Throwing A Dead Rat At The Curtains: A Prelude To Flight

Posted in London on Tuesday 1st April 2014 at 9:04pm

Today we headed east, in order to travel west. The trip to Heathrow has been a fraught one in the past - either a prelude to separation, or a nervous weather-beaten dash to meet up. In either case, it has been a strange and sometimes painful excursion. This time, we wanted to make sure it was going to feel different. It was the beginning of a new era of travel for us after all... It began, ominously though, with a call downstairs. One of our angelic and innocent kittens was petting at her first kill - a baby Water Rat which had strayed from one of the Rhynes nearby no doubt. With a surprising turn of violence, she lifted the bedraggled item and hurled it a the curtains. Our trip was blessed with a sacrifice it seemed.

We set out around noon, heading for the station in a burst of sunshine. Standing with our luggage at Worle Station, it seemed improbable that we could pull this off. The train to Bristol provided entertainment in the form of an attempted fare-dodger scuppered by travelling Revenue Protection Officers. He told them he was "a very busy man!" but it didn't wash. We grabbed a leisurely drink at Temple Meads before changing to our London train. Amazingly, given First Great Western's recent record, things went smoothly and we were soon creeping under the roof of Paddington station on a surprisingly springlike afternoon. Our first stop was souvenir hunting for people we'd be meeting overseas - Paddington Bear and London related items purchased, we headed for our hotel to integrate them into our luggage.

We'd thought about a trip to Harrods for some time, and the need to pick up some small but classy things as gifts gave us the perfect opportunity. Given the pleasant afternoon we decided to walk through Hyde Park, passing the Long Water and the Serpentine, with the Albert Memorial shimmering through the haze. Thus we echoed the hidden route of the Tyburn Brook - another lost river, and another entry point into the story for me. The park was busy with Londoners surprised by the sun. A girl clad in hipster velvet rolled up her skirt to get her pale knees tanned, and the Diana Memorial Fountain was busy with paddling children and lounging tourists. The haze was in part a product of the Saharan Dust Cloud, whipped up in North Africa and deposited on us by a warm current of air. It promised terrible issues for some in coming days, but for now though it leant an unreal shimmer to the park, blooming with the new Spring.

We walked along the edge of the park, diving in between some Mews to reach Knightsbridge. Harrods loomed suddenly between the buildings, inducing a gasp of surprise at its scale. Before we headed in, we stopped into a gushingly ornate Italian place for an early dinner. Watching the world go by outdoors, we contemplated our trip and its complexities. Just now, it was all possibility and potential. Things felt uncommonly good. Eventually, we headed across the street. As ever, Harrods didn't disappoint - the Food Hall heaved with ludicrous temptations, harassed businessmen picking up 'something special' competing with tourists for space. We trailed through endless departments, few of which declared their prices openly. House music thudded in the fashion quarter, while the kitchenware area was marked by calm, bucolic music. Meanwhile in Bedding, a head-scarfed Arabian woman bounced on a bed and receieved a quote of "Four thousand, seven hundred" - though it wasn't clear if this was for the whole ensemble, or just the linen. Our last stop was the foot of the Egyptian Escalator. In itself, this is a highlight of the building - a period piece which documents the craze for all things Ancient in the early 20th century - but the bizarre and gauche memorial to Diana and Dodi placed by Mohammed Al Fayed is like a magnet. It's impossible to ignore the terrible statue, while puzzling over the weirdly masonic 'pyramid and hourglass' device under the soft-focus icons of the tragic pair. We took surreptitious pictures before leaving it to the tourists.

A taxi ride back through the park in a hazy sunset completed our excursion for the day. The driver navigated us into Bayswater and the knotted streets of stucco-clad hotels, and we settled in for the evening. Tomorrow would be more hectic, but just for now London was strangely homely and comfortable territory.

View Hyde Park Walk in a larger map

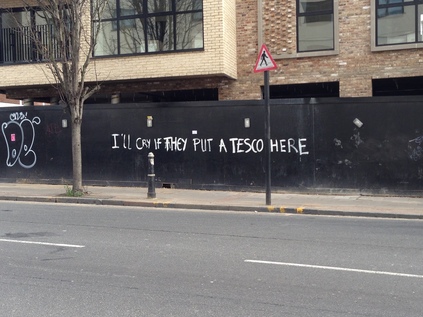

It feels like a long time since I've done this...as the train edges into Paddington, with a defiantly strong sun burning off the misty morning cloud layer, I'm strangely nervous to be back here. It's impossible not to remember the first, tentative arrival all those years ago as the power car comes to rest a few feet from the buffer stops, and there is a mad rush for the ticket gate. Life has been busy lately - and travel plans have focused on a trip west in a few weeks time - so we've spent time at home, making a home in fact. This escape feels precious and rare, but at the same time the sense of familiarity is welcome. It seems impossible to tire of London, just like the saying goes. Our first destination though, is entirely indulgent... We start on a 205 arcing around the edge of the City. The sun is up in earnest now, and the yellow brick is springing into life. The glass facade of the new University College Hospital building reflects a view of the bus back at us as we creep along the Euston Road. The confusion of Crossrail work around Moorgate diverts the bus into unexpected territory - the grim fringe of Shoreditch along Great Eastern Road giving way to the more chic side of shabby as we emerge from Holywell Lane and head for Liverpool Street. From here a grimy windowed train takes us the short hop to Cambridge Heath station where we emerge into a sun-baked Mare Street, turning to head along the Regent's Canal towards Broadway Market. Why did we take this convoluted detour on a day dedicated to being tourists? Simple... Coffee.

30 St. Mary Axe

|

Leadenhall Building

|

Anyone who has read this sorry screed of travel details will know this is not a new part of the world to me. But, I'm almost ashamed to say I've never been inside the precincts of the tower. Today we ventured in - undeterred by the rude security staff and the high prices for audio guides, we shuffled along the cobbbled streets to Traitor's Gate. The White Tower glittered beside us, as we turned into the courtyard around the Wakefield Tower and admired the view. An accretion of architectural styles and periods, a building extended and refortified with passing years and growing threats. It felt like the foundation of modern empire: a continual shoring up of tradition with more and more martial superiority. Having watched a guard-changing ceremony while Raven's picked at unsuspecting tourists' picnics, we joined a crowd heading for the Crown Jewels. At last I'd see some of the fundamental tools of monarchy for real. We worked our way around the rather cleverly staged display, watching projections of coronations, and marvelling at the perfectly preserved artefacts. Of course the really old things were gone - destroyed by Cromwell in the revolution - but here were tokens of Carolingean splendour, designed to shamelessly announce the reinstatement of monarchy. At the key moment, as we passed the state crowns, orbs and sceptres we stepped onto a conveyor which slowly edged us by at a reasonable speed. Like some sort of gameshow with impossible prizes, we guessed the value of the Cullinan II diamond, and found ourselves out by the order of hundreds of millions. Blinking in the sunshine again, we sat awhile and appraised the situation outside the tiny, sequestered church of St. Peter Ad Vincula. Overwhelmed by royalty and the sense of enclosure we decided to head for the river.

The sunshine had brought the crowds here too, and we queued for so long beside the pier it seemed we'd quite literally miss the boat - but we made it comfortable, the crowds still lining up to board the vessel while we found a seat among a group of disinterested Spanish tourists. We finally set off, curving out into the Thames, before turning and setting off upstream with Tower Bridge and the exterior of Traitor's Gate receding behind us. Under London Bridge, and then to Blackfriars, where the Fleet was concealed today - with a Thames Waterman providing commentary along the way. Edging around the bend in the stream we left the City of London and moved along the Embankment towards Westminter Pier. The journey was all too short - a quiet, relaxing interlude before emerging again into a press of tourists around the Palace of Westminster. We made our way carefully around the confusion of pedestrian crossings at Parliament Square, looking for a good angle on St. Stephen's Tower, but continually finding ourselves thwarted by the low, early spring sun. It was chilly now, but still bright and we decided to walk along Whitehall, past the Cenotaph and the fortress-like gates of Downing Street and to Trafalgar Square where we could board a bus back to Paddington.

As we sipped champagne in a spot which has become a bit of a landmark to us, we reflected on the trip ahead of our train home. It had been a long, tiring and fulfilling day - a return to London after a period of absence longer than I can remember for a good many years. Once again, as life changes, so does my relationship with the city. I never thought I'd be a tourist in the traditional sense again - and certainly never thought I'd enjoy it so much. The memory of the boat bringing us west via the curving silver arc of river sparked an urge to be back again soon. There is an entire new park to explore out east, and many more of these tourist adventures ahead...

View Hackney, City & Tower Walk in a larger map

Throughout my adult life I've encountered fairly little serious prejudice, for which I'm absolutely grateful. However there are a couple of low-grade issues which seem, oddly enough, to exercise people - my hatred of cheese and my lack of a driving license. Somehow these matters, when first learned by a new acquaintance and - as we all naturally do - projected on themselves, seem to incur a shudder of distress. Imagining life without parmesan and parking fines is, it seems, almost too much to contemplate for most. However, some people just can't leave it there and assume that this is some sort of handicap. Hopefully, the travels I've recounted here will dispel that. With some forethought and planning - which are never bad things anyway - there are few places I can't get to. That said, some places are just not easy at all... Yeovil. Clinging to the southeastern boundary of Somerset, and probably not more than forty miles from home. This little corner of my home county doesn't offer much in terms of attraction, and hasn't ever been much of a draw despite its official website proclaiming that its attractions could "fill several days of a holiday". Its probably been the same for much of the rest of the population over the years too - the road network doesn't facilitate easy journeys to that area, and the railway from Taunton was erased in the sweeping closures of the 1960s. Now it's either a painfully long swing around via Bristol and Bath on the train, or a multiple bus trip. Today, we had to head for Yeovil and I wasn't optimistic. After three solid weeks of torrential rain, the Somerset Levels are a glassy sea of water. As we arrived at Weston station, a further lashing of rain was being hurled at the metal roof. It didn't feel like a good sign. The aim was to mode-shift - first to Taunton by rail for speed and convenience, then to switch to bus to get into town and pick up a No.54 out to Yeovil. A long convoluted turn through central Somerset would follow, and we'd arrive in Yeovil just before the appointed hour of 10am. As we sheltered at Taunton station, it all felt tenuous and unlikely, and I began to get why people shuddered at my carless lifestyle. That said, they'd have been up just as early given traffic onto the M5, and wouldn't probably be much ahead of us right now. But of course they'd be warm, basking in the illusion of control and listening to....

Well, listening to Billy Joel if the coffee shop we stopped into was any guide. We sipped oddly acidic, weak beverages before heading back to the bus station and onto the bus which would take us to Yeovil via Langport, Somerton and Ilchester. Some of these towns were just names on a map, or timing points on the railway which no longer had stations. Having spent my early life poring over maps of Somerset, this was something of an adventure for me. We set off, and once we'd escaped the urban sprawl of Taunton and the motorway hugging Blackbrook business area, the true scale of the flooding became evident. The bus hoved into the middle of the carriageway to plough through churning lakes of uncertain depth which lay on the road. The fields around us were a silvery mirror of water, with distant church towers rising like lighthouses. I'd seen the Sedgemoor part of the levels like this of course, the tiny roads like causeways - but the lower levels were a broader, emptier sweep of land, and thus were breathtakingly strange to see like this.

The little towns we passed through were interesting and merited mental notes to come back. Langport saw us meet the road from Bridgwater not far from where the swollen River Parrett passed under the road. It was also our first encounter with the London to Taunton railway line which really ought to have stations in these growing, prosperous spots. We met it again at pretty Somerton, an ancient capital of the Kingdom of Wessex, all sandstone buildings and market town charm. Turning south we trailed the wide floodplain of the River Cary, denied an exit to the sea by the canalised King Sedgemoor Drain, it wreaked havoc here on the valley floor instead, spilling crazily into fields and moorland. Despite the stormy start, the day was shaping up to be bright and cold. The views across waterlogged fields stretched as far as the eye could see. Finally we crossed the mighty A303, swinging beneath us and aiming directly for Stonehenge and London, before curving through tiny Ilchester and into the gravity of Yeovil.

Not much had changed from my hazy memories of twenty-odd years back. The town is still approached by a series of roundabouts and a ring road which carves unpleasantly into the town itself, betraying the forlorn backs of shops and businesses to the visitor. Beyond that I didn't remember much - a family visit and one evening for a gig on Heavenly's 'Crap Towns' tour - hadn't left me with much material to work with. So arrival at The Borough, in the middle of a fine little street of shops was a pleasant surprise. St. John's church loomed, squat and yellow in the winter sun, and was surrounded by pleasant small stores and restaurants. The place bustled in a way I hadn't remembered. In fact, my memory was of racial disharmony - attacks on take-away owners - and of anti-social behaviour. I remember us standing in a small knot at the edge of that Heavenly gig, while the local youth went wild. Not to the music. Just because they did that all the time. It was hard to settle that with the first impression today. I headed to a recently opened branch of my favourite local coffee chain and settled in to eat, drink and read - the place thrummed with a pleasant energy and was never empty. I saw out a brief rainstorm and headed onto the High Street under a rainbow. The top of the hill echoed the first impression - good old buildings, used wisely by decent stores, with the ancient street layout defining the townscape. As I slogged down hill though, things changed. Firstly The Quedam.... My father and I would joke about this - our former local radio station, Orchard FM, would advertise this shopping centre four or more times every half-hour, with an absurdly optimistic recession-defying jingle. It was looking a little tired and betraying it's late-1980s heritage. The descending curve of a street parallel to the High Street was lined with a jumble of heritage bungalow storefronts. The haphazardness was carefully planned to resemble the shopping street this may once have been, the name appropriated from the town's Roman history. The Quedam was a sham - the side of the street which abutted the High Street was mainly a series of back entrances to the stores which had their main windows looking onto the established shopping thoroughfare. There were a fair number of empty units, and few folks around on a January Tuesday. At the end of The Quedam, there was a fork in the path - a turn onto the High Street to face a despairingly ugly 1970s block, with an impossibly large discount store at its foot - or a turn into Glover's Walk. This was an earlier experiment in shopping, and linked the town to it's bus station via a brief, tiled precinct. A favourite flourish of developers thirty or so years back. Now it was a gloomy, empty walkway lined by sorry looking market stalls. A promising but beleaguered craft store solidered on, and near the Bus Station The Gorge cafe was prosperous despite it's dated red vinyl and gloomy dark wood interior.

I retraced my steps to The Borough, marvelling at how many strata of retail developments could co-exist in such a small town. Here, where the historic town market would have assembled, it was hard to envisage how a walk down the hill would become more and more depressing. I sipped coffee, relaxed and waited by the 'phone for my escape route from the town. The bus, as it left, took us a circuit of the ring road, the service lanes to the shopping centres carving off into the knot of the Town Centre, the sun glinting off the roof of the pretty church. Yeovil is a part-charming, part-horrifying mess of a town. In some ways my former conceptions were challenged, and in others confirmed. It's hard to imagine a reason to come back here for almost the same amount of time - despite the curiosity of bus routes deeper into the hinterland and the interest of it's railway heritage. Well over ten years ago, I restarted my long campaign to travel every possible railway line with an attempt to avoid Yeovil entirely, an opportunity which will be repeated soon when the lines locally are closed. It's strange how I've always felt this way about the place, despite the changes I saw today.

I moved to Highbridge just little over eight years ago. It made sense for lots of reasons - I was living in a pretty unsatisfactory property elsewhere, and the family were all assembling here after a few difficult illnesses and a newly born child. We were coming together via an unspoken gravity which focused on my parents who lived away to the edge of the town in a quiet close near the Radio Station. My sister and her growing family overshot the southern boundary and ended up in the fringe hamlet of Alstone - a neat little family home with space to grow. But with my less pressing need for space and greater need for economy, I ended up here in the centre of things. Well, perhaps formerly the centre - because there are few businesses left on Church Street, save for hairdressers and take away food stores. My flat was perfect - a short walk to the station for my frequent escapes, a stone's throw from good beer at The Coopers Arms - it was just the bolthole I needed. In reality I'd spend little time here - edging around a triangle centred on home, supermarket and railway station on the whole, and making regular escapes to what many here would consider 'foreign parts' elsewhere in the country. But it wasn't possible to remain on the edge of the debates about the future of the town. Like always, I just had to get involved.

It's easy to be critical of Highbridge - alongside many hundreds of places across the country which haven't made an easy transition from their mid-twentieth century golden age to these more prosaic, straitened times. But in the case of Highbridge, its easy target status has set in train a descending spiral which feels almost impossible to stop. Industrial decline is a tough one to tackle in itself, but here successive waves of ill-planned development have bolted new problems onto the town while simultaneously stripping away its public infrastructure. Traditional industries - bricks, bacon, railway vehicles - have gone completely. Light industry is being pushed out of town by more lucrative housing plots, and the motorway hugging strip of vast aluminium distribution centres is big on space, but light on people. Where do people here go for work? Increasingly, they just don't. Highbridge tops the table in terms of unemployment and deprivation - serious statistics which are easily ignored in a world of numbers, but which here on the ground are self-evident in the faces of people sitting outside their homes in the middle of the day, watching the traffic thunder by. I've often asked myself why it ended up this way.

It's all too easy to be fatalistic too - and to suggest that the decline of towns like this is inevitable, and none of this can be remedied. However, there is a more self-evident reason in the case of Highbridge - and, while I know this will be controversial in some quarters, this has a lot to do with Burnham-on-Sea. Burnham is on the face of it a genteel, benign neighbour - a fading Victorian seaside spa which spans a stretch of muddy estuary but delights in big western skies and the views of a broad sweep of beautiful coastline from its windy esplanade. The secret here though, is that Burnham is dying too - just a lot slower than Highbridge. The Town Centre is seeing its retail core crumble away - not precipitated by de-industrialisation like Highbridge, but by apathy and inaction. Independent retailers turn into charity shops, which eventually close. The few national chains who are here offer a downgraded, second-string service. At 5 pm each day, the shutters come down abruptly - and for some shops, they never come up again. Business-folk spit inexplicable vitriol in the local press - blaming the internet, or the townsfolk for not caring - never looking to the economic reality or their own refusal to move from ancient business models. But as Burnham declines steadily and the Town and District Councils struggle to manage its retreat, they use Highbridge as a defence mechanism - an urban buffer zone that can absorb the mandated social housing and the necessary evils of badly planned supermarkets. There has always been a grim-faced bitterness about this here in the Town: "Highbridge is a dumping ground for people they don't want." It's not entirely untrue - it used to be an expression of hugely exaggerated class prejudice, but now it's just chillingly accurate demography. Interestingly, voicing this particular gripe - even when it perhaps wasn't entirely the case - opened the door for policy and practice to completely make it so. It became a self-fulfilling prophecy, and the policymakers must have cocked a surprised eyebrow at just how easy it was in the end. It's almost like some people here in Highbridge wanted this to be the case perhaps?

Urban Planning is an arcane art, and its exponents go largely without thanks for what appears on the surface at least, to be a boring, clerical function. Done well, of course, planning shouldn't feel obvious - but here it has become a weirdly public activity that excites unhealthy interest. In short, Highbridge is in thrall to two or three major developer/land-owners who vie for a finite amount of public funding. They do so by buying cheap brownfield land and proposing schemes that offer tenuous and untestable benefits in the future. They put planners in the impossible position of trying to anticipate future moves - a game of chess for which the prize is jam tomorrow. Of course, these schemes are always just beyond the electoral horizon too - so approving them holds no immediate fear for the politicians in most cases either. So, if you believe any one of these visions, we're due a marina, a cultural zone, a rejuvenated retail area. But the truth is that any crumbs that our largely indifferent District and County Councils might drop here have been theoretically spent over and over again. The Councils are complicit in these games too, buying ransom strips of land on silted riverbanks, knowing that if the grand schemes materialise their tiny investments will sit squarely where someone else needs to build. But just like chess players, no-one needs to make their move hastily. It can wait. Highbridge will still be there and will be a little more desperate the longer the horizon is pushed out. This stalemate is played out behind Olympic-blue fences, in burned-out hotel plots and in strips of scrubby land in otherwise developed parts of the town. Planning here isn't a distant and administrative process at all - you can see and feel it slowly eating away at the place.

Of course, the only defence is to object - and some in Highbridge do, often very loudly and with the support of some dedicated, informed local voices. But resistance in Highbridge is tribal and patchy - not nearly as slick and well-managed as the middle-class retirees of Burnham pull off again and again. Groups form here, and swiftly crash as a few dominant and depressingly resigned personalities bring them down. Associations form around bids and funding grabs and swiftly retreat into their own little territory. There is no coherence, no sense of a town wanting to work together to get out of the doldrums. There was, many years ago, a bid to separate the Town Council into two. It fell, among dire warnings that Burnham was propping up Highbridge, and that we couldn't live without the guiding hands of our betters. These patriarchal, conservative (in its truest sense) attitudes from the Burnham centred Town and District Councillors are bucked by a few voices of reason here in Highbridge - but they're barely heard over the roar of organised, directed anger when similar issues crop up in Burnham. Take a tale of two formal applications - planning for a petrol station on a crowded, ill-planned supermarket site in Highbridge, and licensing for a Convenience Store in Burnham Town Centre. Both raise serious traffic and environmental issues, both will impact other businesses in the area. The first is supported - it'll increase competition for fuel prices and the noise and traffic won't hurt too much. The other is contested vehemently - it'll increase competition on local businesses and the traffic will be unbearable. I'm fairly sure I know how this will pan out - and recent decisions about the Tucker's Garage site, which isn't so different to the Highbridge Hotel in some ways, go further to prove how skewed the decision-making is across the two towns.

I can't leave this rant without at least some glimmer of hope, can I? There's always a little bit of light at the end of the tunnel, surely? Well - as it stands, no there simply isn't. While national policy turns the screws ever tighter on many of the people who make up the town's population, and while regional and local policy fails to recognise that it has taken all it can from the town, things are spinning out of control here on the ground. So what can be done?

- Well, firstly you need to choose your battles - there's almost no mileage in playing these issues out on a local website which is fast developing the journalistic morals of the Daily Mail and which has such an ill-governed and poisonous forum that it gets used to victimise people in real life, outside the online world of councillors with alter-egos and multiple personalities. It can't end well, drains the life out of those who indulge, and doesn't persuade anyone away from their strongly held opinions. I know it seems odd for me to suggest turning away from the internet, having been an early adopter and a regular exponent in the past. But there are many, far better ways of using social media to make a case for change than tussling with these people - who are never who they seem and represent such a tiny sliver of the people who are affected by these issues.

- Secondly, organise yourselves - and stay organised. Let the people who are able and skilled take the helm rather than the same old suspects with their loud, miserable voices and their defeatist from the outset stance. Get younger people involved - find out their aspirations for the town - put them forward to counter the image of Highbridge which persists. Don't use organisations solely to chase funds from the very bodies who are ruining the town. Raise your own money, achieve some independence from the broken political structure here. Keep organised by tackling positive things as well as fighting negative ones - even though the latter garners more support, it's momentarily hot and fast-burning. Play the longer game. The Dreamscheme is a fantastic example of this.

- Thirdly, you need to take your tactics to the next level. Find a public-spirited law firm that will work pro bono and tackle some of these wrong-headed decisions where they belong - with a higher authority. It's because councillors and developers alike know very well that Highbridge can't get organised or respond coherently that they continue to ride rough-shod over the wishes of the population. They're banking on no-one ever-challenging beyond a moan at a meeting or a post on an internet forum. Sadly, that is about as far as they go. It can be messy and expensive to go to court, and it's a ton of work - but it can and does work well. There are firms that want to be known for doing this kind of work, and bright, fresh-minded lawyers who want to challenge this activity. Find them and work with them!

- Finally, use your votes very wisely. Voting on party lines is something I've never advocated at the local level - but somehow, Highbridge needs to get representation on the ruling group at Town and District level. Failing that, strong independent voices are needed. But the traditional politics of Highbridge just perpetuate the issues. The greater enemy though is apathy. Chatting to the bored poll clerks over a series of elections, I've watched them move from a position of "Easy money, this!" to "Why did I bother turning up?" This is a national problem, but it's far, far worse here.

None of this is easy - and perhaps writing it down in this way is a little glib and self-serving? Maybe so. But I can't leave this place without hoping that somehow people will find their voices, form their opposition and fight their battles. I tried for my part, and didn't get very far - but there are brighter and more dedicated people than me in Highbridge for sure. Good luck everyone, and don't let the developers win!

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.