It's a long time since I've made this trip...

As we skirt the edge of the Hamble Estuary in bright, spring sunshine I can almost ignore the weird doubling-over sensation in my gut. We've spent a few days in Brighton - a long promised destination, and one which has figured fairly often in my previous travels. That's because for a while, in the early part of the last decade, there were proper trains heading that way each Friday. I'd escape from work early, dash up to Bristol and hop about the four tired old carriages for a long afternoon's slog along the South Coast. Then, after some swift shopping in Brighton, I'd head right back. I even remember the time everything went badly wrong at Southwick and despite our driver's valiant attempts to coax the engine to Brighton, we blocked the busy route along the coast for some time. There were taxis, mad dashes to Mr Dong's takeaway in Cosham, and ultimately the satisfaction of getting out of a bind. Brighton is somewhere I've dashed into, around and out of swiftly. I'd never stayed in Brighton until this week.

Our hotel - really a some what glammed-up guest house on New Steine, just off the promenade, was comfortable and despite some oddities was entirely redeemed by serving a killer breakfast. We were a short walk through interesting, confusing Kemp Town from the Pavilion - and we took advantage of this to finally visit this bizarre example of Regency bling. The building was beautiful down to the surprisingly well-equipped kitchens which were light, airy and clad in clean white tile. The music room, victim of a mindless arson attack and storm damage over the years, was truly awe-inspiring. A high-vaulted, wonderfully colourful soaring place of wonderful decorations and surprisingly well thought out acoustics. Beyond the Pavilion were the Laines - numerous streets mixing genuinely innovative small businesses with the kind of 'alternative' shop which crops up in such spots. The wonderful Resident Records and several fine book and craft stores rubbed shoulders with junkshops rebranded as vintage emporia, vegan cafés and speculative tourist traps. The atmosphere though was rather special - like the Freemont Streetmarket in Seattle had landed on a warm spring afternoon in Sussex.

One of the goals on this trip was to experience The Salt Room, a recently opened restaurant on the sea front which garnered a wonderful review from Jay Rayner a month or so back. We weren't disappointed, and wandering along a breezy, dark prom after a fantastic meal which rather unusually felt like it had been worth every penny, we were both happy and pleasantly full of good things. Our other eating experiences here were less fantastic - with one local Spanish eatery which I won't name very likely giving me the dose of stomach cramp and nausea which seized me so inconveniently this morning before we headed back. Suffice to say, the owner and I are going to have words...

But after a long weekend in London, then heading for the coast to take early seaside walks, drink good coffee in the amazing Twin Pines, and to relax after some taxing times - well, it's been a good break which even some minor accommodation issues and a dodgy tummy can't ruin. Brighton was the unmistakable mixture which makes up the British Seaside - slightly down-at-heel and peeling, but surprisingly resilient to change. The city has embraced it's alternative reputation, and feels genuinely inclusive and welcoming despite being somewhere our grandparents would recognise readily.

There are a few more pictures from the visit here.

I've written before about my early interest in roads - one that has never really gone away, and has often reawakened at times I've felt challenged or frustrated. That I now have a willing partner in crime who is happy to take sometimes quite lengthy excursions has meant that I've finally had the experience of driving on some of the roads I've mythologised over the decades. However, some roads are meant to be walked - roads which have existed in some form for hundreds if not thousands of years, which despite the layers of surface dressing, hide the oldest of byways beneath. Occasionally my explorations coincide with these roads and I find myself needing to walk out the obsession all over again. Today was a bonus - we were in London on route elsewhere, and I had an entirely free day in hand. While I'd immensely enjoyed the guided walk I'd taken last weekend, I wanted freedom to cover ground at my own pace. I was also disinclined to head back into the wilds for this - an excursion without mud felt like a good idea. I wanted feet tired from walking, not aching from slurping through the liquid surface of the Essex edgelands for a change. This all coalesced via a chance reading about the A503. I'd crossed Forest Road near Waterworks Corner back in February and had been mildly curious about its route. While useful and strategically important, this east-west cross route in the north of London is fairly insignificant in the scheme of things. In the west Seven Sisters Road is a product of the eighteenth century expansion of London and a former turnpike. To the east, Ferry Lane and Forest Road describe the route of the more ancient Clay Lane from Walthamstow to Epping Forest. Along this route, the humble A503 crosses the routes of many of my previous walks - the Regents Canal, Green Lanes, the festival of gentrification at Woodberry Down near the New River, the Lea Valley. It ends just shy of the North Circular - the ever present connection that writhes through this terrain. In short, the A503 was the perfect long slog for an unexpected walk - a chance to make new connections and revisit old ones.

The bus deposited me on Camden High Street, a little north of Mornington Crescent. This isn't my favourite part of the world for a host of reasons, but mostly because in its slightly battered drag of chain outlets and copycat markets, Camden feels like what happens after gentrification. When I was a youngster, Camden was aspirational. The stars of British indie-pop propped up its bars, the record stores and vintage clothing outlets were legendary, the market was a wonder of new and old things which seemed exotic and impossible to us. It had developed this reputation slowly and surely through the 1970s, as the railway retreated and left large areas of land and old buildings free for exploitation. The real estate felt shaky and ill-kept, but that didn't matter to a post-squatter generation who liked their urban landscape to be edging into decrepitude. By the late 1990s, Camden was a different place. The huge footfall around the market and the High Street made the area attractive for the larger chains - and even though some of them were careful to invest their usually identikit outlets with a little uncharacteristic local personality, they were pricing out the smaller traders. Aside from the official market, every bit of clear land was taken up with semi-permanent stalls selling mobile phone cases, Bob Marley decorated stash tins, the usual stuff which could be found on the fringes of any shopping area. Each Saturday saw an influx of tourists eager to walk the High Street in order to pick up some of the perceived kudos of being seen around here, and the streets were full of expectant young faces from the provinces who - despite being in Camden - wanted the reassuring taste of McDonalds or KFC. First of all my route took a wide loop around this zone to find what might be the beginning of the A503 - heading counterintuitively west along Delancey Street and turning east again when I reached the bridge over the lines leading out of Euston Station. I'd strayed along this way in search of the bridge over a deleted arm of the canal, and knew the area a little. At Britannia Junction, the complex meeting of ways at the heart of Camden, I paused for coffee. I'd started earlier than usual today and needed the sustenance if I was going to make the distance. Looking out on what may or may not already be the road I was going to walk, I noted a gradual change. As the locals had headed for work or dissipated back into their homes, the steady stream of passers by appeared to gradually be shifting towards tourism. It was time to leave Camden.

I was briefly disorientated on crossing the street - Britannia Junction was a complex and many-armed beast. But the route I was taking almost immediately passed a familiar location - the same Sainsbury's I'd ended up detouring to find on my canal walk. I'd taken such a long circuit to get there last time that I'd lost the sense of just how close to the Canal I was for much of my Camden tribulations. This time I passed by, beginning to fit the area into shape in my mind - at least I'd have an escape route should I find myself here in future. As I slowly slipped out of the gravity of Camden the route began to change. Passing under the railway bridge at Camden Road station, beside its rusting and disused twin, I found myself climbing steadily on a broad suburban route. The stores thinned out into local hardware shops, convenience stores and petrol stations. The morning had started out grey but was clearing, and I was suddenly aware that the novelty of wearing a coat - something I've always studiously avoided until this winter when I finally found a comfortable and sensible garment for walking - was wearing off. I was far too warm. Getting an earlier than usual start on the walk and knowing I had accommodation in London overnight meant I could take a slightly slower pace than usual. No bad thing - this was quite a long route on pavement, with none of the diversion into the wilds I'd encountered recently on these walks. Despite having the time to divert and investigate things off route, I decided that wherever possible I'd stay true to the mission and indeed I largely stuck to the route I'd hastily planned. Above me the road was clearly marked: A503 Holloway, striking out north and east. Looking south when gaps in the row of tidy houses and small businesses permitted there were glimpses of the distant city as the road rose gently. Crossing the railway from St. Pancras on its broad westward curve towards Kentish Town, I sensed the change. I'd left the orbit of Camden, broken free and entered the uncertain northern hinterland which I'd spent so much time exploring in recent months. This part of North London doesn't quite cohere for me - districts blur and shift, and aside from the definite points marked by road junctions, the estate agents are drawing the maps here. The road stretched long and straight, reaching a peak from where I could see ahead to a fork. Where the road divided around a former garage with a gloriously modernist swooping roof, I took the left-hand path heading along Seven Sisters Road. Here, the A503 is a long one-way system enveloping Holloway completely in its two arms. Blank red-brick walls defined the perimeter of the former Holloway Prison. Empty and slowly returning to nature, the entrance was beginning to show signs of decay. It's just a matter of time before the sizeable site is snapped up and renamed to disguise its heritage. The area has a pedigree for residential land-grabs too - beyond the prison was a pleasant run of public housing owned by the City of London Corporation, one of the ten estates situated outside the square mile which it runs. Clean and tidy, the homes appear apparently well cared for and popular. I was prepared to find this part of the walk dull and mildly threatening but nothing could have been further from the truth. It is fair to say that Holloway is somewhere in the middle of a gentrification journey. Significant parts of the fringes of the area seem to be doing well, housing locals and providing decent services, while others seem to be undergoing that last, sorry stage of deliberate decay while their owners wait on the market and the right kind of investment into the area. At Nag's Head - where Seven Sisters Road meets Holloway Road - the scene is more disputed. As I lingered waiting for the confusing temporary lights on the crossing of the A1, I surveyed the area - it could be the centre of any London suburb, maybe even any small town perhaps. But among the well-known names and high street staples were a good number of tiny, local traders soldiering on behind long outmoded shopfronts. Beyond the stores to the north of the street was the muscular back elevation of the Beaux Arts Building on Manor Gardens. The front is a swirl of detail in brick, a grand Edwardian entrance to newly refurbished apartments - but the rear is stark, white and impressive. A single red brick chimney rises among the wings, which from above describe a trident pointing directly at the heart of London.

At Finsbury Park Station, the two arms of the road swing back together where the dome of the North London Central Mosque gleams over the three bridges carrying the railway north from Kings Cross. This mosque is something of a symbol of the triumph of peaceful Islam over extremism, with the Muslim Council of Great Britain seizing and reopening the site after a raid in 2003 which finally ousted the remains of the regime of Abu Hamza al-Masri. This splinter sect had been operating a programme of radicalisation from the building, some straggling tentacles of which reach forward into present-day terrorist activity. Emerging from the bridges, the transport interchange is a confusion of activity, with buses lurching around the tight curves outside the station. An unbroken stream of people are leaving the station with some Arsenal shirts already in evidence in advance of their FA Cup tie later in the afternoon. The sun had climbed above the buildings and I was starting to feel much too hot, but the road was curiously mesmerising - taking an almost straight course from district to district, through changing scenes which are both unfamiliar but entirely expected in their nature. North London is slowly starting to fit together in my mind, and the passing junctions connect me back to earlier excursons: the end of Stroud Green Road links me back to walking the Northern Heights. Everything finds its place here. Soon after passing the station the road quietened, and for a while it was just me and a constant stream of buses edging along the green fringe of the park. I'd walked this stretch before - between the treelined slopes and the long range of stucco-fronted hotels and large Victorian villas. It was pleasant to be out of the urban area for a while and to reorient myself by way of local landmarks: the towers of the Castle Climbing Centre and the forest of cranes at Woodberry Down. At Manor Park, I crossed Green Lanes and entered Hackney, completing my navigation of all arms of this important crossroads where the ancient road to the north crossed the relatively new turnpike. The organic cafe on the corner was busy - a signifier of how this area is changing, and indeed how quickly. The buses which have been shadowing me peel away north towards Wood Green and my route, now a broad dual-carriageway arterial, slips between the tall municipal blocks of Woodberry Down. On my left, some of the original blocks remain with their curved red-brick balconies - but as residents leave for the last time their doors and windows are securely plated over, the buildings slowly giving way to their regeneration. There's no rush to move them out - all the activity is to the south where the range of residential towers extends further eastward along the banks of the New River and the pair of broad, glassy reservoirs every time I visit. The desirable waterfront properties are for sale, not for rent, and definitely outprice the locals who are being slowly decanted from the ageing low-rise brick blocks. I popped into the local store and improvised lunch on the banks of the reservoir watching young couples leading curious children along the river path while ducks and gulls pecked around for crumbs. It was good to sit and cool off near the water and interesting to see how this area had changed since my earlier visits. The older population who had pottered the previous sandy incarnation of this pathway wasn't in evidence at all now, and there was a surprisingly homogenous feel. While the new buildings are undeniably a better environment in many ways, they don't appear to be fostering the sense of community which originally drove the aspirations of this early attempt at changing conditions for working people on a massive scale. Aware I still had some way to go, I set off to regain my route as it began a turn to the north at a crossing of the broad loop of the New River. Looking back along the inviting but still rather muddy river path, I had a view across the serrated rooftops of the somewhat directly named Harringey Warehouse District which sits at a distinctly lower elevation than the bank carrying the waterway. The A503 provides a boundary to Stamford Hill here, climbing respectably away from the factories and warehouses to the east with pleasant avenues leading away into Hackney. The walking was pleasant - perhaps a little cooler here, thankfully - and I relaxed into the rhythm of the traffic which was less intense along this stretch. The calm ended abruptly at the junction with St. Ann's Road which sat directly under the Gospel Oak to Barking railway line, the overbridge hemming the traffic into a complex junction and bottlenecking pedestrians into crossings which took an age to activate. Under the bridge it feels gloomy, damp and a little unsettling - perhaps reflecting the next part of the route? Looking ahead the road stretched onward between dilapidated and tired low rise housing and ranks of surprisingly attractive but mainly abandoned brick warehouses. Seven Sisters Road ghosts the missing edge of an incomplete diamond of railways here, the broad green areas of wasteland at its centre tantalisingly crossed by unofficial paths - but they're for a day when the ground is drier perhaps. A further railway bridge completes the diamond, and I'm in Tottenham - the change is imperceptible at first, but as I approach the A10 at Seven Sisters, the switch is suddenly closed. The tide of people waiting to cross the High Road couldn't be more multiculturally representative if an over-eager HR Officer had lined it up for a photograph. The junction throbs with life, a fog of traffic fumes undercut by the smell of barbecued meat and strong aftershave. Cars stopped at the light shudder with low-end from their speakers. Once, a ring of seven elm trees graced Pages Green - the original Seven Sisters - now a small linear park leads away east between the superstore and the terraced streets. The High Road is a stream of buses stretching north towards White Hart Lane and the tower blocks of Edmonton Green in the middle distance. For a little stretch I need to walk this route which absorbs the A503 briefly, marking a boundary between its distinct sections: the venerable turnpike and the ancient road across the Lea Valley.

Tottenham High Cross is an ancient marker on the route of Roman Ermine Street, often confused for an Eleanor Cross but somewhat plainer despite some added ornamentation in the early 19th century. Here I turn aside and head down into the valley, taking the appropriately named Monument Way. After a brief detour into a retail park at Tottenham Hale which feels oddly makeshift and provisional, I cross the vertical obstacles which separate North and East London - the Eastern Counties Railway, Pymmes Brook, Lea Navigation and the River Lea pass under the road in rapid succession. The valley bottoms out into a broad plain which has been flooded to form the chain of vast reservoirs which shadow the river here. After the Ferry Boat Inn, marooned on a spit of land between the Lea and the Coppermill Stream, the road joins a narrow causeway between these manmade lakes, with the railway curving in alongside. The gates of High Maynard Reservoir are locked to all except licensed fishermen - a regiment of heavy padlocks securing the gates, while wading birds strut the banks like guardsmen. Along the causeway unfinished electrification gantries from the recent railway works become a row of ominous monuments. In the distance I can see the land rising away from the valley floor, and I realise just how far I've got to go to reach my self-imposed destination. I'm distracted by designs etched into the pavement showing the transition: from industry and water to entertainment and nightlife. The progress from borough to borough is marked carefully - Waltham Forest wants us to forget the lines of pylons marching behind us and the broad swathe of churning green water. Ahead is art, culture, food and wellbeing. This once downtrodden borough is getting a very public makeover, its various urban centres being remodelled to promote promenading and restrict the motor car. Walthamstow is changing. I've seen the 'Awesomestow' banners - that clumsy appropriation fails on so many disturbing levels. I've also seen the row of achingly retro stores on the corner of Blackhorse Lane - the 'home of people who make and create' and I've seen the rebranding attempts as I've skirted the district, but today I'll be facing it squarely as I make a transit across Waltham Forest towards the east. I don't object to this area - in fact I rather like it - but I don't need to have this unsubtle exercise explained to me. Let us all discover - or rediscover - the borough. Don't force it, Walthamstow.

This is now Forest Road, and as it makes eastern progress away from the Lea Valley the stores return to type: small newsagents sponsored by Lebara and occasional hair salons. The pedestrian schemes are still incomplete out here, and the traffic remains dominant. Long ranks of tidy suburban avenues lead north and south and the road is fairly unremarkable aside from a fine modern Fire Station building. Rather suddenly, the carriageway kinks to the south to skirt the grounds of Lloyd Park House - now the William Morris Gallery. This sizeable but modest building sits at the corner of a broad green space beyond a walled garden, which is apparently well-used on decent afternoons like this. Formerly Water House this was the Morris family home from 1848 to 1856, while the adjoining Lloyd Park includes a moat which long predates the Georgian building. The space in front of the gallery offers a moment to rest and reconsider the walk - not least how I'll escape from the end of the road when I reach Waterworks Corner. I hadn't really planned for this - the road had seemed impossibly long, and the chance to walk without worrying too much about time had lulled me into not considering how I'd mark the completion of the walk. There was a way to go yet though, and as the road climbed towards The Bell and a house-sized mural of Morris glared across at me, I had a view of the distant green horizon where I was heading. My route skirted north of the central area of Walthamstow which clusters around busy Hoe Street, and remained resolutely suburban until I crested the rise and looked down on the pale verdigris of the clock tower topping Walthamstow Town Hall. As I approached, the full extent of this impressive civic complex unveiled itself: first a broad, low magistrates court building now closed and sold to the Borough Council as part of the Ministry of Justice estates rationalisation. This patently 1970s creation of the GLC Special Works Department can't truly be considered a brutalist structure, as it relies on Portland Stone to offer its simple but muscular face to the world. Beside it sits the more classical but no less imposing Town Hall by Philip Dalton Hepworth - a broad, mausoleum-like sweep of stone completed against all the odds in 1941. Its geometry aligned with a central fountain and a processional route to the doors, and I found myself precariously perched between the gates while trying to snap a picture. A citizenship ceremony was being completed as I approached, with impeccably dressed celebrants leaving the campus to the disgust of a couple of locals who leaned on railings, spitting and moaning about them "not being really British". As they'd inadvertently roped me into their conversation I pointed out that that was now exactly what they were. More spitting, more moaning about this 'fuckin' lefty'. Finally, the broad colonnade of the Assembly Hall completed the site and Forest Road began to climb again, passing the extensive Waltham Forest College buildings. This area is rigorously zoned, these public buildings dominating the east-west road as it cuts across the ridge between the Lea and the Roding. Nearby, a grandmother passed me, stooping to encourage a young girl and reassuring her in a surprisingly breaking voice that they'll do something "when mummy gets out". Initially I'm confused by the significance - but I soon spot Thorpe Coombe Hospital, a Georgian house turned into a Health Trust building with a residential psychiatric unit on site. I find myself sharing the young girl's pain and confusion, the sense of separation and the power of places to divide and distance. I'm surprised how this part of Walthamstow has passed me by before - the odd gravity of this administrative complex which powers the district like a civic engine room, dealing with its difficulties and tidying away the awkward and ill-fitting. I felt strangely ill at ease as the road turned uphill again, the horizon lost behind the ridge and the rising streets of Walthamstow behind me, if I'd dared to look back.

As I climbed, somewhat unexpectedly the deck of a footbridge appeared above the road - and as I slogged further up the rising path, the steep grassy banks supporting it emerged and I realised with some surprise that I was almost at my goal. The flat grassy deck above the sunken reservoirs opened out, and I could see the spot where I scrambled thankfully down from the forest path on my last walk here. Ahead of me the A503 ended at an unusual urban cattle grid near a junction with Woodford New Road, just shy of Waterworks Corner roundabout. I had mixed feelings as I approached the end of my walk - firstly, that I should perhaps press on further east, following the North Circular? The transition I'd made from the fading glamour of distant Camden to the leafy suburban spaces of Woodford felt jarringly odd and unresolved. As I circuited the roundabout to find a path across to the northern side of the shuddering and screaming A406, I noted the forest paths were still awash with thick mud and deep ruts. The subways under the roundabout were little more than continuations of the forest trail with strict instructions for horseriders to dismount. Beneath me, huge eastern European juggernauts paused in the lay-bys, the soles of their drivers' feet propped at the windows as they sleep until they're permitted to drive on. The traffic noise reverberated through the tunnels as I negotiated a route out onto Grove Road which edged along the deep concrete gouge which channels the road. The sun was beating down now, and there was a remarkably long view into the eastern distance. As the land fell away into the Roding Valley I had a clear vista of rooftops and distant woodland, and rather shockingly protruding from within the woods I saw the tower of Claybury Hospital winking into the spring sunshine. For a while I sat in the strange little makeshift seating area on the edge of Woodford where the North Circular cannons underneath the urban centre. A steady procession of happy young faces trotted into town, buses shuttled back and forth. It felt strangely peaceful - like the road echoing below my seat wasn't really there. I shuffled creakily into South Woodford to find a bus stop, conisdering that it could be any town centre in the home counties. Over my shoulder the tower signalled from my previous walks, shimmering over the ranks of heavily mortgaged Essex real estate. I was back in comfortable territory on the edge of things, but not everyone here was comfortable or secure. I thought of the girl and her grandma shuffling west from the civic centre of Walthamstow and of the sorrowful history of Claybury and its sister asylums, and I felt very grateful I was heading back to my own tiny family.

A gallery of pictures from the walk can be found here.

I've always been a little nervous about guided walks. From the awkward, rather typically British issue of trying to identify your fellow walkers at the outset - ideally without actually asking anyone - to the tricky etiquette of dispersing at the walk's end, they're a minefield. I once thought I'd like to lead walks - the idea of ambling around places I love with a respectful and engaged bunch of people both asking questions and adding their knowledge was attractive, if unlikely. Of course the reality is often different: bored tourists "doing" the sights, loudmouthed know-alls trying to upstage the guide, people with no spatial awareness causing minor traffic incidents. Guiding walks wasn't for me. In my attempts I also realised a simple truth: firstly most people just aren't as interested in the minutiae as I am. I've often thought I was boring or lacked the capacity to engage people - but as I've grown older I realise I'm just engaged differently. I've learned to live with this, and find myself surrounded by people who are at best encouraging, but at the very least tolerant of this. So today I approached a group of unlikely looking people assembling near Tower Hill station with some trepidation. We were going on a walk together - which for someone who jealously guards his excursion time, was a remarkably intimate association with strangers.

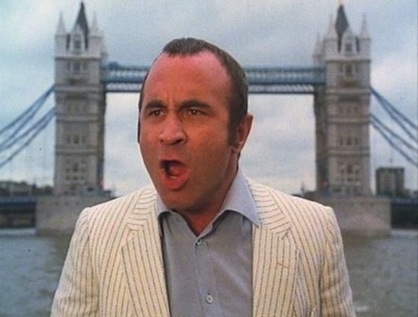

Today's trip focused on locations from The Long Good Friday - the 1980 movie which launched Bob Hoskins on his path towards being the nation's 'loveable villain' figure in Harold Shand, and which almost didn't see the light of day due to the inclusion of the then horribly ever-present IRA as the bad guys. Or perhaps more accurately as the worst of the bad guys - there are no good guys in the film. In some ways, despite the brash edge-of-the-eighties optimism, the glamorous yachts and the presence of some weirdly prescient tropes which would haunt London for decades to come, the movie has no redemptive ending. My first viewing of the movie years back left a couple of impressions - that London was unrecognisable for the most part, and that it kickstarted a good number of British acting careers. John Mackenzie's clear vision that this should not be the London of red buses and black cabs had wrong-footed me. But as I've walked the hinterlands of the city over the years, I've come to recognise Harold Shand's London - sometimes it is buried, sometimes it lurks in the most unedifying areas, often it requires a mixture of research and imagination to conjure it from the anodyne glass and steel of the modern city. But it lurks not far from the surface, buried under the very Thatcherite dream which Hoskins invokes as his yacht passes under Tower Bridge at the beginning of the movie. The regeneration of the docks, the opportunities for investment, London positioned as a European capital - calling the shots, not taking the bullets. Those predictions which must have seemed so outlandish to anyone who knew the dereliction of the Isle of Dogs and Royal Docks in the 1970s, now elicit a gasp of recognition followed by an ironic guffaw: the European dream is close to being over, the '1988 Olympics' which Shand proposes happened - if a little later than scheduled.

Our guide was the placid, knowledgeable and powerfully-voiced Rob, who called the group to order and set out the plan. We'd walk for a couple of hours, visit a number of locations used in the film and chart the progress of Harold's dream towards the Docklands of today. He'd play us contextual clips of the movie on his iPad - so we could gauge just how much had changed and how much remained of Harold's manor. I surveyed my companions - there were of course stereotypes: the older guy who sticks to the guide like a minder and engages all of his time between stops in discussion, the gent with the expensive camera who wanders all over the place taking endless shots of everything but the subject at hand, the middle-class intellectual couple who roll their watery eyes at each other when the discussion has to be simplified or edited for the sake of time or sustaining group interest. We shuffled off, over the messy tangle of crossings outside the Tower of London, over the neck of Tower Bridge where Police were zooming to some sort of incident involving a group of yelling tourists, and towards the Thames near the huge concrete hotel. This was the first point at which imagination would be challenged: we were asked to picture warehouses - full of spice and indigo, a river teeming with ships waiting to unload. Some had waited weeks, some even longer. The Pool of London was jammed and dangerous - haunted by river pirates who took advantage of the vessels stuck here waiting to be unloaded - some in the most violent of ways. London needed new docks and new suburbs to support them - and so St. Katharine's Dock was constructed. By the time Harold Shand was mooring his luxury yacht here, the dock was deserted and in disrepair. Several of the large, impressive warehouses had already fallen to new development and only the Ivory House remained fully intact. Today the view was surprisingly similar if the skyline beyond the warehouses was discounted, along with the modern housing which had sprung into being on three sides of the basin. In the corner the Dickens Inn tumbled towards the docks, its provenance not entirely honest - being some form of reconstruction from recovered materials on a new site. The marina was busy with boats which would have rivalled Harold's for style and opulence. It was clear from the outset that this walk was going to deal in contrasts.

We progressed towards Wapping via the river front, recalling the shot where Hoskins was framed by Tower Bridge as he gave his rousing, patriotic call to 'the right people'. It quickly became apparent that this walk was unwinding two narratives - the fictional world in which the movie played out, and the uncannily similar events which followed just a few years later via the London Docklands Development Corporation. Shand's own 'corporation' fell prey to retaliatory attacks by the IRA and we saw the corner opposite Scandrett Street where, by virtue of a limited budget, a plywood East End boozer had been constructed to be blown up. We stood below, picturing the sight from the ground, where Shand's car had been seen arriving from the narrow street beside the then abandoned school buildings. Just a short walk around the corner we found the squat, yellow brick St. Patrick's Catholic Church. Apologetic and a little featureless outside, the interior was elegant and lofty, with brightly decorated iconography and dramatic columns climbing to a surprisingly lofty ceiling. Outside we strained to see St. George in the East over the rooftops, as the scene where Shand's mother narrowly escapes a car bomb was a composite with Hawksmoor's striking edifice playing the exterior while St. Patrick provides a fittingly non-Anglican interior. We didn't head for St. George this time - but I'd spent enough time stalking the environs to be able to picture the switch perfectly. Around the next corner we found Dundee Street, with warehouses now converted into flats and offices. Above the street, bridges crossed between windows completing the image of gentrified dockland living. It was here however that a young Gillian Taylforth played the young women who discovers a dying security guard nailed to the beams of the floor in a perverse play on the film's title. The religious imagery is deftly done - temptation, betrayal and sacrifice played out in the slightly distended timeline of a single day.

Approaching the Limehouse Link Tunnel, the story shifted from the plans which Harold Shand had for a new city, to the events which took place here in the 1970s - Michael Heseltine's helicopter flying low over the abandoned wasteland on a return from an abortive excursion to Maplin Sands. His development of the LDDC with the plan to free the area from the shackles of council inertia and the too-and-fro of the same old guard in Parliament. He gives them comprehensive planning powers and just enough money to buy land and sell it cheap. At the same time, London Transport scoff at serving the area with any sort of serious service, and instead the Docklands Light Railway springs up - a budget train-set to fit the low-rise developments which are springing up. Heseltine wants to see people living and working here again, but it's slow - painfully so - and far too glacial for Nicholas Ridley who follows him into the Environment brief. He has a new vision: leveraging private capital to spark life into the Isle of Dogs. The Canadians arrive but want the infrastructure before they commit. Soon the DLR is expanded, the Limehouse Link digging begins - possibly the most expensive road project ever in the UK at that point. Slowly the towers climb from the water. But - abruptly - the market crashes and everything stops. The abundance of empty office space across the major cities of the UK and Europe makes a folly out of One Canada Square, the tower which glowers over the island with a baleful pyramid and an ever present smear of smoke at its apex. It may as well have been burning money.

Then the IRA make their own leap from fiction to fact - this time in a genuine and devastating way. On 9th February 1996 the two-year long ceasefire ended with a huge explosion under the DLR on Marsh Wall. Two men, local newsagents, were killed in the blast which left a huge crater in the ground and destroyed one building, and damaged two others seriously. I remember a DLR trip through the area some weeks after the bombing - the shell of the Midland Bank building with its empty windows and flapping blinds standing eerily beside the track as we swerved and dodged around the tight curves between docks and offices. This and a range of other IRA actions in the City of London and Manchester achieved what no amount of government money had managed - it created a market for decent office space. The development of Docklands was perversely rejuvenated and soon Canary Wharf was at the very heart of the plan. Soaring from the mirror-like surface of the former docks, new office towers grew swiftly with the emblems of international banks blinking into life above them. As we arrived at Canary Wharf it was nearly impossible to imagine this was the site of Harold's betrayal in the movie. His blood-soaked stagger from the yacht with a Lear-like howl towards a focused, cool Helen Mirren took place at a point before any of this could be imagined. The deserted dockside with its rank of low sheds along their edge didn't promise this kind of future, and at this point in the movie with his betrayal complete his scheme to bring prosperity seems unlikely to succeed. Now, the impressive brick sheds are the only surviving reference point - housing the Museum of London in Docklands, they are busy with visitors. Across the dock, the glassy torpedo of the new Crossrail Place appears to be moored alongside the office towers, the uncommissioned platforms sitting far beneath the water. The walk ends here, the story complete and Harold Shand's dream delivered despite his almost certain fate at the hands of a young Pierce Brosnan. Using the movie as a lens through which to view the change wrought on this part of the Isle of Dogs was a surprisingly clever ruse, and I can't help but feel that our rather oddly matched group of walkers would never have been assembled for a straightforward 'Docklands history walk'. They might have sniggered and sighed at the names of Conservative politicians of the 90s, but in doing so they missed a point - the plan in its original form was to remake part of London very much in its own, older image. What happened here, what has grown as a strange, disembodied and distinctly transatlantic city beside the city, is as much the result of subsequent governments of both parties' losing grip on the financial sector.

Suddenly, I was alone in the midst of the new city. The group dispersed, even the guide's most ardent hangers on finally leaving him to head for the station. The small square, tucked in beside the replica of the West India Dock Gateway with its elaborate model ship, was windswept and empty. Construction on both sides of the square meant no-one much was heading this way. I tried to decide what to do for the best. The guided walk had taken a little longer than I expected and I'd not thought through my options for the afternoon. I decided to grab a bite to eat before trying to complete a stretch of walking I'd meant to cover for some time - the perimeter of the Isle of Dogs. First I had to negotiate the mall which sits under One Canada Square. I'd been here before, many years ago, and I knew there was a small supermarket near the DLR station. Getting there was a challenge - I'd never arrived at ground level before, and even the concept of 'ground' was less than fixed here. I found a lift and ascended from the sub-zero floors towards the surface, which was in fact the level of the bridge carrying people across to the soon-to-be Crossrail station, finally finding myself at the store near the DLR which was, today at least, closed for engineering works. Purchases made, I retraced my steps out into the broad square and perched beside a cool fountain to eat and plan a little. It didn't take long for a uniformed 'Canary Wharf Estates' employee to take an interest. After wandering around the general area for a little while he plucked up the courage to come nearer. "Going to be long?" he enquired? I took a silent slug of water and said "Not much longer, just having a breather before I walk a bit more". He looked like he wanted to ask more questions - but he was young, inexperienced and a little unsure. I suspect he'd have found it easier if I was a rolling drunk or an itinerant begger - someone he could legitimately move on using the powers he had on the private estate. Instead I was a reasonably polite, reasonably tidy chap who had happily answered his question. "Well, take care then - and no hanging about" he managed before he scuttled back towards the building. I dusted myself down a little, took some defiant shots of the building towering above me, and headed along the edge of Crossrail Place. At the end of the walkway where the building petered out and the dock resumed, things were a little ragged. There are still rough edges to the Canary Wharf estate, and if one walks to the perimeter they soon become apparent. Turning alongside Bellmouth Passage I climbed stairs and crossed a street near empty offices, finally escaping the estate via Trafalgar Way. The staffed sentry post was active, the private police force beckoning cars forward to have credentials checked while flagging buses into the site. I looked across the broad empty area surrounding Billingsgate Fish Market, and across to Balfron Tower and the towers of Stratford beyond. It was a surprisingly sunny afternoon, though you'd never know it inside the estate, where the buildings reflect only each other.

I found myself not far from an area I'd walked some while ago, near Poplar Dock Marina. Ahead was the route to Blackwall and Leamouth, but I turned south cutting through a carpark to regain the A1206 as it started a long curve around the island. It soon became apparent that trying to use the river path was going to be a fruitless and time-consuming endeavour. The path was frequently broken by developments, sending me scurrying back and forth to find a route south. Instead, once over the impressive Blue Bridge I stuck largely to the main roads, with a brief excursion into the Samuda Estate. This rather forlorn range of London County Council blocks from 1965 looked tired and careworn, and at their centre stood the stark and impressive Kelson House. This twenty-five storey tower, made up of neatly interlocking three-level maisonettes, was modelled on Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation, with access via a separate slender tower on its western side. It wasn't as graceful or bold as Goldfinger's similar efforts, and was altogether more workmanlike and British in appearance - a building which could grace any city centre perhaps? That it survives is testament to a tenacious island population who have, on the whole accepted incomers and immigrants rather like any dockside community. However, in the 1990s the area had a period of more chequered history, electing the first ever British National Party councillor in Derek Beackon. Beackon appeared to be as surprised as anyone to find himself on Tower Hamlets Council, and struggled to manage the complexity or scale of work expected of him. Perhaps not surprising as his prior role in the party had been as 'Chief Steward' - effectively the organiser of the team of Skinhead bodyguards who circled the leadership in public. Beackon's 'rights for whites' agenda was perhaps surprisingly aided by the local Liberal Democrats who published their own literature complaining that the predominantly Bangladeshi group rehoused from Limehouse when the Link Tunnel was built were given priority in 'luxury' accommodation. With Labour and the Lib Dems locked in an idealogical struggle during the 1993 election, Beackon crept in by a margin of only seven votes and immediately failed to comprehend what was possible at the local level. His colleague councillors walked out in protest at sharing the chamber with an immoderate and loud-mouthed fascist. When the seat was again contested in 1994, Beackon was ousted by a concerted campaign by Labour, and while the white working class roots of the island persist, there is at least a sense of a shared community in this oddly isolated zone again.

Pressed for time, I began to consider my options. The plan to circuit the island back to Limehouse was possible, but I found myself rushing ahead and not taking in my surroudings. A steady procession of buses beside me on Manchester Road had been reassuring at first - a potential quick way out if time got tight - but now they felt like a nagging pressure. At Island Gardens I decided to rethink my plan. With the DLR out of action the square outside the realigned route was busy with people teeming from the Rail Replacement Services. Beside the shiny, winged modern station the brick viaduct which had originally carried the rails here was still standing. I recalled previous visits, long before the railway burrowed under the river, bailing out here at the end of the line and regarding Greenwich across the river from a bench in the small park. Seized by a sudden desire to relive this experience, I headed into the gardens and found my way to the river wall. The Thames buzzed with life - river buses and motor launches scudding over the brown waters. The Greenwich foot tunnel's domed entrances flanked the park, emerging beside the impressive bulk of the Royal Naval College across the river. Beyond, green space stretched away up towards the observatory. I lingered for a moment, before heading back to complete my loop around the island by bus. There was unfinished business on the island - and much to be explored within the deep loop of river - but for now at least, it was time to head back to the mainland.

It felt good to be on the move again. Despite my committed trainspotter status, I've begun to relax into our road trips and to appreciate the opportunity to see familiar places from a new angle. This time was a little special, and I was childishly excited to be setting off having spent a night in the curious hotel I'd walked by just last month. Our night on the fringe of Essex was surprisingly quiet and relaxing - waking to a misty view over Epping Forest and taking an early train journey into the yawning and stretching city, the fog slowly lifting to reveal a weak, wintery sunshine. We'd set off early and grabbed a coffee in the rather quaint surroundings of Buckhurst Hill - a little village centre in the midst of the suburbs. People came and went, their Sunday morning ritual observed. We lingered before setting off along the High Road and intersecting with another of my recent walking routes. It felt strange to be driving the route I'd walked, joining the North Circular at Waterworks Corner near the spot where my route had come to a slithering, muddy halt just short weeks ago. On a Sunday morning the A406 was still a river of traffic, but it flowed steadily and easily. I'd crossed and recrossed the route so often in this quadrant that unlikely landmarks suggested themselves: footbridges, sliproads and underpasses that had figured in my wanderings were oddly familiar - but striking seen from another angle. The road curved south, dropping into the Roding Valley and stalking the line of electricity pylons which had shadowed my walk through Ilford into an unexpected monsoon. The flyover buckled over the road into town, striding ahead on stilts to meet the A13 at Barking Creek while Tate and Lyle's works at Silvertown glinted in a patch of distant sunlight. As we cruised down the ramp onto this road of which I'd made a particular study and had walked beside for miles, the dust and accumulated detritus whipped against the railings: "there's so much trash!". The A13 was a rollercoaster to the sea - bridges leaping and twisting between the edges of industry and the broad marshes. Over the Roding, over the strangely makeshift construction at Lodge Avenue, turning south and east to amble over Rainham Marsh. Still so much drifting plastic rubbish, so much dust and burned earth. The aroma of the waste reclamation site hung heavy over the brooding marshland.

From some miles away we'd seen the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge arcing over the estuary, with speck-like vehicles hurrying over it's bowstrung deck. As we closed in, sliding effortlessly over the marshes which I'd walked with sore feet counting each step, the bridge felt unreal and fragile. Joining the lines of traffic climbing to its apex, all I could see ahead were the towers set against the pale estuarine skies. Beside us, the brown churn of the Thames was still and waveless. Lights winked from the tops of towering cranes at London Gateway, and to the west there was a smudge of silver-grey where the towers of Docklands stood. The nose of the car was down now, pointing at the green earth of Kent. We turned east again, the river visible here and there as Dartford slipped into Gravesend, before we disappeared into a chalk gorge with the High Speed railway line beside us. Suddenly we burst into an open vista of rolling, green woodland. The road marched ahead on a broad viaduct, with the sprawling Medway valley beneath us. There was surprisingly little trash to be found lining this route. South of the river is a different world, even out here it seems.

At Medway Services, a relic from the early 1960s which bridges the road offering a view back west as traffic crests the hill and zooms underneath M&S and Costa, we paused for coffee. We were nearing our destination for the remainder of our weekend, and needed to review the complex instructions for accessing the Canterbury Cathedral Lodge. The experience was pitched somewhere between a red carpet celebrity arrival and an East Berlin checkpoint: after navigating the ring road around the city walls, we entered an otherwise restricted road and turned a sharp right to a gated entrance. Our name was enough to lift the barrier. Permitted to enter only long enough to deposit our bags and collect a parking permit, we were soon to learn that rules and regulations were the engine of this place. Waking on our first morning I took my customary stroll. The sky was a dull pink-grey, the sun just beginning it's ascent. I gazed up at the butter-yellow stone of the Cathedral as I walked towards the gate, so impressively close to our lodgings. I was brought up sharply by a voice asking me to stop. The uniformed Catherdral Constables protected the precinct outside public hours with a grim determination: "How did you get in here?". I showed the pass card the hotel had issued - but that wasn't enough. ID was required - but I had none. Not being a driver, and not customarily carrying a passport in my home country, I wasn't able to support my pass with the correct credentials. "What are we going to do now?" the Constable asked sarcastically. My suggestion didn't help at all - "Find a real policeman?". Eventually they decided that a fistful of bank cards and suchlike bearing the same name would do, and let me out into the streets of the city. It felt oddly liberating to be among the tumbling old buildings and hidden alleyways of this ancient place. I headed for the River Stour and sat for a while in the quiet of Abbot's Mill Garden, the water cascading through a tangle of channels which once fed the wheels.

Despite the regime at the hotel which felt equally oppressive and challenging inside the building as out, we managed to relax and enjoy the city. Because of the atmosphere of a religious retreat inside, escaping the gates felt like an exhalation - and elsewhere in Canterbury we found friendly service, excellent food and very little of the bleak Protestant disapproval which the Lodge seemed to be founded on. Oddly, inside the Cathedral building too, the atmosphere was immediately different - charged with significance and history, the sheer burden of time crushed the fusty rules and deferred all to a higher authority. The vast nave stretched into the distance, rising to form Trinity Chapel where St. Thomas Becket's bones lay until disturbed by Henry VIII. He didn't prevail entirely here - this by far the most colourful, most Catholic of Anglican churches - right here at the heart of the diluted, English faith. Much of British history wound back to this place but it was far from an inert shrine for display purposes only: as we shuffled along the wall of remarkable monuments a funeral was beginning in the Quire. All too soon it was time to begin the trip home, but there was a further stop to make first. After a winding journey along country roads, tailgated by white vans and nearly side-swiped by throbbing BMWs, we turned a corner to witness the stark towers of the ruins at Reculver. I'd seen this uncanny, sublime view from the train window many times but close at hand, on it's clifftop roost, the scale of the proud, surviving towers was impressive. We walked the path to the towers, the flat field beside them covering the remains of a roman fortress. This spot had defended the coast for centuries - and the towers had served as a waymark for boats using the long disappeared Wantsum Channel and a navigation aid for the treacherous Thames estuary. Looking out across the water I could see distant ranks of wind turbines, and between them the eerily animate shadows of the Maunsell Forts at Shivering Sands. Beyond lay distant Essex, where this journey had started - and where I had further ground to cover, more business with this estuary. Lately, I'd been reading and thinking much about Charles Olson, and his words suddenly fell perfectly into step with the view across the water:

It is undone business I speak of, this morning, with the sea stretching out from my feetCharles Olson, Maximus To Himself, 1960

We headed back to the car to make the long drive west. Once again, Kent had surprised me with it's ability to ensnare me in it's history and to make me want to return. The haunting views at Reculver needed to be considered further, their stories unravelled in detail. We followed the taillights back towards London, and home.

There is a small gallery of pictures from the trip here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.