I've always been a little nervous about guided walks. From the awkward, rather typically British issue of trying to identify your fellow walkers at the outset - ideally without actually asking anyone - to the tricky etiquette of dispersing at the walk's end, they're a minefield. I once thought I'd like to lead walks - the idea of ambling around places I love with a respectful and engaged bunch of people both asking questions and adding their knowledge was attractive, if unlikely. Of course the reality is often different: bored tourists "doing" the sights, loudmouthed know-alls trying to upstage the guide, people with no spatial awareness causing minor traffic incidents. Guiding walks wasn't for me. In my attempts I also realised a simple truth: firstly most people just aren't as interested in the minutiae as I am. I've often thought I was boring or lacked the capacity to engage people - but as I've grown older I realise I'm just engaged differently. I've learned to live with this, and find myself surrounded by people who are at best encouraging, but at the very least tolerant of this. So today I approached a group of unlikely looking people assembling near Tower Hill station with some trepidation. We were going on a walk together - which for someone who jealously guards his excursion time, was a remarkably intimate association with strangers.

Today's trip focused on locations from The Long Good Friday - the 1980 movie which launched Bob Hoskins on his path towards being the nation's 'loveable villain' figure in Harold Shand, and which almost didn't see the light of day due to the inclusion of the then horribly ever-present IRA as the bad guys. Or perhaps more accurately as the worst of the bad guys - there are no good guys in the film. In some ways, despite the brash edge-of-the-eighties optimism, the glamorous yachts and the presence of some weirdly prescient tropes which would haunt London for decades to come, the movie has no redemptive ending. My first viewing of the movie years back left a couple of impressions - that London was unrecognisable for the most part, and that it kickstarted a good number of British acting careers. John Mackenzie's clear vision that this should not be the London of red buses and black cabs had wrong-footed me. But as I've walked the hinterlands of the city over the years, I've come to recognise Harold Shand's London - sometimes it is buried, sometimes it lurks in the most unedifying areas, often it requires a mixture of research and imagination to conjure it from the anodyne glass and steel of the modern city. But it lurks not far from the surface, buried under the very Thatcherite dream which Hoskins invokes as his yacht passes under Tower Bridge at the beginning of the movie. The regeneration of the docks, the opportunities for investment, London positioned as a European capital - calling the shots, not taking the bullets. Those predictions which must have seemed so outlandish to anyone who knew the dereliction of the Isle of Dogs and Royal Docks in the 1970s, now elicit a gasp of recognition followed by an ironic guffaw: the European dream is close to being over, the '1988 Olympics' which Shand proposes happened - if a little later than scheduled.

Our guide was the placid, knowledgeable and powerfully-voiced Rob, who called the group to order and set out the plan. We'd walk for a couple of hours, visit a number of locations used in the film and chart the progress of Harold's dream towards the Docklands of today. He'd play us contextual clips of the movie on his iPad - so we could gauge just how much had changed and how much remained of Harold's manor. I surveyed my companions - there were of course stereotypes: the older guy who sticks to the guide like a minder and engages all of his time between stops in discussion, the gent with the expensive camera who wanders all over the place taking endless shots of everything but the subject at hand, the middle-class intellectual couple who roll their watery eyes at each other when the discussion has to be simplified or edited for the sake of time or sustaining group interest. We shuffled off, over the messy tangle of crossings outside the Tower of London, over the neck of Tower Bridge where Police were zooming to some sort of incident involving a group of yelling tourists, and towards the Thames near the huge concrete hotel. This was the first point at which imagination would be challenged: we were asked to picture warehouses - full of spice and indigo, a river teeming with ships waiting to unload. Some had waited weeks, some even longer. The Pool of London was jammed and dangerous - haunted by river pirates who took advantage of the vessels stuck here waiting to be unloaded - some in the most violent of ways. London needed new docks and new suburbs to support them - and so St. Katharine's Dock was constructed. By the time Harold Shand was mooring his luxury yacht here, the dock was deserted and in disrepair. Several of the large, impressive warehouses had already fallen to new development and only the Ivory House remained fully intact. Today the view was surprisingly similar if the skyline beyond the warehouses was discounted, along with the modern housing which had sprung into being on three sides of the basin. In the corner the Dickens Inn tumbled towards the docks, its provenance not entirely honest - being some form of reconstruction from recovered materials on a new site. The marina was busy with boats which would have rivalled Harold's for style and opulence. It was clear from the outset that this walk was going to deal in contrasts.

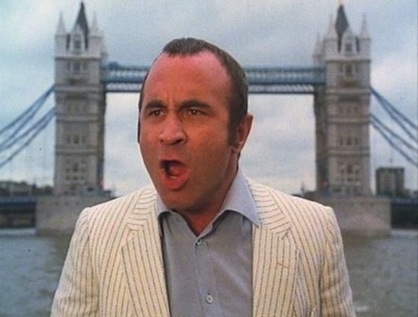

We progressed towards Wapping via the river front, recalling the shot where Hoskins was framed by Tower Bridge as he gave his rousing, patriotic call to 'the right people'. It quickly became apparent that this walk was unwinding two narratives - the fictional world in which the movie played out, and the uncannily similar events which followed just a few years later via the London Docklands Development Corporation. Shand's own 'corporation' fell prey to retaliatory attacks by the IRA and we saw the corner opposite Scandrett Street where, by virtue of a limited budget, a plywood East End boozer had been constructed to be blown up. We stood below, picturing the sight from the ground, where Shand's car had been seen arriving from the narrow street beside the then abandoned school buildings. Just a short walk around the corner we found the squat, yellow brick St. Patrick's Catholic Church. Apologetic and a little featureless outside, the interior was elegant and lofty, with brightly decorated iconography and dramatic columns climbing to a surprisingly lofty ceiling. Outside we strained to see St. George in the East over the rooftops, as the scene where Shand's mother narrowly escapes a car bomb was a composite with Hawksmoor's striking edifice playing the exterior while St. Patrick provides a fittingly non-Anglican interior. We didn't head for St. George this time - but I'd spent enough time stalking the environs to be able to picture the switch perfectly. Around the next corner we found Dundee Street, with warehouses now converted into flats and offices. Above the street, bridges crossed between windows completing the image of gentrified dockland living. It was here however that a young Gillian Taylforth played the young women who discovers a dying security guard nailed to the beams of the floor in a perverse play on the film's title. The religious imagery is deftly done - temptation, betrayal and sacrifice played out in the slightly distended timeline of a single day.

Approaching the Limehouse Link Tunnel, the story shifted from the plans which Harold Shand had for a new city, to the events which took place here in the 1970s - Michael Heseltine's helicopter flying low over the abandoned wasteland on a return from an abortive excursion to Maplin Sands. His development of the LDDC with the plan to free the area from the shackles of council inertia and the too-and-fro of the same old guard in Parliament. He gives them comprehensive planning powers and just enough money to buy land and sell it cheap. At the same time, London Transport scoff at serving the area with any sort of serious service, and instead the Docklands Light Railway springs up - a budget train-set to fit the low-rise developments which are springing up. Heseltine wants to see people living and working here again, but it's slow - painfully so - and far too glacial for Nicholas Ridley who follows him into the Environment brief. He has a new vision: leveraging private capital to spark life into the Isle of Dogs. The Canadians arrive but want the infrastructure before they commit. Soon the DLR is expanded, the Limehouse Link digging begins - possibly the most expensive road project ever in the UK at that point. Slowly the towers climb from the water. But - abruptly - the market crashes and everything stops. The abundance of empty office space across the major cities of the UK and Europe makes a folly out of One Canada Square, the tower which glowers over the island with a baleful pyramid and an ever present smear of smoke at its apex. It may as well have been burning money.

Then the IRA make their own leap from fiction to fact - this time in a genuine and devastating way. On 9th February 1996 the two-year long ceasefire ended with a huge explosion under the DLR on Marsh Wall. Two men, local newsagents, were killed in the blast which left a huge crater in the ground and destroyed one building, and damaged two others seriously. I remember a DLR trip through the area some weeks after the bombing - the shell of the Midland Bank building with its empty windows and flapping blinds standing eerily beside the track as we swerved and dodged around the tight curves between docks and offices. This and a range of other IRA actions in the City of London and Manchester achieved what no amount of government money had managed - it created a market for decent office space. The development of Docklands was perversely rejuvenated and soon Canary Wharf was at the very heart of the plan. Soaring from the mirror-like surface of the former docks, new office towers grew swiftly with the emblems of international banks blinking into life above them. As we arrived at Canary Wharf it was nearly impossible to imagine this was the site of Harold's betrayal in the movie. His blood-soaked stagger from the yacht with a Lear-like howl towards a focused, cool Helen Mirren took place at a point before any of this could be imagined. The deserted dockside with its rank of low sheds along their edge didn't promise this kind of future, and at this point in the movie with his betrayal complete his scheme to bring prosperity seems unlikely to succeed. Now, the impressive brick sheds are the only surviving reference point - housing the Museum of London in Docklands, they are busy with visitors. Across the dock, the glassy torpedo of the new Crossrail Place appears to be moored alongside the office towers, the uncommissioned platforms sitting far beneath the water. The walk ends here, the story complete and Harold Shand's dream delivered despite his almost certain fate at the hands of a young Pierce Brosnan. Using the movie as a lens through which to view the change wrought on this part of the Isle of Dogs was a surprisingly clever ruse, and I can't help but feel that our rather oddly matched group of walkers would never have been assembled for a straightforward 'Docklands history walk'. They might have sniggered and sighed at the names of Conservative politicians of the 90s, but in doing so they missed a point - the plan in its original form was to remake part of London very much in its own, older image. What happened here, what has grown as a strange, disembodied and distinctly transatlantic city beside the city, is as much the result of subsequent governments of both parties' losing grip on the financial sector.

Suddenly, I was alone in the midst of the new city. The group dispersed, even the guide's most ardent hangers on finally leaving him to head for the station. The small square, tucked in beside the replica of the West India Dock Gateway with its elaborate model ship, was windswept and empty. Construction on both sides of the square meant no-one much was heading this way. I tried to decide what to do for the best. The guided walk had taken a little longer than I expected and I'd not thought through my options for the afternoon. I decided to grab a bite to eat before trying to complete a stretch of walking I'd meant to cover for some time - the perimeter of the Isle of Dogs. First I had to negotiate the mall which sits under One Canada Square. I'd been here before, many years ago, and I knew there was a small supermarket near the DLR station. Getting there was a challenge - I'd never arrived at ground level before, and even the concept of 'ground' was less than fixed here. I found a lift and ascended from the sub-zero floors towards the surface, which was in fact the level of the bridge carrying people across to the soon-to-be Crossrail station, finally finding myself at the store near the DLR which was, today at least, closed for engineering works. Purchases made, I retraced my steps out into the broad square and perched beside a cool fountain to eat and plan a little. It didn't take long for a uniformed 'Canary Wharf Estates' employee to take an interest. After wandering around the general area for a little while he plucked up the courage to come nearer. "Going to be long?" he enquired? I took a silent slug of water and said "Not much longer, just having a breather before I walk a bit more". He looked like he wanted to ask more questions - but he was young, inexperienced and a little unsure. I suspect he'd have found it easier if I was a rolling drunk or an itinerant begger - someone he could legitimately move on using the powers he had on the private estate. Instead I was a reasonably polite, reasonably tidy chap who had happily answered his question. "Well, take care then - and no hanging about" he managed before he scuttled back towards the building. I dusted myself down a little, took some defiant shots of the building towering above me, and headed along the edge of Crossrail Place. At the end of the walkway where the building petered out and the dock resumed, things were a little ragged. There are still rough edges to the Canary Wharf estate, and if one walks to the perimeter they soon become apparent. Turning alongside Bellmouth Passage I climbed stairs and crossed a street near empty offices, finally escaping the estate via Trafalgar Way. The staffed sentry post was active, the private police force beckoning cars forward to have credentials checked while flagging buses into the site. I looked across the broad empty area surrounding Billingsgate Fish Market, and across to Balfron Tower and the towers of Stratford beyond. It was a surprisingly sunny afternoon, though you'd never know it inside the estate, where the buildings reflect only each other.

I found myself not far from an area I'd walked some while ago, near Poplar Dock Marina. Ahead was the route to Blackwall and Leamouth, but I turned south cutting through a carpark to regain the A1206 as it started a long curve around the island. It soon became apparent that trying to use the river path was going to be a fruitless and time-consuming endeavour. The path was frequently broken by developments, sending me scurrying back and forth to find a route south. Instead, once over the impressive Blue Bridge I stuck largely to the main roads, with a brief excursion into the Samuda Estate. This rather forlorn range of London County Council blocks from 1965 looked tired and careworn, and at their centre stood the stark and impressive Kelson House. This twenty-five storey tower, made up of neatly interlocking three-level maisonettes, was modelled on Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation, with access via a separate slender tower on its western side. It wasn't as graceful or bold as Goldfinger's similar efforts, and was altogether more workmanlike and British in appearance - a building which could grace any city centre perhaps? That it survives is testament to a tenacious island population who have, on the whole accepted incomers and immigrants rather like any dockside community. However, in the 1990s the area had a period of more chequered history, electing the first ever British National Party councillor in Derek Beackon. Beackon appeared to be as surprised as anyone to find himself on Tower Hamlets Council, and struggled to manage the complexity or scale of work expected of him. Perhaps not surprising as his prior role in the party had been as 'Chief Steward' - effectively the organiser of the team of Skinhead bodyguards who circled the leadership in public. Beackon's 'rights for whites' agenda was perhaps surprisingly aided by the local Liberal Democrats who published their own literature complaining that the predominantly Bangladeshi group rehoused from Limehouse when the Link Tunnel was built were given priority in 'luxury' accommodation. With Labour and the Lib Dems locked in an idealogical struggle during the 1993 election, Beackon crept in by a margin of only seven votes and immediately failed to comprehend what was possible at the local level. His colleague councillors walked out in protest at sharing the chamber with an immoderate and loud-mouthed fascist. When the seat was again contested in 1994, Beackon was ousted by a concerted campaign by Labour, and while the white working class roots of the island persist, there is at least a sense of a shared community in this oddly isolated zone again.

Pressed for time, I began to consider my options. The plan to circuit the island back to Limehouse was possible, but I found myself rushing ahead and not taking in my surroudings. A steady procession of buses beside me on Manchester Road had been reassuring at first - a potential quick way out if time got tight - but now they felt like a nagging pressure. At Island Gardens I decided to rethink my plan. With the DLR out of action the square outside the realigned route was busy with people teeming from the Rail Replacement Services. Beside the shiny, winged modern station the brick viaduct which had originally carried the rails here was still standing. I recalled previous visits, long before the railway burrowed under the river, bailing out here at the end of the line and regarding Greenwich across the river from a bench in the small park. Seized by a sudden desire to relive this experience, I headed into the gardens and found my way to the river wall. The Thames buzzed with life - river buses and motor launches scudding over the brown waters. The Greenwich foot tunnel's domed entrances flanked the park, emerging beside the impressive bulk of the Royal Naval College across the river. Beyond, green space stretched away up towards the observatory. I lingered for a moment, before heading back to complete my loop around the island by bus. There was unfinished business on the island - and much to be explored within the deep loop of river - but for now at least, it was time to head back to the mainland.

Newbury Park station had become something of an unsuspecting transport hub today - with services from Liverpool Street terminating short a surprising mass of passengers were being directed to this usually rather sleepy loop of the Central Line which swings east to the edge of Greater London. Getting out to Stratford had already been a slow and steady process, but now I found myself joining an unexpectedly busy Hainault-bound service for the final few miles to my destination. Plunging back into the earth after Leytonstone, we emerged at the tight curve where the Underground lines divide and ascend to assume the alignment of the former Great Eastern Railway line to Ilford. Almost everyone got off the train at Newbury Park to scramble for the buses departing from its curious modernist half-pipe shelter to destinations east, and suddenly we were rumbling along almost empty, high above scrubby grassland and distant lines of houses. Despite not being as far east or north as many of my walks in this quadrant, this zone had an unsettling sense of being at the very edge of things. East of the line, paddocks and yards gave way to rising ground and a promise of distant woodland. Meanwhile, west of the railway, the gothic upper section of Claybury Hospital's water tower glowered over a broad smudge of bare wintry treetops. Alone in my carriage I stood, crossing to look from each window in turn. The border between Redbridge and Essex ran a little north of here but I was unlikely to cross it on this walk. Instead I intended to head west and south, joining together some remaining fragments of the ancient Forest of Essex and crossing the route of other walks. While a let-up in the weather had been promised, the sky remained a featureless slab of purple-grey just now. Snow threatened on the sharp wintry air, and I wondered about the wisdom of attempting this in February, but these walks are precious escapes and I was determined to press ahead.

I decided to stick with the train to its final destination, descending from the island platform at Hainault to an inconspicuous exit onto a quiet suburban street. I set off into the chilly wind, noting virtually no sign of humanity aside from a local slopping along in low-slung jeans, hood up, screen glued to face. He zig-zagged from pavement to pavement, bored and purposelessly playing chicken with the infrequent traffic as the long road stretched west between ranks of fading but solid villas. As I approached the interestingly named Fencepiece Road I spotted the distant tower at Claybury hovering ominously above the treeline. New North Road soon deposited me onto this busy arterial, lined by needlessly numerous hair salons and a few other businesses which huddled alongside the huge Old Maypole pub - a mid-century behemoth of a hostelry which tried to pass as an overscale thatched cottage but was betrayed by the curiously modern square towers which punctuated its curved faced. I set off northwards, intending to navigate the streets of a housing estate to cross towards Claybury Park. I noted the subtle climb becoming a steeper gradient as I meandered around a set of streets named for monarchs both real and imagined. As I turned briefly south to find an alleyway I caught a glimpse of the flat plains of land fringing the Thames between the houses. The sudden, sublime view spurred me onwards - and trudging through yet more streets getting increasingly tenuous in their royal links, I found my way onto Tomswood Hill. From here the views were perhaps even more impressive, and I eagerly crossed into the rough grassland fringing Hospital Hill Wood. The tower had dipped behind the trees, but to the south I had a clear view of a broad sweep of estuary from the distant blur of the Dartford Crossing to the glinting towers on the Isle of Dogs and the cluster of familiar silhouette-towers in the City. Turning west again I edged around the woods. The paths between the trees seemed inconclusive and very muddy indeed, and I knew that they would all eventually lead to the security fences of Repton Park, the sanitised name for the exclusive developments which now clustered around the former Hospital tower. There was no public access here, no way in without business and certainly no welcome for a lone walker with no legitimate purpose. Instead I decided to walk the wooded fringe of the park - part of the vast grounds in which the Asylum had been built. Repton's design. The architect's name was an acceptable substitute when evading the site's true purpose for the Estate Agents literature, and building to his design was finally completed in 1893 after municipal delay and industrial action. It is of course always easy to dismiss the ring of County Asylums which surrounded London as places of horror and misery - but Claybury was built to surprisingly high standards, and hosted the first ever laboratory to investigate the pathology of mental illness and numerous groundbreaking rehabilitative projects. Aside from that, the hospital housed the typical mix of the seriously mental ill, the elderly, the poor and unlucky and those judged too morally compromised to retain their liberty - almost 4000 patients at the peak of its activity. Passing into the NHS in 1948, and enduring despite the Acts of Parliament in 1959 and 1983 which saw care shift from institutions towards the community, the hospital - slowly deteriorating in fabric - finally closed in 1997. Then began a long public enquiry into the planning of the residential development on the site, and how many of the original buildings would be retained in the privatised and enclosed scheme which now placed an obstacle across the ridge of land. That said, I recognised too that it's unlikely I'd be walking this impressive green swathe of parkland had the site not changed in purpose. The surprisingly large park swung around the south-western edges of the woods, with Claybury Hall - an impressive manor turned exclusive apartments following a stint as a Health Authority HQ - peeking above the trees a safe distance from the Hospital. As I reached the western edge of the park I met a steady stream of dog-walkers heading in from Woodford Bridge, a rather quiet island of habitation which seemed to be cut-off from its surroundings. Everyone said 'good morning' here. It felt odd to be among people after such a quiet start to the day.

I was heading downhill again - into the Roding Valley, and towards previous haunts. The weather had closed in, and the dark sky seemed to be pressing down on the valley floor. I had a few choices here - heading north or south on solid ground to cross the valley by road - or I could brave a footpath which appeared to skirt a playing field near Redbridge Lakes, a private fishing establishment. Naturally I chose the latter, and after an abortive attempt to use the boggy football pitch to make my crossing, I gave in and returned to the muddy trail beside the lakes. At the gates to the fishing club, I turned aside, following the trail into a tunnel of trees while my feet slurped through deep mud. I slithered my way along the path, noting a tiny, unnamed stream trickling in bedside me, and heading for the river. It was raining in earnest now, and I was thankful for my coat as I trudged onwards wondering about the wisdom of taking this route after all. Suddenly, the path opened onto a broad stony trail under the splayed flyovers of the incomplete M11 interchange. I'd been here before and I felt my spirits rise at the sight of the motorway, greeting it like an old friend. I sheltered under the southbound carriageway while I studied the map and planned the next leg of my walk. Realising it was going to be wet however I proceeded, I decided to press on under the motorway and over the swollen, fast-flowing Roding, emerging on Chigwell Road at a filling station I'd visited on a previous Roding Valley walk. I turned south here, crossing the street and heading into the Orchard Estate. This clump of sullen grey towers clustered with low-rise blocks, felt down-at-heel - the rain did them no favours at all, and nor did the barricaded front of the beleaguered general store and community centre. There were few people around, and certainly none who were heading along Broadmead Road where the street rose gently to pass over the Central Line a little south of Woodford Station. The road had the feel of an early twentieth-century arterial route: generous villas set back from the street, with a broad, straight carriageway heading over the bridge. This alignment of the road replaced the former route along the wonderfully named Snakes Lane which was now severed at Woodford Station, the level crossing incompatible with the frequent electric train service introduced in 1947. This has turned the urban centre of Woodford into something of a cul-de-sac, stunted and off the main route to anywhere in particular, but popular with the locals nonetheless. Perhaps that's why these edgeland hamlets have gained the favour of quiet-seeking city types? The new road curved gracefully between the lanes and crescents of pleasant suburban homes, before coming to rest on the High Road from Epping on the fringe of Woodford Green. Traffic churned the gullies of rainwater onto the pavement, but up ahead the sun was high and the tarmac glared brightly back at me. I walked south, looking for an opportunity to leave the road and enter the forest again. I was close to The Charter Road, where I'd turned aside from the forest trail on my River Ching perambulation, and I was eager to rejoin the path close to where I'd left it.

After a march along the road through the forest, passing numerous private schools and nurseries which seemed to be a key industry in Woodford, I found a chance to regain the forest trail at Oak Hill. The path divided two cul-de-sacs, immediately turning into a muddy gully surrounded by trees. I slopped along, wondering how wise this was but still eager to walk the forest rather than along the surprisingly busy A104. There was some semblance of a surface in places - yellow stones lurking a little under the surface which provided some stability - but mostly it was a thick carpet of decaying leaves and a slick of watery soil. I tried to hug the margins of the path as I'd learned on my previous walk, but in places this just wasn't possible and I was reduced to a ginger skitter across deep puddles. My trusty boots did me proud again, keeping my feet dry and generally sinking deep enough to ensure I retained a vertical position. The path broadened briefly into a meadow between the road and the forest and I had a final chance to escape onto solid ground - but no way was I going to compromise, not now I had a layer of red clay on my boots and trousers. I was determined to press on. Shortly after plunging back between the trees, and after one of the wettest and muddiest areas I'd crossed so far, the path solidified. Up ahead the railings of the bridge over the North CIrcular could be seen. I'd rather looked forward to this crossing - this symbolic boundary which I've crossed and re-crossed during so many of my walks. It didn't disappoint. The footbridge cut across a section of the road enclosed by the forest. Looking east, traffic slowed for the junction at Waterworks Corner - where I'd have emerged too if I'd taken the road instead of this path. But to the west the view was majestic - the dual carriageway lurched north between the trees, opening a view over the Lea Valley. I could see the distant towers of Edmonton Green, and a shimmering surface of reservoir on the horizon. I spent a while watching the road before moving on. The next patch of woodland looked fairly small on the map, skirting the vast covered reservoir to the east, and crossing another footbridge into a larger area of forest. It was a slog through some exceptionally muddy terrain though, and I wasn't sorry to reach the solid surface of the second footbridge. The road beneath was surprisingly quiet despite trailing in from Tottenham and Walthamstow. Beyond the bridge I found a broad grassy area with a well-worn track leading across it. A small family group of dog walkers sporting muddied wellington boots passed by. More confident on this terrain I struck out ahead through the tall grass, my boots getting cleaned by the deep foliage as I walked. My confidence was soon proven to be misplaced: the track reached the tree line and dipped down a steep slope to gain the forest floor below. The slope was a mudslide. A near vertical slither at the least muddy spot, and a treacherous slope of sloppy clay elsewhere. The family with the dog had looped back and passed me, and the sight of them toppling, sliding and slithering down the hill put me off any attempt. I had to get a train back home tonight and a generous coating of mud beyond that I'd collected already was unlikely to sit well with with the guard I suspected. Instead I edged around the plot of land seeking a different exit. A small field of allotments was below, and there was a potential access onto the entrance road serving them. However, looking at a disgruntled gardener wheel-spinning his aging Volvo to gain traction suggested this wasn't going to work either. I felt a little thrill of concern - a kind of range anxiety perhaps - which was mostly unfounded: I could retrace my steps over the footbridges and back to the road of course. But it would be a long detour and would take some time. I realised I'd not eaten and I was feeling the effects of the walk so far on my feet and my stomach. It was a dispiriting moment. I walked the edge of the road, trying several possible routes down the steep slope to no avail, until I came back to the footbridge. It seemed I was retracing my steps.

Crossing the footbridge, I noted some seemingly well trodden paths down the clumpy grass of the embankment on the northern side. On investigation it was a fairly straightforward scramble down a grassy bank, and I soon found myself directly below where I'd been moments before. I was relieved - I'd had to track back a short way, but at least hadn't needed to recross the North Circular. Instead I set off east, over the cattle grid to the junction with Woodford New Road. This long, straight and busy thoroughfare cuts directly south through the forest, and I was inevitably going to find my way back to it somewhere on this walk. Setting off I passed a couple planning a walk in the forest, who clearly had second thoughts on seeing my dishevelled and grimy appearance. The road was wearingly straight and busy, and the sun had made for a warmer walk than I'd expected after the wet, chilly morning. I soon passed the point I suspected I'd have emerged from the woodland if I'd been able to make the scramble: I was back on track. On the opposite side of the road there were further tempting paths leading into the trees but I couldn't chance another detour and stuck to the road, soon passing the entrance to Forest School where I'd walked once before with a former pupil. A route along Snaresbrook Road and through the scrubby forest edge suggested itself, but I continued to stick with the footpath I'd chosen, navigating the roundabout and heading east again onto Whipps Cross Road. This stretch of road along the edge of the Hollow Ponds and near the hospital was familiar from a disturbing and disorienting night-time bus journey from Bakers Arms a few years back. That bus journey was haunting and strangely mesmerising - the unfamiliar scenery and the stern Victorian architecture of the hospital looming out of the dark as I passed into unfamiliar suburbs had created a strange impression on my memory. It was made worse by facing a potentially difficult social negotiation at its end. Whipps Cross road in pleasant winter sunlight was wholly different. The ponds glinted, busy with wildfowl and well used by locals, while the towers of the hospital peeked benignly from behind their tree-curtain. I wondered if this would erase the odd phantasmagoria of the earlier trip? I trudged along, tired and hungry, my goal being to find food before deciding how to end this rather poorly planned excursion. I realised there was a more interesting route to be found on the forested side of the road, but I already knew I needed to revisit this area to reconnect it with Wanstead Flats, so staying dry and surefooted was no loss today. I slogged on, watching the traffic tearing by to reach the A12 as its controversial course weaved around the terraces of Leytonstone.

Relaxing in the lowering sunshine outside a ludicrously busy Tesco store, I ruminated on how strangely the walk had turned out. The dismay at needing to turn back, the slow hard slogging through mud, and the unsettling reconnection with an old memory had been challenging. But the last stretch leading to this spot had involved crossing a footbridge over the A12 in its concrete channel offering views south and west towards the city. The panorama had been striking, with the terraces of Leytonstone framing the distant towers and columns and setting them in a strange context. Things felt like they were swimming into focus. Nothing seemed far from anywhere else just here. I still had time and a little refreshed energy - so perhaps I could connect this walk to something after all? I recrossed the main road by way of the modern addendum to Grove Green Road which snakes across to reach the older victorian byway to Leyton. It was comforting to be making good progress on a quiet pavement, and the area was interesting - previously seen only from passing trains or cars, but surprisingly close to where I'd walked many times before. Passing under the low railway bridge with dire warnings to diverted buses, I emerged alongside the linear park which filled the tiny sliver of land between the road and the concrete gully containing its shudderingly busy modern counterpart. As it dawned on me where I was, I came upon Claremont Road. Or at least I came upon the stub-ended brick wall at the end of a tiny inlet where it had once been. There were no houses in the street, just about room to park an off-duty white van or two. Claremont Road had gone, torn apart by the deep cut of the A12 as it progressed northwards to join the M11. This was the site of the last stand - the occupation of this street by a group of protesters with considerable local support had delayed the road scheme. A tiny republic formed within the monarchy. A lawless but self-regulating community with a single purpose built watchtowers in the beleaguered street and strung nets between the homes to keep the bulldozers at bay. Meanwhile a single elderly resident made tea and gave advice to the young protesters. I imagined her navigating all of the strained emotions and romances that being caught up in that heady moment of resistance must have invoked in the young and idealistic minds. Calming, soothing and reassuring, she'd seen worse - a war, austerity, the rapidity of the modern world encroaching. Their petty dramas, even the bigger drama being played out via the siege at her doorstep must have seemed part of the flow of things. But now the street was gone, the A12 had prevailed and its traffic echoed by the end of what was left of Claremont Road. Progress had overtaken all of the events, large and small, and the towers and gates and allegiances had all been swept away. Coming upon the street by accident was a unexpected experience - when it crossed my mind this would be along my route I'd been convinced I'd missed it, or got entirely the wrong location - but here it was. The brick wall was a stark reminder of the fate that befell the residents of this quiet dead-end street which became a symbol of a wider environmental struggle in those fervent days.

I was beginning to slow down, my feet sore and sluggish after their trawl through the muddy forest. Grove Green Road stretched, straight and long, towards a crossroads where everything seemed to fall into place. If I continued ahead I'd end up reversing my recent walk around the Olympic Park, if I turned north I'd be heading for Bakers Arms and the site of a restless and strange night. Instead I turned south, crossing the bridge outside a busy Leyton station, people pouring from the entrance. I took the bus instead - making sense of this somewhat impromptu wander needed a slower pace of travel. My route cut across everything - from the valleys and ridges I normally use to guide me to my perceptions of some of the areas I'd covered. I'd demystified the horror of Whipps Cross and re-examined the view from the North Circular from a new vista. Sleepy, down-at-heel Hainault and the tower at Claybury seemed distant indeed - but the new links I'd forged brought them into my London mythology. The tongue of forest curling into the city needed further exploration for sure, but today this most ancient topography had given form to my wander. Thankfully, I slipped into the bus seat as we sped towards Stratford.

You can see a gallery of images from the walk here.

An empty stream, a great silence, an impenetrable forest...

Posted in London on Saturday 14th January 2017 at 11:01pm

Recommencing my explorations in a new year always feels uncertain and unplanned. Heading north to Scotland immediately after the festive season certainly helped me to relax a little, but after a week of catching-up with work and trying to recapture a sense of the normal following a long break, it felt exceptionally good to be putting boots on the ground once again. For a while, the weather had seemed likely to intervene so I hadn't made firm plans, content to watch the forecasts and warnings with a critical eye and with some undercover alternatives in mind. However, the snow shower that swept across the country had largely departed by yesterday and today had dawned dry and frosty. An eerie early mist drifted across Wiltshire as I sped eastwards into the promise of a glorious sunrise, and I finally dared to make some hasty plans for the day ahead. I was a little surprised at my own eagerness to get moving too - I found myself tumbling almost immediately onto a convenient Underground train and skipping my customary coffee at Liverpool Street in favour of finding refreshment along my route. So, much sooner than expected I found myself walking north along Chingford High Street towards a dark line on the northern horizon. While I tramped past the seemingly endless line of tanning salons and estate agents of Chingford I focused on the growing smudge of green in the distance. I was heading out of the city and into the forest...

The edge of Epping Forest was familiar from a previous walk last summer: I remembered how a sea of trees fronted by broad, open space broke against a resolute line of victorian villas, built for their views over this remarkable surviving swathe of ancient woodland - the people's forest as gifted by Queen Victoria. I turned east here, passing a mutton-dressed-as-lamb Tudorbethan hostelry which was in fact an over-gabled Brewer's Fayre and Premier Inn combination. This location on the edge of the forest, in what must have been an earlier twentieth century pub building, was fantastic. However its brassy, false provenance left the genuinely much older Queen Elizabeth's Hunting Lodge looking pale and ghostly beside it. The caricature of history was more photogenic and somehow more three dimensional than the real deal - this squat and haphazard limewashed block which had seen several hundred winters in this exposed spot before it's neighbour appeared and stole the limelight. The inevitable Interpretation Centre nearby was open, but the lodge was locked. A family shuffled out towards the venerable structure with a slightly disgruntled member of staff following to open up the building. They'd clearly hoped for a quiet January Saturday where the punters would be content with coddling themselves in the bar next door, leaving history for warmer opportunities. I crossed the street here to Warren Pond to assess the state of the footpaths through the southern reaches of the forest. A little ice topped the puddled ruts in the track and a remnant of snow lay on a pile of cut branches. I tested a boot on the surface and only slithered a little before the lugs of my soles chewed into a layer of sandy gravel. It felt viable - so my planned excursion could probably work as I'd hastily mapped it out. I turned east again and headed a little further along Ranger's Road. None of the passing vehicles obeyed the speed limit as they hurtled into Essex, a constant trail of taillights winking past me in the ominously dark skies which had settled on the rather bleak vista to the east, displacing the hope of winter sunshine. The road rose and turned a little to the north with the view opening out around me - a few feet ahead a tiny brick parapet was a tell-tale signifier of the presence of water - the inconspicuous River Ching. Beside it a battered and faded blue sign announced simply 'Essex'. I could start walking in earnest now...

The River Ching is a strangely unremarked watercourse which barely registers on the inventory of obscure London tributaries. It doesn't go anywhere of consequence, describes no occult arcs and bubbles fairly unimportantly through boroughs which don't regard it as a feature to be cherished or advertised. It rises to the north of the bridge on which I first caught sight of it, just beyond Connaught Water, and joins the Cuckoo Brook before passing below the bridge on which I stood and heading south into a wooded valley which skirts the high ground of Chingford. Here at Ranger's Road, the rather lively, narrow stream linked the great expanse of woodland to the north with the tail of the forest which still curls southwards and encroaches on the city. I crossed the street and passed a vehicle barrier before disappearing among the ancient trees of Essex. Initially there was a well made track with a screed of sand and stone underfoot, but as the path edged around the fence of a large property, the trail became a muddy bridleway. I passed a pair of horses being ridden back towards the road, their haughty riders not returning my acknowledgement, and then I was rather suddenly alone. The ground in the forest was thick with golden oak leaves, some slowly mulching into the sodden, black earth. This wasn't a result of the melting ice or a recent downpour - this woodland floor had absorbed the rainfall over long, wet centuries. It was probably never fully dry. The aroma of decaying wood surrounded me and twists of holly and ivy curled from around the bare trunks of the oaks. Slowly, as I pressed onwards, carefully keeping my feet out of the worst of the mud, the sounds of the suburbs receded completely. Rather suddenly I burst into a wide open space where the cloud cover had broken enough to let shafts of sunlight reach the frost, clearing it in broad patches. Whitehall Plain appeared to be a pleasantly grassy field, but on closer inspection was in fact a marshy trudge. The earth sucked at my boots as I tried to walk the edges of the path, using the deep tufts of grass for extra traction. It was hard to resist breaking the ice on the horseshoe prints, but I was already conscious that my boots and trousers had a thick covering of pale, Essex earth and couldn't risk an ankle-deep mud puddle. I made for the southwestern corner of the field, where a gap in the trees indicated the makeshift trail continuing south. The map was only partially useful here - this trail didn't officially exist, and I confess to some anxiety that I'd come a long way on fairly tricky terrain. Retracing my steps didn't feel like an edifying option at this point. At the corner of the field I was faced with a choice - and with a close encounter with The Ching which babbled invitingly close to the path. A small bridge crossed it here, but it was beyond a huge slimy pool of mud. I wasn't really sure that this was the correct way ahead - but the lure of the water was strong. I edged closer, finding the undisturbed ground at the river's edge more walkable. Suddenly, and rather surprisingly, I found my toes dipping into the watercourse. As the mud from my boots clouded the little stream and washed them clean, it occurred to me that this was the first time on my many riparian walks that I'd physically made contact with a river which I was walking. It was an odd experience, but satisfying too to see the patch of muddy water billowing away from me. My shoes didn't stay clean for long - after the bridge, the path disappeared into the undergrowth in a way which suggested it was far less substantial than the one I'd left before crossing the river. This couldn't be the best option - so I edged back over and through the tricky swamp to regain the path I'd left at Whitehall Plain. I was soon in a second wide field and making much better progress, occasionally the sun flickered through the trees and my footing felt steadier. A jogger appeared, huffing along the path towards me. I could feel civilisation returning.

My brush with the suburbs didn't last long - I crossed Whitehall Road close to the point where the Ching passed beneath a decorative but otherwise inconspicuous concrete parapet. At the other side of the street there were paths on both sides of the river - but the western path, running close to the back gardens of a crescent of houses, was just a little less muddy and overgrown in appearance. I was soon trudging along close to the meandering river once again as it ambled between the trees. It was cool and quiet beneath the canopy of branches, and now that I'd found my feet a little I felt able to wander confidently along the trail. Occasionally I'd dare to stray a little off the path to the bank of the river as it curled between the venerable trunks of the forest. The water was clear and free of litter here - and I found myself wondering how it would look further along it's route. As I shuffled through fallen leaves back towards the path I spotted a sleek, red fox standing watching me ahead. I slowed my pace and locked eyes with the remarkable animal, which didn't budge at all. It stood calmly regarding me with interest and perhaps some suspicion as I crunched along the stony track which had replaced the mud. Eventually, with only a few feet between us, the fox flattened itself to the ground and launched swiftly into the ferny undergrowth. I halted and stayed quiet in the hope of perhaps catching another glimpse - but all was silent. I checked my map - this track formed the access to a nearby house, and even had a name - Newgate Street. Suddenly, and unexpectedly, I found myself at a busy roundabout with the Ching passing underneath. A miserable drizzle was falling, and the cars were kicking up a dirty spray as they shuddered by. I spied a range of shops leading towards Chingford Hatch and headed that way to get a drink. As it happened, a small filling station with a general store was the nearest option and I slipped inside to avoid straying too far from my plan. As the door opened I was immediately hit by the acrid reek of over-cooking cheese - the powerful fumes from the Subway concession almost drove me out before I could grab a bottle of water, and certainly put paid to any hunger which might have been rising. As I tried to hold my breath through the achingly slow transaction, the sales assistant appeared utterly unconcerned by what I was now convinced was some sort of emergency in the back of the garage. I was glad to be back outdoors in the clear air of the cold, grey morning again.

To continue walking the Ching I had to leave it briefly, taking the southeastern fork of the roundabout and heading back into the forest. As I set off, I spotted the path I could have taken on the eastern bank of the river trailing in from Woodford Golf Club. The road began to climb a little, passing pleasant streets and delving back into a thick knot of trees. Soon I found the trail leading south, and after a brief slither down a bank between the trees in sight of a dog walker who politely pretended not to see my unsteady progress, I closed in on the river again, now running to the west at the foot of a steep bank. The path rose, leaving the river again and soon came up against the fence of Higham's Park. This particularly treacherous stretch of mud was hard going, and the temptation to flit into the more manicured environs of the park via one of the stiles which separated it from the forest was strong indeed. I persisted, and was soon rewarded with a wonderful view of a lake emerging from between the trees. The rain had stopped and the waters were still, broken only by the wakes of stately swans gliding across towards the furthest bank. I rested awhile, rather taken with the quiet spot nestled between the comparatively bustling suburbs of Woodford and Chingford Hatch. It was soon time to press on - and to leave the forest completely. At The Charter Road, near another neat concrete bridge, I left the river and plunged into a built-up avenue. At the end of the street, a footpath beside Highams Park School reunited me with the Ching in a scrubby triangle of waste ground where the various developments had left a void between their boundaries. A substantial part was given over to allotments, but this narrow and hemmed-in corner was useless and unloved. The river had changed - litter tangled around the railings, and the banks were strewn with discarded household items. It seemed barely possible that this was the same babbling stream which had first appeared in open country and which had accompanied me through the silence of Epping Forest. It was time to confront the urban face of the River Ching...

Many of the rivers I've walked disappear entirely at this point, submerged into culverts which sneak under the city, leaving me seeking telltale signs of their presence beneath. But the Ching remains almost entirely above ground, even when it cuts across the lower reaches of Chingford towards the Lea Valley. That's not to say the river is always accessible, and I realised that my route here was at best speculative. The Ching flows between the back gardens of long terraced avenues, and marks the boundaries of inaccessible school fields for much of this part of its course. But first I had to pass under the railway, with the river in a narrow channel beside me as I turned into the accurately named River Walk. The yellow brick viaduct arched over both the path and the Ching - but the Network Rail information panel identified the watercourse only as 'Stream'. At the end of River Walk, an end-of-terrace house was decorated with a mural depicting a white owl in flight, and urging me to respect nature. Here the river once again disappeared between streets of pleasant victorian terraced houses, and I had to detour around these to get to yet another school where a shared cycle and footpath joined the waterway again for a brief stretch. On the other side of my path tall blocks of modern homes were being built - the first of them already occupied, bored children staring down at the footpath - on the site of Walthamstow Stadium. The map showed the distinctive oval of the dog track preserved in the footprint of the new homes, it's iconic fascia memorialised to front the development. The white wall with its distinctive lettering looked like a bright and stark headstone against the grey glass behind it. It was the spectre of a place - a lost memory that meant little to the families which now lived behind it in Parade Gardens. The river disappeared briefly underground here to pass under Chingford Road - a busy tide of traffic prioritised over a few of us hapless pedestrians navigating a complex of crossings. When I finally arrived at the other side of the road, the river re-emerged, sluggish and clotted with junk, beside the access road to a vast Sainsbury's Superstore. The temple of retail was so huge that a Holiday Inn had been enveloped by its car park - or perhaps shoppers needed to break their visit and rest overnight after trudging the endless aisles? I braved the store, needing food and facilities. It felt a little odd to be surrounded by impatient, jostling humanity after my solitary forest walk.

Emerging from Sainsbury's refreshed, I noted that the early promise of sunshine was finally being delivered. The wet car park shone back at me, and I tried to appear as unassuming as possible as I slunk off to the edge of the site near the delivery bays where vast juggernauts of produce were disgorging into the store even now. On the map at least, a footpath appeared to edge around the site, shadowing the Ching as it wound around the regenerated footprint of the infamous Chingford Hall estate. I found the path, and followed it until it finally petered out at the edge of a further huge supermarket. While the bank of the river looked walkable for some distance ahead it was fenced off and marked as private land, with dire warnings for trespassers. I negotiated the edge of the supermarket car park and took a footpath leading into the quiet streets of the estate. Chingford Hall was one of the large-scale housing developments which promised so much in the 1960s, but became synonymous with urban decay and fear in later decades. Its towers were felled, one by one, and by the early part of the 21st century it had risen again in its new form - low-rise blocks in defensible cul-de-sacs, utility blocks with local shops and pubs, public space and playgrounds. But despite following the 'Secured by Design' playbook, Chingford Hall is still troubled by tensions between gangs, poverty and isolation. The local pub was derelict and open to the elements and the chip shop owner was nervously eyeing a gaggle of youngsters staging a half-hearted food-fight across a table. The quiet Saturday afternoon was palpably tense in a way I rarely sense in inner London nowadays. The roads mocked the river's hidden passage: Burnside Avenue, Ching Way. My escape from the estate was to be via more familiar territory - and since I'd left the supermarket I'd been able to detect the drone of the ubiquitous North Circular. At the end of Ching Way, a curved brick entrance opened onto the A406 near the point I'd crossed it months ago. On the estate-facing side of the wall an ancient VCR had been hurled at the ground, splaying it's archaic electronics across the path. I stepped over it and into the maelstrom of fumes and noise beyond. It was like stepping into a wholly different world. And perhaps this mad screed of traffic marking its border is why Chingford Hall feels so inescapable? The road marks a division between territories. Crossing the footbridge seems ill-advised, and the boundary must be defended. Despite standing above six lanes of pulsing hydrocarbon fumes, I felt able to breathe without the tight knot of tension which I'd experienced in the estate.

Descending from the footbridge, I felt oddly at ease. I was in familiar territory. The vast white slab of Costco rose above the trees, and signs at the litter strewn junction of Folly Lane and Harbet Road promised more industrial estates nearby. The land here is flat and open - part of the wide plain at the bottom of the Lea Valley which is filled with a tangle of watercourses and crossed by only infrequent arterial routes. As the North Circular bucked and swerved north towards Edmonton and my recent encounters with other tributaries, I turned west. The Ching was canalised here, running in a deep concrete channel with powerlines strung overhead. The lowering sun glinted from the water, and the clouds rolled dramatically over the valley. The conditions were perfect for this liminal zone, and I found a new eagerness to walk. There was only a little more of the tiny but persistent river left as it delved, arrow-straight towards the Lea. The road weaved around a pumping station complete with attractive workers' cottages, before crossing an aqueduct carrying a man-made drainage channel parallel with the Lea. Then suddenly, I found myself above the Lea, looking at the opening of the Ching's culvert. After passing under the aqueduct the river ended inauspiciously, joining the Lea as it curled around the banks of Banbury Reservoir. The sun was low over the water, and the march of pylons was a line of brooding shadow-walkers. I paused and tried to connect the tiny brook in the forest with this green, oily ending. It had been a brief journey in terms of distance - but it occurred to me I'd probably been able to stay closer to the route of the little River Ching than I had when walking other streams. I navigated the tongue of land which housed a rapidly disappearing industrial estate. I'd walked here only a few months ago and all had seemed intact, but now buildings were hollow shells with last year's calendars flapping on their exposed interior walls. I learned later that this woudl be part of Meridian Water - a new suburb rising from the dust of Edmonton, mercifully upwind of the Waste Incinerator - at least most of the time. This eastern part of the site will be reserved for employment, and linked to new housing by means of The Causeway - presumably an upgrade of the deeply pedestrian-unfriendly bridge carrying the A406 towards Angel Road station and the west. Looking back, I didn't consider these vistas threatened or this land desirable - but now the bright frontage of the tiny, closed greasy spoon caff on Towpath Road seemed oddly poignant. As I walked south the wind carried the weird, disembodied cheers and songs from White Hart Lane over the valley, away from the bright halogen of the floodlights.

At Stonebridge Lock I rested outside the fine little café which seemed a world away from it's near neighbour just along the river. While the informal and friendly owners shambled around preparing drinks and snacks for the surprisingly steady flow of visitors, cyclists relaxed in the sun and thirsty dogs ambled around their owner's feet. I bought a coffee and sat outside, resting my legs and contemplating pushing on further than Tottenham. I felt better than I had for a long while, and I thought I could manage it. But I also wanted to rest and mull over the strange contrasts I'd experienced today. The bright winter light was lowering to the south west, and the Lea Navigation was a reflective river of black water. The edges of London are constantly torn and remade but somehow its waterways persist - in the margins of developments, delineating parcels of land, and rising in protest at being curtailed or culverted. Choosing to walk these ancient routes has linked the disjointed fringes of the city in a way I'd never have expected. I sipped my coffee and contemplated my next move.

You can see a gallery of images from the walk here.

I'd worried all week about whether my new winter coat would arrive in time for this walk. Commuting to work in sub-zero temperatures during the past week had alerted me to the simple fact that I was ill-equipped for a December jaunt, reminding me of the cruel winds which whipped around me as I strode out into Essex at the end of last year. I'd half-heartedly planned several potential walks - and I was prepared to change my plans and have a day of train-related travels if the weather turned ugly. However, the coat arrived and as I rather snugly skittered out of Liverpool Street on a local train, I realised that a decent pair of sunglasses might have been a more pressing purchase for today. As we snaked across onto the fast lines and sped out towards the east, the low winter sun glared into the windows, glinting from the cranes which surrounded the edges of the Olympic Park at Stratford and throwing long shadows from the half-built towers of East Village. It was a relief to be moving - the last few weeks had been challenging and felt like a hard slog at work for both of us, and the chance to get pavement under my boots again was welcome. The half-formed plan which I'd settled on was to return to a place I'd formed a perhaps unfairly poor impression of to start my walk: Chadwell Heath. I was on the trail of the Mayes Brook: a tiny waterway which rose hereabouts and meandered south and west towards the River Roding at Barking, forming along its course the perimeter of one of the most significant public housing schemes ever built and providing a boundary between boroughs for a good deal of its length. I'd crossed the tiny but significant brook on my A13 walks, found it interesting and wanted to explore further. That walk though had a clear purpose, so I had to content myself with laying down a marker for future travels. It was curious how these furthest eastern expanses of London, which had seemed both a formless suburban sprawl and an almost troublingly dark place at first, were now filled with these streams and byways which I felt an urge to understand. I felt like I was slowly coming to know the territory, pieces slipping into place as streets were crossed and re-crossed, the edge of my ever present range anxiety slowly pushed back towards the coast of Essex.

My return to Chadwell Heath did a little to soften my previous opinion. On a bright winter morning, the walk down from the station to the long straight High Road to Ilford was pleasant, and while the street was still a collection of enterprises barely hanging on in their crumbling mid-century parades, it was a least a little more cheery. On the corner where I joined the main road, the imposing 1934-built Embassy Cinema building had become the unspecific 'Mayfair Venue' - apparently a banqueting suite in a somewhat unlikely spot. Across the street, the urban centre petered out into a long run of domestic appliance repair centres, used car lots and the apparently ill-starred 'Tranquility Centre' - formerly a tropical fish emporium. My target was an unpromising alley beside a petrol station which led to a bridge over the rails I'd just travelled. As I reached the top of the bridge the sun crested the low roofline of the houses and the scene was surprisingly illuminated from the south. Shielding my eyes I picked my way along the path leading to Green Lane and the entrance to Goodmayes Park. The park opened out into a broad sweep of green with a glassy black lake stretching along its eastern side. Through a broad refuse trap, and behind a boom restricting pollution from entering the carefully cleaned up lakes, the Mayes Brook trickled in from its source. The park was quiet, with a few distant joggers and dog walkers crossing the bridge which separated the upper and lower parts of the long lake. Straying from the path I took the well-worn gravel track which edged along the water, and from the southern tip of the lake I looked back at where the brook entered the lake. So little of the short waterway is above ground, making these occasional glimpses precious. Turning south again I headed out of the park by crossing Mayesbrook Road - one of the few nods to the presence of the stream here. Looking east, the uniform houses marching into the distance marked the western edge of Becontree - when completed in 1935 the biggest municipal housing development in the world. Straddling the Boroughs of Ilford, Barking and then remarkably rural Dagenham, the estate was extended twice before finally being fully absorbed into the new borough of Barking and Dagenham. From the air, the streets fall into regular patterns of straight crosses and fans of stacked crescents. The rails that once ran along Vallance Avenue to carry building supplies the estate are long gone, and the vast estate now relies on the spreading arms of the Great Eastern Railway and the District Line which it sits squarely between. Crossing another street I enter the unimaginiatively named Goodmayes Park Extension - a broad sweep of close-cropped grass divided into football pitches, with an allotment on the western flank. The path edges around the pitches, skirting around a range of pavillions and changing rooms painted a drab municipal green with windows fully boarded up. Somewhere under here, the brook runs south and west, towards Goodmayes Lane. Above the tree line a formal facade and clocktower indicate the site of South East Essex Technical College - latterly the University of East London. Built to provide education for the new population of Becontree who were inconveniently split across three Local Education Authorities, the campus survived until 2006 when UEL rationalised its estates and these imposing buildings were redeveloped as housing. The main block is named Mayesbrook Manor - the water, it seems, is never very far from the surface.

It's only a brief escape from parkland - long enough to navigate the junction of the busy and broad A124. I find a small corner store here and buy water. In my urge to get moving today I've neglected the usual preparations, and the walk so far has been surprisingly warm. Across the street I see a tell-tale patch of reeds behind green railings. Looking down from the street Mayes Brook trickles slowly between carefully reinstated habitat, a wild thatch of grasses beside it waving in the breeze. Beside the nature reserve a grand gateway opens onto a broad pavement leading into Mayesbrook Park. The line of green space which runs along the course of the brook - whether present above ground or not - is almost unbroken, and I'm soon walking a broad grassy trail close beside the stream which flanks Barking Football Club's home ground. A vast modern sports facility fills almost the entire width of the northern part of the park and through the trees and fences I spy a lurid purple splash with a familiar angular font - this is another London 2012 legacy artefact. That said, the sports centre appears well-used this morning, and the ranks of football pitches which spread south into the park are equally busy with games formal and otherwise. I stick to the western fringe of the park where the brook curves through new drainage swales and wetlands, created to cope with the ever-troublesome waters of the brook in flood, an event anticipated to be more frequent and dramatic as the earth warms. An arm of the brook passes under a squat bridge with a low brick parapet, draining into the broad lake which fills a former gravel pit. These pits were originally separated by a long narrow causeway leading to a broad circle for turning the plant which dug and carried gravel - this is reputed to have given the park its local name: Matchstick Island. The park was planned on a grand scale - its sporting facilities matched by sunken lotus gardens and stepped verandas. The newly transplanted inhabitants of the Becontree and Leftley Estates would enjoy the fruits of inter-war municipalism until the 1980s when a lack of repair and vandalism led the Borough to remove the sunken gardens. The lakes remain, with the carefully planned wetland course of the brook curving around them to exit the park under the District Line. I lingered in the park for a while watching Canada Geese massing on the wide concrete slipway into the lake. I could have hung around longer too - It was a perfect morning to be out here, and there was an uncertain distance to go - so reluctantly I pressed on out of the park into a place which doesn't exist...

Railway station names are not nearly as fixed and unchanging as they might sometimes seem. In London most especially, the plethora of competing companies operating independent lines prior to nationalisation made for a confusion of names - often similar though relatively distant - in order to attract the lucrative commuters who sought a haven away from the city. Sometimes multiple stations co-existed confusingly with the same moniker - the multiple West Hampsteads which straddle the road north from Kilburn even today for example. As the fortunes of suburbs fall and rise and fall again, their stations names are extended or curtailed according to popularity and reputation. Equally, as the railways struck out into undeveloped territory during the Victorian and Edwardian building booms, the stations took on the names of wayside inns, manor houses and hamlets which have long since been swallowed by the ever-encroaching edges of the city. In this way there are many suburbs and districts of London which have grown around and subsequently adopted the name of their nearest railway station. But I realised as I stood outside Upney Station that there really isn't an Upney at all. The station is an unremarkble low-rise brick building straddling a road bridge in the style of many at this end of the District Line. Atop the building a spike pierces a large Underground roundel, the bridge extending beyond the building to cross the mainlines to Southend. I was now walking along Upney Lane - in traditional British nomenclature the road to Upney - and on the tiny parade of shops at the edge of the estate was an Upney Fish Bar - but that was the only hint of the name on the ground. On my OS map, and even on Google's map which is often tainted with unofficial user contributions, the area had no specific identity. It was a hinterland of Barking - or perhaps a premonition of Dagenham depending on your viewpoint. But it wasn't Upney anywhere. My stay in this ghost suburb was brief - but for good reason. Across the bridge, and just a few steps to the west was Eastbury Manor House. The house can't easily be seen from the north or east due to a rise in the land - and it seemed unlikely that I was approaching a survivor of Elizabeth I's reign as I tramped around the carefully laid out quadrant of an inter-war housing estate. The quiet streets were full of the smells of lunchtime cooking and still-ticking off-duty cabs. But suddenly the square opened out and beyond the wintery frame of empty branches, a tall brick manor house stood in contrast to the municipal housing around it. Now managed by the National Trust, Eastbury was built on high land which provided fine views across open country to London and the Thames by Clement Sysely probably around 1570. Its situation now is changed - but the sense of being at a high point remained as I walked the boundaries of the square of land in which the house sits. The tall ranks of chimneys and the surviving octagonal turret towered over the pleasant little council houses ranged around it - and it seemed an unlikely survivor. When housing was scarce and the modernising spirit strong, so many places of interest were bulldozed in the name of progress. But somehow, at Eastbury, the wonderful hall has survived as a museum and venue, open to the public at times. The name survives too in the Council Ward of Eastbury - and perhaps in truth that's why Upney never caught hold here? The ancient manor has prevailed in more ways than one.

I emerged from the deleted suburb of Upney at Ripple Road, where the old course of the A13 turns south east to head for Dagenham. The Mayes Brook surfaces again from beneath the gloomy slab block of Sebastian Court, passing under the road and emerging beside a wide strip of well-walked grass. An Environment Agency gate prevents vehicle access, but appears to allow pedestrians to walk alongside the brook here. The sun was bright and low now, and it was difficult to see far ahead - and near impossible to take photographs. I spied someone standing near a bush up ahead and trod carefully - the edges of the grassy path were strewn with the usual edgeland litter - the ubiquitous Polish lager cans, blue convenience store carrier bags, blackened fire-circles. As it turned out, two dog walkers were conversing on opposite sides of a mound of brambles. One of them moved on passing me by, while the other, a while haired older man with a muscular and enthusiastic Staffordshire Bull Terrier, hailed me: "I'm letting him off the lead. OK?". I replied that I wasn't with a dog, but I suspect my unease was still evident from my voice. He told me not to worry - he was a good lad, and just happy to get a run. There weren't many places in easy range for a good run, not which an 82 year old could get to anyway. I strolled along the edge of the brook chatting with this unlikely companion, the water trickling quietly beside us and almost eclipsed by the growing screech of the unseen but nearby A13. He had lived here on Ripple Road for over 40 years, and in Barking for almost his whole life. He'd leave if he could - but he felt he was too old for the stress of upheaval. Certainly, he envied me living in Somerset: "By the sea, eh? Lovely". Much had changed here, he thought - but lots stayed the same. It had always been tough - always a challenge to get on. The Asians earned his grudging respect - buying their properties and extending them, letting out rooms, moving out into Essex on the back of their investments. He didn't dislike them but he didn't trust them or the changes their now overlarge houses made to the area. The new wave of immigration from Eastern Europe troubled him more - the litter, the ruined green spaces, the lack of any sense of integration all worried him. He'd clashed with the young men throwing needles and leaving torn cans in the grass and they'd been rude and abusive - he thought the muscular, moderately wild-eyed but basically docile creature he led along the brook had saved him from trouble more than once. His quiet intolerance was fiercely practical - not motivated by politics at all. While it felt odd and discordant to be speaking in these terms so alien to my own view, he was clear that no political party had it right. The working class parties couldn't talk immigration without tangling themselves in guilt, and UKIP felt like Mosley's bully boys who were still an East End folk memory for his generation. We found ourselves at a steel palisade fence which fully blocked access into a broad green field bordered by the brook, the railway and the concrete viaduct carrying the A13 above them both. I didn't expect to get beyond the railway - but I'd hoped to get closer to the bridge. My companion told me that this had been installed after a group of travellers had parked on the field. The Environment Agency had sequestered the land after an expensive clean up, and dug a deep depression into the field to act as additional drainage when the Mayes Brook flooded. We turned and walked back - another access, through the rear of some former garages was also gated, the structure of the missing buildings clear in the concrete divisions on the wall. He told me the local residents had taken action, clearing the wreckage of the old garages and painting out graffiti. He felt that the locals did care about their area, but they were fighting a losing battle. We parted at Ripple Road - he headed homeward to watch an afternoon of snooker, and I turned east to get to the A13. I wondered about this man and his experience of change - a force which he couldn't control and had to simply accept - and marvelled at his oddly serene attitude to being overwhelmed. He was clear - the market hadn't failed him, it had simply not touched him or his fellow residents here. It's easy to condemn this generation with their almost casually inherent bigotry and their foolhardy referendum votes, but perhaps sometimes it's prudent to engage - to see this strange and complicated landscape through eyes which have seen its rise, fall and abandonment. I felt privileged to have walked a little of the brook with someone who'd known its journey.