By the time Simon Blumenfeld's writing career had begun, the East End he writes of in this - his final novel under his own name - had all but disappeared. In fact, this potted life story of Thomas Barnardo documents some of the changes which Blumenfeld would have seen himself, being born a son of Sicillian Jewish immigrants in Whitechapel. Through the eyes of his Barnardo character, Blumenfeld surveys the East End at the end of the 19th century, taking in its squalor and injustice and balancing it with the now familiar tropes of character and spirit to portray what must have seemed an impenetrable horror to the deeply religious Dublin medical student on his arrival in Stepney. It would be easy to characterise this as an opportunity for Blumenfeld to advance his communist views, but there is a tension here - while Barnardo wishes to see "No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission" and is seemingly unconcerned with the underlying political and social injustice, he regularly debates this with Haddock - "The Black Doctor" who sees no hope without societal change.

Taking it's factual cues from historical and the public records of the remarkable Barnardo, the novel fills the gaps with surprisingly effective supposition and dramatisation. Barnardo himself is sometimes unsympathetically devout, but bristles with energy and indignation too. Filled out with engaging characters drawn from his real experiences in the East End, the sharply drawn dialogue and edgy cockney wit which Blumenfeld deployed in the earlier, more controversial "Jew Boy" return. The scenes in pub and music hall resound with a reality which stems from first hand experience - as Blumenfeld was for over thirty years a writer for The Stage, in fact attaining the official record as the "oldest living columnist" during his time there. Topographically, the novel is tightly secured into the triangle of Stepney, Mile End and Limehouse - areas Blumenfeld would know well, and from which he draws rich descriptions of places, some now changed immeasurably. When the novel does stray out of this liminal zone it is a little more fanciful and blurred, echoing the strangeness of wealthy London to those who lived their entire lives in the East, and equally the horror and disbelief the upper classes felt looking in from outside.

"Doctor of the Lost" tells a fair approximation of the sometimes forgotten life of the man behind the charitable juggernaut which now has a global reach. As a novel though, it works better - with many passages of wonderfully crafted descriptive work which provide Blumenfeld with the opportunity to explore his territory in the East End. It would be terribly easy to enter a debate about how much of it is truth - but the saddest truth is that the need for a Barnardo ever arose in Victorian London.

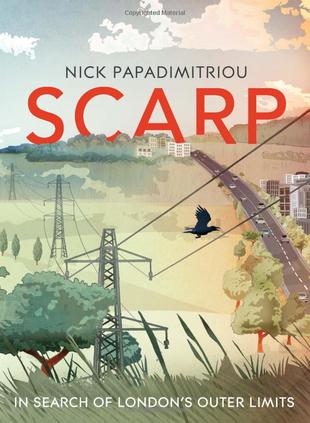

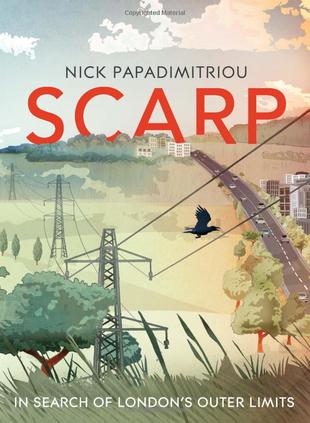

It's a long time since I felt the need to write about a book I'd read on here, at least as directly as this - but perhaps it's something I should do more often. The irony of reading "Scarp" in the middle of Glasgow, while the city moved quickly to take advantage of unexpected sunshine wasn't lost on me. George Square glistened in the light, pale skinned, blinking office workers emerging for their lunch break. Spending it with trouser legs and skirts rolled up, shades on while feet away, propped against a huge marble monument and just a little way from the huge metallic Olympic symbol erected for the summer, I sat devouring this curious book. In some ways, it's the book I wish I could write - part personal reverie, part hymn to the places around me. It delves deep into the landscape, and where current descriptions won't suffice creates a new map - you won't find "Scarp" identified anywhere I'm certain. But that's where this book plays its master stroke - we all invent our own maps and landscapes, but some of us do so more consciously than others. So "Scarp" is Papadimitriou's name for a mass of high-seated land which joins Chiltern Ridge to Lea Valley in a broad sweep across his beloved Middlesex. Buried in it are streams, lanes and byways which he has walked - often in dark times with all the associations they carry - to make sense of his county and his world.

Papadimitriou describes his work as deep topography and sets himself a little apart from the Psychogeographer. I was sceptical about the need to do so at first, but now I think I accept it a little more. He takes a sort of amalgam of old Ordnance Survey atlas, decommissioned guide book prose and personal recollection, and rewalks the landscape with no preconception. He accepts its stories, often it's casualties without judgement and most importantly without recourse to human sciences or politics to justify the links he makes. The prose is sometimes edgy, fast-paced and visceral - but is equally prone to longer passages of lush descriptive work - not least when Papadimitriou strays from a well-worn personal path and finds a new vista just feet from his more routine walks. The thrill of this is palpable in his writing, and having felt this same heart-leap at a sudden turn of a corner and never quite expressed it, it gave me huge pleasure to see it described in print.

Ultimately, "Scarp" is unresolved. We never get the end of the autobiographical thread which winds through the book, explaining perhaps why the author took to the edgelands and the streambeds - nor do we get to achieve the idea of "Scarp" as a whole. But that's because Papadimitriou hasn't yet managed that either. And it's likely he never will. There is both a luxury and a a risk in writing about such a specific and rarely trodden area. The post-cultural tourists who follow in the footsteps of the more famous psychogeographers probably won't stray this far up the Piccadilly Line, and this is perhaps a bit too redolent of the pylon, sewer outfall and business park to get the semi-professional walking set interested. But "Scarp" is a life's work, a labour of intense love for the landscape and a tribute to the land which sustains us, which we walk in difficult times, which links up homes, prisons, hospitals and bus stops. This is the landscape challenged and personified, but described in the loving detail of a botanist's catalogue. It's nothing short of a remarkable piece of work in that respect.

After a bewildering day, and with a painful eye infection I set off straight from work on a packed and sweaty train to Bath. The reason - a chance to see the Peter Hall Company performance of 'Waiting for Godot' at the Theatre Royal. Four friends in tow too - with varying expectations and ideas of what they were about to see, which was even more fun - what would they think?

I've wanted to see a performance of Godot for some time, having only previously seen a filmed version. This 50th Anniversary performance seemed an ideal time . I wasn't disappointed. It always seems that the play is treated with reverence and I've heard tales of some terribly serious productions, but the cast managed to find the space to enjoy themselves. They picked up the playful thread which Beckett wound through the work, running with it and engaging the audience. This exhuberance made the truly harrowing parts - particularly in Act II - by contract far more powerful. Jack Lawrence as 'The Boy' reminded me what a strange and sinister presence this character is in the play.

I'm no authority on theatre, but this was an enjoyable production of a favourite play. The audience generally seemed to agree. Polling my cohorts afterwards, most of them enjoyed it too. One or two of us talked at some length about the play trying to decide if it was 'depressing'.

A few pints of Pitchfork at the Old Green Tree convinced me it wasn't.

Spent some time chatting to a friend I haven't spoken to for some time tonight. Strangely, during my period of near obession with B S Johnson she had selected a couple of quotes found in a Guardian review of Like a Fiery Elephant for a homemade bookmark. I know I'm probably a predictable bandwagon-jumper in some respects but I found it odd, especially as we usually have such different tastes.

Got chatting about bookish matters, and particularly the possibilities of both of us having small things published soon. Thought how strange it would be to see each other's work in print rather than on a computer screen prefixed by the message "What do you think of this then?".

A big stack of books has once again developed following the Literary London conference - including Ford Madox Ford, Patrick Hamilton, Woolf and Sterne. Where the time will come from between reading items on Management Theory, I have no idea.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.