I left the bus at Limehouse Station - maybe it was the urge to get walking, or the curiosity which had managed to get the better of me? It's hard to say, but as I edged my way around the road crossings and under the brick arches which carry the railway and DLR overhead, I felt very glad to be back. I had half a mind to head for St.Anne's Church, with the lantern of Hawksmoor's tower glowering at me, stark white on the leaden sky - but I'd walked that way before and I knew that wasn't for today. Instead I wanted to skirt the river, striking a course across the top of the Isle of Dogs. My targets lay east of here, and the walk to get there wasn't planned or arranged at all - so I did what I always do, and headed for water. I've visited Limehouse Basin before - a fleeting circumnavigation during the summer of 2012 - but I'm curious to work around the perimeter again. Passing the lock which gives entry to the Regents Canal, I spot a curious statue on the skyline - Christ the Steersman looking out to the river and granting safe passage to sailors, or perhaps just regarding the tall crane which is building something to obscure his view? As I cross the entrance to Limehouse Cut I recall being harangued by a group of Spanish students here before. Today it's quiet, a solitary homeless man parked under the footbridge.

Here I decide to take a route slightly inland, along Narrow Street and Limehouse Causeway. I'm curious to follow the straightest path here, to cut a swathe directly eastwards as far as I can. This is largely uncharted territory for me, and while I've flitted around the river fronts, this stretch of remarkably well preserved warehouses and wharves is a mixture of the charming and depressing - which so often sums up gentrification east of the city. Every authentically painted wooden door gives entry to either a range of utterly unaffordable loft apartments or a faceless media company - some buildings hosting both. Do people live 'above the shop' here like they did in the 18th century, I wondered as I passed Ropemaker's Field by way of a larger-than-life statue of a Herring Gull. Looking north, a development of low-rise public housing was dominated by two stark, grey concrete clad blocks - Malting House and Brewster House. I marvelled that, although I'd passed on the Docklands Light Railway many times, these blocks hadn't ever troubled my view south - no doubt dwarfed by the massive blocks of Canary Wharf in the near distance, the eye drawn involuntarily upwards. At this point, my route headed inland while the Thames turned sharply south. I followed the railway arches towards Westferry Station where the tangle of roads roared in the near distance. Again on instinct, I stayed south of the arches, edging along the railway which I knew took broadly the path I wanted to follow. For a while at least I was separated from West India Dock Road by a large fitness centre which dwarfed the grand Dockmaster's House and a quaint row of brick cottages, marooned in the glass and steel landscape which was now surrounding me. At the end of my path I noted the huge triangular DLR junction looming on narrow concrete viaducts. The various extensions and additions to the basic three-way pattern soared and dipped over the triangle giving a crazy sense of distorted geometry. The path ended at the cul-de-sac loop of Hertsmere Road. A black Mercedes was parked across the pedestrian access onwards, rear windows tinted, driver wearing sunglasses. I passed the car and edged around the rear to access the path. Clearly but inexplicably irritated he glanced in his mirror, started the engine and sped west with much noise and tyre-screeching.

I emerged from the tangle of railway viaducts onto a path beside Aspen Way, the busy six-lane arterial which scythes across the top of the Isle of Dogs, taking traffic from the Limehouse Link tunnel to the Lower Lea Crossing. It was moderately busy, providing a shrill metallic soundtrack to this part of the walk. I crossed the entrance to the Canary Wharf development - a permanent security checkpoint, manned by uniformed guards in Police-grade stab-vests. The guard was busy instructing a wayward wanderer in how to get back to civilisation when I passed, and I couldn't help suspecting I'd have got the same treatment had he not been busy. Shortly after crossing the entrance, a marine aroma announced Billingsgate Fish Market. This 'new' site, no doubt chosen back in 1982 for its relative distance from polite city life was now nestled at the foot of banking towers and expensive apartment blocks. It presented a strangely swift transition to the ragged margin of the Isle of Dogs, the development suddenly petering out into wasteland carparks and recession-paused building projects. Over it all, One Canada Square and its sister blocks glint and reflect the view back at the pavement. There was no-one around on a grey, windy Saturday morning - neither banker nor fishmonger - which just made it all feel even stranger.

Here I had to brave a complicated road crossing, feeling thankful for the sudden eerie quiet which descended on the street once I'd passed the Market. Diving under the flyover I emerged not far from where my previous walk had begun on Poplar High Street. Once again skirting the bulk of Robin Hood Gardens, I found myself disappearing between the undistinguished buildings of the East India Dock Development - an enclosed loop of buildings, turned inward for protection from the flailing economy of the early 1990s. The Borough of Tower Hamlets has leased part of this complex at tremendous public cost almost since it was built, and no-doubt still will unless their ever-wayward Mayor gets to realise his ambitions for the former Royal London Hospital buildings. The streets hereabouts all bore the names of spices - the stock-in-trade of the East India Company - and the area still had the feel of being held in bond. Lifting gates and security kiosks bookended a bus stand, the vehicles allowed through under sufferance. I tried to look as innocuous as possible as I stalked purposefully along Saffron Avenue, a rank of gently ticking 277 buses resting, their drivers relaxing in the deserted calm of this spot at a weekend. Emerging onto the public highway at a large roundabout, I spied a service station up ahead. I was hungry and thirsty - ever aware that my decision to start my walk further west meant I'd yet to even begin to achieve my goals. I ducked across Silvocea Way, passing the mighty red brick dock walls which marked the site of the former Pepper Warehouses, and entered. It was a strange amalgam of convenience store, urban coffee outlet and filling station which appeared to expect customers to pay for different commodities at a series of different checkouts. I made the simplest circuit that I could to obtain coffee and food, and retraced my steps to the Dock Walls, disappearing through the portal flanked with the emblems of Mercury, protector of merchants and tradesmen. At last, a broad, open view across Bow Creek greeted me. It was time to rest and take stock of my walk so far.

After a brief detour to view the dramatic curve in the river here, I pressed on. My first objective was just across the water, but was still a short walk away along the river path. The west bank of the Lea has been improved here - a wide expanse of footway, benches and lamps edge north towards a tangle of bridges - but the scheme is unfinished. This abandoned attempt to make the river walkable to its mouth would return to confound me again and again today. Not even the mighty juggernaut of the Olympics or the seemingly omnipotent reach of the LLDC seems able to push this project forward. What has been built though is the 'blue bridge', or more formally the Jubilee Footbridge. This stocky, imposing crossing is a little lost between the ghosts of other crossings and the massive road scheme which takes the A13 over to Canning Town, and as a result it has a curiously abandonded feel too. Litter drifted across the path, and the ominous sign told me that there was a "Pollution Control Valve" nearby if required. South of the bridge, the old iron railway swingbridge remains intact but decaying. I wondered why it wasn't pressed back into service to get walkers onto the peninsula rather than building a new bridge? North of the blue bridge, the road bridges swung away to the north east a little - an impressive iron structure from 1935 sandwiched between two concrete slip-roads and bus lanes commissioned by the London Docklands Development Corporation. Descending towards the park I noticed an elegant sweep of red brick with a steep slope down to the bank - one of the abutments of the 1896 replacement to the original 'Iron Bridge' which carried Barking Road over the creek remains here, sandwiched between new crossings, filling with litter and looking forlorn and forgotten. I marvelled about this tiny reminder of the past importance of this spot, left to obscurity here. Turning south, the gates of Bow Creek Ecology Park were before me. This tongue of land, pinched by the bulging turn in the river, had been given over to nature once the DLR viaduct had been completed, and was now open as a public park. It was, predictably, deserted. A DLR train descended from the viaduct, touching ground just feet from where I stood - the disinterested faces of the passengers on board looking blankly back at me. I walked the well-kept path around the loop, seeing places I'd already walked from new perspectives across the water. The overcast skies broke a little and afforded me some sunshine too. On the eastern side of the park, a view across to the City Island development showed progress - with the new, red, high-level footbridge in place but not commissioned up ahead. I reached the end of the path. A footbridge carries a path over the DLR here from the entrance of the Ecology Park to the eastern side of the tracks, but the way forward was barred by railings. I surveyed the footbridge, wondering if doubling-back and taking that route would get me further, but in the distance I could see more barriers near the new high-level bridge. Once again I cursed the lack of a continuous walkway along the bank.

Forced to retrace my steps, I pressed on past the blue bridge and walked along the road access to the park. The DLR swoops upwards here to reach a former railway alignment, and Wharfside Road passes under it in a spot I think I can declare the worst place in London bar none. As the underpass is too low for vehicles, the road travels in a hollow channel dug deep between two raised footpaths. This gives the pedestrian a dark, claustrophobic experience, hemmed in by railings and roof, with the echoing chasm of the road beneath. The whole area is a swirling trap of litter and dust. Dumped chemical barrels and the ragged remains of rough-sleeper's bedding are strewn across the path. The opposite pathway is perhaps worse, stopped off at one end by railings, it is an even more popular haunt it seems with syringes and special brew cans littered across the concrete plinth. But worst of all, it is oddly, eerily silent here between passing trains. The remoteness and deserted nature of this spot is no doubt its attraction for many of its regulars, but right now it was perhaps fortuitously empty of any obvious signs of life. I moved on hurriedly, out into the dusty mess of Stephenson Street, running alongside the Jubilee Line. I'd seen this long, straight stretch of road from the train many times and wondered about it - particularly the Durham Arms. An apparently closed, crumbling traditional pub which sat among factories and makeshift corrugated iron yard fences. Clearly older than most of its surroundings it must once have been busy with dockers and local workers, but now it was marooned between river and railway. Amazingly though, it was still open. Through the grimy, stippled glass windows a dull light glowed. A notice threatened dire consequences for incorrect parking, and another suggested - as I skirted an inflated and bursting steel drum of some sort of foaming chemical dumped on the path - that I try the beer garden at the rear! I didn't, but looking into the history of this place later, I almost wish I had. Linked to the shady past of the area, once owned and operated by the Sabini Gang, and later operated by the Metropolitan Police to front a secret corruption investigation, this was far from an ordinary boozer. The only traffic here was a constant stream of "out of service" buses thundering in and out of the nearby depot. As I paused to look along the long, dusty line of the street, a bus halted beside me and the door opened "Are you lost mate? I can take you back to the main road if you want". I was almost tempted, this wasn't somewhere to linger. But I had further to go yet.

At this point, things began to get frustrating. My feet had entered the strange zone which all urban walkers will know - where stopping was advisable, but starting again would be unlikely. I'd noted a range of possible footpaths to the river, linking Cody Dock with Twelvetrees Crescent, but the map was unclear on whether there was a way through. This whole stretch of the Lea was to be linked to Stratford by "The Fatwalk" - a shared pedestrian and cycle facility - in a plan dating back to before the Olympics. The games briefly re-energised the plan, and bits of the route have appeared, but crucial chunks are missing. The project is now once again shelved, and as a result I found myself picking my way around an industrial park, deserted save for a young eastern European couple who clearly had hoped to find privacy and were mildly annoyed to find me lurking. The businesses here were a little more salubrious than those I'd passed on Stephenson Street, mostly large national or multinational outfits. After what seemed like an interminable walk between these vast prefabriacted warehouses, I found the gates to Cody Dock resolutely locked. This is an interesting spot - a social enterprise has secured ownership of a small dock which branches off the Lea nearby, and runs projects and events on the premises. They hope to raise money to replace a bridge over the dock to link with the very path I wanted to access. But today, no chance of getting through to even see the progress. I retraced my steps and turned north into the Prologis Distribution Park, passing a deserted security check to enter. This was another odd space - apparently public, with bus stops and pathways through, but assuredly private as the Security Office and uniformed guards made sure passers by were aware. I walked through the park to reach its north eastern extremity, where there was the suggestion on the map of a path running beside Abbey Creek and the Channelsea River. Once again, I found my way barred by a semi-permanent fence. This was becoming all too predictable. Again retracing my steps, I caught sight of the statue of Sir Corbet Woodall surveying the towering gasholders which his company had built from a pleasant little woodland nook in the midst of all this industry. Thwarted again, I headed west, crossing the Lea at Twelvetrees Crescent where on a previous walk turned back because of the security presence, assuming there was no public right of way over the river. From the middle of the bridge, while looking over at Bow Locks, I spotted the pleasant, riverside walkway along the eastern bank which had been constructed as part of the planning gain for the nearby new industrial units and which would, if the plan ever came to fruition, link Cody Dock with Twelvetrees. I didn't have the heart to walk that dead-end today - there had been one too many frustrations to my progress already.

On more familiar territory now, I figured it was time to use my local knowledge a little. After a visit to the supermarket, I returned to the river at Three Mills, pausing for refreshment and a rest. As I sat, unkempt and fatigued, poring over my 1972 A-Z for clues, a group of senior walkers turned up and sat nearby. All greying, but bursting with almost indecent fitness and well-being, they carried all the appropriate gear - modern maps, good boots, spiked walking sticks and a sensible packed lunch. As I furtively fished in my Tesco bag and tried to make sense of the map which was the same age as me, I felt them looking at me with curiosity, maybe a little distaste and perhaps some pity. It was time to move on. I turned east again, onto Three Mills Island, in the hope of either finding a path around the back of the House Mill and turning towards Abbey Creek, or crossing the Prescott Channel at Three Mills Lock and picking up the Long Wall path. Both seemed unlikely - the path around the mill was stopped-up at its entrance, so I crossed into the pleasant but quiet park and walked to the lock instead. The bridge here had been closed when I first visited in 2012, and remained so. Across the water, work continued on the Lee Tunnel which seemed to be taking forever to complete. Getting somewhat used to finding the way blocked now, I recalled the route I'd taken along the Three Mills Wall River through the little residential estate to the Greenway, and decided to follow that. Today though I headed under the sewer and into Abbey Lane, passing a row of attractive workers' cottages, now relatively cut-off and sleepy since the road was severed. Here the continuation of Abbey Lane swings right, heading back towards Abbey Creek. With the impressive towers of the Victorian pumping station on my right I headed along the strangely busy road to a tight curve with a bridge parapet on one side. Crossing the fast-flowing stream of traffic and perching on the tiny sliver of pavement behind the crash-barrier, I looked over into the remains of the Channelsea River. In fact, long before I saw it, I could smell it. The combined odours of a long-since stopped up river and a major sewer flowing overhead just feet away were pretty overpowering. The Lee Tunnel works haven't only affected the Long Wall path it seems, with the Greenway also closed between the two points. The sewer, scaffolded and plastic-sheathed, shadowed the mud, silt and filth below. The Channelsea is gone. A ghost of a river, filled in in the 1970s, and now I wanted to walk the path which had been laid on top. I'd finally found my second goal.

The Channelsea Path, although I'd walked a long way and taken a ludicrously convoluted route to find it, was a pretty unremarkable walkway. From its terminus on Abbey Lane, in less complicated times it should be possible to ascend to the Greenway, or even join the path to Three Mills via the Long Wall. But for now it comes to an abrupt halt here at the busy curve in the road, Disappearing between trees, it follows the line of the street initially, with the Jubilee Line's Stratford Market Depot fanning out in the space between the former river and Bridge Street. Soon, with the road giving way to the back of large industrial units, all is quiet. The former river walls, green with moss and dotted with occasional ironwork appear on what would have been the western bank. A tiny brown rat scampers out into the path and eyes me suspiciously, before scampering into the undergrowth and shadowing my walk - presumably hoping I'll drop some scraps or litter, as it seems many have before me. Otherwise I'm alone, walking slowly but purposefully, occasionally stopping to investigate the fading public art or the information boards which are still just about readable, giving context to this path and its history. Sooner than expected, I find myself deposited into a new development of homes, just off Stratford High Street. I've survived another excursion off the map, and I'm back in civilisation almost sooner than I'd hoped.

After a brief coffee stop in the colourful, dizzying whirl of the Stratford Centre, I hopped on a bus back west for a final quest. Someone had tipped me off about the location of some graffiti related to saving bees, and I was keen to see if it had survived over-painting. I disembarked at the East London Mosque and crossed the street onto a narrow strip of pavement created by the Cycle Superhighway improvement work. Fighting my way along the contested path, I finally turned into Osborn Street and made my way along an equally difficult-to-navigate Brick Lane. I somehow always feel like I'm walking against the crowds here, so I wasn't sorry to duck into the alley leading to the old Shoreditch Tube Station where I knew there was a fair amount of street art. No bees this time, but a chance to watch some artists working on a memorial to Sir Terry Pratchett which was taking the entire wall of the former station. Back on Brick Lane, I dipped into a bookshop to buy a card before again leaving the fray for the backstreets around the newer Shoreditch High Street station. Here I found where the bees had been, but alas new work had overwritten the landscape. The vacant plots of the former Goods Yard were fenced off and parcelled up for development now, and it clearly wouldn't be long before this sort of thing became more public nuisance than public art. Finally, after a day of idle threats, it began to rain at last. It was time to duck into Liverpool Street station and begin the journey westwards, and towards home.

Today had presented a strange mixture of curious finds, objectives achieved and frustration at the disconnectedness and fragmentary nature of the river path. While it felt like a privilege to share in the secret history of this sometimes overlooked part of London, it felt equally sad that an attempt to open this to everyone had once again foundered. Even more worryingly, where private space encroached on the riverbank, the path looked likely to remain severed with access controlled by bored, uniformed guardians who would pick a fight for sport. But just like always, this walk had suggested new turnings to take and different approaches to this part of the world. It's time to plan for the next trip east....

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Anyone who has even scanned in passing posts on this site alongside those on my old music blog will know that the past few years have been marked by two key obsessions... the tide of inventive and surprising music emanating from Scotland, and a ponderous but passionate exploration of the Lower Lea Valley. Anyone who has ever met me in person will equally be either amazed or utterly bored by my ability to flit between these subjects with equal fervour. So it seems impossible - or at least absurd - that these things should ever converge in any way. That's why I ended up writing in two separate places. And I suspet that's also why not too many people read what I write in either of them.

So it was both surprising and oddly validating to find this project. Surface Tension was commissioned by the organisation Thames 21 as part of their 'Love the Lea' campaign, and aimed to create a 'sound-map' of the river and its environs. Starting in Cheshunt, soundings were taken in the vast swathe of green that envelopes the river's manifold channels and diversions as it winds from its source to the Thames. As the river heads deep into the suburbs, and ultimately into the contested zone which I've spent my time exploring, various methods of expressing its presence were tried and tested: hydrophones dangled into Bow Creek, river water used to expose photographs, tape loops marinated in the chemical-rich effluent. Diversions were followed - Pymmes Brook and the various navigation channels explored - and the life of the river recorded. From the sound of Overground trains shuddering over low viaducts to football matches on the vast expanse of Hackney Marsh, the acoustic footprint of the river and those drawn into its presence in was catalogued and preserved.

When I first read about the project I was perhaps a little sceptical. Arts funding is ever more scarce, and it's hard to see how projects like this will become part of a permanent folklore beyond a funder's annual report. But then I spotted who was involved. Rob St. John is an Edinburgh-based musician who produced one of the most atmospheric, impressive and expansive records of the last several years in 'Weald'. One of the most intriguing abilities St. John displays in his work is how he connects music with place - the list of location-specific projects he has been involved in bears further exploration for sure - from the folksong of remote islands to the sounds of narrow Lancashire passageways. The idea of this strange link between music I've loved and a place I've reluctantly been drawn to explore so comprehensively felt just a little unlikely at first. How could this all link up so neatly?

But the end product is beautiful and oddly-hypnotic. A thirty minute trip along the river, set against a soundtrack of rare beauty. Flecks of guitar twine around loops of tape. Fragments of conversation and yelled football strategies disappear behind traffic and clattering trains. Pulses of electronica shift in and out of the frame. St. John's connections with Meursault and a range of other Scottish acts are exploited too - with Pete Harvey's cello and piano work slipping in during quieter passages - the river's ebb and flow of chaos and peace, purity and pollution marked by changes in the score. Quite apart from anything else, this is a beautiful piece of music which unravels its secrets with repeated listens. By turns relaxing and oddly edgy, it mimics the feel of a walk along the lower reaches of the Lea surprisingly accurately. While the composition - along with an impressive book designed by FOUND's Tommy Perman - sits as a remarkably coherent and enduring artefact of the project, intriguingly the project website retains all of the pieces of the assemblage as they were recorded - snatches of audio, photographs, maps and snippets of disjointed text. With these it's possible to reconfigure your own journey's along or across the river, to reassemble them to reflect a different experience of the curious and varied life of this remarkable and enduring waterway.

You can purchase the CD and book or digital download at Bandcamp, and you can find out more about the project including hearing the original sound recordings via a 'sound-map' of the River Lea at the Surface Tension website.

The day had a strangely unsettling start. Despite having very little time in their presence nowadays, as ever First Great Western have done their best to make things complicated. Today it's a lack of hot food, no working toilets and the promise of a 45 minute delay east of Reading. As it goes, the delay was resolved long before we got to that end of the line, and despite a little leg-crossing the journey was mostly relaxing. The slight frisson of uncertainty persisted at Paddington though - it was curiously busy, there were queues everywhere, and getting around the place was frustratingly slow. I finally found a quick, less than optimal breakfast, recharged my Oyster card and headed gratefully for the Hammersmith & City Line. On reflection, I think I was just eager to get moving - and rather surprisingly I felt a little nervous about the walk. I recalled how trips east of the city would sometimes feel strange and disconnected, how I felt like I was pushing at an invisible frontier. I also recalled that it was probably that very feeling which had kept me coming back for many, many years. In any case, I had a very loose plan and so far, the misty morning weather was mostly on my side. It was time to press on.

I surfaced at Aldgate, the city rising out of the mist to my right. I immediately turned my back on it - the lure of coffee and comfort was strong just now, but I'd planned at least the first part of my day and would inevitably berate myself if I didn't see it through. A few steps to the bus stop and onto a No.15 headed for Blackwall. We lurched into the traffic and turned onto Commercial Road. I'd walked parts of this route before - but my travels had criss-crossed the street rather than tracing it's path. This was, then, a rare pleasure - to take in this long eastern byway in relative comfort. The street is a weird mixture of bustle and decay, like much of the inner East End. A tumble of chicken shops, travel agents and dubious colleges give way to little gems of history, like the majestic Troxy - rescued from the inevitable fate of all such buildings - a Bingo Hall. Finally I found myself on more familiar ground in Limehouse, passing the former Town Hall and the grim white flank of Hawksmoor's St. Anne, before plunging into side-roads and emerging on Poplar High Street. Alert to needing to alight somewhere around here I let my instincts take over, and on sighting a Tesco Metro I hopped off the bus. It's strange - logically I know I'm in the midst of one of the biggest conurbations in the world and never far from food and drink, but something about these walks into the unknown makes me feel the need to stock up. Never wishing to be caught without the means of sustaining myself, I bought a few items and turned the corner onto the road as yet unwalked...

The meeting of ways here is a stark lesson in how planning can make life difficult. Passing the brutalist blocks of Robin Hood Gardens, still standing despite renewed efforts to progress their removal, I wandered into a complex mess of subways and paths which cut under and around a roundabout. High above, the Dockland's Light Railway crossed on a surprisingly elegant viaduct considering the heavy-handed nature of the buildings here. Looking up from this modern-day amphitheatre, all was concrete and glass. Cranes towered to the east, more dockland infill arriving soon - and to the west, the shining fascias of Canary Wharf reflected grey sky back at me. The tops of the towers were lost in low cloud, the pyramid atop One Canada Square coruscating as heat escaped from it's complicated internal systems. I wound around the roadway, rising south of the tracks with the former wall of Poplar Dock separating me from a classy marina development. I turned east, crossing the quiet street and delving into a mess of new buildings - half-finished mid-range hotels curved around a residential site nestled between the air intakes of the Blackwall Tunnel and a rank of earlier, dated looking housing developments from the first wave of Docklands development. I followed the road as it curved to run alongside Aspen Way, the arterial which delves under the remains of East India Dock in a nearby tunnel. Squeezed against the road and the DLR, at East India station I turned towards the River looking for open ground - more by instinct than plan - and found myself walking a long, straight avenue of trees with a metal line inlaid into the paving. A glance at the street sign explained things - Prime Meridian Walk. Looking beyond the avenue, I saw the ribbon of silver river, and almost floating above it, the bulge of the O2 in North Greenwich. I walked the line south, local and prime merdian converging at a gushing outfall of dubious aroma, the river shrouded and still. Cable cars edged along the wire to the east, while the baleful hulks in Docklands glowered from the west. It was here that I noticed for the first time that in a city of a rough eight-million or so, I was entirely alone.

It was a feeling which persisted for much of my walk in fact. I spend far, far less time alone now than I have for a very long time, and it was suddenly - almost pressingly clear that I was the only human being walking these paths today. Of course, every mirrored window of the expensive Virginia Quay development very likely hid another, possibly just as convinced of their solitary condition inside the insulated post-modernist block with the clouds pressing against the windows. As I navigated the river's edge via the silted remains of East India Dock basin a dog walker briefly appeared, crossing the park which was developed here to celebrate the turn of the last century. It remains as a monument to a previous era of hope and expectation - a "year of hope" totem inscribed with promises local children made to be harder working, better, more productive citizens sits beside an inert beacon - one of the chain which lit up the country at the appointed hour. Blackened and tired, it's corporate inscription lives on. I exit the park somewhat gladly - and delve between the high walls of former factories and yards which line the almost ridiculously misnamed Orchard Place. This twisting, narrow byway edges out to the very end of the peninsula separating the River Lea - or at least it's final incarnation as Bow Creek - from the Thames. Along the way, there is evidence of contest - a transport yard creaks and rumbles alongside artists' studios, a huge paper-clad fish dangles over 'The Causey' - a narrow, trash filled chasm which leads between buildings to river stairs. At the entrance to Trinity Buoy Wharf a decommissioned London cab sprouts a tree festooned with lights. They always said the artists would leave the Wick for Poplar - and it seems they're here before me. At the end of the road, the scene opens out into an expanse of dockside. The old lighthouse is one of the few permanent buildings here, beside a range of repurposed shipping containers turned into offices and studios. I pick my way between the parked cars and take pictures of the end of the Lea - the conclusion of a walk which I've never officially started. Across the river the metal works clatters and shudders. I find the cafe in a nearby container, it's outdoor area filled with objects reclaimed from the silt and mud. It's time to eat, grateful just to be among other people for a while.

Setting off again, I feel a little more adventurous. My feet are holding up well despite being so unpracticed, and the weather is at least consistent so far. I'd contemplated various options for the next leg of the trip - but the one which appealed most was to cross the Lea via it's last bridge. I'd checked variously via Google, and the Lower Lea Crossing was walkable. Indeed it had a broad, segregated cycle and footway beside its two carriageways of traffic. However, it seemed very few people actually did this. The ease of access by DLR and bus, and the strange lack of population in the immediate environs meant that this just wasn't a useful thoroughfare for pedestrians. As I retraced my steps and climbed up onto the pathway, I understood why. The road was quiet and empty, the hump of the bridge buckling in front of me. It was dry, dusty and windswept despite the damp stillness of the day. I climbed and surveyed the landscape - to the south, an elevated view of where I'd just walked. A forest of cranes, not from the long-deleted docks, but from the endless new identical blocks of flats being spawned along the river. Looking North, the oddly duodenal reverse curve of the Lea as it twisted onto itself, the empty isthmus of land earmarked as City Island rapidly growing into a small town in it's own right. Beside it, the dense green wedge of the Limmo Peninsula Nature Reserve supported the curving DLR tracks. Nearer to the bridge, the source of the dust - a Crossrail tunnelling site. As the road descended to the east bank, a scrubby embankment emerged. Just as I was beginning to feel once again that this was the least human place I'd walked for a long time, I spied a little well-worn pathway into the undergrowth. At the end of it was a makeshift den, hung with pictures and scattered with cushions. Someone lived here! Apparently undisturbed among the thunder of weekday traffic and the fumes of the nearby metal works. I mentally saluted them for surviving here, which felt like the very end of things, and climbed the stairs onto Silvertown Way.

As I descended from the viaduct near Canning Town station, I noted that civilisation was returning, albeit a very different one to that I'd left west of the Lea. Beside the road, the Canning Town Caravanserai project filled an entire vacant plot. Makeshift wooden theatres, play areas and restaurants crowded into the space - it was confusing and intriguing, and reflected the sort of community action which has quietly been happening around here for many years. This is an area where the mythical and the real East End collide - where waves of immigration wash on an overwhelmingly white, sometimes unwelcoming shore. Stereotypes linger in the heavy industrial air out here - at first I was amazed how many black cabs were ranked along the side streets, but then I realised that this is where the cabbies live. This is the honest, hard-working east which people tell you has long since disappeared. At the station I hopped on a bus to take me the short distance to Plaistow. It was walkable, for sure - but my feet were beginning to ache and I was aware that time was a far scarcer resource now these trips are much more infrequent. Weaving in an out of stops along the busy Barking Road, I alighted at Balaam Street and lurched into the suburbs again. A little way ahead, a rise in the road topped by a Pelican Crossing signalled the intersection with the Greenway - I turned west again, a little sadly. The temptation to pursue the path to it's distant end at Beckton was strong - but that's for another walk. This stretch of the path is less elevated and better used that the sections which I was more familiar with. Running between two sets of solid but ill-kept railings, the path crosses streets regularly at humps, a decorated metal arch welcoming the walker to the next long, straight section. Frequent cross-sewers join beneath the footway, denoted by a mass of gratings and a tell-tale whiff of decaying matter. At first the path was busy, but as I delved deeped into West Ham, the walkers fell away until I was again alone. Descending a slope onto Manor Road I realised that I'd been here before - the brief sense of familiarity disappearing as I turned north and set off once again along the long, walled chasm of the street as it wound around estates reclaimed from the ranks of victorian terraces.

Two tower blocks, Brassett Point and David Lee Point, lurched over the walls strangely and captured my interest. They stood out simply because despite the high density of life around here, there are very few tall blocks left. It's perhaps no surprise given the divisive nature of high-rise living in this part of London - the memory of Ronan Point is just a short walk away and ingrained in local legend. At the junction with New Plaistow Road I sensed a change again - the walk along Manor Road had been long and unusually warm in the February afternoon, but there was a chill wind whipping along this street of abandoned pubs and shuttered takeaways. The people are different too, and I'm aware that for the first time in a very long time in East London, there are only pinched, glowering white faces. This part of the world is culturally complex and highly contested - in the sense that there ever was a 'traditional' East End of cockney tradition, it was probably here - but anyone who scratches the uneasy surface knows that the real tradition here is of waves of immigration and - when things work - integration. Frighteningly, the thing which threatens this long-standing and uneasy equilibrium is opposition to immigration itself. The fear of difference, whipped up by odious cartoon right-wingers, is making integration harder and harder and creating the very difference which scares them. They're fuelling their own noxious fire, and here on the unassuming, practical face of things, I hear passing conversations about UKIP, 'pakis' and 'coloureds' similar to those which have probably taken place on these street corners for centuries, but rarely with such zeal. The only refuge is a church - and it's an ancient and peaceful one too. All Saints stands as a sort of traffic island, surrounded by the lowest-budget hotels and guest houses I can imagine. The churchyard is a puddle of mud, as an ill-conceived extension is being build in a quesy, 21st century ecclesiastical style. The long, gabled walkway to the main door is closed off and I'm forced to circumnavigate the building, taking in it's charmingly mossy older sections which are bolted unceremoniously onto Victorian alterations. During my circling I spot - and deviate to photograph - an abandoned pub - The Angel. Oddly complicated with a small tower and spire, and with the bold remains of a painted gable advertising port for 3/- a bottle, it's a shame to see it in decrepitude. Returning to All Saints via the eastern gateway, I hoped to gain entrance, but today the church was off-limits. I found a bench in Stratford Park and rested for a while, finally digging into the supplies I'd purchased in Poplar, which felt like a world away.

The final section of my walk took on the desperate rush which often descends on these jaunts in the afternoon. An awareness of time, of the limitations of my own tired body and of the sense that I'm still in unfamiliar surroundings which pushes me to head for safe ground. This time, it wasn't far away - and there was still time for a brief detour along the route to familiar surroundings. Edging into the centre of Stratford, I tried for coffee but gave up at the sight of the queues. In defiance of all the doomsayers, the Stratford Centre remains bustling despite Westfield towering beside it. The shabby, unpredictable shopping centre remains a magnet for the locals while the tube brings outsiders into the shinier, newer buildings just feet away. I explored a little, finding Joan Bakewell's Theatre Royal snuggled in between new buildings and curving access ramps. The bright, blood red frontage is a reminder of yet another different East End, nestled against the new. Unable to face the crowds of Westfield, I skirted the station and zigzagged along Angel Lane, over the railway and into the strange interface between Leyton and the Olympic Park. My aim here was to walk through the former Athlete's Village, now emerging as a new suburb. Access was via Penny Brookes Lane - a long, straight road which divides Westfield from the unimaginatively dubbed "East Village", coming to an end on Celebration Avenue. Aside from the contrived street names and the eastern bloc architecture, the place doesn't feel entirely artificial. It is incomplete and unresolved of course - the ground floor of each block gaudily advertises the space inside and how it could be used. Some of them show promise - "reserved for dry cleaner" or "let to wine merchant" - but most are as yet empty. Above though, many of the windows show signs of life - bicycles on balconies, washing hanging. Trains rumble close by, under the earth. Just like Leamouth and Canning Town though, there are few people around. I cut through a pleasant urban park - just beginning to lose it's 'planned' feeling - and cross into the Wetlands Walk part of the park. noting that even now a security guard is directing people walking along Olympic Avenue. The wetlands are interesting and peaceful, populated by water birds unconcerned with the manufactured nature of the habitat. The pathways through the park however are sealed off - not for security now, rather to see work done to rationalise the huge bridges into a more reasonable post-games walkway. I ascend to cross the River and head down to the towpath. This is possibly the last section of the Lower Lea I've not walked - the tantalising gap between where I left my last walk and the Eastway. Glimpsed longingly from the road many times, but always out of reach until now. I savoured the walk, taking in the sweep of the park and the Velodrome glowing in low sunshine beside the permanent Olympic Rings.

In a sense, this completed a ten-year long excursion through this part of the city. The sense of completion wasn't lost as I slogged the last few steps to the bus stop on Ruckholt Road, and made my way back to contemplate the walk over coffee in a familiar station haunt. My pattern of exploration here has followed a method - albeit unintentionally - over the years. The railway is the advance party - and I'll strike out through new territory first in the safety of a train - but then, slowly but surely I'll edge out on foot, covering the terrain in detail. Today's walk marked both a new eastern frontier, and the end of a long-standing exploration of what lay within it. As ever though, the very act of walking and choosing a path suggested future walks in the turnings I couldn't take. I can only hope it won't be long before I can take those paths too.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

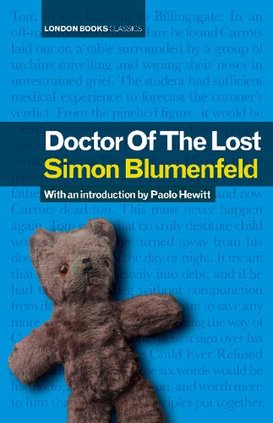

By the time Simon Blumenfeld's writing career had begun, the East End he writes of in this - his final novel under his own name - had all but disappeared. In fact, this potted life story of Thomas Barnardo documents some of the changes which Blumenfeld would have seen himself, being born a son of Sicillian Jewish immigrants in Whitechapel. Through the eyes of his Barnardo character, Blumenfeld surveys the East End at the end of the 19th century, taking in its squalor and injustice and balancing it with the now familiar tropes of character and spirit to portray what must have seemed an impenetrable horror to the deeply religious Dublin medical student on his arrival in Stepney. It would be easy to characterise this as an opportunity for Blumenfeld to advance his communist views, but there is a tension here - while Barnardo wishes to see "No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission" and is seemingly unconcerned with the underlying political and social injustice, he regularly debates this with Haddock - "The Black Doctor" who sees no hope without societal change.

Taking it's factual cues from historical and the public records of the remarkable Barnardo, the novel fills the gaps with surprisingly effective supposition and dramatisation. Barnardo himself is sometimes unsympathetically devout, but bristles with energy and indignation too. Filled out with engaging characters drawn from his real experiences in the East End, the sharply drawn dialogue and edgy cockney wit which Blumenfeld deployed in the earlier, more controversial "Jew Boy" return. The scenes in pub and music hall resound with a reality which stems from first hand experience - as Blumenfeld was for over thirty years a writer for The Stage, in fact attaining the official record as the "oldest living columnist" during his time there. Topographically, the novel is tightly secured into the triangle of Stepney, Mile End and Limehouse - areas Blumenfeld would know well, and from which he draws rich descriptions of places, some now changed immeasurably. When the novel does stray out of this liminal zone it is a little more fanciful and blurred, echoing the strangeness of wealthy London to those who lived their entire lives in the East, and equally the horror and disbelief the upper classes felt looking in from outside.

"Doctor of the Lost" tells a fair approximation of the sometimes forgotten life of the man behind the charitable juggernaut which now has a global reach. As a novel though, it works better - with many passages of wonderfully crafted descriptive work which provide Blumenfeld with the opportunity to explore his territory in the East End. It would be terribly easy to enter a debate about how much of it is truth - but the saddest truth is that the need for a Barnardo ever arose in Victorian London.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.