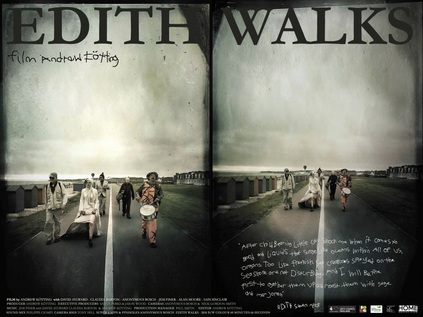

There is something rather special about one of Andrew Kötting's sometimes improbably odd film projects making it to completion, let alone a cinematic release. Getting to see one during its debut tour of British cinemas felt even more of a scoop - and I'd looked forward to this for some time. Coming at the end of a really quite troublesome and wearying week, and directly before I headed off on a summer holiday, it took on a further significance - it was, after all, a film about a journey. So we settled into the comfortable seats of Bristol's Watershed, realising that we made up a solid two-thirds of the audience. It was, almost, a private screening tonight.

Edith Walks has something in common with the majority of Andrew Kötting's previous long-form films - in that its sense of pilgrimage is almost all that holds its fragile elements together. This trek, just over 100 miles in total, attempts to create an as-the-crow-flies connection between Waltham Abbey - the last resting place of King Harold - and St. Leonards on Sea where his likeness is captured in a statue. In the sculpture, Edith Swan-Neck his handfast wife lifts the King's head tenderly from the battlefield at Hastings, recording both the moment he is discovered and that at which he is confirmed to be dead. At that moment, Harold slips from history into mythology - the story is written into every school history book, but the man slips wholly out of sight. The history goes that after Edith's discovery of the King on the field of defeat, he was segmented and parts sent to religious houses throughout the land. Finally his heart was taken to Waltham Abbey and buried. This walk, with six companions making up a clattering, chattering tribe to accompany Kötting and Claudia Barton as 'Edith', attempts to link Edith back to Harold - a reunification after 950 long years of separation - King and Queen reconnected, and man and myth made good.

The six companions are an interesting bunch in their own right - along with 'Edith', musician Jem Finer hauls a complex recording device that creates and receives sound as he walks - often the sounds provided by David Aylward, a percussionist who improvises his art marking time along the route. Pinhole photographer Anonymous Bosch captures events as they occur, while Iain Sinclair provides the closely-read mythological underpinnings for the story, sometimes bouncing his ideas against Alan Moore, the Seer of Northampton, who links deeper into the odd English Gothic. In Moore's telling, Harold never dies but becomes wholly subsumed into the myth - becoming Hereward the Wake, our first freedom fighter. Along the way, Barton sings - her remarkable torch songs providing a haunting voice for Edith which is entirely lost from the official account. As the companions progress along the Lea Valley, under the Thames at Greenwich and into Kent, their interactions with modern-day England form the narrative course of the movie. No-one quite knows what to make of them, and fewer still seem to fully understand their purpose. Such are the films that Andrew Kötting makes - miniature, absurd epics that mess endlessly with chronology, mythology and psychology in order to spin out a fable. If he has a message for the viewer it seems to be that you should believe nothing which you see, and even less of what you hear. Kötting's occasional background appearances, foolscap firmly pull onto his reassuringly solid, square head as he regards the antics of his companions are reassuring. There's someone else seeing this - it's not a dream after all.

Kötting's role in these films has always been a little unclear to me. Is he playing The Fool as a character - there to provide a foil to the incredibly erudite discussions that Iain Sinclair and Alan Moore share with 'Edith'? Or perhaps he's just there to orchestrate things - to deal with the unwelcome Police interest in Greenwich, or to corral the impossible troupe as it makes steady southbound progress? What he certainly seems to function as is a catalyst - it will be Kötting who decides to film a bow scraping at a bicycle spoke belonging to a bemused bypasser, or who instigates a conversation with Sinclair which delves into new theories and possibilities of the Harold/Hereward myth. The camera rolls, and there he is again in the background, grinning in encouragement. The architect of a particularly English sort of chaos. As Iain Sinclair has observed elsewhere, walking with others provokes story-telling and changes the dynamic of conversation. There's an almost Chaucerian element to the tales shared by the six as they progress south towards the provisional site of the battlefield, historical events represented by found footage of a 1966 school re-enactment of the battle.

The audience response to Andrew Kötting's films is often as varied, confounding and challenging as the work itself - and while I left the cinema amused and enlightened with a head full of reference points to review and research, my wife - a far more engaged cinema fan with a solid grounding in classic movies over the years - was genuinely enraged. She couldn't see a purpose beyond self-aggrandisement - but what sense was that if no-one was watching? We discussed the film and our various reactions for much of the journey home, and while her view softened somewhat she remained confused and irritated by Edith Walks and it's lack of narrative and deliberately obtuse and sometimes amateurish cinematography. For my part, I'm probably just as confused in many ways - but the playful oddness, the eccentric rewiring of history by way of a walk and the unwinding of a new mythology along the way absolutely appealed to me. Mark Kermode suggested in his own review of Edith Walks that as long as Andrew Kötting exists, all will be well for British filmmaking. It's a tough mantle to assume, and one I suspect Kötting might utterly refuse to bear - but I tend to agree that while he continues to act as documentarian and catalyst to these odd, location-specific pieces, there is much to be optimistic about after all.

London's Other Orbitals: The North Circular - Part 1

Posted in London on Saturday 1st July 2017 at 11:07pm

When I'm pressed to explain some of the walks I write about here, sometimes the best I can expect is a blank glance and a swift change of subject in response. The very worst is to be faced with is a single word: "Why?". I'm not sure quite when my simple interest in the topography of London became a strange drive to connect everything together. The sheer impossibility of knowing London is almost part of the fun: faced with the massive, overwhelming complexity of the city it is a perverse joy to find a corner where there is some unremarked detail ignored by almost everyone who passes just feet away. That said, I'm dreading the explanations for this excursion - a walk around the North Circular. On so many counts this doesn't stack up - after all Iain Sinclair walked the M25 years ago, unravelling the Thatcherite dream-highway as it wavered through the greenbelt. He found a road which symbolised a period in London's evolution, linking the ring of decommissioned Victorian lunatic asylums via a swathe of tarmac which was obsolete by design before its final opening. It was a manifesto commitment reluctantly delivered way over budget - like a band's final and pitiable album delivered to satisfy a contractual obligation. By comparison, the A406 is a more mundane entity, a road that gets the job done with very little fuss or esoteric bluster. A road that emerges from the old tracks and brooks of North London rather than being consciously designed. Its broad semi-circuit never quite breaks free of the post-war suburban sprawl of the city, yet for long stretches the road is entirely cut off from the communities which fringe the fume-filled gully which it occupies. Walking the North Circular was at best unnecessary and at worst seemed mildly unhealthy. But the curious history of this road has haunted my walks across the city: sometimes it has been a barrier to progress, sometimes a welcome shortcut between other tracks. Now it was time to pay my respects to this arc of tarmac properly - by walking it.

It feels counter-intuitive to head west. My general interest, my preferred territory and my familiar haunts are all in the other direction. I surface at Gunnersbury Station, now embedded in the base of a dull, glassy office block unimaginatively and innaccurately called Chiswick Tower. Across the street is the equally questionably monikered Chiswick Park - a diamond of late 1990s office developments by Richard Rogers which wear their slender white skeletons outside their mirror-glass skins. Nowhere, it seems, wants to admit that it's Gunnersbury. The grass is snooker-table short and primped, the site pristinely managed to the point of unreality. I venture in to find a tiny coffee shop situated in a free-standing oval pod, a single barista already sweltering in the metal box while she bustles through a large order for a group of Polish builders who effortlessly defy the 'No Smoking' signs across the footpath. While I wait for my drink I spot a small box sporting a bright yellow 'help' button. The sign is pitched just a little too hysterically for my liking: 'Lost? Confused? Need Help? Press here for Chiswick Park Estate Management'. As I sip my coffee in a designated seating area and make the final preparations for my long day of walking, I wonder just what kind of crises the employees and visitors to the companies inhabiting the park suffer regularly enough to warrant that kind of message? It is perhaps best not to guess - especially on a Saturday when the site is eerily and rather menacingly quiet. Instead I move on - back out onto Chiswick High Road, and just a short walk from the infamous Chiswick Roundabout.

If you've ever listened to an LBC traffic segment, you'll have heard this fairly ordinary traffic feature used as a barometer for the state of the Capital's roads. Here the M4 either starts or ends, depending on your viewpoint, while the older Great West Road - as immortalised by Chris Petit in Radio On is relegated to a supporting role, running underneath the motorway. This is also the only point where the North and South Circular roads meet, with the broadening estuary of the Thames breaking their imperfect circle where they attempt to reconvene out east at Woolwich. As I snapped a picture of the large sign on the approach to the junction, much to the amusement of some tourists checking out of the nearby hotel, I realised that at some point if I am to stay true to the rationale of my project, I'd need to suspend my prejudices and head south of the river. The South Circular was a poor relation, an inferior and unimproved cousin to the A406, running for most of its length on twisting, turning high roads through urban centres. South London has never received its due in transport terms - tube lines sputtering to a halt after barely crossing the river, railway stations closed and not often considered for reopening, and to cap it all a road network which struggles to support the population which it serves. I found myself curious about this southern exit and what it might reveal about areas I rarely visited, but, today my business was with the northern outlet from Chiswick Roundabout. It was an inauspicious start to this long journey - the footpath fringing a long-vacant, overgrown corner site and surrounded by a cluster of roadworks where the traffic funnelled into a brief stretch of ageing dual carriageway. All too soon, the traffic was crunched into a narrow four lane, single carriageway suburban route between ranks of houses. A surprise for me, as I walked today, would be discovering how many people lived directly on the North Circular and would have to negotiate pauses in the torrent of traffic simply to leave their driveways. These roadworks appeared to mostly affect the railway bridge, leading over the inelegantly named North & South Western Junction Railway line between South Acton and Old Kew Junction, with pedestrians diverted over a makeshift covered bridge beside the road. The railways of this corner of West London are complex and trying to unravel them in my head without a map was folly - but I later recalled that this line was briefly used for the 'Crosslink' service from Basingstoke to Norwich via the North London Line, finally ending in 2002. A noble but ultimately doomed effort at using the existing infrastructure in new ways - a sort of Crossrail on the cheap. As I walked and pondered the railways criss-crossing the area, I stumbled upon the wild green edge of Gunnersbury Park. My first contact with this place was via a song, a rather twee piece by The Hit Parade, which made it sound an idyllic and rather ethereal spot. I'd always suspected however that the song was something less honest - the urge of a provincial lad freshly arrived in the city to namecheck a London spot near his newly adopted student digs perhaps? Let's face it - we just can't do road songs here. The romance of Americana doesn't translate into British suburbia, and even the most esoteric name-checking of places is going to sound gratingly odd. The reality of Gunnersbury Park was a surprisingly large tract of green space, some of which had been left to become pleasingly ungoverned and unkempt. Other areas, further into the park appeared to promise the usual range of facilities, and even a museum - but I didn't stray beyond the fringe. Instead I walked the pavement outside the high brick wall, noting how few gates opened onto the busy road. The North Circular here divided briefly into two carriageways once again, a run of large but, in their marooned and straitened circumstances, faintly ridiculous mock Tudor semis flanking the eastern side. This was, to some extent what I'd expected - and as I came upon the crossroads where this important route ground to a halt at traffic lights for the first time, I realised that the haphazard, piecemeal improvement of the route since the 1920s had turned it into a curious time capsule. Walking this route was archeology rather than geography. The silt-like layers of London's development had not settled evenly around the North Circular.

Shortly after crossing Pope's Lane and wondering if this was named for the pontiff or the poet, I entered the London Borough of Ealing by crossing the Piccadilly Line making its way out to Heathrow. I'd stayed near here before for a number of rail trips which had begun at Ealing Broadway, and there was a pleasant familiarity to Ealing Common which opened out to the west of the road, criss-crossed by pathways and flanked by tall townhouses. The tree-lined crossroads where I crossed the road out to Uxbridge, once the route of the old Oxford mail coach - was particularly familiar, and the hotel I'd used sat in its familiar spot on the northeastern corner, now a rather swankier Doubletree establishment. A local festival was setting up on the green. Ealing felt comfortable and promising in the morning sunshine. This is where Hanger Lane begins - and I confess I'd been a little disappointed by this when I'd first visited. If Chiswick Roundabout is the headline, then Hanger Lane was a depressingly familiar footnote to all the worst traffic reports, the place where all journeys collapse into epic traffic snarls. Hanger Lane even sounded gritty, dangerous and relentless. It was, in fact, a leafy continuation of Ealing Common - at least at first. The road climbed slowly initially, soon becoming surprisingly steeper - living up to the name's origins - a wooded hillside. Hanger Hill was once a desirable out-of-town spot, and even after the coming of the great arterial route of Western Avenue in the 1930s and the building of several suburban estates on its slopes, it remains a sought-after area to live. As I ascended the hill I noted a broad, well-trimmed but abandoned sports ground, once home to Barclays Bank's staff leisure facilities. The large modernist pavilion building crumbled in a corner, its bold clock face falling from the wall one modern, numberless hour marker at a time. I crossed the street here in preparation for navigating the junctions up ahead and found a crescent-shaped tangle of woodland separating the estates from the road. The woodland was refreshingly cool, with waist-high nettles and tangled brambles. I felt like I'd plunged into a forest, despite cars swishing by just feet away.

On emerging from the woods, the road started to descend into the wide valley of the River Brent, and the view which opened before me was less bucolic. Above the shimmer of fumes above the Hanger Lane Gyratory was a climbing terrain of suburbs and industry, the arch of Wembley Stadium dominant. The road reached its first major junction almost absent-mindedly - straddled by a parade of shops served by little sides streets, the confusing horror of the Gyratory came rather suddenly upon me. Marooned in the midst of the clamour was Hanger Lane Station, a sober concrete and glass drum peeking from the caldera in the midst of the giant roundabout. The network of subways serving the station also allowed pedestrians to access the various other exits, and I soon found myself on the north eastern quadrant of the junction, beside an almost identical parade of stores. That these shops could survive so close to the others was testament to how few people dared to venture beneath the junction perhaps? The A406 turned north east here, now becoming a divided highway in earnest with a solid metal fence preventing pedestrians from attempting a suicidal crossing. Walking the narrow sliver of pavement towards the fitful surges of traffic, I wasn't entirely sure the path continued ahead. So, after passing under the northern arm of the Piccadilly Line I used a brightly tiled underpass to reach the northern side of the road. The route here shares the broad valley floor with the Brent, and represents a northern boundary for the vast Park Royal business area. The area between the river and the road is a straggling mess of fringe businesses, marooned and separated from the main business park by six lanes of traffic. As such they're a strange bunch of premises: a furniture outlet with an impressive mock-colonnade entrance, a truly huge Chinese supermarket, car dealerships and a forlorn Travelodge surrounded by high fences and battered by fumes and noise from the road. Beyond this, a modern aqueduct carries the Paddington Arm of the Grand Union Canal overhead, but there is no easy access from this side of the road. Instead, stairs lead up to a footbridge suspended under the canal which allows pedestrians to switch from one carriageway to another by shuffling along under the towpath. The canal was a welcome thought - cool waterside walking was an appealing alternative to the hot dusty slog of the road - but it wasn't for today. Intrigued by the bridge I added it to my list of potential future urban hikes and moved on. Up ahead was part of the cultural history of the North Circular - The Ace Café. Opened in 1938, the Ace was a modern, bright transport café serving traffic on what was then a newly improved road with an equally modern bright future as one of London's future Ringways. The always-open Ace became a centre for motorcycle culture in the 1950s and 60s, featuring in the movie of The Leather Boys - a somewhat sanitised version of Gillian Freeman's novel of gay biker culture. Between 1969 and 1997 the building languished as a tyre warehouse and office, before reopening and once again serving the motorcyclists of West London. As I climbed up the curving ramps of the adjacent footbridge to get a view of the road, I saw ranks of motorcycles gleaming on the forecourt while speakers thundered out rock'n'roll and leather clad men sweltered in the humid late-morning. The Ace gleamed, pristine white plasterwork shining in the sun. There was something inspiring about seeing this bit of road culture surviving, a world away from the monotony of motorway service stations where you needed to check the signs because you could be anywhere. The Ace anchored the corner of the North Circular as it began to head east into uncharted territory. My footpath descended to pass under the first of numerous railway arches, the North Circular using its own, pedestrian-exclusive concrete underpass here. The service road I was using here was the entrance to Stonebridge Park station, and also to both the rail depot and Princess Royal Mail Distribution Centre. Between the bridges, looking up into a narrow band of sky, I caught a glimpse of Stonebridge Park signal box sitting high above me between the lines where Overground and Bakerloo Line trains shuddered overhead. Aside from the frequent passage of Royal Mail juggernauts, it was oddly cool and peaceful under the railway, and odd to think how often I'd passed above this otherwise unremarkable spot.

I emerged from the Victorian brick arches into a somewhat more dystopian vista. Firstly, I finally caught sight of the River Brent. Having walked in its shadow for some distance, the river finally came alongside the road in a deep concrete channel. I could smell the river before I saw it, a ripe sewage-like tang in the summer heat. Concrete walkways crossed the water to access the ground floor of Wembley Point, a 21 storey triangular tower which dominates the junction with Harrow Road. Now in mixed use, the curious ribbed concrete is clad in glistening mirror-like panels, reflecting the less salubrious view of the derelict Unisys Towers which sit on the southern side of the road. These curved concrete slab blocks have been out-of-use for more than a decade, despite various plans to reuse them. They tower over the surrounding low-rise suburban landscape and give the junction an air of the slightly off-kilter view of the future city which would have featured in mid-century science fiction. They are though, not entirely deserted, as an enterprising security guard appears to be allowing Wembley-bound punters to park within their fenced compound for a nominal fee on event days. Needing sustenance I decided to stray briefly from my route here, following Harrow Road into the almost disappeared suburb of Tokyngton. Everyone refers to this part of London as Stonebridge - or even just Wembley - but it is a distinct area in itself, even if remembered only in the name of streets and nearby parks. At first sight it's a fairly down-at-heel neighbourhood, with a long straggle of ethnic supermarkets and newsagents along the road. Two things quickly became apparent here - that I'd need to pay for my goods in hard currency rather than plastic, and that if I wanted to withdraw cash to do so I'd be paying for the privilege of accessing my money. It struck me how inequality is thrown around as a lofty, political concept just now - often measured by the gap between the ludicrous and unreal world of the football star and the rest of us - but that it really bites on this micro level. You've worked hard at a minimum wage job but to access the funds you earned in your local High Street you're paying almost a third of an hour's salary. It is perhaps this kind of built-in unfairness - high prices for pre-paid electricity, high credit charges for insurance bought in instalments, and so on - which makes the simple mechanisms of life more expensive for those who are just about getting by. Perhaps before we talk about levelling the pyramid, we should address some of this simple, functional inequality of access and actually impact real lives for the better? In the end, I left Tokyngton without making a purchase, striking out into the park which runs between the Brent and the North Circular here. Being near water, however noisome its aspect, took the edge off the increasing temperature and for a while at least my walk was surprisingly peaceful and cool. I'd planned to consume refreshments in the park, but the difficulty of buying anything on Harrow Road had scuppered that plan. Instead I ambled along, trying to capture a view of the looping arch of Wembley Stadium across the tree line. Eventually though I was faced with a choice - follow the river north, or head back east onto the road. Again I stayed loyal to my plans and found myself once again on a narrow pavement in front of small semi-detached houses which were spattered with road-grime and greyed with years of accumulated fumes. The front gardens were litter-traps, swirling discarded detritus from the passing cars trapped inside gates and along the fence line. While it seemed like a miserable existence in some ways, all of the houses were occupied and any sense of the widespread planning blight along the route which I'd read about seemed to have been driven out by the bizarre conditions in the London housing market. If this was a bargain in a relatively central zone, perhaps the endless churn of traffic out front was tolerable? Up ahead, the bright blue hulk of IKEA filled the horizon. I contemplated a visit to a strange drive-through McDonalds housed in an oddly charming red-brick roadhouse, but seeing it teeming with young families, I decided to press on towards the retail park. Finally, by way of a complicated footbridge beside the turgid, algae-filled waters of a channel feeding the Grand Union Canal from the River Brent, I found my way into a ridiculously big Tesco store. It wasn't the picnic-spot I'd hoped for, but it would suffice in a pinch. It seemed an appropriate roadside halt on the modern North Circular, where you're never far from a retail park.

Refreshed but still weary from the heat, I retraced my steps out to the North Circular. Immediately the road began to rise towards a railway bridge crossing the Chiltern Lines and the Jubilee Line. Almost directly below the bridge the lines diverge, with the broad fan of sidings entering Neasden Depot spreading to the north of the line. Pedestrians were relegated to a separate bridge on each side of the main span, the result of some earlier widening scheme. Somewhat isolated from the traffic I was able to scan the horizon, watching trains shuttling into the depot and trying to make out the various routes which split away here. As I rejoined the carriageway the road took a treacherous bend to the left which created a continued screech of brakes and a forest of red tail-lights. Almost immediately on turning the corner, the road became the frontage to another stretch of grimy but clearly occupied houses and tired businesses as I approached Neasden. Neasden is the butt of a series of Private Eye jokes - and it has ridiculousness built in from it's origins - deriving its name from 'nose-shaped hill' was never going to make it a serious contender. It was immediately clear that the substantial suburb has had far greater injustices done to it in recent times, with Neasden Lane - its main thoroughfare - divided by the North Circular into two distinct and disconnected parts. The urban centre is now bypassed by a busy underpass which linked into my route via a looping, part-cloverleaf junction squashed uncomfortably into the tiny corner of space available. The pedestrian route appears to take a long detour north, but I noticed the continuation of the path beyond a low barrier ahead and took the chance. I'm not alone, it appears to be what the locals do here too I could see, but as I cross above the bypass I spot the unedifying sight of a crumbling brown sprig of memorial flowers cable-tied to the safety fence. South of the road, the buildings along Neasden Lane stack higher as it climbs towards Dudden Hill and the green and white sign of 'Dicey Reilly's Nite Club' reminds me that this swathe of North West London, stretching roughly along the route of Roman Watling Street is home to arguably the most concentrated population of Irish folk outside Ireland. It's written that these northwestern districts were as far as the newly arrived young Irishmen could walk from Euston with their suitcases, and thus they settled here. They were indeed primarily young men - idealistic and keen to retain their culture despite needing to travel for work - and this meant that over the course of the 1970s and 80s the area took on a dangerous edge as the 'troubles' once again crossed the Irish Sea. Though primary accounts are unsurprisingly scarce and somewhat unreliable it seems likely that the area was a reliable source of funding for Republican groups during the most intense periods of conflict. While the enclave which once ran from Cricklewood to Paddington along the A5 is much diminished - in no small part due to the improving fortunes of the Irish economy in more recent times - it's a telling statistic that the London Borough of Brent still has a population of which 13% consider themselves Irish or of Irish descent. Looking along the divided community of Neasden straggling along the ridge it's hard to see the attraction to the area in some ways - but the promise of work, money and kinship was surely a strong draw.

The road began to turn east - and while it was still far from its most northerly point here, I sensed I was heading into more familiar territory. In fact I soon found myself close to the origins of a recent walk, as I arrived at the junction with Aboyne Road where a nondescript metal gate led into the parkland which separated the North Circular from Brent Reservoir. Slipping into the park I weaved around a gaggle of mothers applying sunscreen to their pramloads of children, and made for the water. The impressive sweep of the artificial lake stretched north and east, while beside me an earth bank marked the line of the dam wall where the waters of the Brent were stopped up. A busy marina filled the southern part of the reservoir, while wilder parkland was evident on the northern bank. I followed the rough path along the edge of the lake stopping to decipher the faded interpretation panels which had all been overwritten with the word 'ALLAH' in thick, black marker pen. The narrow stretch of grassland between the road and the water was a sea of wavering reedy grasses which swished pleasantly, altering the incessant traffic drone which I realised had dominated everything I'd heard for the last few hours. The path began to swing back east towards the road, and delved into a rather forbidding patch between tall and straggling trees. A pair of stolen suitcases had clearly been rifled through and discarded here, the odd ephemera of a holiday scattered disconcertingly among the branches. The path abruptly stopped at a bleak iron gate near a footbridge, depositing me directly onto the road once again. Dust and litter swirled around the alcove formed by the bridge abutments and the gateway. I wondered if it would have been possible to continue to strike out along the shore of the lake, finding my way out to West Hendon where I'd tried to access the waterside a month ago? It certainly didn't appear so - once again the North Circular was the only viable option. It is just that kind of road, it seems: a route of last resort.

I consoled myself in knowing that the River Brent wouldn't ever be far from the rest of my walk today as I slogged along the footpath beside three lanes of traffic which pulsed oddly between slow jams and high speed dashes in reaction to unseen traffic signals ahead of me. While I was focusing on the presence of the river, it was the road which would be the dominant feature of the next section of my walk as I approached Staples Corner. Here, the A5 crossed under the North Circular which rides high on a viaduct crossing the embryonic slip-roads of the M1. It's a complex mess of additions and improvements from a motorist's viewpoint, but from a pedestrian's aspect - you may as well not even try. Certainly it's clear that few do come this way, as individual footprints were evident in the thick layers of dust and detritus deposited on the footbridges which thread between the complex infrastructure of the junction. First I descended as the A406 rose between two totemic advertising pillars which dwarfed the surrounding warehouses, forming a ceremonial gateway to Brent Cross. Now at ground level, I passed under the concrete bridge carrying the A5, suddenly rather conscious of the towering stack of carriageways above me. A footbridge climbed from each side of the junction to meet in a central walkway suspended under the viaduct carrying the North Circular above everything. The competing streams of traffic shuddering around me created an impossibly complex sound which was at once both overwhelmingly loud and strangely soothing. It also had the odd effect of negating the sound of passing high speed trains on the Midland Mainline which also somehow squeezed through the junction on an old brick viaduct. As I descended to the ground on the other side of the roundabout, I faced a choice - follow what appeared to be a path under the railway or head along a side road which had been appropriated by a car maintenance establishment as an unofficial repair yard. The path soon ran out, depositing me in a position where I couldn't cross the next road which was effectively the beginning of the M1 - so I dutifully retraced my steps under the clammy arches and doubled back through the makeshift car lot, surprising the locals who clearly saw few pedestrians here. Finally I found the grubby, litter-strewn spiral ramp leading up onto a footbridge into the middle of the next huge roundabout. I was aware that I was sweating and breathing hard. The air was hot, dry and metallic and the mental effort of trying to find the right route was equally taxing. I had a dull headache and realised that my brow was fixed in a serious frown from trying to understand and negotiate this route. At times like this I suspect most people would wonder why I set out on these journeys? Why I wouldn't just get the next bus out of there? But my battle with Staples Corner was all part of understanding the terrain. There are always ways to walk these places, if you're persistent - and foolhardy - enough to seek them. As I trudged down the slope of the footbridge which brought me back to ground level beside the North Circular once again, I noticed that over the fence was the fringe of a vast car park serving Brent Cross shopping centre, the ungainly stack of buildings which glowered in the middle distance. I set off again, noting that you'd have to be pretty unlucky to need to use a space this far from John Lewis...

Passing Brent Cross took quite a while, the site straggling along the North Circular and almost using it as a breakwater to separate the shopping centre from suburbia. The margin which runs along the road is a little unloved, and perhaps not the face the stores would expect arriving customers to experience first - but almost no-one ever arrives on foot via the A406 I suppose? The long, dusty concrete service road reeked of misconnected sewage outlets and was strewn with litter from the main road while the fence was a trap for the slightly better class of rubbish blown away from the shopping centre. The layers of trash met, plastered by the breeze onto the high, mesh fence. The Fire Escape route from the semi-permanent funfair which occupies the space between mall and road was propped open, staff furtively smoking in the gap. An overloaded white Transit van attempted a three-point turn, its rusting and overtaxed bodywork almost grazing layers of rubber from the tyres as the driver swore at her inability to manoeuvre out of this bind. The Brent had been hidden inside the confines of the retail park for a while, flowing beyond the fence, but as the road curved towards its multi-level interchange with the A41 up ahead the river was again alongside the path, a deep concrete ditch lined with a glutinous layer of slippery weed and algae. I picked a way between the carriageways, not made easier by the only available signs assuming I wanted to access either the retail park or the oddly isolated branch of Toys'r'Us marooned to the south of the road. I eventually escaped, passing a rather fine old bridge over the river which was hidden beneath the dual carriageways, onto Shirehall Park which formed the spine of a decent estate of suburban houses shadowing the Brent and the North Circular. A little way further on I was able to escape the road briefly by turning into Brent Park. This sliver of wild green space follows the very first section of the Brent and the path here forms part of the Capital Ring. As such, it is at least reasonably clearly identifiable and decently kept - but it was today entirely deserted, which was perhaps not entirely unexpected. While some sections of the Capital Ring are popular in their own right, only the dedicated who intend to make the full circuit end up covering these suburban and more prosaic sections. They're missing a treat in my view - the park was cool and green, and while the shudder of the road was still evident, there was a welcome and peaceful division between traffic and footpath here. The path curved around the quiet and still Decoy Pond before heading back out towards a side-road, continuing after a crossing and a few metres walk on the pavement. And so I found myself at the beginning of the Brent - the confluence of the Dollis Brook from the north and the Mutton Brook from the east forming the rather larger river which heads south and west towards the Thames. My path lay along the Mutton Brook, passing through a tidy and well-used playground but lined with signs warning me not to enter the brook's polluted waters. Worryingly, the signs appeared to have been there for quite a while. Little had changed for the rather forlorn, reeking ditch beside me it seemed.

My path, and the Mutton Brook, passed under the thundering and shaking North Circular via a tiny tunnel, before emerging on a wide slope of grass falling away from the road as it turned east to use the brook's steeply sided valley to progress east. Walking below the road, guided by the tall gantry signs for its own impending confluence with the A1, was a surprisingly pleasant way to cover this section. Along the road a range of large, mid-century apartment blocks imposed their presence, forming the edge of suburban Finchley. I was overheated and tired, and it was with some reluctance that I scrambled up to the road again near the vast Kinloss Synagogue and once again found myself on the deserted and rarely-walked pavement beside the A406. The complex junction with Falloden Way was clearly a major pinch point on the route, as traffic was forced to a juddering halt at traffic lights. The Mutton Brook and the footpath continued as the Dollis Valley Greenway towards Hampstead, but my route lay further north. Noting the special 'hands-free' pedestrian crossings installed to let orthodox jews reach the Shul without operating machinery on the sabbath, I steeled myself for a final push along the road. The North Circular was again an urban motorway - its carriageways divided by a solid crash-fence which was carefully pitched high enough to prevent ill-advised unofficial crossings by brave or foolhardy pedestrians. The pavement was littered and broken, clearly rarely used aside from the sections near bus stops. I began to wonder about the wisdom of starting this walk - feeling painfully aware that I ought at some point to finish at least one of these odd projects which I begin so publicly. The temperature was above 30º and I felt far more fatigued that I'd expected at this point in the walk. Everything I was wearing was drenched with sweat, and there was a film of dust in my mouth with an unpleasantly grimy taste. Fortuitously, a green strip appeared between the path and the road, where trees leaning over from the green space on the edge of a housing estate, shielded me from much of the sun. Grateful for the shelter, I put my head down and walked - determined to get as far as I could today to improve on what I felt had been disappointing progress. Looking up as the path rose, I realised that the red-brick walls beside the road were familiar - and as my path climbed away from the traffic I noted I was at the point where the A504 crossed above but didn't intersect with the road - a spot where I'd been just a few weeks ago. The A406 entered its tunnel, pedestrians officially excluded - thankfully - and I crossed the familiar route near the bus turning circle and little garden where I'd paused so recently. I thought about giving up here - but I knew that transport options weren't ideal from here. Not least because I'd need to get back to this point soon to continue the walk. Instead I walked above the line of the tunnel, marked by the edges of the garden, and was soon descending again onto the deserted roadside footpath where a row of fir tree saplings struggled to survive on the grassy median. If they made it, this path would become an invitingly cool green alleyway - but now it was the same dusty swirl of litter which had typified much of my walk today. The path wove around the ramps to a footbridge leading to the suburban streets away to the south, and then crossed the forecourt of a BP garage. I could see that up ahead the path entangled itself confusingly between the slip-roads leading to the A1000 - the route of the original Great North Road before the new A1 was constructed. This seemed like a fitting place to leave the North Circular for now, and I gratefully snapped a picture as a reference for my next walk, before following the curl of the path to the bus stop on Squires Lane. I was aware while waiting in the surprisingly busy bus queue that I was drenched, red-faced and grimy from the road - but I'd also completely stopped caring. I found a seat on the mercifully cool bus to Highbury and Islington and pondered my next move.

Reflecting on beginning this perhaps absurd project, I realised that it had been on the cards for some time - it had begun with my frequent encounters with the North Circular on my walks, and was cemented by my curiosity when regarding the mysterious Rookery Path in Woodford at the end of a recent trek. Indeed the whole concept of my ill-conceived London's Other Orbitals project meant that I had to do this at some point. If there were paths and parklands, triangles of open space and curious river valleys along the way, it would make for an interesting journey crossing suburbs in a way that almost no-one would normally choose on foot. Attempting it on one of the hottest days in an unpredictable summer was perhaps a mistake - but I have to take my chances, and my walks, when I can - and perhaps there were no perfect conditions to attempt something like this? In any case, I was glad to have left the dusty, noisy road for today - but I was oddly drawn back. The next section would link together new vistas with parts of the route I'd already visited and that was oddly appealing. As my bus rumbled south, crossing the busy and colourful churn of Seven Sisters Road, I felt an awfully long way from the primped, managed banality of the Chiswick Park office development where this had all begun. Despite the trials which this first section of the North Circular had presented, I was strangely excited to get back to the road soon. A little later, as I idly researched some of the areas I'd walked on the train home, I stumbled across a passing mention of Louis MacNeice and finally, after a good deal of digging, I found the brief quotation below among the text of the long poem. And with the thrill of a new discovery of something which had - to me at least - lain hidden, there was no doubt I'd see this walk through.

The next day I drove by night   Among red and amber and green, spears and candles, Corkscrews and slivers of reflected light   In the mirror of the rainy asphalt The North Circular and Great West Roads   Running the gauntlet of impoverished fancy Where housewives bolster up their jerry-built abodes   With amore propre and the habit of Hire Purchase. The wheels whished in the wet, the flashy strings   Of neon lights unravelled, the windscreen wiper Kept at its job like a tiger or a cricket in a cage that sings   All night through for nothing. Factory, a site for a factory, rubbish dumps,   Bungalows in lath and plaster, in brick, in concrete, And shining semi-circles of petrol pumps   Like intransigent gangs of idols. And the road swings round my head like a lassoo   Looping wider and wider tracts of darkness And the country succeeds the town, and the country too Is damp and dark and evil.Louis MacNeice - Autumn Journal (xiv) - 1939

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here. The walk continues here.

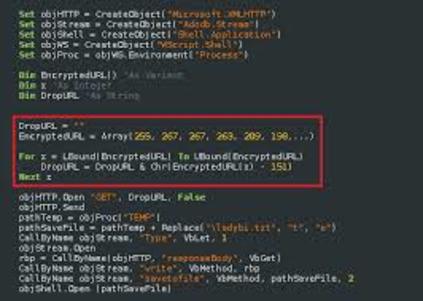

It's been a tricky week for a number of reasons - while Inspectors stalk the corridors of my office and I wrestle with seemingly deliberately obtuse bureaucracy at home and at work, someone decided that I was good for a few Bitcoins of ransom for my data. Linux ransomware is rare - but does exist in the wild. It's also been fairly primitive up to now, with attackers using predictable keys to encrypt data, and generally showing a lot less knowledge of the underlying system than the Windows based machines they're used to hobbling. However, as much of the world's larger-scale server architecture lives on some form of Unix derivative, they're going to get better at this.

My first question was why?, or more specifically why me? This is a completely non-commercial site, with relatively low traffic and which really only a few people would notice the absence of should it fall off the net - albeit after nearly eighteen years online! Anyone who knows me would know I'm certainly not good for the kind of ransom proposed. I cycled back through the various political disputes I've been involved in around the last election - none felt nearly sharp or potent enough to inspire this, in fact the whole campaign passed in a sort of stunned blur for both sides I think. I thought about other rivalries - I don't have many, and the one work-related matter which came to mind seemed unlikely. So perhaps it was just completely random after all? Just a chance attempt to extract a bit of cash from someone who rambles about roads and railways. Maybe. I think I'll have to accept this explanation.

The next step was recovery - and at first this didn't look remotely good. Hosting my own server has many advantages, but it means that anything which goes wrong is mine to fix in my own spare time - and that has been in short supply this week with all that's happening. It also appeared that the way the attack had progressed may have meant that the encrypted files had been backed up over the good ones. It was hard to say. In the end I decided that the best course of action was to completely reinstall a clean server and hope that the off-site backup was still good. Thankfully, the fact you're reading this shows that this strategy worked out - but not without some tribulations on the way. A lot of us keep servers running to the configurations we painstakingly worked out years back - and while they keep working because kind developers tend to value backward compatibility, a fresh install brings a new world of changed ways of doing things. I think, almost a week later, things work largely as they used to - with a few minor exceptions I'm still tweaking. Will they try again? Surely - but I hope if that happens, I'm ready.

Finally, I had to consider how my regime of backups worked - and the answer was actually, pretty well - I had a good, very recent, clean backup which was very easy to restore once I knew things were safe. But it could have been better - slicker, cleaner, more efficient - and the itch to polish and improve, to shave a few steps off there and make something work just a little better was suddenly back. In short, it's proved an interesting intellectual exercise which has distracted me a little from the rest of the week in generally positive ways. It seems likely that the vector of attack was a Wordpress installation which hosted my old Songs Heard on Fast Trains music blog. Certainly this has been attacked before, being used to relay spam via the injection of some malicious code. I've long disliked this blog being separate from the rest of the site, so it was time to extract the data and make it part of Lost::MikeGTN proper - some external links to SHOFT might break, but it was a small price to pay for closing a potential door. So, that's done too - and while this might need some tweaking and changing to make it look and feel right, at least it's here and you can still read my thoughts on obscure Scottish music of the early 2010s!

The loss of data to attackers from outside is always going to feel like an insult or an invasion, and as more of our life is lived virtually it will begin to feel more and more like a physical intrusion or loss. For me, the loss of a great deal of recent writing about my excursions felt potentially like a depressing enforced ending to a meandering project which I wasn't ready to give up on just yet. The older stuff, the diary entries from the late 90s for instance, perhaps only have any great relevance to me - but even so, the fact some of this digital archaeology survives makes it feel worthy of keeping. I almost lost a lot, but I learned a great deal more. And so to more turgid posts about long walks, observations on the rail network, and generally to more of the same...

Somewhere in the chaos and confusion of elections, referenda, terrorist attacks and transatlantic tumult in the last several years, HS2 has all but disappeared from the debate. This emblem of a modern Britain dragging itself towards the future was to scythe across green and pleasant England, linking London and Birmingham in hitherto unimaginably short journey times. Despite being a tiny country, we would finally reap the benefits of High Speed rail as a way of linking the metropolis of London with first the rapidly gentrifying Midlands, then the Northern Powerhouse. Eventually, it might even reach Scotland - still in the political sin bin for daring to dream of independence. For a long time, HS2 dominated debate - and in an odd precursor of Brexit it wasn't entirely cut along party political lines either. An MPs proximity to the line or its potential termini was a far better predictor of their view than rosette colour. The massive task of taking a project like HS2 through public enquiries, select committees and detailed planning hearings began in earnest and as the detail came into mind-numbing focus, the big picture disappeared entirely. The hearings and enquiries were utterly public and transparent processes, but the cloak of technical complexity is always much more effective than outright secrecy. Objectors became well-versed in environmental impact assessment, cost benefit analysis and property law while the rest of us just had to decide if it all sounded like a 'good idea'. I confess I was broadly in favour at the outset: I love trains, I'm a committed user of public transport, and I enjoy seeing technology advance. But the zones through which the line would pass, once it left Greater London in particular were a near blank for me. It was easy to dismiss as cartographic whitespace.

Finding an urge to colour in these gaps, Tom Jeffreys achieves something quite remarkable in Signal Failure: bringing the massive complexity of HS2 back to a human scale. He sets out to walk the route, scribed in lurid highlighter strokes across Ordnance Survey maps as a not-entirely-inaccurate approximation of how the line's critics imagine the line was planned. It should take him ten days, involve some camping out in the wild and bring him into contact with all kinds of characters who sit on the frontline of the debate along the way. It ends up being a far more complex proposition which examines the very nature of walking itself before Jeffreys finally reaches the Bull Ring.

Jeffreys is by trade a writer on art, and brings with him from that world two absolute gifts: an eye for beautiful descriptive detail which makes the waste incinerator at Calvert sound a sublime almost-equal to any view across the Chilterns, and genuine erudition which underpins his writing with detail and research. This is a surprisingly hefty book, and in the early passages where the nature of walking writers - and writing walkers - is examined, I started to feel concerned that this had backed things into a niche. However, these reflective essays are punctured by reality - errant horses, the hardships of camping, the treacherous nature of industrial cartography - which anchors them in a quest. A quest which Jeffreys self-deprecatingly feels he ultimately fails to achieve - but in unravelling the journey he introduces people who's experiences take HS2 from a conceptual diagram towards a future reality. There are the couple who didn't realise how desperate and suicidal the prospect of the line made each of them feel until they were interviewed on camera together, there is a naturalist who stands to see preciously guarded habitat riven by rails, and there is a cheesemaker who has been through this before: embracing change, diversifying to survive, revisiting the business model. Jeffreys' encounters with the wider public are perhaps more like my own when walking: suspicious, confused, somehow irritated that someone is stepping outside the normal boundaries. The walking writer is a figure of deep apprehension these days, and sometimes perhaps deservedly so.

Throughout the book, Jeffreys wonders about what he is writing - glancing off psychogeography but landing squarely between travel and nature writing on the shelf. The debate that squirms at the core of the book about nature, wilderness and human intervention finds its feet in the examination of these genre politics and I found myself genuinely intrigued by the history of older, extremely white men batting the future of the planet back and forth at length. It's important to remember to that these are, in principle at least, the people who agree we should act swiftly to save the planet! For his own part Jeffreys is, rather like me, not the kind of person who can name our flora or fauna, or who knows what's good to eat and what will kill you out there in the wilds - but his engagement with the kind of spaces we all experience, every day is challenging and inspiring.

Signal Failure is an impressive achievement - taking the walk and exploring not just the landscape and its people, but the theoretical underpinnings of grand projects like HS2 and their human and natural impact - but in a way which places us in a landscape from which we don't fully understand what we'll lose.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.