The day had a strangely unsettling start. Despite having very little time in their presence nowadays, as ever First Great Western have done their best to make things complicated. Today it's a lack of hot food, no working toilets and the promise of a 45 minute delay east of Reading. As it goes, the delay was resolved long before we got to that end of the line, and despite a little leg-crossing the journey was mostly relaxing. The slight frisson of uncertainty persisted at Paddington though - it was curiously busy, there were queues everywhere, and getting around the place was frustratingly slow. I finally found a quick, less than optimal breakfast, recharged my Oyster card and headed gratefully for the Hammersmith & City Line. On reflection, I think I was just eager to get moving - and rather surprisingly I felt a little nervous about the walk. I recalled how trips east of the city would sometimes feel strange and disconnected, how I felt like I was pushing at an invisible frontier. I also recalled that it was probably that very feeling which had kept me coming back for many, many years. In any case, I had a very loose plan and so far, the misty morning weather was mostly on my side. It was time to press on.

I surfaced at Aldgate, the city rising out of the mist to my right. I immediately turned my back on it - the lure of coffee and comfort was strong just now, but I'd planned at least the first part of my day and would inevitably berate myself if I didn't see it through. A few steps to the bus stop and onto a No.15 headed for Blackwall. We lurched into the traffic and turned onto Commercial Road. I'd walked parts of this route before - but my travels had criss-crossed the street rather than tracing it's path. This was, then, a rare pleasure - to take in this long eastern byway in relative comfort. The street is a weird mixture of bustle and decay, like much of the inner East End. A tumble of chicken shops, travel agents and dubious colleges give way to little gems of history, like the majestic Troxy - rescued from the inevitable fate of all such buildings - a Bingo Hall. Finally I found myself on more familiar ground in Limehouse, passing the former Town Hall and the grim white flank of Hawksmoor's St. Anne, before plunging into side-roads and emerging on Poplar High Street. Alert to needing to alight somewhere around here I let my instincts take over, and on sighting a Tesco Metro I hopped off the bus. It's strange - logically I know I'm in the midst of one of the biggest conurbations in the world and never far from food and drink, but something about these walks into the unknown makes me feel the need to stock up. Never wishing to be caught without the means of sustaining myself, I bought a few items and turned the corner onto the road as yet unwalked...

The meeting of ways here is a stark lesson in how planning can make life difficult. Passing the brutalist blocks of Robin Hood Gardens, still standing despite renewed efforts to progress their removal, I wandered into a complex mess of subways and paths which cut under and around a roundabout. High above, the Dockland's Light Railway crossed on a surprisingly elegant viaduct considering the heavy-handed nature of the buildings here. Looking up from this modern-day amphitheatre, all was concrete and glass. Cranes towered to the east, more dockland infill arriving soon - and to the west, the shining fascias of Canary Wharf reflected grey sky back at me. The tops of the towers were lost in low cloud, the pyramid atop One Canada Square coruscating as heat escaped from it's complicated internal systems. I wound around the roadway, rising south of the tracks with the former wall of Poplar Dock separating me from a classy marina development. I turned east, crossing the quiet street and delving into a mess of new buildings - half-finished mid-range hotels curved around a residential site nestled between the air intakes of the Blackwall Tunnel and a rank of earlier, dated looking housing developments from the first wave of Docklands development. I followed the road as it curved to run alongside Aspen Way, the arterial which delves under the remains of East India Dock in a nearby tunnel. Squeezed against the road and the DLR, at East India station I turned towards the River looking for open ground - more by instinct than plan - and found myself walking a long, straight avenue of trees with a metal line inlaid into the paving. A glance at the street sign explained things - Prime Meridian Walk. Looking beyond the avenue, I saw the ribbon of silver river, and almost floating above it, the bulge of the O2 in North Greenwich. I walked the line south, local and prime merdian converging at a gushing outfall of dubious aroma, the river shrouded and still. Cable cars edged along the wire to the east, while the baleful hulks in Docklands glowered from the west. It was here that I noticed for the first time that in a city of a rough eight-million or so, I was entirely alone.

It was a feeling which persisted for much of my walk in fact. I spend far, far less time alone now than I have for a very long time, and it was suddenly - almost pressingly clear that I was the only human being walking these paths today. Of course, every mirrored window of the expensive Virginia Quay development very likely hid another, possibly just as convinced of their solitary condition inside the insulated post-modernist block with the clouds pressing against the windows. As I navigated the river's edge via the silted remains of East India Dock basin a dog walker briefly appeared, crossing the park which was developed here to celebrate the turn of the last century. It remains as a monument to a previous era of hope and expectation - a "year of hope" totem inscribed with promises local children made to be harder working, better, more productive citizens sits beside an inert beacon - one of the chain which lit up the country at the appointed hour. Blackened and tired, it's corporate inscription lives on. I exit the park somewhat gladly - and delve between the high walls of former factories and yards which line the almost ridiculously misnamed Orchard Place. This twisting, narrow byway edges out to the very end of the peninsula separating the River Lea - or at least it's final incarnation as Bow Creek - from the Thames. Along the way, there is evidence of contest - a transport yard creaks and rumbles alongside artists' studios, a huge paper-clad fish dangles over 'The Causey' - a narrow, trash filled chasm which leads between buildings to river stairs. At the entrance to Trinity Buoy Wharf a decommissioned London cab sprouts a tree festooned with lights. They always said the artists would leave the Wick for Poplar - and it seems they're here before me. At the end of the road, the scene opens out into an expanse of dockside. The old lighthouse is one of the few permanent buildings here, beside a range of repurposed shipping containers turned into offices and studios. I pick my way between the parked cars and take pictures of the end of the Lea - the conclusion of a walk which I've never officially started. Across the river the metal works clatters and shudders. I find the cafe in a nearby container, it's outdoor area filled with objects reclaimed from the silt and mud. It's time to eat, grateful just to be among other people for a while.

Setting off again, I feel a little more adventurous. My feet are holding up well despite being so unpracticed, and the weather is at least consistent so far. I'd contemplated various options for the next leg of the trip - but the one which appealed most was to cross the Lea via it's last bridge. I'd checked variously via Google, and the Lower Lea Crossing was walkable. Indeed it had a broad, segregated cycle and footway beside its two carriageways of traffic. However, it seemed very few people actually did this. The ease of access by DLR and bus, and the strange lack of population in the immediate environs meant that this just wasn't a useful thoroughfare for pedestrians. As I retraced my steps and climbed up onto the pathway, I understood why. The road was quiet and empty, the hump of the bridge buckling in front of me. It was dry, dusty and windswept despite the damp stillness of the day. I climbed and surveyed the landscape - to the south, an elevated view of where I'd just walked. A forest of cranes, not from the long-deleted docks, but from the endless new identical blocks of flats being spawned along the river. Looking North, the oddly duodenal reverse curve of the Lea as it twisted onto itself, the empty isthmus of land earmarked as City Island rapidly growing into a small town in it's own right. Beside it, the dense green wedge of the Limmo Peninsula Nature Reserve supported the curving DLR tracks. Nearer to the bridge, the source of the dust - a Crossrail tunnelling site. As the road descended to the east bank, a scrubby embankment emerged. Just as I was beginning to feel once again that this was the least human place I'd walked for a long time, I spied a little well-worn pathway into the undergrowth. At the end of it was a makeshift den, hung with pictures and scattered with cushions. Someone lived here! Apparently undisturbed among the thunder of weekday traffic and the fumes of the nearby metal works. I mentally saluted them for surviving here, which felt like the very end of things, and climbed the stairs onto Silvertown Way.

As I descended from the viaduct near Canning Town station, I noted that civilisation was returning, albeit a very different one to that I'd left west of the Lea. Beside the road, the Canning Town Caravanserai project filled an entire vacant plot. Makeshift wooden theatres, play areas and restaurants crowded into the space - it was confusing and intriguing, and reflected the sort of community action which has quietly been happening around here for many years. This is an area where the mythical and the real East End collide - where waves of immigration wash on an overwhelmingly white, sometimes unwelcoming shore. Stereotypes linger in the heavy industrial air out here - at first I was amazed how many black cabs were ranked along the side streets, but then I realised that this is where the cabbies live. This is the honest, hard-working east which people tell you has long since disappeared. At the station I hopped on a bus to take me the short distance to Plaistow. It was walkable, for sure - but my feet were beginning to ache and I was aware that time was a far scarcer resource now these trips are much more infrequent. Weaving in an out of stops along the busy Barking Road, I alighted at Balaam Street and lurched into the suburbs again. A little way ahead, a rise in the road topped by a Pelican Crossing signalled the intersection with the Greenway - I turned west again, a little sadly. The temptation to pursue the path to it's distant end at Beckton was strong - but that's for another walk. This stretch of the path is less elevated and better used that the sections which I was more familiar with. Running between two sets of solid but ill-kept railings, the path crosses streets regularly at humps, a decorated metal arch welcoming the walker to the next long, straight section. Frequent cross-sewers join beneath the footway, denoted by a mass of gratings and a tell-tale whiff of decaying matter. At first the path was busy, but as I delved deeped into West Ham, the walkers fell away until I was again alone. Descending a slope onto Manor Road I realised that I'd been here before - the brief sense of familiarity disappearing as I turned north and set off once again along the long, walled chasm of the street as it wound around estates reclaimed from the ranks of victorian terraces.

Two tower blocks, Brassett Point and David Lee Point, lurched over the walls strangely and captured my interest. They stood out simply because despite the high density of life around here, there are very few tall blocks left. It's perhaps no surprise given the divisive nature of high-rise living in this part of London - the memory of Ronan Point is just a short walk away and ingrained in local legend. At the junction with New Plaistow Road I sensed a change again - the walk along Manor Road had been long and unusually warm in the February afternoon, but there was a chill wind whipping along this street of abandoned pubs and shuttered takeaways. The people are different too, and I'm aware that for the first time in a very long time in East London, there are only pinched, glowering white faces. This part of the world is culturally complex and highly contested - in the sense that there ever was a 'traditional' East End of cockney tradition, it was probably here - but anyone who scratches the uneasy surface knows that the real tradition here is of waves of immigration and - when things work - integration. Frighteningly, the thing which threatens this long-standing and uneasy equilibrium is opposition to immigration itself. The fear of difference, whipped up by odious cartoon right-wingers, is making integration harder and harder and creating the very difference which scares them. They're fuelling their own noxious fire, and here on the unassuming, practical face of things, I hear passing conversations about UKIP, 'pakis' and 'coloureds' similar to those which have probably taken place on these street corners for centuries, but rarely with such zeal. The only refuge is a church - and it's an ancient and peaceful one too. All Saints stands as a sort of traffic island, surrounded by the lowest-budget hotels and guest houses I can imagine. The churchyard is a puddle of mud, as an ill-conceived extension is being build in a quesy, 21st century ecclesiastical style. The long, gabled walkway to the main door is closed off and I'm forced to circumnavigate the building, taking in it's charmingly mossy older sections which are bolted unceremoniously onto Victorian alterations. During my circling I spot - and deviate to photograph - an abandoned pub - The Angel. Oddly complicated with a small tower and spire, and with the bold remains of a painted gable advertising port for 3/- a bottle, it's a shame to see it in decrepitude. Returning to All Saints via the eastern gateway, I hoped to gain entrance, but today the church was off-limits. I found a bench in Stratford Park and rested for a while, finally digging into the supplies I'd purchased in Poplar, which felt like a world away.

The final section of my walk took on the desperate rush which often descends on these jaunts in the afternoon. An awareness of time, of the limitations of my own tired body and of the sense that I'm still in unfamiliar surroundings which pushes me to head for safe ground. This time, it wasn't far away - and there was still time for a brief detour along the route to familiar surroundings. Edging into the centre of Stratford, I tried for coffee but gave up at the sight of the queues. In defiance of all the doomsayers, the Stratford Centre remains bustling despite Westfield towering beside it. The shabby, unpredictable shopping centre remains a magnet for the locals while the tube brings outsiders into the shinier, newer buildings just feet away. I explored a little, finding Joan Bakewell's Theatre Royal snuggled in between new buildings and curving access ramps. The bright, blood red frontage is a reminder of yet another different East End, nestled against the new. Unable to face the crowds of Westfield, I skirted the station and zigzagged along Angel Lane, over the railway and into the strange interface between Leyton and the Olympic Park. My aim here was to walk through the former Athlete's Village, now emerging as a new suburb. Access was via Penny Brookes Lane - a long, straight road which divides Westfield from the unimaginatively dubbed "East Village", coming to an end on Celebration Avenue. Aside from the contrived street names and the eastern bloc architecture, the place doesn't feel entirely artificial. It is incomplete and unresolved of course - the ground floor of each block gaudily advertises the space inside and how it could be used. Some of them show promise - "reserved for dry cleaner" or "let to wine merchant" - but most are as yet empty. Above though, many of the windows show signs of life - bicycles on balconies, washing hanging. Trains rumble close by, under the earth. Just like Leamouth and Canning Town though, there are few people around. I cut through a pleasant urban park - just beginning to lose it's 'planned' feeling - and cross into the Wetlands Walk part of the park. noting that even now a security guard is directing people walking along Olympic Avenue. The wetlands are interesting and peaceful, populated by water birds unconcerned with the manufactured nature of the habitat. The pathways through the park however are sealed off - not for security now, rather to see work done to rationalise the huge bridges into a more reasonable post-games walkway. I ascend to cross the River and head down to the towpath. This is possibly the last section of the Lower Lea I've not walked - the tantalising gap between where I left my last walk and the Eastway. Glimpsed longingly from the road many times, but always out of reach until now. I savoured the walk, taking in the sweep of the park and the Velodrome glowing in low sunshine beside the permanent Olympic Rings.

In a sense, this completed a ten-year long excursion through this part of the city. The sense of completion wasn't lost as I slogged the last few steps to the bus stop on Ruckholt Road, and made my way back to contemplate the walk over coffee in a familiar station haunt. My pattern of exploration here has followed a method - albeit unintentionally - over the years. The railway is the advance party - and I'll strike out through new territory first in the safety of a train - but then, slowly but surely I'll edge out on foot, covering the terrain in detail. Today's walk marked both a new eastern frontier, and the end of a long-standing exploration of what lay within it. As ever though, the very act of walking and choosing a path suggested future walks in the turnings I couldn't take. I can only hope it won't be long before I can take those paths too.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

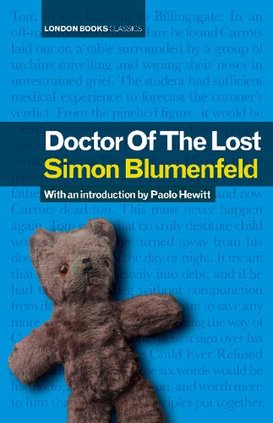

By the time Simon Blumenfeld's writing career had begun, the East End he writes of in this - his final novel under his own name - had all but disappeared. In fact, this potted life story of Thomas Barnardo documents some of the changes which Blumenfeld would have seen himself, being born a son of Sicillian Jewish immigrants in Whitechapel. Through the eyes of his Barnardo character, Blumenfeld surveys the East End at the end of the 19th century, taking in its squalor and injustice and balancing it with the now familiar tropes of character and spirit to portray what must have seemed an impenetrable horror to the deeply religious Dublin medical student on his arrival in Stepney. It would be easy to characterise this as an opportunity for Blumenfeld to advance his communist views, but there is a tension here - while Barnardo wishes to see "No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission" and is seemingly unconcerned with the underlying political and social injustice, he regularly debates this with Haddock - "The Black Doctor" who sees no hope without societal change.

Taking it's factual cues from historical and the public records of the remarkable Barnardo, the novel fills the gaps with surprisingly effective supposition and dramatisation. Barnardo himself is sometimes unsympathetically devout, but bristles with energy and indignation too. Filled out with engaging characters drawn from his real experiences in the East End, the sharply drawn dialogue and edgy cockney wit which Blumenfeld deployed in the earlier, more controversial "Jew Boy" return. The scenes in pub and music hall resound with a reality which stems from first hand experience - as Blumenfeld was for over thirty years a writer for The Stage, in fact attaining the official record as the "oldest living columnist" during his time there. Topographically, the novel is tightly secured into the triangle of Stepney, Mile End and Limehouse - areas Blumenfeld would know well, and from which he draws rich descriptions of places, some now changed immeasurably. When the novel does stray out of this liminal zone it is a little more fanciful and blurred, echoing the strangeness of wealthy London to those who lived their entire lives in the East, and equally the horror and disbelief the upper classes felt looking in from outside.

"Doctor of the Lost" tells a fair approximation of the sometimes forgotten life of the man behind the charitable juggernaut which now has a global reach. As a novel though, it works better - with many passages of wonderfully crafted descriptive work which provide Blumenfeld with the opportunity to explore his territory in the East End. It would be terribly easy to enter a debate about how much of it is truth - but the saddest truth is that the need for a Barnardo ever arose in Victorian London.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.