The Curse of the Curious: A Last Walk before Lockdown

Posted in London on Saturday 7th March 2020 at 10:03pm

Pre Amble

I began writing about this walk during mid-April 2020. The UK is heading into the fourth week of 'lockdown' - a precarious moment when a review of these conditions suggested it wasn't yet time to relax them. The mood hovers between unexpectedly good-natured compliance and the growing sense of a national tantrum about to burst. The economy is stuttering, but those least engaged with it struggle most. For them, the monotony of their normal is only broken by some of the things they've seen stolen by this unseen adversary: a precious moment of peace when everyone leaves the house, the belonging of school-gate gatherings, the conspiratorial break-room banter of work. For me, this period has been strange but relatively easily endured. Working for a local authority has exposed me to something of the growing horror, but also much of the remarkable response. I've been able to work largely from home, marshalling resources remotely and massaging decisions into shape like a nuclear scientist reaching into the mechanical arms which will manipulate dangerous isotopes. Any sense that this is easily achieved should be avoided - so many of us aren't ready for a virtual existence. The alluring ease of a virtual flounce with the click of the 'end call' button is always present. Who knows what is happening just off-camera? The outcomes are often tiny and trivial and feel remote from the reality of the situation. But, at the very least, I feel like I'm somehow useful in the margins.

When I walked this largely aimless excursion, the virus was a growing curiosity. A slow-burning 'other' thing, in another place. It had no form or substance yet, merely a rumour of contagion. Heading into London felt risky in the mildest sense. It seems impossible we knew so little, such a short time ago. But reflecting on that journey into a world which was largely functioning utterly normally, I can see how conspiracy theories have taken hold. Life, torn from its usual moorings, has left a tantalising but terrifying gap between us and the shore. The gap swirls with information - the very channels which keep us connected carrying a ghost signal of what-iffery and nudging, knowing crackpotism. Bill Gates as an unlikely antihero, misreadings deliberate or unintentional, a quantum world where it is both 'not the time for politics' but when suddenly people have an endless stomach for the discussion. Our post-Brexit trust for experts still an open wound, we're all become epidemiologists or economists now. When I was walking from north of the M25 into the city, I wasn't sure what I was attempting to achieve. I had only a vague notion of my plan, a long regulatory inspection at work had stolen every sliver of planning time. I was walking almost blind. But I realise now I was trying to close this slowly growing gap - trying to hold my worlds together against the coming storm, just as the wider world was breaking free of its tethers. By walking a north-to-south line into the belly of the slumbering city I was attempting to pin down something I'd otherwise lose hold of very soon. I've often taken walks on this axis when things have felt tenuous or bleak, and here I was again...

When and if I'll walk into London again is as unclear to me now as it was when I stumbled sore-footed onto my homeward train after this walk. London feels remote and impossible, but of course, it persists - sprawling and uneven, both self-aware and supremely egotistical. I've never wanted to scour its bleak underpasses and dank patches of unloved woodland more than I do now. I can taste the metallic air and feel the vague crackle of urban threat without trying - because I've walked into it often enough to feel I need this recharging flux.

Amble

Until today I had only the most theoretical idea of Potters Bar. It is a cypher for a particular type of commuter-land misery, somewhere widely understood as utterly ordinary and unremarkable. You can slide Potters Bar into a comedy riff to short-circuit the descriptive process. It stands as everywhere and nowhere. A shifting allegiance from Middlesex to Hertfordshire cemented a long, slow shift from provincial market town to city dormitory which had been on the cards since the arrival of the Great Northern Railway a century before. Outside the station buildings, topped by an uncomfortable post-modernist office block beside a bus circle, a tiny shrub-infested garden almost hid a memorial to the seven victims of the 2002 derailment. Regarding the modest, almost apologetic tribute, I recalled the day unusually clearly - a commuter myself back then it focused a wandering mind on the train home that night. The remembered sight of an upended carriage forcibly removed from the rails, sitting askance under the platform canopy was a cruelly accurate simile for the then decade-old corporate separation of track from train services. These events would finally put paid to that use of private contractors in track maintenance, after many months of disruption due to checks on similar infrastructure to that which caused the crash. The sheer normality of the bustle around the station - the busy Caffé Nero and the swirl of arriving and departing buses - felt strange. The pall of horror felt fresh and present and I struggled to shrug off this early gloom. Potters Bar is a town with two distinct centres - one, modern and chain-stored focused, coalesces around the station, and the other hugs the line of the old Great North Road a short way to the east. I set off across town to reach this second, slightly less salubrious focal point, noting that the street which climbed towards the ridge which the old topped was named, fittingly, The Walk. It was a warm and humid morning, the avenue alternating between tidy bungalows and sizeable semi-detached houses each with a clutch of reasonably new cars outside. There were few pedestrians on The Walk, and the ones who spotted me eyed with suspicion. There was no need to out on foot beyond the short skip to the vehicle, surely? Across the cricket pitch, the unlikely headquarters of Canada Life insurance dominated the pale sky - an incongruous if unambitious block which provided a convenient host for an infestation of aerials and antennas. Potters Bar had done nothing to shrug off its mildly unsettling suburban status just yet.

Arrival at the junction where The Walk met the High Street presented a choice for the traveller: to the north lay provincial England, starting semi-officially just beyond the bus garage which marked the end of the long journey from London for the familiar red buses. The road south would lead me into familiar territory: the bucolic outpost of Hadley Wood and thence to Barnet. It was a solemn reminder that I'd travelled more in these northern climes than perhaps I'd realised. There was a welcome if unexpected sense of geography slotting into place, tiles of land ordering themselves with a logic which at once made things more familiar and even more intriguing. My plan though was to turn aside from the old road and bear east across the last miles of Hertfordshire. As the convenience stores and pilates studios gave way to the last sprawling edges of town, I turned southeast onto Southgate Road. Most of the passing traffic did the same, as this was the gateway to the M25. The old A1000 pressed on south: a backwater for those who knew better than to brave the approaches to the Orbital route. Even on a sleepy Saturday morning on which people were beginning to shun the viral city, the traffic began to slow long before the interchange. The somewhat drab row of semis spread into a run of sizeable villas before the scruffy motorway fringe of fly-tipped woodland encroached on the immense roundabout, abnormally elongated as if it was awaiting some other convergence beneath.

Pedestrians were left to fend for themselves on the slip-road crossing. A pulse-elevating dash, and the knowledge that relative safety had been reached when the crunch of gravel underfoot meant you had reached the margin of the carriageway, where a spray of dust and stone kicked up by careering cars lay undisturbed. The bridge over the carriageway was a perverse sanctuary: howls of engine and groans of diesel churning beneath, but up here at least, I felt secure on a wide pavement. These places were easy to understand - you kept to your permitted zones and assumed the drivers who flashed past giving only the most cursory attention to those on foot would keep up their end of an unspoken bargain. The westbound on-ramp presented a further challenge - the long straight of the roundabout giving drivers ample time to accelerate into the turn. I scurried across and sheltered under a temporary variable message sign which flickered speed limits and traffic conditions back at the joining traffic. Stagg Hill disappeared quietly between the trees, flanked by a dusty white track leading to a clump of small industrial buildings nearby. There was a footpath - sometimes narrowed by overgrowth and often rutted and treacherous to walk. I was glad of it though - the few cars ascending the hill towards the Motorway howled by at speed, seemingly desperate to escape the environs of London while I was just arriving. The slow descent provided sweeping views over the last yards of Hertfordshire, a twin procession of high voltage lines marking the border. As ever, the change was imperceptible - a small sign welcomed me to Enfield, while behind me a larger board indicated I was leaving the 'county of opportunity'. The slope bottomed out beside another cluster of light industrial buildings around a farmyard. The track which had shadowed the road downhill curved to the west to meet this silent and rather sinister facility. It was probably just a farm, but in the quiet warmth of a morning where the very air seemed hostile, the mind conjured unabated. No-one and nothing moved within. A stand of modern metal railings beside the road marked the passage beneath of the Salmon's Brook on its journey towards the River Lea. A sluggish and reluctant stream here, tangled in weeds and roots, and glistening with sickly smelling chemical run-off, I recalled its lower reaches, penned in by concrete and even more polluted. I was closer to its source than I'd dared to walk before - my horizons having slowly expanded out of the suburbs and into the rural edges of the city over the intervening years. The road rose gently ahead, a narrow band of development appearing on the edge of the clay ridge which separated the Salmon's Brook from the Monken Mead Brook. Once again I was approaching the intersection of several previous walks: to the west, the impressive houses of Hadley Wood shimmered in the morning sunshine, while ahead of me the carefree cafés and futuristic architecture of Cockfosters signalled the beginning of London's unabated conurbation. I'd soon pass a point where the shift would be palpable, a puncture in the skin of the city - the medical metaphor not lost on me today. To the east, the countryside continued: a patchwork of fields fading into Trent Park. The stream of traffic leaving London continued, and I pushed on against it.

Development hugged the western edge of the road, showing a defiant cliff of high-value apartment blocks to the wildlands beyond. Some of the older properties had made the inevitable shift to high-end convalescent or nursing accommodation, others had succumbed to modern rebuilding in unsettling 1990s parodies of the vernacular. Narrow, curving ramps which wouldn't meet current regulations swooped into underground car parks, while automatic gates silently shifted into place behind incoming vehicles. Once, beginning a walk from Cockfosters, I'd wondered from where the expensive cars and clothes evident in the carefree and cash-rich pavement culture emerged? I'd found the source: a band of out-of-town bolthole apartments which while handy for the Piccadilly Line would almost certainly be linked to the City by a car journey. From one underground car park to another - no risk of breathing the tainted air which now more than ever had a bitter tang of danger about it. A little way along the ridge the uninterrupted views of countryside which Estate Agents would no doubt be carefully noting were compromised by the uncanny helical concrete stem of Cockfosters Water Tower. Built in 1968 for the Lee Valley Water Company, the elegant hyperboloid latticework twisted into a bulky drum festooned with telecom aerials and conductive spikes. The architect was Edmund Percey - veteran of a number of fascinating similar constructions. On leaving the RAF, Percey began work at the London County Council before moving to Scherrer & Hicks where he was involved in numerous industrial architectural schemes. His work includes the Lee Valley Water Company headquarters in Hatfield which incorporated a full-height relief by William Mitchell, another former LCC employee. The amalgamation of water supplies in London into the almost amusingly shifty and anonymous Affinity Water is a history of declining municipalism. First, the Colne, Rickmansworth and Lee Valley companies collapsed into Three Valleys Water, then the service-industry giant Veolia stepped in. Eventually, water became big business and the company letterhead became a litany of investment banks and finance houses. Affinity makes more sense in this context: a press release compatible, gently positive name for an unseen industry. Nothing to see here: nearly 1200 cubic metres of water stored for our convenience. Move along, and let the heavily fortified gates to the facility persuade you that this architectural marvel isn't worthy of photography. It's a utility, after all. I lingered a little longer than perhaps I should at the gates and maybe it was the frisson of paranoia in the air, but I'm sure more cameras were pointing at me when I left that when I'd arrived.

Resisting a diversion into the bucolic corner of Cockfosters which remains along Chalk Lane, I re-entered modernity via an impressive gateway with Charles Holden's bus shelters flanking the street and providing access to the cathedral-like cavern of the station which marked the end of the line. The line curved towards the road below ground level, the concrete beams rising above the line but hidden from the street above. To the west, the sleek 1960s lines of Metro Point framed the concrete bus shelter perfectly. This futuristic, white slab of offices is regarded by Enfield Council as of 'moderate architectural quality' but it typifies the low-rise schemes which cluster around the Underground's termini. Beside the station another example, Holbrook House, was nominally in NHS ownership but looked abandoned. Its glassy exterior coated with reflective material which peeled sadly. I slipped into the station in the hope of using the facilities but found them locked out-of-use. I'd been somewhat apprehensive about how things might feel on re-entering civilisation when it was busier a little later in the day, but it seemed all was well. The light and airy concourse was busy with travellers, and there was little hint of menace in the air. I returned to the street and walked the broad shopping parade as far as the roundabout where the A110 crossed my route on its journey towards World's End. This was a familiar spot where I could find topographical moorings: the moss-covered 'County of Middlesex' sign and Pymmes Brook tumbling in its concrete trough through Oak Hill Park. My navigation of these northern heights would never be complete, but it was becoming comprehensive - and in a pinch, I'd found myself back here again.

I headed south along Chase Side, named for the great hunting grounds of Enfield Chase and once famous for sporting a run of fine coaching inns along its length. This ancient way provided a route from London into the southern flank of the Chase, which was until the 18th century part of a great forest stretching north over much of the ground I'd covered today. Legally unrecognised after 1777, the once expansive woodland was divided and sold, with much being deforested very swiftly. This paved the way for the suburban expansion which engulfed the forest hamlets of Osidge and Winchmore Hill, creating the low-rise dormitory landscape which has survived largely unmolested into the twenty-first century. There were notable patches of the old geography scattered along the old road: to the west, the forest remnant of Oak Hill Woods stretched towards the high ground of East Barnet, while to the east Bramley Recreation Ground housed the tumbledown changing facilities of Saracens Amateur Rugby Club. The top-flight team turned professional in 1995, heading for their new home at Allianz Park via several ground-sharing agreements. This suburban scrap of grass would never do for the kind of plans the new owners had. So, their home for almost sixty years was now a haven for dog walking and pram pushing when not in the service of the part-time team, the tall nets along the road torn and flapping in the breeze. Meanwhile, Chase Side continued its curve towards the southeast, following the almost imperceptible valley of the northern branch of the Houndsden Gutter. The road hugged the slight interfluvial ridge, now dividing a sea of pleasant suburban villas. Beyond the gardens, the hidden river carved an ever deeper path around the edge of Southgate, causing the Piccadilly Line to climb over its valley on a viaduct before plunging into the hillside and into Southgate station, which despite sitting at the edge of this valley is the most northerly station on the network to be truly underground. The steeply sloping ground behind St. Andrew's Church had once been a recreation ground, sloping down to allotments on the valley bottom, but now a supermarket protruded oddly on an artificial plateau, with ramps descending to underground parking. Despite the presence of a huge superstore selling almost everything one could need, Southgate Circus still genuinely bustled in a way which many of London's minor centres don't often achieve. Cars swirled around the unusual figure-of-eight shaped traffic island, while the abandoned spaceship of Charles Holden's station shimmered through the heat and pollution. The brick curve of Station Parade wrapped around the beached saucer, flanked by columns with large Underground roundels which stood like sentinels at each end of a rank of bus stops. The station dates from the northward expansion of the Piccadilly Line in 1933 - something of a landmark year for Southgate with its elevation to Municipal Borough status. The ring of busy shops and cafés around the Circus still managed to convey something of that civic pride: Southgate was determinedly not just another parade of shops in a sleepy suburb.

I was tempted to linger around Southgate Circus, not least because its no-nonsense getting-on-with-the-job feel was at odds with the increasing viral paranoia in news stories pinging regularly on my 'phone. Paradoxically, this bluff busyness probably meant it was the worst place to be, so I continued south-west along The Bourne, immediately plunging back into a quiet residential area. Much of the eastern flank of the road was taken up by the beginnings of Grovelands Park, near an entrance to a Priory Group mental health and addiction facility, sited beyond the impressive Ionic columned villa of Grovelands House. The house was built by John Nash around 1798 for Walker Grey, a brewer. Grey secured the services of Humphrey Repton to landscape the extensive grounds, reputedly so that he need not have a view of other's chimneys. The house passed into the hands of another London brewing dynasty, the Taylors, who sport a lineage from a site in Stepney to the modern multinational Carlsberg Brewery. Ultimately, given the vast sweep of suburbia that now enveloped the park as the Taylor family sold off parcels of the estate, even the mighty Repton couldn't prevent the march of progress. In an unexpected twist, Grovelands echoed the fate of Repton's commission at Claybury, where his landscape gardens became the grounds of a hospital. However, they survive though much reduced and the park includes a sizeable lake fed by a second headwater of the Houndesden Gutter. From the shallow but marked valley into which The Bourne passed, along with the very name of the road and the long-deleted hamlet of Bourneside, it's likely this stream was once a more prominent feature of the topography here. Alas, it had disappeared from most maps by the end of the 19th century, while the stream exiting the park on route to Winchmore Hill remains, itself slowly disappearing behind back gardens. Roughly at the valley bottom, the impressive Inverforth Gates gave access into the formal avenue of the park, a gift from Andrew Weir, the 1st Baron Inverforth of Southgate who had little connection with the area save for his peerage. From the gates, my route became a long, slow clamber out of the valley and it was easy to see why The Woodman had remained a popular watering hole on the route since 1810.

Near the Woodman, the road divided: my route continued along what was formerly known as Dog and Duck Lane while Fox Lane turned south to pass through the long-since erased hamlet of Clappers Green. At the junction, a tidy triangle of land was trimmed neatly and provided with benches to form an unlikely oasis of green space. At the wider, southern extremity of the wedge of greenery, the grass grew tall and yellow within a fenced area. I crossed the road to find a small 'Borough of Southgate' plaque which explained that the pound was a 'relic of early days' and had been last used for impounding stray cattle in 1904. Retrieval came of course, with a fine for the owner of the errant livestock. It felt odd to imagine this spot being in open countryside, the pound and the inn standing among the trees. What was perhaps stranger was that it had been preserved for so long. The Borough of Southgate disappeared into Enfield by way of the Local Government Act 1963 which also put paid to Middlesex, but its considerable and grand public works endured hereabouts. Those works even extended to the protection this tiny patch of greenery, unmown and littered with cheap vodka bottles, in the midst of sprawling twentieth-century suburbia. Leaving the pound, I crested Bourne Hill and began the gentle descent towards the New River, snaking along the 100ft contour towards the City. This relatively easy route from the north was shared by both the railway heading into Liverpool Street and the ancient track of Green Lanes. I crossed the tracks on a curious footbridge which ran parallel to an abandoned road bridge. A more modern, wider crossing now curved to the south avoiding what appeared to be a significant bottleneck in the broad carriageway. The newsagent and laundrette were quiet in the afternoon heat, the road empty. The area felt suddenly deserted by humanity. A train clattered below, breaking the uncanny absence of activity. I hurried on towards the crossing with Green Lanes where a parade of buses shunted for priority at the lights while the verdigris-topped towers of St John the Evangelist bore witness over my road onward. I had only the vaguest memory of passing this crossing before when it would have course have been an insignificant waypoint on my route. Now though, having crossed the path again it took on the usual significance. Territory crossed and recrossed in this way feels like a kind of time travel - my footprints intersecting themselves years later in these suburbs which stop moving for no-one. The crossing of the New River was equally unmemorable, occurring on a fractured stretch of the New River Path where straying onto the street was frequently necessary. I didn't recognise the low parapet of the bridge on Hedge Lane in particular, but I paused to admire the curve of the still waters away north toward Enfield and their source. There was a strong temptation to stray south along the path, but that was a different journey.

Instead I headed on through the relentless ranks of side-streets populated by solid, familiar London homes. My feet were tiring from the long stretch of pavement walking and I was beginning to fall into an absent-minded fugue which sometimes descends on these suburban walks. It was time to rest, and unexpectedly I found myself beside the gates to Tatem Park. The park existed thanks to a remarkable feat of cooperation between the Borough of Southgate and Edmonton Urban District Council who jointly sought the donation of land by the Harman sisters, nieces and only surviving relatives of James George Tatem - the last owner of Weir Hall and heir to the Huxley family estate. Weir Hall stood at the west end of Silver Street, the most recent house being built on the site of a much older property by 1611. The building was demolished in 1818 and the site was turned over to market gardens. In the meantime, the area which would become the park I was now resting in, became the site of gravel pits and brick kilns feeding the expanding suburbs which grew as the sisters slowly disposed of the estate. Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, Tatem family correspondence refers to 'Gravel Pit Fields' and indicates the tenacious efforts of the councillors of both Edmonton and Southgate to engage with the agents of the Harman sisters regarding the site. Excavations in the gravel pits revealed a final surprise before the land was turned over to the people of the boroughs: ice age deposits rich in the bones of Mammoth and Mastodon were uncovered, the remains being turned up in such abundance that workers would often take home relics as ornaments or paperweights. The inhabitants of these northern suburbs were far from the first to dwell on the slopes rising from the Thames, and in 2012 they began a campaign to return these old bones to their home territory, completing the circle in this apparently insignificant corner of Edmonton. I rested a little longer than I'd planned before creakily moving on through the aspirationally named Hollywood Gardens - in fact laid out and dedicated in 1945 to Cllr George Hollywood. The rest of the walk was only a hazily uncertain plan, and this quiet spot seemed like a secure place to ponder my next move without too much urgency. But move I eventually had to, and it was to more familiar territory as Hedge Lane sputtered to a halt at Great Cambridge Junction, colliding with both the A10 and the mighty North Circular Road. I'd approached this location before and knew the drill: descend into the subway which passed between the layers of road, pick an exit and head out of the dusty, grim bowl as fast as possible. It was difficult not to linger though, and I had a hard-to-resist urge to watch the traffic flash past beneath me as I hovered over the road. Shaking myself free of the spell of the mighty North Circular, I headed south and surfaced at the corner of the A10. Hermitage Lane sneaked away to the east, following the course of Pymmes Brook where it re-emerged from a short culvert. The correspondence with the Harman sisters had been addressed from 'The Hermitage' - another lost house with links to the Huxley and Tatem family. The brook was not visible from this corner where I recommenced my walk south alongside the six lanes of seething traffic. The air was dry, clouds of road filth kicked up by buses swirled around me as I stumbled along the lines of ill-kept paving slabs. Pedestrianism wasn't encouraged here - except for the brief scurry to the bus stop. Small groups waiting for city-bound buses eyed me with suspicion as I flapped by, sweaty and tired. Who in their right mind would walk along this road?

I realised I was heading into further familiar zones as I passed under a none-too-safe looking metal footbridge which allowed pedestrians to cross the impossibly busy road in order to access the short run of currently shuttered shops and takeaways which lined the eastern footpath. A little further on I'd cross more than one of my previous walks at Lordship Lane, and I had to decide where to head now. Traffic slowed and lurched, horns sounding in a futile attempt to gain ground at the lights as the fractious front rank of vehicles snarled at those of us who dared to cross on foot. Ahead of me, slicing through the broad ellipse of land created by The Roundway was the Tower Gardens Estate. Designed along the principles of the Garden Suburb, this impressive swathe of good quality public housing began construction in 1899 but was slowly expanded throughout the early years of the century as the remainder of Tottenham's farmland finally disappeared under paving. The district was growing, in large part due to the slow exiling of poorer residents of the inner boroughs to the new suburbs. Architecturally the houses were pleasant, well-spaced and provided with both front and back gardens, the latter accessed through arches penetrating the short terraced blocks. The site was developed chiefly by two London County Council architects: the northern segment by George Topham Forrest who had cut his teeth on similar projects in Leeds, and the southern by W.E.Riley, a military veteran who spent much of his career battling the interests of private architects in their attempt to intrude upon and denigrate the work of public sector departments. By 1939 over 2200 dwellings for the 'well-to-do working classes' had been built, including a small contingent of flats dedicated to housing those displaced by slum clearance in Shoreditch. The resulting estate remains coherent and comforting largely due to a very early designation as a Conservation Area which thwarted most of the 'right to buy' improvements which might have been perpetrated by the residents. In many ways, the area has changed very little since the architects began their work: the low hedges and red-brick cottages with distinct nods to the Arts and Crafts style cluster around a central spine known as Waltheof Avenue, named for the Earth of Northumberland who in 1065 or thereabouts took ownership of the manor of Tottenham. Waltheof's own north-south divide was not as harmonious as the two architects responsible for Tower Gardens, as he left a trail of intrigue and bad blood in the north of England before becoming entangled in an ill-advised rebellion of Earls against William I who finally had him executed. Waltheof lived on as an avenue through the development: a common green space which once included tennis courts and a community centre, providing a central boulevard for the suburb and continuing the line of the A10 southwards while traffic was forced to spiral off east or west, depending on its destination.

For a little while at least, I reversed that walk which seemed so improbably long ago now. Crossing into Downhills Park I followed its rather sedate central avenue - known historically and for reasons unknown as Midnight Alley. The quiet path divided the two distinct halves of the park - to the west a broad, flat recreation ground used by local Rugby teams, to the east a formal rose garden and café. Once the largest private park in Tottenham, Downhills was named for a large house built in the northeastern corner of the site in 1728, and rebuilt and extended at various points over the following sixty years. Also occasionally, and confusingly known as Mount Pleasant - as were several other local homes on the high ground here - the house changed hands frequently during the 19th century as the fortunes and standing of the area changed and suburbia swept around the park. By 1902, Tottenham Urban District Council had acquired the site for the local people, demolishing the now decrepit house while retaining the formal gardens and turning the area over to tennis courts and other amenities. The western edge of the site was described by the Palace Gates branch which swept southwest towards West Green station near the southern tip of the park. The line's path had been obliterated by the modern buildings of Park View Academy, but across the street, beyond the bus-stop, the tell-tale brick parapet of a bridge over nothing stood guard. Should the original Crossrail project ever complete its work and move onto Phase 2, this line would be shadowed by an underground branch from Seven Sisters, repairing the damage wrought to the network in 1964. For now though, the railway is a memory recorded only in the diagonal slash in the street pattern here. Whenever I pass this point there is considerable traffic from the nearby Seventh-Day Adventist church, but today things felt a little subdued. The bus stop was not thronged by worshippers and the area around the small but sturdy War Memorial was quiet. I wondered about the news from the world outside, and whether the congregation was already being extra cautious - or perhaps my timing was just off? I continued south along Cornwall Lane, once again crossing the trackbed of the erased railway, near which a small electricity substation building gave a striking insight into the growth of these suburbs. The Northern Metropolitan Electric Power Supply Company was a private undertaking based in nearby Wood Green, until it was absorbed into the Eastern Electricity Board on nationalisation in 1948. Aside from the fine office buildings which are now a self-styled 'arts hotel', little evidence remains of this local enterprise aside from the tiny brick building beside the bridge parapet, inscribed N.M.E.P.S Co. in fine, art deco style lettering. The road felt long and featureless, and there was an unexpected sense of unease and urgency growing in this walk. A sense that I had to reach a destination but little clear idea of where I was heading. The early part of the walk had seemed logical and linear - a permeation of the city from the northern fringe - a theme which I'd been worrying away at for months. But now, as I passed into Inner London I'd begun to wonder what I was really doing here? These last few weeks of turmoil and pressure at work meant I'd done nothing to think through my route beyond the earliest stretches. Now, I was suddenly considering the uncertainty ahead - the possibility that I might not be back here for a while. I'd been in this bind before of course - but always managed to navigate around it. This was different. Distracted, I tumbled out unexpectedly into St. Ann's Lane opposite the sprawling hospital campus. A sizeable length of the site behind the institutional brick wall was under redevelopment, but beyond the hoardings the site retained the character of the North Eastern Fever Hospital, built in 1892 by the Metropolitan Asylums Board. The hospital was one of a ring of facilities to treat and isolate infectious disease around the city, but had originally been shelved in 1890 as an unnecessary expense. An outbreak of Scarlet Fever soon followed, convincing the authorities that the site should be developed after all, and despite much local opposition to such a hospital in the now busy suburbs, a temporary facility with 500 beds was soon in operation. The hospital provided wartime support for the American Expeditionary Force before joining the NHS as a general hospital, with a range of services located in the generous accommodation. The site has though, never been popular, with its widely spaced blocks proving difficult for patients to navigate. The very space and isolation which was built to protect its original patients now inconveniencing their modern counterparts.

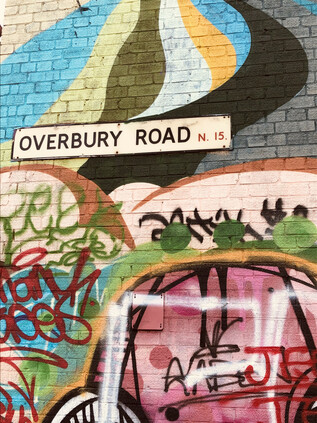

I zig-zagged south again, along Hermitage Road and under the railway line from Gospel Oak at one of the few crossing points into the Haringey Warehouse District. I'd passed through before, on more than one occasion when walking along the New River which forms a southern border to the zone atop a steep, grassy embankment. This sequestered corner of the borough was once home to a huge variety of industry: piano manufacture, cabinet making and confectionery among others - but by the 1980s was largely a zone of derelict premises and small-time semi-official businesses soldiering on through recession in the workshops and lock-ups which remained. It's a story echoed across the eastern districts of London: of aspirational populations moving on, industry declining and a slow, stumbling journey to urban renewal. The progress here has been slower than further east, the creatives picking up the baton rather less eagerly - but as I turned into Overbury Road with its long lines of light industrial units in the shadow of the huge brick chimney which marked the site of the former Maynard's sweet factory, I was met with a surprisingly colourful site. These long-since abandoned units have gradually been repurposed as artist's live-work spaces and while often not visibly improved from their former condition, were a riot of colour and variant purpose. A rank of wheeled bins paraded along the pavement, occasionally interrupted by bicycles or stacks of wooden palettes, half-finished projects caught in a snapshot of an area changing quickly. At the junction with Netherton Road, old collided resolutely with new: the brightly coloured converted warehouses meeting a row of more traditional businesses, mostly engaged in the final stages of the lifecycle of the automobile. At the end of the street the curious squat building at the head of the Victoria Line ventilation shaft glowered, while above the collapsing garages and dubious MOT testing stations, the tall Victorian shop buildings of Seven Sisters Road reared up, their lower floors below the level of the street. I trusted the map and shuffled into the stinking and unwelcoming corner where the former Courtney Pope factory had become an affordable housing collective, and began the ascent of a steep, damp stairway to street level. The crevasse between buildings was as brightly adorned as the buildings below, and emerging into the shabby gloom of the main road above was a shock. I'd worried about finding those life-affirmingly strange, transporting moments on this ill-considered walk - but this transition had surely been one of them.

I was footsore now, and I still had no real plan - but I decided that I should at least pay my respects to the New River properly. Eschewing the long curve to the east, I cut through the remaining unrefurbished blocks of Woodberry Down to reach the path. Once near the river it teemed with walkers and still reflected the changing strata of the local population. Expensive buggies cut deep grooves in the unmade surface with aspirational parents at the helm, while young couples shuffled along deliberately slowly, prolonging their rare moments of privacy while on the path. I swerved between them, eager to get refreshment from the supermarket before heading south again. I could have continued a little further to regain the familiarity of Green Lanes but instead, I decided to take a new route by following Lordship Road between the expanses of the East and West Reservoirs. Once out of the orbit of the shining glass towers in Woodberry Down, the road quietened and pedestrians evaporated. It was just me and the occasional local heading for the shops. The afternoon had become still warmer, the sky a churn of clouds and the air oppressive. I pushed on despite feeling tired and a little dejected by the slow decay of this little island of community on the fringes of Hackney. My route felt endless and still aimless as I trudged on, the road finally dividing around a narrow building which had once been the Parish Watch House and Fire Engine Room. The lock-up moved onto this site in the yard of the Red Lion in 1824 having previously been sited on the south side of the long-since disappeared Hackney Brook. This establishment passed into the hands of the Metropolitan Police in 1831, but despite maintaining it for a further forty years it was little used for incarcerating prisoners after 1834. Lordship Lane skirted the site and the neighbouring Inn, ending abruptly on Stoke Newington Church Street. This picturesque little lane, fronted by largely unspoiled brick shopfronts would have been unremarkable had it not seen an improbable change in fortunes in recent years. It would be easy to be judgemental and unkind about the transformation into a hipster destination: to take cheap shots at the coiffured facial hair and carefully assembled vintage outfits. It is, after all, what self-styled bloggers or writers are almost duty-bound to do when in the area. But in fact, the place felt rather energised by this presence. Removed from the centre of the city, there was a little less of the desperate ache about the place. The narrow street was lined with pastel-painted, independent businesses which harked-back to the glory days of the London High Street. Just to show that this gentrification was mature enough to have gone mainstream, the occasional national chain sneaked in a branch here and there, taking just enough care that it didn't clash with the parade of wood-fired pizza parlours and bespoke childrenswear boutiques. A sizeable branch of Nando's did its level best to remain anonymous from the casual pedestrian in a way that no provincial shopping centre counterpart ever would. In a courtyard nearby, a teenage idol of mine sold records at his pop-up emporium, Ecstatic Peace Library. It all seemed utterly unlikely but oddly felt like it made a sort of sense. The street vibrated with life: groups of young people promenaded, while weekend fathers wheeled children between them on the precarious strips of pavement. The bars had their shutters open, and chatter and vape fumes filled the air on the street. It felt carefully curated - people being seen just how they wished, in the company and situation which they hoped would convey the right message. Again I thought how oblivious they appeared to the unseen menace which seemed to be creeping closer, and looking them in their passing, innocently unconcerned faces I wondered if perhaps I was the one being alarmist and risk-averse? I turned aside rather thankfully from the crowd into the long sinuous curve of Albion Road. The shops here were crumbling and shuttered, they sold what people needed and folded quietly when their requirements changed. There were no mission statements or manifestos here, no popping-up or curating: just the collision of Victorian avenues with low-rise post-war flats - familiar, but after the subtle and carefully-kept curve of Church Street, notably jarring. This felt a little easier to navigate.

Shuffling onward, I unexpectedly found myself at Newington Green - the meeting point of roads from all directions, converging at a swirling gyratory created by a small island of public garden. I navigated around two sides of this quadrangle of arms, passing fancy and expensive restaurants and impressive townhouses-turned-offices with discreet brass plaques. There were dwellings too: in rather cramped but expensive-looking units wedged into scraps of land between more venerable buildings. I was familiar with this place via my equally abrupt decanting from the endless tramp along Green Lanes, and knew too well the risk of mistiming my exit and ending up deeper than anticipated into the suburban pattern of streets. With care I was able to head south again, onto Southgate Road - thus connecting the beginning of my walk with its nearing end. Tiredness was overwhelming me now, and the last trudge through the quiet streets of De Beauvoir Town felt like a fitting calm-before-the-storm entrance to the City of London. My travels have taken me often along the streets east and west of here, but this was new territory for me. I felt no shame for my omission: De Beauvoir Town has often been overlooked and unregarded. The land was acquired by William Rhodes in 1821 as the site for a speculative, high-class development of fine town houses, their location improved greatly by the opening of the Regent's Canal in the previous year. Work began slowly, and the development was soon mired in legal proceedings with Rhodes eventually found to have obtained the lease to the land unfairly. The rights reverted to the De Beauvoir family, but the moment had passed. While Rhodes and the De Beauvoirs had scuffled in court, the grand squares of the West End had taken shape and the pattern of wealth and privilege in London which persists to this day had largely been settled. De Beauvoir Town, incomplete and truncated in scale, soldiered on into the 20th century. Quiet and unloved despite its fine houses and distinctive square. Its lack of popularity and perhaps those historical pretensions to grandeur made it an easy target for the upstart borough planners of Hackney who turned great swathes of the original area into experimental new estates clustering along the banks of the Canal and replacing the narrow belt of industry around Kingsland Basin as it too lost a foothold. Perhaps it was this underdog character, along with the relative seclusion. which attracted the attendees of the 5th Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party to the Brotherhood Church on Southgate Road. This stormy clash of revolutionary and democratic rhetoric was decided from the outset with a Bolshevik majority in attendance - paving the way for a revolution in Russia and the creation of the Soviet Communist Party. Lenin, Stalin, Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky attended the congress - though none of these future luminaries were elected to the Central Committee during the proceedings. Their stars would rise later, the impact rippling out through history from this sleepy corner of Hackney.

The history of concealment and secrecy here persisted into the later years of the century too. In 1969, William Lyttle inherited the large 20-room home which stands at the angle of Stamford Road and Mortimer Road, a broad triangle of land created by the diagonal street pattern which survived from the early, much grander plans for De Beauvoir Town. The retired engineer set about constructing a subterranean wine cellar - but having "got the taste for it" began to tunnel out from under the property with remarkable industry. It is hard not to be captivated by the idea of Lyttle - the 'Mole Man of Hackney' - silver-haired and bearded, hacking his way through the earth of London to create this network of secrets and stashing the spoil along with countless other artefacts and curiosities within the walls of his huge home. But the impact on his neighbours over his four decades of tunnelling was considerable, and eventually bought about his downfall. Intermittent power supply issues and unstable foundations plagued the area and eventually, in 2001, the appearance of a sinkhole which hinted at the vast scale of his excavation was the last straw. Hackney Council finally acted, eviction proceedings finally finding their way to the High Court by 2008 where Lyttle was banned from the property and order to pay £293,000 in costs. Lyttle briefly returned to the property in 2009 to find his constructions partially filled with aerated concrete, but was soon ousted once again and rehoused on the top floor of a tower block on the nearby De Beauvoir estate to prevent him from tunnelling again. He died in 2010, his purpose and vigour lost, but not before he had knocked a hole between the rooms of his new home. The Mortimer Road house is now the home of artists Tim Noble and Sue Webster and a Vogue show-piece, rebuilt by Adjaye Associates with multiple entrances and exits to echo its unlikely history. The details of Lyttle's clandestine works, along with an exploration of his intent can be found in far greater detail in Iain Sinclair's affectionate address to his then increasingly threadbare and complex home turf 'Hackney, that Rose Red Empire'. But as I neared the end of my own day of sometimes rather directionless walking, I was struck by a remembered phrase from interviews with Lyttle at the time of his eviction:

Curiosity is my curse. If I make a start, I must know where it ends

For me, it would end at the gates of the City. I'd crossed the Canal at Rosemary Branch Bridge - named for an ancient part of the Parish of Finsbury, long since absorbed by the growing industrialised fringes of the city, and headed rather haphazardly across Hoxton via Shoreditch Park and Pitfield Street. I finally crossed the threshold via Curtain Road, piercing the boundary in the well-trodden territory around Great Eastern Street. I was surrounded immediately by memories of prior visits, quiet nights surveying the Overground from above, and walks beginning or ending here. This part of London holds a special, sometimes bittersweet, place in my mental map of the city - and signifies that rarest of things: a part of the territory I genuinely share with someone. Perhaps that's why, as I made a tired and desperate trudge to Liverpool Street station and much needed coffee, I felt melancholic and afraid. I felt, just for a moment, that the virus was stalking my steps and heading into this sacred - to me at least - spot. It seemed like my ever-tenuous sense of my own place here was under siege. As the wall of buildings announcing Broadgate Circus towered over me like walking into a tsunami of glass, I couldn't know what would happen, or how things would change to accommodate something we may have to live with for years to come. But thinking back to the very origins of this ill-planned and much-needed escape in Southgate led me to the words of Leigh Hunt, a poet of those emerging suburbs:

It is no remote infection - no 'Plague of Athens'. The disease is next door, - a pestilence that loungeth at noon - a dandy cholera.Leigh Hunt - Table-Talk, 1851

As I climbed aboard the homeward-bound train at Paddington that evening, I took a photograph of the sleek new carriages under the impressive curve of the station roof. I wondered when I'd be back, and in what strange circumstances I'd be travelling? The world felt uncomfortably imprecise and uncertain, the solidity of Brunel's engineering at odds with the forces which moved around it. I felt fear more keenly than I had for years - the impending sense of loss that only comes from allowing oneself to connect. Strange times were ahead, for certain.

You can find more pictures from the walk here.

Now and then, the internet still amazes me. It's easy to sometimes dismiss any remaining capacity for surprise in this cavernous echo chamber which I've been roaming since 1996, but oddly and when least expected it can come up trumps. On Twitter today I was amazed to see someone sharing an interview I did with Daniel Johnson back in 1992. I prepared to cringe at the irritating exuberance of my youth, but it actually remained fairly interesting and aside from a perhaps not-unexpected fascination with Daniel's very personal style of composition, the answers gave a little insight into someone who was back then something of a mystery to most of us.

After a little discussion, the rest of the fanzine showed up: a six-page effort from Theme Park in Brighton, which alongside my work, included an interview with Brown Tower and reviews of a bunch of records which I'd owned and loved too. A real blast from the past. Topping it all was an ad for Traumatone which spoke of a time when I felt like I was achieving something small but significant. A time when the postman's arrival was awaited with genuine interest, and when a transatlantic communication took four working days or an inordinately expensive 'phone call. It was just what I needed to see in the midst of a gloomy and challenging month when the dark days of winter stretched ahead and there weren't any plans on the horizon. It reminded me that now, just like back then in 1992, I might be ploughing furrows which seemed to be of little interest to most people, but I did it because it made me happy and proud - feelings I don't allow myself access to nearly often enough.

So as I sail into the busy, challenging and uncertain beginnings of a new decade I'm going to share this little nugget from the past. It's a reminder that small things can feel satisfying and significant, and that the impact of what we do is often more important than its magnitude. It's also something to remind me to get off my backside and create things this coming year. If I could do it then, dogged by the social anxiety and inexperience of youth, then perhaps I have far less excuse now!

You can see the whole Theme Park fanzine in this gallery...

The Uxbridge Road: The Exorcism of Boris Johnson

Posted in London on Saturday 7th December 2019 at 10:12pm

I don't believe in magic. That said, there is a strain of mysticism which seems to synchronise with the practice of walking. The ancient lines which are inscribed in the land, though buried beneath asphalt and brick, are present for reasons we'll likely never entirely know. But sometimes they are closer to the surface, and part of the reward for walking in London is the frequent sense that time is stretched and thin, uncovering these old ways. While that sense is invariably present in the ancient precincts of the City, surrounded by the remains of the Roman and Mediaeval, it is often strongest in the suburbs where it doesn't need to compete for attention. Out here on the fringe, there is a thinner layer of overlaid civilisation and the ancient tracks are closer to the surface. While I'm more accepting nowadays of the unseen and uncanny rather than the downright magical, I'm sometimes equally sceptical about the political world. That said, John Rogers has written convincingly about the revolutionary power of walking, drawing together the threads of high-minded European theory and resolutely muddy-booted British practice. While the pioneers who kept Britains' byways free for rambling and trekking were fighting a battle against ancient baronial land rights and sometimes an overbearingly elitist state, the idea of walking for leisure remains a solidly middle-class pursuit practised mostly by those of us with an excess of time and resources to spend on it. Perhaps the most eloquent proponent of the democratic value of walking was the topographical writer S P B Mais, who railed against the cry for 'distraction' and saw walking as a redemptive and recalibrating force. Today, I wondered if I could combine these two concepts, somehow uniting the political and mystical traditions in a more contemporary project? If reconnection to the land could offer health and reason - and if walking was truly an act of democratic expression - then perhaps I could devise a walk to resolve a dangerous and diseased situation in the heart of Westminster. Perhaps I could walk to exorcise Boris Johnson from the political map? If he was victorious he'd head from Uxbridge to London to resume control of the government. Perhaps if I could pre-empt this journey by uncovering the lie of the land along this ancient route, I could somehow tilt the outcome on its axis? It had to be worth a try...

I arrived in the cathedral-like terminus at Uxbridge under uncertain skies. The forecast was dull, dry and mild despite the advance of December. Uncomfortable weather for trying times. The weak winter sunshine barely illuminated Ervin Bossányi's stained glass panels in the clerestory above the lithe concrete struts of the station roof. The arms of Middlesex and Buckinghamshire cast a dull glow over the gateline as I followed a sizeable crowd out into the High Street, turning around immediately to appreciate the exterior of Charles Holden and Leonard Holcombe Bucknell's imposing entrance, flanked by the winged wheels of progress. Uxbridge felt prosperous and busy - a distinct and self-assured market-town which existed firmly outside the gravity of London. A few streets beyond the town centre the Frays River and the Colne Valley marked the edge of the metropolis, administratively at least, but the mood and tone here were already provincial. The train had been busily gathering passengers during the last few stops, and the glassy, modern shopping centres which clustered around the terminus were already busy. Uxbridge was clearly a destination, not a satellite. It had of course been a regionally significant centre for centuries: this was a Saxon market town, named for the Wixan: settlers from Lincolnshire who farmed the fertile Pinn and Colne valleys, likely establishing their settlements where Bronze Age predecessors had founded their villages before the interlopers arrived. The town became a garrison for the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, hosting a summit between King Charles and Parliament which failed to secure a resolution - reportedly due to the King's mistaken belief that military operations were already turning in his favour. As such, the Treaty of Uxbridge isn't the defining event in British constitutional history which it might have been, but the town nevertheless has a long association with the political life of the country. The Crown and Treaty inn where the opposing commissioners met still stands, a rambling red-brick building dating from 1576 but now dwarfed by modern developments which cluster impatiently around it, awaiting its eventual collapse. Uxbridge is also the administrative centre of the Borough of Hillingdon and as I sought the edge of town to begin walking along the road to London, I found myself caught amongst the various and improbable geometries of the Civic Centre. This weird, sprawling building with haphazard jutting eaves and a meandering footprint was designed by Sir Andrew Derbyshire and finished in stages by 1976. The building aims at a British neo-vernacular style, using tile and brick which echo traditional materials in the area. I walked a near-circuit of the outflung ziggurat, passing the site of the former GWR Uxbridge (Vine Street) station, now buried under tarmac and shopping arcade - a Crossrail connection opportunity missed? As a demonstration of its stature and indepdence, Uxbridge once benefited from three railway stations on separate lines - but now just one survives. Aiming for the spire of St. Andrew's church at the top of the rise, I pressed on into the gloomy morning. Uxbridge owes a great deal of its growth over the centuries to providing the first stop on the coaching route from London to Oxford. That road, once the route of the mighty A40, was now relegated to a supporting role - but it still regularly seethed and jammed with traffic pounding in and out of London. The settlements along it were supremely badly connected, mostly sitting some distance from Underground or railway stations which only nominally served them. Several bus routes remained dedicated to plying a linear course along the Uxbridge Road and avoided attempting to serve other areas, so prone is the route to snarling delays and unreliability. Topping the rise near the gold and terracotta brickwork of St. Andrew's Church, I realised I'd climbed out of the valley of the Colne and turned towards London at last. The road ahead led downhill, for now at least, as the carriageways split. On the western side of the road, a range of 1930s villas followed the gentle curve, while the eastern edge was in the process of becoming St. Andrew's Park: a vast new residential development which sprawled along a stretch of derelict light-industrial land. The quarter was slowly growing from the ground, apparently pleasant and low-rise, a modern equivalent of the kind of housing estates which crept towards Uxbridge in the middle of the last century, slowly engulfing it in the metropolis. There was little novel or attractive about this sprawl of housing - but it was at least built to a far more human scale than the clumps of stocky and anodyne new towers which dominated closer to London. Between the carriageways of the gently curving road, a broad swathe of grass hosted mature trees, indicating how this road was doubled in width long ago to cope with the growing traffic of the 20th century. The twin ribbons of asphalt twisted west and south, descending towards the valley of the River Pinn. I picked up the pace and begin my walk in earnest.

The valley bottomed out at the edge of Hillingdon Golf Course which rendered the Pinn's tangled and weed-choked banks inaccessible. The river passed beneath the road via an unremarkable bridge and headed west towards the Frays River and their nearby confluence. The road's edge described the southern limit of the grounds of Hillingdon House, formerly a grand hunting lodge built by the 3rd Duke of Schomberg in 1717, perhaps something of a retreat from his more ostentatious and notable Pall Mall pad completed some years earlier. The Duke, of German Huguenot descent, had served under his father, the 1st Duke at the Battle of The Boyne in 1690, leading the decisive river crossing which largely decided the conflict. For his efforts, he was granted British citizenship by Act of Parliament and later commanded British forces in Flanders and Portugal. While the echoes of the events in Ireland had reverberated through the centuries, Hillingdon House remained somewhat unremarked for many years until it succumbed to a catastrophic fire. Rebuilt as a grand mansion in 1844, it eventually passed into Government hands with plans to build a prisoner of war camp in the grounds during the First World War. Local opposition put paid to this scheme, and the site became a Canadian Military Hospital which remained on site until 1917 when the men of the Royal Flying Corps moved in to found their armaments training school. RAF Uxbridge and the attached RAF Hillingdon - in reality, a single large site divided by the River Pinn - provided a supply base and a tactical command post throughout the Second World War. During the increasing tensions of the 1930s, thoughts turned to how British airspace could be defended effectively, leading to the RAF adopting the Dowding System: by combining radar data and reports from the Balloon and Observer Corps with telegraphic contact to the airfields ranged along the eastern flank of the UK, it was possible to anticipate and respond to the incoming threat of the Luftwaffe. Realising that the wooden surface buildings of RAF Uxbridge were vulnerable to attack, a contract was hastily let to Sir Robert McAlpine to secretly excavate an underground control room, purpose-built to withstand attack and provide an around-the-clock response to enemy activity. The Dowding System proved remarkably successful, slowly grinding down the enemy's capacity for sustained air warfare and effectively laying the groundwork for modern air defence systems. It was following a visit to the control bunker in August 1940, watching the flickering lights which indicated squadrons engaging in combat, that Sir Winston Churchill uttered the phrase "Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed, by so many, to so few" which he later repeated in the House of Commons. Following the Battle of Britain, the control bunker would go on to support defence against the Blitz and to coordinate the air support for the D-Day landings. The RAF continued to use the Uxbridge and Hillingdon sites until 2010, when the remaining logistical and administrative functions moved to nearby RAF Northolt. The site was more rececntly obtained by Hillingdon Council who now operate it as tourist attraction including a modern visitor centre opened in 2018.

Churchill visited RAF Uxbridge on one further occasion during the war - but that hasn't stopped the Borough from co-opting him as a local celebrity and de facto genus loci. His name appeared everywhere as I continued along the road, curving subtly northeastwards towards the suburban fringes of Hillingdon. A road named in his honour formed the spine of a housing estate, while the dilapidated twin nissen huts of the Battle of Britain club decayed nearby, closed when the Ministry of Defence billed the hostelry for rent it had neglected to charge for 16 years. Perhaps it was no accident that when choosing a safe Conservative seat on which to base his re-entrance to Parliament after two terms as Mayor of London, Boris Johnson selected Uxbridge and South Ruislip? His oft-professed hero loomed large over the sleepy edges of Middlesex, preserving a sort of sleepy post-war peacefulness which radiated along the old road towards London. This was the essence of Johnson's appeal: a return to the settled state in which much of suburban England slumbered through the decades after hostilities ceased. A time on which idealised Blitz-bonhomie memories were based. Here in the southeast, where to some extent the hardships of recession and austerity had failed to bite, the urge to leave the EU was less compelling. Those who wanted to secede didn't base their vote on the sense of inequality which triggered it further north. Instead they heard the referendum as a call back to easier, simpler times when people knew where they stood, and most importantly who their enemies were. Memories are long in the suburbs where time moves more slowly, and life is always easier with a shared foe to rally against, real or imagined. The Uxbridge Road was a parallel to this historical self-deception: superceded and no longer the main road, but still a thundering trail of tail-lights and angry metal. The businesses flanking the street looked downtrodden, broken by lack of passing trade. No-one walked here. Hillingdon - meaning the town rather than the Borough - was a place with no centre. The cluster of streets around the Underground station much further north was its nominal town centre, while this ribbon of closed shops, takeaways and newsagents was Hillingdon Heath. An absence of a community. As I trudged the familiar landscape of mid-century development and light industry, I realised that despite a year or more of tentatively walking out here I still had no words for the West. For the east, I'd developed a vocabulary of absence and deletion, much of it shamefully borrowed from brighter minds and more authentic voices. But out here I was alone. The ghosts of long-dead airmen, of fleeting presidential visits by Churchill and of the dying culture of suburbia haunted the Uxbridge Road.

Cowed by the combined forces of ubiquity and mundanity, I sought the purpose to continue east. I thought back to the reason for this strange ambulation and recalled S P B Mais again. He had urged his readers, ultimately perhaps very wisely, to 'eschew therefore any walk that entails any more than a hundred yards of high road'. This walk, in fact, many of my walks this year had been all High Road and little else. I was tired and fractious, I'd absorbed the disturbingly divided politics and was trying to walk them out in an area which felt equally split and unresolved. I sleepwalked into Hayes End - the cluster of civilization which straddles the Uxbridge Road but again isn't any kind of urban centre, requiring a long detour to the south to reach Hayes Town or the railway. In doing so I crossed the constituency boundary - from the Conservative safe seat of Uxbridge and South Ruislip into the Labour stronghold of Hayes and Harlington. The boundary was unremarked at street level, but the shift in tone wasn't lost on me. This strip of retail activity could have been parachuted onto the sides of any of the major arterial routes in London: a run of Tudorbethan gabled shops housing tanning salons, hairdressers, a post office and some minor branches of national chains. Between these, light industrial units dating from the middle of the last century rubbed up against the remaining social housing stock of the Borough. Two properties stood out, both of them across the barrier-enforced central reservation: Lots of Rice - a Chinese Takeaway which set out its consumer benefits with remarkable clarity, and that other stalwart of the pre-motorway high roads: a sprawling red-brick roadhouse - closed of course. This wouldn't have struck me as unusual but for its name. Formerly The Angel, an unfortunate accident had disposed of its initial vowel, and for one dark moment I read it as 'The Nigel'. Perhaps it was the tattered, flapping St. George flags which were developing a coat of carbon, or maybe the general sense of decay of an establishment well past its prime? Disbelievingly, I scraped road-dust from my eyes and spied the vacancy for a capital letter. Thankfully things hadn't gone too far yet, and there was light at the end of this particular section of the grim tunnel as I approached the Borough boundary.

A branch of Premier Inn nestled into a corner of Yeading Lane, the now far less important north-south thoroughfare which led towards Hayes - the place for which the budget accomodation had been named despite its distance. The hotel had cynically added 'Heathrow' to the end of its name in the hope of scooping in a few hapless but geographically innocent travellers. Escaping Hillingdon here meant crossing The Parkway, my recurring western foe, as the Uxbridge Road descended to meet it in the valley of the Yeading Brook. The lie of the land was familiar from my walk along the progenitor of the River Crane, and as I tackled the multiple-stage road crossing via the centre of a wide roundabout which disgorged three lanes of traffic towards me, I recalled just what a confusing zone this was. The brook surfaced in two distinct branches, one which appeared to be a modern culvert providing drainage for The Parkway in its guise as The Hayes Bypass. The other clung closer to the Grand Union Canal which also shared its shallow valley, all three passing under my route to emerge either in the sprawling Lombardy Retail Park or in the tangled scrubby woodland of Minet Country Park. This relatively modern green space was dedicated to the public only in 2003, having until the middle of the twentieth-century been part of the Coldharbour Estate, owned by the Minet family. When I had passed this way in pursuit of the Yeading Brook, I stuck to the towpath of the Canal, somewhat daunted by the confusing appearances and disappearances of the waterway. Now I straddled the valley, awaiting my turn to shuffle across the traffic on the Ossie Garvin Roundabout. Garvin was a long-serving Labour councillor who, after an early move from Lancashire to Hayes to escape the mines and work at EMI, became the Leader of Hayes and Harlington Urban District Council, later serving as Mayor of Hillingdon. Garvin was reportedly never enamoured of the post-1965 borough, feeling that locals of the eastern parishes of the new sprawling authority would lose out in the process of integration. It's possible that he was right in a number of ways, not least that the long struggle to see the town bypassed and traffic gridlock reduced would not end until two years after Garvin's death in 1990. Along with John McDonnell, now elevated - sometimes seemingly to his own surprise - to the office of Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer, he endlessly lobbied the GLC to build The Parkway, both politicians resorting to civil disobedience to press the case. Now the bypass he'd staked a career upon cannoned under a roundabout bearing his name, fittingly marking the extreme boundary of a Borough he served dutifully but never loved. There were however just a few more short yards of McDonnell's constituency left to walk, as it petered out beyond the Parkway at the bridge over the Canal. McDonnell would be returned to Parliament for sure - only a mammoth swing could unseat the stalwart campaigner, though this wasn't always a safe Labour seat. Prior to McDonnell's arrival, the loathsome Terry Dicks had held sway in Hayes and Harlington. Born with cerebral palsy he described himself in the house as 'a spastic'. More recently famous for an unearthed incident where he expressed disdain for the apparel of an upstart Jeremy Corbyn in 1984, he abhorred immigration and openly mocked the unfortunate and disabled, but nevertheless comfortably held this seat until retirement in 1997. Still alive and in his 80s, he sits on Runnymede Borough Council in Surrey, presumably an area which provides him with far less uncomfortable evidence of the immigration and integration which he appears to fear so greatly? The shift from right to left here was more extreme than the pendulum swings in other parts of the city. Something about these rather grey suburban avenues not far from the Heathrow flightpath provoked unease and discomfort. It was no surprise that a mace-wielding McDonnell in vigorous opposition to a third runway would inspire the voter here. However, considering the reliance of the locals on the airport economy perhaps the turkeys would be voting for an early Christmas?

Crossing the Grand Union Canal, I looked down at the spot near the Territorial Army depot where I'd zig-zagged up to street level a month back when an inconsiderate bird feeder had blocked the towpath with a flock of angry swans fighting for scraps of bread. I was now in the borough of Ealing, and walking a string of Labour-held constituencies which would take me into Central London. Uxbridge Road temporarily became The Broadway and the suburban sprawl gave way to the narrow High Street of Southall. The street vibrated with life which had been missing since the centre of Uxbridge. Hemmed into narrow single lanes between street furniture designed to quieten traffic, there were fractious scenes at junctions. Horns sounded, and an ambulance driver nudged and cajoled the traffic into letting him swing off the main road into a side-street. The coming of the Grand Union Canal and then later the Great Western Railway brought industry to Southall, seeing the rural Middlesex fields develop rapidly into a busy zone of factories and works. Martinware pottery, cereals, margarine and animal feed production required a workforce, and as such Southall was a destination for migration from the earliest years of the 20th century. First came a wave of Welsh mining families fleeing poverty in the Valleys, followed by Poles escaping unemployment and Imperial repression. From 1950 however, events would change the character and demographics of Southall entirely. Following the partition of India in 1947 and the passing of the British Nationality Act which allowed largely unrestricted movement to Commonwealth citizens, a steady flow of Indian and Pakistani families began to arrive in West London. While many of the new arrivals were highly educated and skilled, they experienced great prejudice, with their poorly spoken English mistaken for stupidity or ignorance. Many found unskilled opportunities in the factories around Southall, Hanwell and the Golden Mile of Brentford, not least in the R. Woolf and Co. rubber works, run by a former British Indian Army officer who had served in India and was sympathetic to their situation. As Southall prospered and grew, not least due to the need to support the expanding activity at Heathrow Airport, so did the South Asian community, with the area developing to meet their cultural and religious requirements. The result is 'Little India' - the dizzying collision of cultures along the Broadway which sees familiar British chain stores nestled between shops selling jewellery, Halal meats, saris and enticing trays of Indian sweets. The high street bustled in a way that few of the suburban centres around London manage. Proprietors stood outside their premises, surveying the street and calling to each other. People moved through a crush of shoppers and businessfolk, deftly weaving towards their chosen destination avoiding what appeared to be inevitable collisions. I have rarely felt such complete dissonance: tramping out east had brought me to areas built on a palimpsest of immigration, but gentrification had shifted their balance and left them contested. Southall however, was a different world - it was thrilling, enthralling and a little unsettling to find myself so completely subsumed by an entirely different culture to my own just a few steps along the greyness of the Uxbridge Road. It is of course frowned upon to suggest that anything less than integration is possible where immigration is concerned - and that very fettering of discussion is the seat of many current issues - but Southall worked on a different scale. This wasn't about individuals being subsumed into British culture - whatever that might mean in a world where Boris Johnson could be Prime Minister again soon. This was about Southall as a whole being integrated into the fabric of London. It worked, and it had rather shocked me into rethinking my map of the city.