There was just a little hint of the old days - rising early and heading out in the dark to get to the beginning of a railtour used to be a fairly commonplace happening. But today it felt like something of a rarity - and I surprised myself by being pretty excited about the trip despite the early hour. After a quick walk from Hoxton to Liverpool Street station I boarded a No. 11 bus which soon set out across the dark, quiet City of London. As we snaked between the Bank of England and St. Paul's Cathedral, only the very earliest denizens of the streets were out and about. These days between Christmas and New Year, while technically working days, were clearly not going to see a lot of business transacted and the financial district had more cleaners and dustmen than money-launderers in evidence today. The bus swung south from the Strand onto Whitehall, passing Downing Street and heading for Parliament. I was almost sorry when the impromptu tour of the awakening city ended amidst the building site fronting Victoria Station. I was less sorry to have the chance to get coffee though - and despite a bizarrely misunderstood part of the transaction when I incidentally asked if their was a Post Box nearby, I was happy to be served a large steaming cup of coffee and to sit watching the vast station beginning to bustle with incoming commuters. Among them though, a different crowd was evident: eagerly flitting along the gateline, heads arcing over the crowds for unit numbers, backpacks bursting with nutritionally questionable snacks for the day ahead. The Neds were arriving! Forced to concede that I could pass as normal no longer, I joined the procession to Platform 2 where our train waited. These, after all, were my people.

We were soon underway, emerging into a day which had dawned surprisingly bright but still frosty. The route took us around the familiar loop of the North London Line to Stratford where colleagues joined for a sociable day on the rails. From there we headed out into Essex, using the connection to the London Tilbury and Southend railway at Forest Gate to cross into very familiar territory to me. As we scudded over the flat marshes around Rainham and out into the borderlands of Purfleet I spotted locations from my perambulations alongside the tracks - small, insignificant details to the wholly railway-focused bunch on board, but immensely satisfying to me to see how my wanderings had joined up this territory. From the train I glanced down at the broad green walkway beside the Mayes Brook from my most recent ramble, and wondered if the old gent and his dog were out this fine, frosty morning watching our unusual train speeding east? Peeling away from the mainline west of Stanford-le-Hope our first call was at London Gateway - the vast, and still growing, new container port at Thames Haven. My last visit here was to a largely derelict fuel refinery, sitting close to the estuary waters. While some of this landscape remains extant, the edge of the river is now a vast plain of concrete stacked with containers and presided over by computer-controlled cranes. Our train drew along the arrival line, as far as we could practically travel - while beside us the cranes continued their work. Few other humans could be seen aside from the crew of our train walking back to reverse out of the complex. It was a strange mixture of impressive and oddly creepy here.

Reversing, we headed back to Grays where again I could see locations from my still-to-be-completed A13 walk. Another reversal took us back towards Tilbury Town, then onto the curve towards the former Riverside station. It seemed odd that this somewhat anachronistic location closed to passengers as recently as 1992 - now serving as the terminal for cruise ships, but still providing the boarding point for the ancient Gravesend ferry. This was where the former British Empire washed against the island's shores - bringing subjects looking for a new life to London and beyond. A point of arrival, but of departure too with the shade of Joseph Conrad and Dracula haunting these reaches of the river. Now it was a forlorn spot - the building separated from the tracks, and the rails serving only a small container depot. The Thames lay out of sight, beyond the clock tower bathed in strong winter sunshine - but it could be sensed and smelled too. A further reversal took us back to Tilbury Town, passing alongside it's beleaguered and tired High Street, and then retracing our steps through South Essex. I realised as we passed through the flat marshland, running parallel with the A13 on its low viaduct, that this area had become a place I felt strangely attached to over the past years. I felt oddly comfortable out here in a place which, on my earliest passings by train, had felt strange and bleak.

Retracing our loop around London, we passed under the line we'd used to depart from Victoria and into the complex network of lines serving North Kent. A recent inspection of the allegedly temporary bridge which had been swiftly installed by the British Army following the disastrous Lewisham Rail Crash in 1957 had left it impassable by locomotive hauled trains, and while it looked like urgent work over Christmas may have remedied this it was too late for this trip which had been replanned to work out to Swanley and effect a complex reversal between two closely-spaced signals. This was managed professionally and we were soon heading east again to Hoo Junction via the rather uncommon Lee Spur. The afternoon shadows were growing long, and the desolate Hoo peninsula was bathed in a golden light as we took the now freight-only line towards the Isle of Grain. The landscape was flat and marshy, riven with creeks and inlets. The tiny settlements on the island were out of sight entirely, only the cranes of the now quiet Thamesport on the horizon. We halted for a road crossing before passing the site of the former branch to Allhallows and creeping forward towards Grain Old Station where we halted for the Fire Brigade to top up our water tanks as the sun finally began to set. Looking south, the tall bridge connecting the Isle of Sheppey with the mainland could be seen catching the last golden flecks of daylight as we prepared to reverse and head back to London.

It's been good to get back out on the rails this year - but this trip was rather special with it's traversal of territory so close to my area of interest and so connected to my reading, writing and thinking in recent times. With good company, a well-planned itinerary and trip which actually pulled off all it set out to cover, it turned out to be fantastic day. I even managed to avoid waxing too lyrically about the estuary and the territory we covered I think, but perhaps my tour colleagues should be the judges of that!

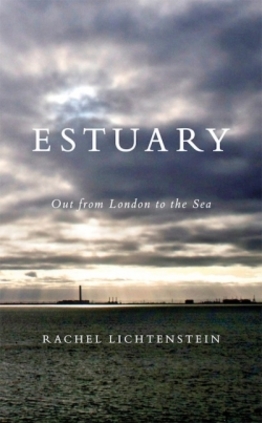

Over the past few years, as my explorations of the Thames have taken me further and further eastwards, I've begun to appreciate the estuary in a different way. It's fair to say that, until recently, the wide expanses of flat empty land almost terrified me. The broad sweep of silver sky broken only by marching ranks of pylons seemed endlessly and bleakly awesome. But it has also always drawn me - the edges of London blurring into the post-industrial wastelands of Essex and Kent are curiously intriguing to me. Haunted by Joseph Conrad and Bram Stoker, and never far from the weird rural gothic of rural eastern England, these white spaces on the map of the British Isles dared me to fill them in with detail. Rachel Lichtenstein's account of her own curious relationship overlaps with mine, but her gaze is firmly eastwards. Having grown up in Southend-on-Sea where the broad mouth of the river opens into the North Sea, her fascination is strongest when considering the remote forts which stride ominously across Shivering Sands, or the treacherous muddy reaches which can strand a cockleboat for hours during slack tides. Those familiar with Lichtenstein's style will be comforted - she writes primarily about people in the context of place, and the social history of the river and shore is never far from the forefront of her prose. She finds the families who trace back their generations in Thames Barge pilots, the women who have lost husbands to the unforgiving tides, and the eccentrics who choose to live out on remote broken outposts in the river - whether for art or solitude.

A theme worming through the book is the impact of the vast Thames Gateway port near TIlbury. This is variously described to her as an imposition on the delicate ecosystem of the river and a necessary evil to keep the seamen and dockers at work, even in now greatly reduced numbers. The impact on the lives of fishermen and their families, wreck-hunters and navigators of the complex estuarial sand bars is carefully catalogued. The sense is that no-one really knows how it will change the topology of the river despite mathematical modelling and careful studies, and this is echoed in the uncertain future faced by the people who live beside it. Lichtenstein is careful to tread the documentarian's path here - she hears and retells the stories, but doesn't wholly pass judgement. The estuary has changed immeasurably over the millennia - and her book is just a sliver in time, describing the latest shifts and changes.

Early in the book, Lichtenstein notes that little has been written about the Estuary as an entity - perhaps because London draws the heat? She interrogates the few sources available carefully, weighing their sometimes quaint historical evidence against what she hears from those who currently live and work here. While it appears true that few factual accounts focus on the estuary, she engages with those who have woven it into their art - not least with Iain Sinclair who trails the river east in his meta-fictions Downriver and Dining on Stones. He joins her at Tilbury Riverside, the former port and railway station where immigrants from the Commonwealth and beyond would arrive in the UK and commence their journey west to London. Her work with Sinclair here - and in earlier shared projects - has been neatly complementary. His topographical and historiographical work meshing with Lichtenstein's social history - bringing his sometimes breathtaking and overwhelming occultism down to a human scale. Together here, they play off each other's interests - Sinclair considering the tide of humanity arriving on these shores, while Lichtenstein looks for eerie geographical features - the stranded masts of the SS Richard Montgomery are unpredictable, decaying fuses signifying the knife-edge on which the estuary sits: politically, culturally and environmentally.

For me, and for other topographical obsessives perhaps, the book feels incomplete - the sinister reaches of the Thames between Purfleet and Greenwich largely unexplored for example. But for Lichtenstein the work is complete - bookended by two journeys: one a dangerous excursion which makes its mental and physical marks on her, the second a redemptive but still incomplete unravelling of the first some years later. In that sense Lichtenstein's broad descriptive sweep and sometimes unfocused prose style are perfect - this is a reflection on a season of life where the estuary haunted her. It is a reverie and an exorcism as much as a social history. A book focused on this very territory was always likely to draw me in - and while covering such an ambitious sweep in a personal account like this didn't feel entirely satisfying, it's certainly one of the finest books written about this weird and remarkable part of Britain. Given how the blank Essex skies often feel like an unpainted canvas, I suspect that anyone who has walked the shoreline will only ever be satisfied with their own version of the estuary. For now, this is a fine proxy.

I'd worried all week about whether my new winter coat would arrive in time for this walk. Commuting to work in sub-zero temperatures during the past week had alerted me to the simple fact that I was ill-equipped for a December jaunt, reminding me of the cruel winds which whipped around me as I strode out into Essex at the end of last year. I'd half-heartedly planned several potential walks - and I was prepared to change my plans and have a day of train-related travels if the weather turned ugly. However, the coat arrived and as I rather snugly skittered out of Liverpool Street on a local train, I realised that a decent pair of sunglasses might have been a more pressing purchase for today. As we snaked across onto the fast lines and sped out towards the east, the low winter sun glared into the windows, glinting from the cranes which surrounded the edges of the Olympic Park at Stratford and throwing long shadows from the half-built towers of East Village. It was a relief to be moving - the last few weeks had been challenging and felt like a hard slog at work for both of us, and the chance to get pavement under my boots again was welcome. The half-formed plan which I'd settled on was to return to a place I'd formed a perhaps unfairly poor impression of to start my walk: Chadwell Heath. I was on the trail of the Mayes Brook: a tiny waterway which rose hereabouts and meandered south and west towards the River Roding at Barking, forming along its course the perimeter of one of the most significant public housing schemes ever built and providing a boundary between boroughs for a good deal of its length. I'd crossed the tiny but significant brook on my A13 walks, found it interesting and wanted to explore further. That walk though had a clear purpose, so I had to content myself with laying down a marker for future travels. It was curious how these furthest eastern expanses of London, which had seemed both a formless suburban sprawl and an almost troublingly dark place at first, were now filled with these streams and byways which I felt an urge to understand. I felt like I was slowly coming to know the territory, pieces slipping into place as streets were crossed and re-crossed, the edge of my ever present range anxiety slowly pushed back towards the coast of Essex.

My return to Chadwell Heath did a little to soften my previous opinion. On a bright winter morning, the walk down from the station to the long straight High Road to Ilford was pleasant, and while the street was still a collection of enterprises barely hanging on in their crumbling mid-century parades, it was a least a little more cheery. On the corner where I joined the main road, the imposing 1934-built Embassy Cinema building had become the unspecific 'Mayfair Venue' - apparently a banqueting suite in a somewhat unlikely spot. Across the street, the urban centre petered out into a long run of domestic appliance repair centres, used car lots and the apparently ill-starred 'Tranquility Centre' - formerly a tropical fish emporium. My target was an unpromising alley beside a petrol station which led to a bridge over the rails I'd just travelled. As I reached the top of the bridge the sun crested the low roofline of the houses and the scene was surprisingly illuminated from the south. Shielding my eyes I picked my way along the path leading to Green Lane and the entrance to Goodmayes Park. The park opened out into a broad sweep of green with a glassy black lake stretching along its eastern side. Through a broad refuse trap, and behind a boom restricting pollution from entering the carefully cleaned up lakes, the Mayes Brook trickled in from its source. The park was quiet, with a few distant joggers and dog walkers crossing the bridge which separated the upper and lower parts of the long lake. Straying from the path I took the well-worn gravel track which edged along the water, and from the southern tip of the lake I looked back at where the brook entered the lake. So little of the short waterway is above ground, making these occasional glimpses precious. Turning south again I headed out of the park by crossing Mayesbrook Road - one of the few nods to the presence of the stream here. Looking east, the uniform houses marching into the distance marked the western edge of Becontree - when completed in 1935 the biggest municipal housing development in the world. Straddling the Boroughs of Ilford, Barking and then remarkably rural Dagenham, the estate was extended twice before finally being fully absorbed into the new borough of Barking and Dagenham. From the air, the streets fall into regular patterns of straight crosses and fans of stacked crescents. The rails that once ran along Vallance Avenue to carry building supplies the estate are long gone, and the vast estate now relies on the spreading arms of the Great Eastern Railway and the District Line which it sits squarely between. Crossing another street I enter the unimaginiatively named Goodmayes Park Extension - a broad sweep of close-cropped grass divided into football pitches, with an allotment on the western flank. The path edges around the pitches, skirting around a range of pavillions and changing rooms painted a drab municipal green with windows fully boarded up. Somewhere under here, the brook runs south and west, towards Goodmayes Lane. Above the tree line a formal facade and clocktower indicate the site of South East Essex Technical College - latterly the University of East London. Built to provide education for the new population of Becontree who were inconveniently split across three Local Education Authorities, the campus survived until 2006 when UEL rationalised its estates and these imposing buildings were redeveloped as housing. The main block is named Mayesbrook Manor - the water, it seems, is never very far from the surface.

It's only a brief escape from parkland - long enough to navigate the junction of the busy and broad A124. I find a small corner store here and buy water. In my urge to get moving today I've neglected the usual preparations, and the walk so far has been surprisingly warm. Across the street I see a tell-tale patch of reeds behind green railings. Looking down from the street Mayes Brook trickles slowly between carefully reinstated habitat, a wild thatch of grasses beside it waving in the breeze. Beside the nature reserve a grand gateway opens onto a broad pavement leading into Mayesbrook Park. The line of green space which runs along the course of the brook - whether present above ground or not - is almost unbroken, and I'm soon walking a broad grassy trail close beside the stream which flanks Barking Football Club's home ground. A vast modern sports facility fills almost the entire width of the northern part of the park and through the trees and fences I spy a lurid purple splash with a familiar angular font - this is another London 2012 legacy artefact. That said, the sports centre appears well-used this morning, and the ranks of football pitches which spread south into the park are equally busy with games formal and otherwise. I stick to the western fringe of the park where the brook curves through new drainage swales and wetlands, created to cope with the ever-troublesome waters of the brook in flood, an event anticipated to be more frequent and dramatic as the earth warms. An arm of the brook passes under a squat bridge with a low brick parapet, draining into the broad lake which fills a former gravel pit. These pits were originally separated by a long narrow causeway leading to a broad circle for turning the plant which dug and carried gravel - this is reputed to have given the park its local name: Matchstick Island. The park was planned on a grand scale - its sporting facilities matched by sunken lotus gardens and stepped verandas. The newly transplanted inhabitants of the Becontree and Leftley Estates would enjoy the fruits of inter-war municipalism until the 1980s when a lack of repair and vandalism led the Borough to remove the sunken gardens. The lakes remain, with the carefully planned wetland course of the brook curving around them to exit the park under the District Line. I lingered in the park for a while watching Canada Geese massing on the wide concrete slipway into the lake. I could have hung around longer too - It was a perfect morning to be out here, and there was an uncertain distance to go - so reluctantly I pressed on out of the park into a place which doesn't exist...

Railway station names are not nearly as fixed and unchanging as they might sometimes seem. In London most especially, the plethora of competing companies operating independent lines prior to nationalisation made for a confusion of names - often similar though relatively distant - in order to attract the lucrative commuters who sought a haven away from the city. Sometimes multiple stations co-existed confusingly with the same moniker - the multiple West Hampsteads which straddle the road north from Kilburn even today for example. As the fortunes of suburbs fall and rise and fall again, their stations names are extended or curtailed according to popularity and reputation. Equally, as the railways struck out into undeveloped territory during the Victorian and Edwardian building booms, the stations took on the names of wayside inns, manor houses and hamlets which have long since been swallowed by the ever-encroaching edges of the city. In this way there are many suburbs and districts of London which have grown around and subsequently adopted the name of their nearest railway station. But I realised as I stood outside Upney Station that there really isn't an Upney at all. The station is an unremarkble low-rise brick building straddling a road bridge in the style of many at this end of the District Line. Atop the building a spike pierces a large Underground roundel, the bridge extending beyond the building to cross the mainlines to Southend. I was now walking along Upney Lane - in traditional British nomenclature the road to Upney - and on the tiny parade of shops at the edge of the estate was an Upney Fish Bar - but that was the only hint of the name on the ground. On my OS map, and even on Google's map which is often tainted with unofficial user contributions, the area had no specific identity. It was a hinterland of Barking - or perhaps a premonition of Dagenham depending on your viewpoint. But it wasn't Upney anywhere. My stay in this ghost suburb was brief - but for good reason. Across the bridge, and just a few steps to the west was Eastbury Manor House. The house can't easily be seen from the north or east due to a rise in the land - and it seemed unlikely that I was approaching a survivor of Elizabeth I's reign as I tramped around the carefully laid out quadrant of an inter-war housing estate. The quiet streets were full of the smells of lunchtime cooking and still-ticking off-duty cabs. But suddenly the square opened out and beyond the wintery frame of empty branches, a tall brick manor house stood in contrast to the municipal housing around it. Now managed by the National Trust, Eastbury was built on high land which provided fine views across open country to London and the Thames by Clement Sysely probably around 1570. Its situation now is changed - but the sense of being at a high point remained as I walked the boundaries of the square of land in which the house sits. The tall ranks of chimneys and the surviving octagonal turret towered over the pleasant little council houses ranged around it - and it seemed an unlikely survivor. When housing was scarce and the modernising spirit strong, so many places of interest were bulldozed in the name of progress. But somehow, at Eastbury, the wonderful hall has survived as a museum and venue, open to the public at times. The name survives too in the Council Ward of Eastbury - and perhaps in truth that's why Upney never caught hold here? The ancient manor has prevailed in more ways than one.

I emerged from the deleted suburb of Upney at Ripple Road, where the old course of the A13 turns south east to head for Dagenham. The Mayes Brook surfaces again from beneath the gloomy slab block of Sebastian Court, passing under the road and emerging beside a wide strip of well-walked grass. An Environment Agency gate prevents vehicle access, but appears to allow pedestrians to walk alongside the brook here. The sun was bright and low now, and it was difficult to see far ahead - and near impossible to take photographs. I spied someone standing near a bush up ahead and trod carefully - the edges of the grassy path were strewn with the usual edgeland litter - the ubiquitous Polish lager cans, blue convenience store carrier bags, blackened fire-circles. As it turned out, two dog walkers were conversing on opposite sides of a mound of brambles. One of them moved on passing me by, while the other, a while haired older man with a muscular and enthusiastic Staffordshire Bull Terrier, hailed me: "I'm letting him off the lead. OK?". I replied that I wasn't with a dog, but I suspect my unease was still evident from my voice. He told me not to worry - he was a good lad, and just happy to get a run. There weren't many places in easy range for a good run, not which an 82 year old could get to anyway. I strolled along the edge of the brook chatting with this unlikely companion, the water trickling quietly beside us and almost eclipsed by the growing screech of the unseen but nearby A13. He had lived here on Ripple Road for over 40 years, and in Barking for almost his whole life. He'd leave if he could - but he felt he was too old for the stress of upheaval. Certainly, he envied me living in Somerset: "By the sea, eh? Lovely". Much had changed here, he thought - but lots stayed the same. It had always been tough - always a challenge to get on. The Asians earned his grudging respect - buying their properties and extending them, letting out rooms, moving out into Essex on the back of their investments. He didn't dislike them but he didn't trust them or the changes their now overlarge houses made to the area. The new wave of immigration from Eastern Europe troubled him more - the litter, the ruined green spaces, the lack of any sense of integration all worried him. He'd clashed with the young men throwing needles and leaving torn cans in the grass and they'd been rude and abusive - he thought the muscular, moderately wild-eyed but basically docile creature he led along the brook had saved him from trouble more than once. His quiet intolerance was fiercely practical - not motivated by politics at all. While it felt odd and discordant to be speaking in these terms so alien to my own view, he was clear that no political party had it right. The working class parties couldn't talk immigration without tangling themselves in guilt, and UKIP felt like Mosley's bully boys who were still an East End folk memory for his generation. We found ourselves at a steel palisade fence which fully blocked access into a broad green field bordered by the brook, the railway and the concrete viaduct carrying the A13 above them both. I didn't expect to get beyond the railway - but I'd hoped to get closer to the bridge. My companion told me that this had been installed after a group of travellers had parked on the field. The Environment Agency had sequestered the land after an expensive clean up, and dug a deep depression into the field to act as additional drainage when the Mayes Brook flooded. We turned and walked back - another access, through the rear of some former garages was also gated, the structure of the missing buildings clear in the concrete divisions on the wall. He told me the local residents had taken action, clearing the wreckage of the old garages and painting out graffiti. He felt that the locals did care about their area, but they were fighting a losing battle. We parted at Ripple Road - he headed homeward to watch an afternoon of snooker, and I turned east to get to the A13. I wondered about this man and his experience of change - a force which he couldn't control and had to simply accept - and marvelled at his oddly serene attitude to being overwhelmed. He was clear - the market hadn't failed him, it had simply not touched him or his fellow residents here. It's easy to condemn this generation with their almost casually inherent bigotry and their foolhardy referendum votes, but perhaps sometimes it's prudent to engage - to see this strange and complicated landscape through eyes which have seen its rise, fall and abandonment. I felt privileged to have walked a little of the brook with someone who'd known its journey.

I stood rather distractedly at the apex of the junction, finding myself reminiscing about my previous visit. Trucks clattered onto the lower spans of the Lodge Avenue flyover ahead of me, and behind me a complex transaction was going down at the car wash, unfamiliar accents prattling angrily at each other, hands sliced down onto palms to seal the deal, ancient flip-phones clicked open. I felt comfortable here on the A13 - I knew this stretch of road well and oddly, held it in an almost fond regard. The downtrodden exterior of the Thatched House sat behind the familiar high metal fence in defiance of the latest Police application to curtail its opening hours. I turned west, climbing over the bridge and looking back over the brook. Below me, the path I'd walked with my elderly companion stretched away northwards, the chimney stacks of Eastbury Manor House red and tall against the pale blue of the sky. Now I knew the house sat there in the midst of the sweep of the estate, it was hard to miss its incongruous intrusion on the skyline. The sun was low on the western horizon, and I felt oddly close to the City despite it being a smudge in the red distance. I felt connected to the road, and wanted to walk it back to the towers of London. Instead I followed a staircase down from the parapet and followed a tunnel which burrowed under the A13. It wasn't clear if the tunnel had been bored through the concrete, or if the iron rings which lined it were an engineer's affectation. I emerged on the edge of the Thames View Estate, Mayes Brook slipping into view from my left and crossing under the path. From here I could ascend to the road again and walk the London-bound carriageway which slowly returned to earth alongside the brook up ahead. I knew what to expect at the junction with River Road - the brook slices under the street at an oblique angle, the bridge acting as a tidal sluice before the junction with the River Roding on it's final contortion towards the Thames. I crossed the street and reacquainted myself with the final accessible stretch of the brook - a deep concrete channel shored up by crossbeams. I navigated through the knot of streets of suburban housing which filled the space between here and the river, but couldn't get close to the outfall, which sits behind a private wharf. A fruitless excursion to the gates of the plant hire company which now occupies the space soon showed there was nothing doing. High security fencing, a locked gate and a guard post with no personnel. I headed rather forlornly back to the road and began to climb the slope which carries six lanes of traffic soaring over Barking Creek. Looking across the narrow stretch of land which separated me from the Thames the sun glinted off the silvery water and the metallic warehouses, ahead the Barking Barrier towered shadowy and black against the bright afternoon. I set off at a fair pace despite my tired feet - I'd set my sights on Canning Town as a perfect ending point, but it seems oddly distant. As my walk unravelled the sights of a prior journey I felt I'd begun to know the road better - a brief pause at the massive Beckton Sainsbury's then off again, passing the almost hallowed site of the Alp and into the golden sunset which was descending over the City, picking out the disconcertingly slender lines of Balfron Tower and the distant, silly tangle of the Orbit at Stratford. My walk had felt unplanned and insubstantial at the outset, and seemed unlikely to be a satisfying route. But somehow it had turned into an epic and oddly ritualistic unravelling of my year - of walking the eastern fringe and pushing out of the city, using the streams and waterways as a means of reading the terrain. There are still rivers to walk, old paths to resolve - but for now, at least, it was time to turn for home.

You can see a gallery of images from the walk here.

London's Green Fringe: The River Ingrebourne

Posted in London on Saturday 5th November 2016 at 10:11pm

I stood, shivering at the bus stop in the middle of a group of mildly disgruntled passengers. We'd been here for a while, despite being told that the replacement bus service was 'just around the corner' several times. A Transport for London employee conversed urgently with a representative of Ensign Buses who was nervously checking his smartphone screen frequently. A light drizzle started to fall. I hadn't begun my walk yet - but I was already close to turning on my heel and heading back to the city. It hadn't been a great start - the slow slog along the alternative route from Bath to Paddington had been a minor irritation - arriving a half-hour later than usual in London was tolerable in itself. I also knew that the line from Liverpool Street to Shenfield was closed for platform lengthening work - and I'd factored that into my plans. I'd be putting boots on the ground much later than I'd usually plan to be, but if I pushed through the range anxiety which a late start causes, I could still manage the planned route. I'd even managed to commit an annoying cold to the back of my mind - I was still coughing furiously at times, but considering I'd only been nursing the symptoms for a few days, I felt surprisingly ready to tackle a walk. But now I was stranded in Chadwell Heath, an unprepossessing corner of Greater London which has Essex aspirations but none of the means to back it up. A bus finally lurched up to the stop - but another train had arrived now and a stream of passengers ambling along the footpath broke into a trot at the sight. Those of us already at the stop crammed desperately onto the double-decker the moment the last straggler had cleared the decks. The bus was warm and reeked of wet coats and over-deployed aftershave, its windows dripping condensation already from the fresh crush of humanity on board. We set off through the long sprawl of takeaways and suburban pubs towards Romford where the bus mercifully decanted most of the passengers. A few of us soldiered on east - along the curiously named Squirrels Heath Lane towards Harold Hill. This is where I would start - at Harold Wood station on the very fringe of built-up London, an area which until 1965 was resolutely part of southern Essex and has continued some of the less savoury traditions - not least the curiously violent history of the area, with numerous unrelated murders and attacks over the years. Now, it's on the up again - the large swathe of post-war residential areas is improving and the little parade of shops outside the station was busy and varied. A local initiative known as Harold Hill Ambitions oversees the regeneration. For now though, my own somewhat humbler Harold Hill ambition was simply to start walking. Later than I'd like and still with some concern I'd struggle to complete the route today, I headed up the slope by the closed station where a long bus queue was developing for the next heaving double-decker to Chadwell Heath. It was time to set off in earnest.

Once I'd set off and settled into the welcome rhythm of walking, my mood improved. I'd almost forgotten the purpose of today's walk - to chart the course of the tiny Ingrebourne River, one of the easternmost tributaries of the Thames to run through Greater London. It begins its surprisingly long journey out in Essex, on the fringes of Brentwood where it meets the Weald Brook before turning east, passing under the M25 and skirting Harold Wood. I'd looked at the possibility of starting my walk further out near the Motorway - but transport beyond the railway was sparse and time was now a limiting factor. Instead, I turned east after crossing the railway into the quiet backstreets of Harold Wood. A corner store selling car paint was decked out with England flags and UKIP stickers and I fought hard to push the preconceptions away. Here on the fringes of London lies this outer band of economically challenged but just-managing communities which edge a vast city of diversity and change. It's unfair to characterise this as an Essex phenomena - the halo of intolerance circles the city. But here on the eastern edges it sometimes feels more concentrated and close to explosion. I turned onto an unadopted gravel road which ran between lines of suburban semis and allotments. A bonfire crackled beyond the fence, while a group of dedicated diggers prepared their plots for winter. At the end of the track I was deposited onto a surprisingly busy minor road - the continuation of Squirrels Heath Road as it headed over the edge of London. A little to the east a low brick parapet gave away the location of the Ingrebourne at Cockabourne Bridge. The brook was bright and clear here, running over a stony bed and between green, wooded banks. To the east, Shepherd's Hill rose into Essex with a string of car headlamps shining in the gloomy morning. I zig-zagged across the lane and into a narrow driveway leading to Harold Wood Park, before turning east and finding the line of the Ingrebourne beyond the changing rooms and tennis courts. A path crossed the river and turned south - I took it and suddenly found myself out of London entirely. The city felt impossibly and completely distant. The air was clear and quiet, and the sky was a band of grey with a promising flash of blue beyond. As I walked, following the twisting course of the river in its green trench, I realised I was entirely alone out here. The dog walkers had evaporated away towards the car parks, and the only sound was the satisfying crunch of my boots hitting the path on the edge of the woods. I let my pace slacken a little, enjoying the sense of isolation and savouring the pangs of uncertainty which always hit when I feel I've left the gravity of London involuntarily. The morning was surprisingly mild and was staying dry. I wasn't sure what I'd expected of the tiny Ingrebourne but this was a surprise.

As the Forestry Commission's well-maintained path divided I was faced with a choice: head west, and leave the course of the river to detour into more urban territory before regaining its route, or to head east and stick a little closer to the water. I turned east and soon found myself on the busy rat-run of Hall Lane. Despite being a relatively minor and almost rural route, this lane provides a back route between the suburbs of Harold Wood and the larger urban centre at Upminster, crossing the busy A127 Southend Arterial Road at a sprawling junction. The brief section I walked was busy with vehicles but thankfully supplied with a decent footpath. The lane rose gently as I walked south with farmland to the east, and a view over the surprisingly deeply carved valley of the Ingrebourne to the west. Across the valley I could see the distant spire at Hornchurch and stubby towers of housing dotting the hills towards Romford. It felt odd to be looking in on London like this, seeing it as the next village over the hill. A growing hum proved to be traffic on the A127, carving in from the east in a deep gully with sweeping slip roads joining my route here. I climbed the curving path beside the litter-strew bank to find myself above the main carriageway. The rush of traffic was oddly exhilarating after the silent countryside, and the views towards the west suddenly revealed the distant misty shades of London's city skyline which felt alarmingly remote. After descending from the overbridge my path left Hall Lane briefly to skirt the access drive to a row of large, very expensive looking villas with a range of luxury cars in their drives. The link between the wealth of the distant city towers and the assets arrayed along this quiet lane was suddenly very clear and very direct.

The footpath along Hall Lane was officially part of the London Loop path, which I'd find myself following fairly faithfully from here onwards. I was a little ambivalent about this - my walks were supposed to follow the topographical and historical pathways I was curious about and I met all too many people who were set on covering the various mapped and signposted footways around Britain as something of a ticking-off exercise remote from any local interest. I'd been asked "are you doing the London Loop?" often enough to somewhat shudder at the rather glib, middle-class 'in group' of walkers who hefted their poles and wore designer ski-wear to navigate paths within the M25. I also imagined that the London Loop was, like much of the Thames Path, a greatly improved and well-appointed route which would be busy with walkers at all times. This wasn't always what I wanted, and I'd grown used to solitude on these rambles. My experiences over the next hour were to challenge all of those assumptions - and to diminish some of the snobbery I'd somehow found myself deeply mired in, exchanging it for honest English mud. I left Hall Lane to gingerly totter down the steep hill of River Drive. This was a street of fine mid-century houses which climbed down the steep edge of the Ingrebourne Valley between vintage lampposts to meet woodland at the end of the cul-de-sac. When I reached the bottom I squeezed through a narrow gate with a London Loop marker on it, and plunged deep into woodlands. The trees closed over me, and the floor was a sea of autumn leaf-fall. It was eerily quiet and pleasantly cool as I pressed on, thankful for my good boots and treading very carefully over the buckling roots of trees which crossed the path. For a good distance, the path was only a footstep wide, my left boot splashing into a shallow stream which had carved deeply into the muddy ridge on which my right foot was determinedly plodding. I realised that this was some unmarked tributary of the Ingrebourne, which I was soon to cross on its own narrow wooden bridge. The river was still flowing fast and clear here - a reassuring presence after a rather sudden venture into wilder lands. My path continued, sweeping to the south and into a field of horses which I assiduously avoided. Looking back, the rising woodland sloped away into the distance, back to my starting point at Harold Wood and beyond. Ahead, the still remote church tower slipped across the horizon as I edged around recently harvested stubble-fields on a rough and narrow pathway. This was more challenging than I'd imagined my walk, and much less 'improved' than I'd suspected the London Loop would be. Oddly though, I found myself entirely enjoying this surprisingly rural edgeland ramble. I could see the built-up fringes of Upminster beyond a distant school field and the rough walking was exhilarating. I left the path to stalk through some longer grass to the river's edge, speculating that this would have been tougher going in the Summer as I trudged over decaying nettles which would have been a waving field of potential stings just a month or two back. Eventually, the footpath ended beside an allotment and turned a corner into a litter-strewn gravel drive between some concrete garages. While I was sorry to leave the open fields behind, I was hungry and flagging a little, so civilisation was almost welcome as I navigated the backstreets to Upminster Bridge with its little cluster of shops around the penultimate station on the District Line. I grabbed a snack and headed over the river once again at a noticeable depression in the road which marked its valley.

I was eager to find the Ingrebourne again, so I swiftly turned south into the quiet of Bridge Avenue which skirted the edge of Hornchurch Stadium, home to the local football club. The footpath I needed to pick up ran through the club's almost deserted gravel car park, entering a public park via a low gate and becoming Gaynes Parkway - a long, green route through the edges of Upminster which followed the river tightly. After a pause for lunch in the park on a convenient bench, it was good to be walking at some pace again. While the scramble through the woods had been surprisingly good fun, it was slow going and I'd begun to feel the pressure of time again. I recalculated the spots I could practically turn aside if time was short - but there were rather few from here onwards, and striking out for Rainham was by far the best option possible. The path was deserted in the grey afternoon, and I was able to stay close to the meandering Ingrebourne for a unusually long distance as it tumbled over weirs and through concrete channels designed to calm its flow when in spate. As the view broadened into a wide sweep of grassland to the east, the river divided into a number of channels and unnamed tributaries. The Ingrebourne's final stretch is a lazy wander through the flat bottom of a broad valley, where it spreads to feed wetlands and marshes hemmed in by higher ground. Much of the area has become Hornchurch Country Park, largely centred on the former RAF Hornchurch. This was the home of the squadrons of Spitfires which valiantly defended London's skies during World War II, but has a longer link to aviation. A giant iron RAF roundel set into the ground outside the Ingrebourne Valley Visitor Centre is inscribed with the dates of Sutton's Farm - a First World War airfield which requisitioned a large part of a local farm, but closed in 1920 and returned to peaceful pasture. The site was requisitioned once again in 1928 for the larger fighter base which survived until 1962, well into the jet age. Passing up a chance to explore the Visitor Centre and its inviting café due to my tight schedule, I pressed on into the park. A little weak sunshine was beginning to filter through the clouds in broad shafts, striking the wooded hills to the east with patches of bright autumnal gold. The path was busy with walkers, families on cycles and lots of dogs, and it was pleasant to be making a good pace despite tired feet. The former military role of the land was marked by the ominous concrete pill boxes and gun emplacements which were half-buried in grass. Their stark, empty faces now inert but a reminder that this was to a great extent the last line of defence for London. It was sobering to think how London had become a city under siege again back in 2012 and how normal it felt now to see armed police around the city. Strange times sometimes hark back to even stranger eras it seems. Deeper into the park, the stream of walkers thinned and only a few more dedicated souls passed me by. The path took an abrupt westerly turn to skirt the lake at Albyns Farm, dotted with tiny islands which waterfowl flitted between. The path soon turned into a narrow road which led to the farm houses. The impressive houses sat behind high electric gates, an array of expensive vehicles ranged along a rank of large garages, and low-roofed windowless sheds kept locked and bolted. This felt like the kind of spot where you should just walk on and not ask questions - just remote enough to be unobserved, but handy for the M25 when necessary.

I recalled my imagination from its wandering, and focused on my own journey. Here I faced a final choice about how my walk would end - I could press ahead, return to civilisation and walk on pavement to my destination, or I could turn south again via a gateway in the drive, back into the grassland. I opted for the path to the south, which began as a beaten down edge of a broad field which rose slowly to the south. At the western edge of the field it turned through a gate and became a more formal, rough path which continued to climb towards the southern horizon and, remarkably enough today, a sudden break in the clouds. This was Ingrebourne Hill - not really much of a climb, but by far the highest point around for some distance. The tangle of channels and ponds which the river had become slunk around base of the hill, fanning out to supply the wetlands which carpeted the valley. I soon reached the summit and turned a full circle to take in the view. The clouds had parted to let a golden, autumn sunset begin its gradual progress and the farmhouses and fields which I'd walked from the north were bathed in sudden glamour. The trees, climbed away from the valley towards my starting point - a string of distinct but connected green spaces with the river at their heart. If the plans which the London Borough of Havering have tabled ever come to fruition, this chain of spaces would be broken into parcels, some destined for new development. The green belt unbuckled in the east, the city allowed to leak out towards the skies of Essex. To the south of my hilltop lookout the faint line of the Thames shimmered on the horizon while the factory buildings which lined Rainham Creek towered above the range of pylons and mid-rise housing blocks. To the west, a haze blocked the city from view entirely - but to the east the vast plain of low-lying marshland which stretched along the estuary seemed to run on forever, broken only by the slender grey line of the A13 slinking across its vast, green breadth with a trail of red taillights disappearing into Essex. I trudged downhill, towards the road to Rainham.

Despite having another mile or so cover to reach the station, I was confident I had plenty of time. I was moving more slowly now, heading for the Red Bridge at the roundabout where I knew I'd cross the Ingrebourne for one last time. After paying my respects to the river as it began the final twists towards the Thames, I took a different route to the station from my previous treks, walking along Broadway, Rainham's surprisingly interesting village High Street. The squat, businesslike Norman church of St. Helen and St. Giles stood in simple counterpoint to the formal Georgian brickwork of Rainham Hall sitting upright beside the road. Both faced up against a charming street of homes, shops and inns which seemed to tumble together, some of them in the white painted weatherboard typical of Essex. As I approached the station I pondered if I had time to make good on a foolish promise I'd made to myself before today's late start had interfered with my plans. During a tidy of an old piece of furniture we'd retrieved from my parents' home, we'd found a spare set of keys belonging to my mother. I'd turned the wooden 'Scorpio' imprinted fob in my hand as I'd travelled to London and I'd resolved that the keys should find their final home where I'd tossed Dad's set at the beginning of the year. So, I found myself once again striding out along the path across Rainham Marsh, the bright afternoon sky having turned to a purple-grey churn of cloud with a wild wind thrashing at the stems of reed which lined the Common Watercourse - one of the many channels running into the Thames where it met the estuarial Ingrebourne. I stopped at the spot where I'd gazed across the marshes months ago, and summoned the resolve to slip the pair of keys off their ring. Without daring to hesitate I tossed them into the dark waters, breaking the bright green algae-covered surface. Slowly, the ring of clear water opened up by the keys began to diminish, the green carpet almost covering the surface again. I laughed a little at myself - this strange, sentimental ceremony at a spot which meant nothing to my family as such, but which had come to mean a great deal to me. A place where for centuries people have left the secrets they don't want rediscovered - but for me a place of remembrance. I looked out across the darkening marshes following the line of electricity pylons until it merged into the elevated route of the A13. There was an incomplete walk out there somewhere, but my business here was done. I turned and headed back towards the station, the wooden key fob held tight in my pocket. Back in February leaving the marshes had felt like an ending - when in fact it had been the start of a long year of goodbyes. It had taken me a long time to feel ready to even start saying them.

You can see a gallery of images from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.