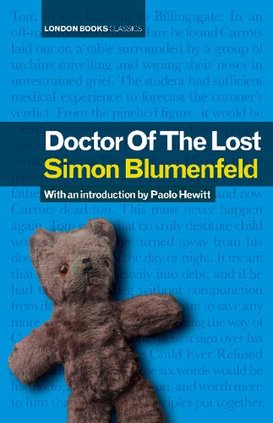

By the time Simon Blumenfeld's writing career had begun, the East End he writes of in this - his final novel under his own name - had all but disappeared. In fact, this potted life story of Thomas Barnardo documents some of the changes which Blumenfeld would have seen himself, being born a son of Sicillian Jewish immigrants in Whitechapel. Through the eyes of his Barnardo character, Blumenfeld surveys the East End at the end of the 19th century, taking in its squalor and injustice and balancing it with the now familiar tropes of character and spirit to portray what must have seemed an impenetrable horror to the deeply religious Dublin medical student on his arrival in Stepney. It would be easy to characterise this as an opportunity for Blumenfeld to advance his communist views, but there is a tension here - while Barnardo wishes to see "No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission" and is seemingly unconcerned with the underlying political and social injustice, he regularly debates this with Haddock - "The Black Doctor" who sees no hope without societal change.

Taking it's factual cues from historical and the public records of the remarkable Barnardo, the novel fills the gaps with surprisingly effective supposition and dramatisation. Barnardo himself is sometimes unsympathetically devout, but bristles with energy and indignation too. Filled out with engaging characters drawn from his real experiences in the East End, the sharply drawn dialogue and edgy cockney wit which Blumenfeld deployed in the earlier, more controversial "Jew Boy" return. The scenes in pub and music hall resound with a reality which stems from first hand experience - as Blumenfeld was for over thirty years a writer for The Stage, in fact attaining the official record as the "oldest living columnist" during his time there. Topographically, the novel is tightly secured into the triangle of Stepney, Mile End and Limehouse - areas Blumenfeld would know well, and from which he draws rich descriptions of places, some now changed immeasurably. When the novel does stray out of this liminal zone it is a little more fanciful and blurred, echoing the strangeness of wealthy London to those who lived their entire lives in the East, and equally the horror and disbelief the upper classes felt looking in from outside.

"Doctor of the Lost" tells a fair approximation of the sometimes forgotten life of the man behind the charitable juggernaut which now has a global reach. As a novel though, it works better - with many passages of wonderfully crafted descriptive work which provide Blumenfeld with the opportunity to explore his territory in the East End. It would be terribly easy to enter a debate about how much of it is truth - but the saddest truth is that the need for a Barnardo ever arose in Victorian London.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.