground in unsettling ways which suggested recent upheaval. I turned to check I was still on the busy road, with traffic queuing to swing out to coastal Essex or into London. It was, reassuringly or not given the strangeness of the times, still 2019 out here on the edge of Beckton. Somewhere ahead of me though, in an unmarked grave, lay William Stukeley, an antiquary and archaeologist who had made surveys of sites such as Stonehenge, Avebury and Rollright during the eighteenth century, largely founding the modern archaeological method. Stukeley's career was long and varied, taking in medicine and service as a clergyman, and his tendency to seek theories which placed ancient monuments and fossils in a Christian tradition as he grew older assured a devaluing of his work in later centuries. However, it's likely that Stukeley's annual expeditions on horseback to record these sites, and his evident zeal in discussing their history in eminent company has resulted in many of them surviving until now. His earlier research drew greatly on speculative ideas about Druidism and Egyptology, giving his work an almost mystical quality. Indeed it was hard not recall his description of Rollright Stones as I gazed across the gnarled trees of his resting place:

...a very noble, rustic, sight which could strike an odd terror upon the spectatorsWilliam Stukeley, an eighteenth-century antiquary - Stuart Piggott, 1950

I crossed the slip-road of the A13 and passed under its thundering concrete carriageways, emerging on the relatively quiet road into Beckton. Above me, the green flanks of Beckton Alp glowered over the flat marshland which was slowly disappearing under new development. It was impossible not to be drawn through the gateway, and to start the zig-zag climb to the peak. I wasn't alone today - it was a glorious afternoon with clear views across the estuary, and a group of young women had ascended just before me. I found the old gap in the fence mended, but a new opening had been twisted into the palisade nearby. It was a tighter squeeze, but I managed it without losing too much dignity and soon found my way to the peak. The group of youngsters lounged, laughing and chattered in the artificial bowl at the top of the hill, entirely ignoring me as I wandered the edge of the peak taking in the views. London unfolded: the city hazy and indistinct in the near distance. The dark ribbon of the A13 snaked back towards the city - walked, written and re-written but still somehow holding my attention. It was easy to understand Stukeley's instinct to romanticize and mythologise his findings from this vantage: while I'd made no novel discoveries on my climbs up here, I'd certainly found solace and sometimes unexpected resolution in the sweep of views and churn of winds. The view changed subtly as the sun shifted and clouds formed and drifted. Time seemed to slow. The regular pattern of terraces and patches of green parkland stretching away the foot of the hill signified the territory I'd just walked. I looked north, the tower at Claybury was just visible and beyond it a smudge of dark green signalled the distant forest and the valley which I'd navigated to reach this spot. Only the giggling and excited chatter behind me reminded me that I was still anchored to the vast sprawl of a city between me and the towers in the west. That the city could still surprise, delight and inspire me wasn't in doubt at all. Being back here, arriving from a different direction and viewing it in fresh context felt like a reward for the miles I'd covered. I started my descent to the DLR station, eager to make sense of today in writing.

You can find more pictures from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.