A Solid Mass of Heaven: A Weekend in The Borderlands

Posted in Travel on Sunday 31st March 2019 at 9:03pm

The drive into Wales was fractious and slow. The motorway was mired in congestion and overwhelmed with traffic, so we slalomed across the map heading steadily westwards on a successively narrower corridor of minor roads, a routing which made me - the navigator - distinctly unpopular for a while. Skirting major towns and curving along wooded channels, there wasn't much of a view beyond the monotony of a white line and the the threat of oncoming traffic. Finally, the valley opened before us: Hay Bluff glowered over the scene from the south, while our road briefly skirted the little town of Hay-on-Wye before heading into the countryside again. By a series of lucky turns and informed guesses we made our way to Glasbury-on-Wye and The Grange - the quiet bolthole we'd found for the weekend. It was good to get away - life had felt pressured and a little off-kilter these past few weeks. We were adjusting to new routines and new challenges, while integrating the same old pressures and stresses into a world where we both worked for the same employer. Escape felt well-earned and rare, and the fine old farm house with its casually friendly hostess and loping guardian hounds who were far too friendly to truly defend the place. We were instantly comfortable here, and celebrated by escaping to the local hostelry for too much food and wine. It was good to be in the Borderlands.

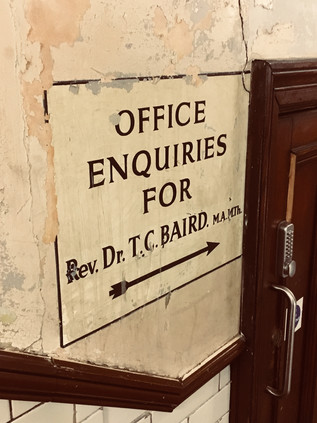

But this trip was also about exploring, and I was out early the next morning to make the walk beyond the pub and into the tiny hamlet of Glasbury. At the meeting of roads near the gateway to the common, I found a familiar sign: 'London Borough of Redbridge'. Oddly out of place here, the distinctive emblem and bold, plain design struck me first. I was transported to distant walks, connected strangely back to my wandering in the capital. Since 1963, the borough had sent groups of students - sometimes up to 1800 each year - to Glasbury to experience the outdoors and particularly the opportunity to canoe on the Wye. The future of the centre was first threatened in 2011 when subsidies fell, and it finally closed its doors in 2015 with the Borough seeking a £1 million receipt for the property against a challenging savings target. The building stands, decaying and apparently unsold while the signs still show the anomalous ownership. Instead of the fast-running Wye, the young people of Redbridge will be encouraged to enjoy the comparatively local Fairlop Waters instead. Having walked their edges recently, I can testify to the impressive sweep of the park and the windy lakes certainly looked well-used by boaters. But were they a substitute for the adventure of a journey out here? It was sad to think of this decades-old trip to the mysterious valleys no longer taking place.

The Wye is broad and shallow at Glasbury, and I crossed the gravelled strand which led to its banks under the shadow of the road bridge. The river had scoured deep holes near the piers of the bridge which formed deep, dangerous pools requiring care in navigating a route under the carriageway. North of the bridge the river curved gently eastwards towards Hay, dividing into multiple streams and rejoining, and later we would set out in the same direction. My last visit to Hay was lost in a haze of confused sixth-form memories. We were brought here to experience the 'town of books' and to delight in the ramshackle cottage industry which presented its charming face in the old town. I didn't quite appreciate the rather ragged, hand-to-mouth existence of bookdealers then. Even these comparatively well-to-do country types existed in a world of unlikely fellowship and bitter competition. We'd get to see that a little on our excursion: enquiries after Beat Poetry in the wrong store incurred wrathful spitting of another bookseller's name. Try him. He likes that sort of stuff. We'd duly shuffle on, each with only a few pounds to spend on wretchedly ill-used paperbacks, hustled away from the glass-fronted cases containing the really good stuff. Don't even look. That's not for you. We scaled precarious spiral stairs to look an unsorted stacks of remaindered novels, and clattered into dank basements full of songbooks and sheet-music. It was both wonderfully educating and deeply depressing. I've struggled with second-hand shops ever since. Not until a visit to Powells in Portland years later would I even dare to seek out authors I cared to find works by, always feeling so utterly deflated by the sheer volume of pulped print around me. This trip was also one of the few times I got into any real trouble at school... On a brief stop in Cheltenham on route to Hay I'd strayed into Our Price records, and came away with a 12" single of 'Fishes Eyes' by New Fast Automatic Daffodils using virtually all of my spare cash. Later, we were ushered by our English teacher into a queue under a damp marquee, each of us duly bound to line up, purchase a book of poems and have it signed by D. J. Enright. Enright was virtually unknown to me then, aside from being the editorial credit on a number of anthologies. From what I'd seen of his work he didn't belong in my naïve, resolutely teenage canon. We shuffled forward, the better-prepared clutching their Collected Poems while the more thrifty held slimmer volumes. The author, heavy browed and bowed with age and likely boredom, smiled generously and signed almost unintelligibly. I assumed poets must all have terrible handwriting. I realised at some point in this slow procession towards Enright that I had neither book nor the funds to purchase one. I clutched the signature red 'Our Price' bag conspicuously, wondering how to play this? Despite my haughty assumptions, Enright was truly an impressive figure: I didn't know of his long sojourn overseas and the near international incident he'd caused in Singapore, I didn't know of his loose but important association with 'The Movement' and that last gasp of an older school of serious British writing. All I knew was that my literary pretensions lay elsewhere, and that my wallet was empty. I shuffled in front of the author in my turn. He smiled benignly as I offered him the New Fast Automatic Daffodils record. He examined it with a wry chuckle and said he'd not expected to see this. Eventually he took us his pen, scribbled something on the cover and handed it back with a gruff laugh before turning to the next in line. As I wandered away to inspect the record, I felt the eyes of my disgusted English teacher following me across the marquee. The inscription read:

I take no responsibility for the contentsD J Enright

I was suspended for three days as I recall.

Our day in Hay-on-Wye was very different: we found great coffee in the Old Electric Shop which combined café and retro furniture sales, strolled around the busy town and explored both a shop devoted to selling maps and the wool and food stalls in the restored Butter Market. The sun blazed over the town, and I decided that rather than return in the car I'd walk back to Glasbury along the river as far as I could. We parted at the top of town near the currently under re-construction flanks of Hay Castle, and I slipped into a store to buy a little vintage brooch which Natalie had admired earlier. before setting off for the river. Access to the river was down steep steps which turned back under the road bridge and onto the path of the former Hereford, Hay & Brecon Railway. The line had closed in 1962, leaving Hay at least twenty miles from a railway connection. Taken over by the Midland Railway, the route was joined a little to the north of the station by the Golden Valley Railway, heading east from Abergavenny and Pontrilas. The railway now was a broad, well-surfaced path running alongside a steep bank down to the River. It was quiet and cool here, just occasional walkers to distract me from my mission. The town was above me but could be miles away for all its intrusion into this calm, green cutting. In fact, I was passing out of town without realising - crossing the little Login Brook which trickled by the church of St. Mary the Virgin before reaching a tumbling confluence into the river below. Here I faced a choice: press on along the old trackbed, or head onto The Warren. I wanted to stick to the river, so I took the latter route, taking a broad sweep long the river bank where it curved around private meadows criss-crossed with unofficial paths. My presence, along with that of other groups of walkers and bathers was suffered if not sanctioned, and I followed the bank as far as I could, passing a busy weir where the already broad waters of the Wye scurried over stones. Eventually I was forced to head inland, and I soon realised there was little hope of getting back to river or railway. Instead I trudged alongside the busy road to Brecon, occasionally needing to edge along the dusty carriageway when the margins of the lane were impassible. It was challenging walking, and not what I'd hoped for, but the views were incredible - as was the chance to gaze down into the clear, angry waters of the Dulas Brook and Nant Ysgallen as I passed over bridges which I'd entirely missed when we travelled over them by car. As I neared Glasbury, I ascended a steep set of wooden steps onto the railway alignment, which cut into the lower foothills above me. The last mile or so of my walk should have been through a cool, wooded nature reserve - but a farmer, tired of walkers using it as a through route, had closed the end. I was forced to retrace my steps and to edge along the road yet again. I delivered the brooch proudly, a little dustier and more tired than I'd planned to be, but glad of the walk. We headed back into Hay later, to eat in a curious and rather secretive little restaurant and to drink a little more wine than I'd usually venture. I felt I'd earned the refreshment.

On our last morning, over an excellent breakfast, our host asked if we were going to travel home via the Gospel Pass. I knew we were close to Capel-y-Ffin and Llanthony, but hadn't hazarded a mention as I figured the drive would be very challenging on more, even narrower roads. These long-contested borderlands had featured in the confoundingly complex, dreamlike novel Landor's Tower by Iain Sinclair - and while I'd seen this as a minor distraction from his London writing at the time I first devoured it, I'd been haunted by the unseen landscapes and occult associations ever since. Surprisingly, the suggestion was eagerly accepted and after taking leave of the friendly dogs and the beautiful room we were soon heading off towards Llanigon, climbing slowly on a single track road. We saw very few other vehicles, a mist descending as we climbed towards the pass where England met Wales. The driving was exhilarating at times, the road hugging the edges of long drops into the valley below - and as we climbed we realised we we driving into a cross-country cycle race and needed to pause occasionally to let each cluster of cyclists pass unhindered. The road climbed towards the ridge and opened into a square of gravel which served as a carpark. We were surrounded by sheep, their eerie cries muffled in the foggy air. Lambs tottered along behind their mother, while groups clustered along troughs of feed. For a while it was just us and the sheep up here. The pass: Bwlch yr Efengyl, may derive its English name from one of two christian myths: that Caradog brought St. Paul through the mountains here to preach the faith to the heathen Celts, or that Crusaders passed by in the 12th Century preaching and raising funds for their expedition to the Holy Land. In either case, it has an ancient feel. The earth seemed to settle slowly when stepped on, the fog to part unwillingly to let us pass through. The sheep were unaffected, able to scamper and gambol along the mountainside at will. Humans though, were less welcome now. We pressed on, down the valley to pass the tiny church of Capel-y-Ffin - the Church of the Boundary - and to descend to the ruined priory at Llanthony. There had reputedly been a place of worship here since Dewi Sant established a cell in the 6th century. The first priory was established in 1108 via the finances of the de Lacy family and had become an important Augustinian house by the 12th century. However the priory faltered as attention turned to power struggles in the monarchy at the time of King Stephen, and the 4th Prior, William Wycombe took flight to Gloucester where he established Llanthony Secunda in the comparative safety of England. The de Lacy family once again took back the land and built the vast church which can be seen in part today, surviving despite the lawlessness and rebellion which stalked the borderlands and the rebellion of Owain Glyndŵr which threatened the Abbey's income and existence.

Llanthony continued to attract new groups of the idealistic and faithful, often with unlikely leaders. First came the troubled and hot-headed Bath born poet Walter Savage Landor, intent on improving the monastery but quickly falling into dispute with the locals who stole from him and failed to undertake the works he specified. His tendency to attack opponents in libellous verse saw him fall into further expensive and interminable conflict, and he finally left Llanthony for Jersey in 1814 at speed, reputedly having been flung from a first floor window by an unhappy local. Landor was followed by Joseph Leycester Lyne who arrived in 1869 making repeated attempts to buy the Abbey ruins from the Landors to prevent the operation of a public house in the grounds and to restore a religious order, based on his own strange take on Christianity. He finally admitted defeat and purchased 32 acres of land nearby to build a new monastery. Styling himself Father Ignatius, he established Llanthony Tertia where his eccentric collision of High Anglicanism and Celtic mysticism would ultimately fail to flourish. Diarist, clergyman and nudist Francis Kilvert observed that the guileless abbot was 'robbed blind' by tradesman he paid without a contract to finish the monastery, and Lyne fell foul of the Church authorities after publicising ghostly presences and visitations by the Virgin and reportedly being ordained as a Druid. It's perhaps easy to understand why Lyne would find this spot imbued with ancient power: the veil of modern life felt as transient as the mist here, and the idea that the old and new were entwined was strong. The Honddu valley slumbered unquiet under the dew and it was possible to imagine Lyne striding out, the hem of his robe damp, to meet figures which disappeared before he could speak with them. Nor was Lyne the last to attempt an understanding of this landscape, with sculptor and typographer Eric Gill setting up a somewhat notorious artistic community in Ignatius' unfinished monastery buildings. Gill's acolytes included the painter and modernist poet David Jones who drew on mythology and mysticism in his work, much to the cost of his reputation in the future when such things fell out of mode. Gill's reputation too has suffered from revelations about his personal life and proclivities - and there is a queasy realisation that his establishment of a commune at Capel-y-Ffin may have been as much about being away from the gaze of authority and polite society as any great artistic purpose. In both cases though, these men drew on the strange power of the little Honddu valley in their work. Gill left the valley in 1928, four years after arriving, reportedly troubled by its atmosphere, inaccessibility and great distance from London where many of his clients were located.

After exploring the ruins, we ventured into the tiny bar which still operates in the undercroft of the Prior's quarters. We were welcomed by a bluff and friendly man who spoke with the assuredness of a local, despite sporting a broad Mancunian accent. Delighting in the chance to tick Washington off the list of states he'd served visitors from, he talked a great deal about his association with the area and his return each spring to operate the pub over the busier summer months. He also talked about the range of celebrity visitors, including Jimmy Page who had called in while passing through the Ewyas Valley on route to recording commitments. The well-stocked little bar-room was accessed by precarious steps, and soon all attention focused on getting an elderly local safely to a seat nearby. We purchased a copy of the undated pamphlet by L D Fancourt which provided a brief history of Llanthony, skirting some of the more lascivious details of later occupants, and slipped away back to the car, to complete our journey. The road levelled, crossing and recrossing the busy Honddu as it rushed to join the River Monnow and eventually the Wye as it snaked towards the Severn. The arms of the valley slipped back, opening into a broad undulating plain surrounding The Skirrid or Ysgyryd Fawr, the shivering mountain which still experienced minor landslides but which was said to have partially collapsed in a lightning storm at the moment of Christ's crucifixion. Beneath it, the Skirrid Mountain Inn still did business - reputedly haunted by those hung at a local assizes which held session and dispensed justice here in an early sort of one-stop-shop arrangement, or by slain rebels from the time of Glyndŵr. Myth and mystery were never far from the surface here on the border, painted and written over and over: Jones, Gill, Eric Ravilious, John Piper and even Allen Ginsberg had passed through. With this surprising revelation my circle closed with an unexpected jolt, and I was the temperamental youth looking for Beat Poetry in the musty stacks of Hay bookshops once again.

As we climbed the silvery ramp of the Second Severn Crossing, I felt the unexpected weight of history slipping away from us. It had been wonderful to be back in Wales after a long absence thanks to its association with unwelcome appointments at the Home Office Immigration & Visa Centre. Now we could rewrite our own Welsh story, in a similar way to those who'd occupied the venerable and desolate valley through which we'd passed. It felt a little like our own pilgrim's road, and I was surprised how strongly I felt the curious pressure of time and place in the Borderlands. I scolded myself a little for letting my rationalism slip for a moment, but suspected that it was the natural rather than the supernatural which truly held sway in Ewyas. It had been a fine weekend and we'd found a special place to which we wanted to return. But the journey home had been surprising and enlightening. The valley still had more secrets to share.

You can find more pictures from the trip here. This post takes its title in part from Allen Ginsberg's poem 'Wales Visitation', you can watch him reading part of it to an unconvinced William F. Buckley Jr. below...

We are heading out to Germany for a few days to meet friends and see a little of Europe before it gets more complicated to do so. On some of the hottest days of an already warm World Cup summer, travel would present a number of challenges - but today, as ever it seems, French Air Traffic Controllers had decided to strike. The knock-on effects of this were minimal in many ways - a bit of a wait for take-off and a slightly irritated Captain - but there were benefits too... With slots over France in short supply, we took off on the eastern runway, heading directly over Central London and out along the estuary. Even at around 20,000 feet, the view was clear enough to see the city unfolding before me along the glimmering ribbon of the Thames. Seeing the territory I've walked and rewalked mapped out below was a rare and privileged sight for me.

As the contorted city river gave way to the broadening maw of the estuary I thought of the connection between the Thames and the Rhine, once a great river through a united continent which was soon to be artificially separated once again. Beneath me the Dartford Crossing signalled a passing into Kent, and soon the tiny towers of Reculver could be seen below. Beyond this, a sweep of blue showed the channels which boats eager sought between the off-shore wind farms and the ominous heads of the forts at Shivering Sands. Soon there was nothing but water, and then almost imperceptibly the countryside below was Belgium. It didn't look so hugely different from up here, but culturally and politically it could be a world away just now.

Despite heading into London by train on a fairly regular basis these days, I'm much less likely to find myself patrolling the network with anything like my former frequency. In particular, trips to points north are far less common and my familiarity with some places where I'd once have popped-up frequently has long since diminished. Some things though, never change - and so my first port of call on arriving at Bristol Temple Meads on the first leg of our journey to Manchester was the Customer Services desk. We'd been sold an empty promise - an 09:41 to Gloucester which simply didn't exist. The Filton Four-Tracking works were clearly going to cause us to have a long and fairly convoluted trip today - but I was surprised that it was going to be quite this tricky. As it happened, Great Western's staff sorted things swiftly by passing us on the 09:45 Crosscountry service to Birmingham New Street which took a long, lazy wander out to Swindon then reversed to amble up the Golden Valley Line via Kemble and Stroud before regaining its regular route at Standish Junction. At New Street of course we were left at the mercy of the Train Manager on the next service north - but a friendly and understanding railwayman let us travel in First Class for our troubles. I lazily dozed as we sped north on a route which I'd not travelled for a good few years. We arrived in Manchester a little late but relaxed and relieved to not have been too troubled by the awkward beginning to our trip. A swift tram ride through the busy city centre, basking in unusual bright sunshine, and we were at our hotel for the next two nights. It was good to be back.

Our last visit to Manchester had been on the hottest day of the summer, in a hotel which decided not to air-condition its upper floors. Predictably it hadn't created positive memories and much of the visit passed in a frustrating haze of heat. This weekend was predicted to be warm too but less intensely so, and we were able to get out and explore the city a little. During our stay I took my customary, early morning strolls and found myself approaching familiar streets from a different angle. All of my previous visits had focused on the narrow, north-south axis between Piccadilly and Victoria. This time I found myself crossing my own path and happening upon corners which I'd passed often but never turned. Manchester now, of course is a much changed city - vibrant, busy and cosmopolitan in comparison to my earliest visits. I negotiated the relatively recent Second City Crossing with some confusion, finding trams where I didn't expect them. Finally, and rather remarkably on the anniversary of the last time I stayed, I happened upon the Merchant's Hotel - a grim reminder that things had changed for me, if not for this forsaken hovel which was remarakbly still in business! On Sunday afternoon we wandered the Northern Quarter's busy market which I confess to finding a little dizzyingly busy, but the walk was rewarded with good coffee - first with indifferent service in Foundation Coffee and then in the much more welcoming Takk. We zig-zagged back to the hotel via Piccadilly Gardens, busy in the bright afternoon.

The main event though, and the reason for this trek up north, was the live My Favorite Murder. This has been a frequently heard podcast here for some time, and when tickets were announced earlier in the year, I knew I had to ensure they were secured! A VIP package meant some merchandise, priority entry and seating, and perhaps more nervewracking for both of us, a chance to meet Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark. I'm not great with celebrity - projecting my own thoughts onto them by imagining that they really just want us to leave them alone - but for others, it was the thrill of meeting people who've become heroes of a sort. Their irreverently funny but touching and sensitive forays into true crime have become a defence against homesickness - a little slice of the saner and calmer America delivered via the airwaves. We ate a swift dinner before heading to the Albert Hall - a former church turned concert hall which appeared to be crumbling from within, paint peeling and fixtures wobbling with little concern for modern health and safety rules. The bright sunshine illuminated the art-nouveau style stained glass from outside, giving the whole place a strange glow. While the performers found their 'daytime' show a little odd at first, the venue couldn't have been more perfect. I surveyed the crowd - predominantly female and a defiant mix of geeky types which it was a delight to be part of. I made conversation with a young gent sat next to me accompanying his girlfriend as a birthday gift. We speculated on the murders which might feature - what might be 'too soon' or 'too local' to land well. We played the reluctantly dragged spouses at first, but soon gave in to the admission we were looking forward to this too.

A couple of hours later we stumbled out into the dark of Peter Street, having met the perfectly delightful pair of presenters for a few short minutes. A little starstruck, still laughing at the show we stopped in for a beer before heading back to the hotel where yet again the ever declining Premier Inn brand let us down on customer service yet again. It wasn't going to spoil the day though - and consoled ourselves in knowing that the final night of our trip was being paid for by my talent for complaining. The next morning after a fine breakfast at Friska, a nearby eatery which appears to have made the leap from Bristol to Manchester, we headed for the station to cross the Pennines to York. On our last trip, a genuinely bizarre performance by the staff of Hotel Indigo had resulted in a full refund, an apology and an offer of dinner, bed and breakfast on the hotel in order that we could experience their normal level of service. The trip from Piccadilly brought back memories of long-ago excursions: craning my neck to see what was lurking on Guide Bridge Yard, secretly wishing I could stop off at the fine Station Buffet at Stalybridge and marvelling at the sudden burst into Yorkshire at the end of Standedge Tunnel. We soon found ourselves approaching York in wonderful sunshine, the station gleaming golden in the afternoon light. It was good to be back in a favourite spot.

After checking in - a much less irritating experience this time I'm glad to say - we headed out to catch up with friends at the York Tap. It was good to meet old friends and new, and to see some happy faces too. All too soon it was time to head back for our complimentary dinner. It was - well, better than last time - but still a long, drawn out and rather odd experience. As the restaurant closed around us while we waited for our dessert we speculated that this would probably have generated a complaint if we were paying. After this, we were a little wary of breakfast - but were greeted by one of the best spreads I've ever enjoyed at a hotel. The service was swift and friendly, and the food was frankly amazing. If we'd booked just the excellent room and this wonderful breakfast we'd probably have happily skipped the weird dinner experience. As we boarded the slightly overheated 10:45 back to Bristol I composed my response to the manager of the hotel. We'd had a much better time and a great welcome - but the restaurant was still strange and slow.

We stepped off the train into the usual mess of afternoon delays at Bristol, but feeling remarkably relaxed after the warm trip home. I've known for a long time that travel is good for me - but I'd underestimated how much I needed to escape on the rails like this. The next months - indeed the next week - will be busy and challenging. It's unusual to think of Manchester as an oasis of calm, but that's certainly what it's been for us this weekend.

The last few weeks of the year felt like a bit of an epic slog, and only the prospect of the long break we'd planned over the festive season kept things on an even keel. In recent times, we've fallen into a very pleasant pattern at this time of year - a quiet Christmas, a small gathering at home for New Year, then away on a road trip on the first day of the new year - a week when everyone else is unwillingly slogging back to work. It has worked remarkably well - hotels offer up rooms at ridiculously low rates in the post-festive slump, and if you don't mind short days and sometimes unpredictable weather, then it's a good time to be away - a brave attempt to stave off reality for another week perhaps?

Our trips also have a familiar pattern - up the west coast, the long straight arm of the M6 stretching into northern regions which still feel oddly exciting and wild to me, just like my earliest rail journeys along the remote and sometimes otherworldy main line. We pause on the journey north for a night - often somewhere in Lancashire - to maximise daylight driving, and to rest on what sometimes feels like an epic northern journey. This time our staging post was Liverpool - a city we've visited before, but this time we headed north out of the city in a sudden downpour, towards Stanley Dock. The grid of streets here hasn't seen much redevelopment - the sounds of the much diminished but still busy docks at Bootle shudder through the high walls which surround former smaller basins along the Mersey shore. The landscape is predominantly decaying industry with the occasional tile warehouse or shabby dockers' pub crumbling into the stones. Amidst all this is the Titanic Hotel - a vast, converted warehouse which squats on the northern edge of Stanley Dock. Inside the warm and spacious building a beautiful refurbishment built around the maritime history of the City had transformed the huge space into a comfortable and welcoming hotel. We were almost sorry to just be spending one night in the huge room with a view north across the docks to the mouth of the Mersey.

We set off in the morning and headed back onto the M6 for the journey north to Glasgow, breaking our trip at Abington where the flock of crows which has stalked the service area on two prior visits wasn't to be seen. We were staying for two nights - testament to the success of my gradual reintroduction to Glasgow following a despair-filled visit two years ago. Cruising into the city on the elevated carriageway of the M74 as it curved towards the Clyde, it was impossible not to feel lifted by a return to this place which has long served as a second, northern home to me. The glass towers sparkled in the damp afternoon and the trains shuttled along the bridge high above the river. It was good to be back, and after some confusing changes of room - handled impeccably by the hotel - we found ourselves in a wonderful spot overlooking the roof of Central Station, which reminded me of a visit long ago when the hotel was still a creaking, tired and menacing place with its long corridors stretching endlessly along the wings of the station. A return to Glasgow meant a chance to become tourists again, and we visited the People's Palace - a grave omission from my previous trips when I'd only stepped into the building to use the public facilities. The museum remains in the ownership of the city - an honest and frank appraisal of the rapid rise of the city and the problems that brought, and a celebration of the language, culture and political activism which are never far from any discussion of Glasgow. Afterwards we stepped into an old haunt, The 13th Note - but our quiet drink was disrupted by an ultimately harmless but persistent local who had turned up and seemed to be working the bar for a chat. His prodigious drunkeness though, lost it's charm and shortly after he was moved on - so did we. It was tough to leave the place again, especially in such strange circumstances.

Still repeating our itinerary from previous trips, we next headed through to Edinburgh using the finally completed M8 to swiftly cross from city to city. We'd changed our routine a little for this visit by staying in the New Town opposite North Bridge, with views over Waverley Station and the Castle to the south. It seemed a little strange to abandon the Grassmarket and not to experience the bracing climb up to the Royal Mile each morning, but the new location was a surprising win - affordable and decent accommodation which looked directly into the unattainable windows of The Balmoral across the street! A persistent rain set in a little after we arrived and stuck around for much of our stay - but it was still good to be back in Edinburgh. We headed out to our favourite restaurants and wandered Princes Street, along with a trip to the Scottish National Portrait Gallery housed in a remarkable building and home to a surprisingly varied collection. Edinburgh once again proved to be a relaxing and interesting spot, my old prejudices challenged once again by the city as it sparkled in a light dusting of snow spied from our window over Princes Street. It wasn't easy to leave at all.

Our final destination, after a long haul down the coast on the A1, was York - and again while a favourite location, a new prospect for our accomodation. However, it was to prove an odd and frustrating place. It's fair to say that Hotel Indigo's rooms were beautiful, but getting into the room was a painful process. A parking set-up that defied logic and seemed to require quantum physics to obtain a spot, followed by a check-in process operated by a corporate robot which had less charm and more inflexibility than an automatic check-in terminal was our introduction. The restaurant was even more of a challenge - the concept of Yorkshire Tapas essentially meaning that it was impossible to tell what was a main course, what was a starter and when the dishes would arrive. The staff, young and inexperienced, dashed from one calamity to the next - finally presenting me with a blank sheet of paper to sign when the till crashed.

And so our trip ended on something of an odd note - a fine week of travel, of old haunts revisited and new ones discovered - but with something of a flat last day dealing with the hotel. At the very least we came away with a stock of anecdotes, and the room was truly very comfortable. We've been exceptionally lucky on our trips so this is to be perhaps marked up as a minor irritation and an opportunity to vent on Tripadvisor. We head into the new year, and hopefully new travels, thankful for this all too brief interlude. For a few days at least, when I close my eyes to sleep I see the white lines of the road stretching ahead. I always dreamed of road trips as a child, imagining cruising the idiosyncrasies of the British Motorway System. I'm finally getting to do just that.

There are a few pictures from the trip here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.