It was a much-needed break. The last week had, for both of us, been fraught with difficult moments at work and a complication of evening events - some of which we'd certainly not signed up for. This hastily planned week off felt well-earned and long awaited - and followed a well-tested template: we'd head off east, spend a night near Epping Forest and a favourite restaurant, then cross the river and head for Kent. Our target this time was Margate - somewhere which, since my last visit in 2011 had seen enviable regeneration. There was a sense of optimism in recent writing about the place, and no doubt the opening of the Turner Contemporary Gallery had helped. Tracey Emin, former enfant terrible of the British art world turned maker of intricate and wonderful things, had not so much confessed to her upbringing here as reconnected with it. She was championing the place, much like Turner himself had centuries before. Margate was back on the map. However, I sensed I had some persuading to do of its merits. The last week had seen me getting out and about to a range of events which I'm sure were way more interesting to me than my wonderful and tolerant wife - and I was equally aware that a night on the edge of Essex was more self-indulgence in some senses. So Margate had to deliver for both of us. No small feat for a once-proud resort trying hard to rise up from the gloom of the late 20th century.

We arrived at the crazy, mock-tudor Premier Inn early in the afternoon after a trouble free drive. Once checked in and settled, I laced up my walking boots and headed out into the blazing sunshine. My target was to make a circuit around to Pole Hill and be back in time to prepare for our dinner reservation. I strode out onto Chingford Plain, all swishing grasses and insects, and headed for The Hawk Wood. I was soon beneath the trees, a cool but still humid breeze gently moving through them. Everyone I passed greeted me, from sweaty joggers to ultra-cool lycra wearing bikers who let me pass before swooping down into a bowl in the forest floor to gain momentum for their climb. I trudged on, hot but happy. The path turned east and south, starting to climb. I was tempted to head for other nearby new targets - but Pole Hill called. I climbed steadily, beginning to see paths I remembered from the spring, before finally bursting into the sunshine at the summit near the obelisk marking the Meridian Line. I rested awhile before heading down beside the golf club to enjoy another wonderful dinner at one of our favourite restaurants.

Overnight, something strange happened at the Premier Inn which left the entire building without water except for the restaurant. We'd realised during the early hours, but it wasn't fixed when I headed out early for a wander. I managed to have a disagreement with the staff too, who didn't think they could do anything but offered me a complaint card instead. I called customer services the moment they opened and had things resolved within minutes. Things don't often go wrong with my stays at these hotels, but when they do they've always been fixed on the spot, meaning that the attitude of the staff today was really something unusual. Undeterred we set off early for a gentle walk in the forest, starting out via the path I'd used last winter to find the River Ching. We ghosted the water, rarely out of earshot of it's trickling as we headed for Whitehall Plain, crossing the bridge and returning north via the still waters of Warren Pond. It was a warm but breezy morning, and this was the perfect way to shake of a slightly frustrating start to the day before our drive into Kent. We took the tried and tested route - onto the A406 spotting footpaths I'd walked just days before, then via the A13 over the marshes to the Dartford Crossing. The last few miles of the trip had the anticipatory sense of the seaside about them: big open skies and flat sandy land beside the road. I recovered memories of arriving at holidays as a child, and wished my father could experience this trip. I'm sure he'd say there were too many Londoners about, of course!

Our home for the next two days was the Sands Hotel. This rather grand seafront building is as much part of the story of the regeneration of Margate as the Turner. Purchased by an entrepreneur who thought he'd surf the wave of property prices as Margate resurfaced, he decided on a different plan. The two adjacent properties were knocked into a single, large building over five floors creating twenty rooms furnished and designed to a high specification. The rooms were stylish and beautiful, and incredibly comfortable. Breakfast and dinner was served in the impressive Bay Restaurant with a broad sweeping view of the skies and seas which had inspired JMW Turner. It was impossible not to love this place - and there's no doubt it did Margate's cause some good too. As of course did our first excursion into the Old Town with its maze of well-curated craft and vintage stores, and our visit to the Turner Contemporary - a remarkable space with an ever-changing roster of exhibitions and areas dedicated to using the arts to link young people to place. It was always going to be a winner for me. We met some fascinating people too - including the owner of a store who was branching out into manufacturing limited runs of clothing in vintage fabrics. Everyone was keen to talk about Margate, how it was changing, but how it was still offering a family holiday experience alongside it's changing identity. Not for the first time, I wished our local politicians could come and spend a few days here, just to get a sense of what was possible when a resort irons out the issue of what it's trying to be.

We realised somewhere on our first full day here that we'd like to stay away for an extra night - and a little research turned up the Abbey Hotel in Battle, East Sussex. Since my holiday had begun with a viewing of Edith Walks, the idea of heading for the south coast appealed and we made our booking. Saying goodbye to Dreamland, to the T.S.Eliot bandstand and the broad sweep of golden sands at Margate wasn't easy - but the journey through Kent and Sussex made up for it a little. The Abbey Hotel was well-named, as our room framed the perfect view of Battle Abbey across the street. We spent another evening in comfortable surroundings with some excellent food at The Chequers too, where we heard the rumour that our hotel had recently been filmed for a future episode of Channel 4's accommodation-based game show/bitch fest Four In A Bed, which was one of our guilty pleasure TV highlights. In the morning, over breakfast we tentatively broached this with the friendly manager. His observations on the show, the process and the kind of people who got involved were fascinating - and not far off our own!

I'd made a special request for our trip home which took us a little out of our way, but would bookend the journey perfectly: that we headed for St. Leonards on Sea to find the statue of King Harold and Edith Swan-Neck. A short drive through the countryside and the hinterland of Hastings later, we swung onto the pretty, well-kept seafront at St. Leonards. The blue water of the English Channel lapped on the beach, and the distant view of high white cliffs and broad sands was rather special. My only visits here had been to pass through the curiously named 'Warrior Square' station by rail, so I was pleasantly surprised by the town. We stepped from the car across to the green and there, unremarked and surrounded by a freshly-trimmed lawn were Harold and Edith. As we looked on, an old chap wandered over and pointed with his stick: "So who is it then?". We told him the story of Harold and Edith's journey to find him on the battlefield. He was amazed and delighted - and wanted us to wait to tell his wife too. They'd been coming to St. Leonards for fifty years from their home on Shooters Hill in Greenwich and had always wondered. They'd come to rather love the statue and made it part of their morning walk - and now, after all these years they'd chanced upon us taking pictures at just the right moment to have their mystery solved.

I took one more picture, capturing Edith's face as she gazed at the fallen King, before we headed back to the car for our long trip home. I've never been a proponent of the summer holiday - competing with the hordes for road-space, train seats or overpriced hotels - but our carefully-timed excursions have, in recent years converted me somewhat. This circle of Southern England had felt like a real break - a real chance to escape from things.

A gallery of images from our trip is here.

London's Other Orbitals: The North Circular - Part 2

Posted in London on Saturday 15th July 2017 at 11:07pm

The next bus stop is closed...

I just made it out of the rear doors of the bus, which had patiently sat on the roadside near the Big Yellow Storage building for whole minutes before it decided to make the automatic announcement. Through a surprisingly less convoluted route than I'd expected, I found myself just feet from the bridge carrying East Finchley's High Road over the A406. In fact, I was just several more feet from where I'd exhaustedly plopped into the seat of a southbound bus a few short weeks ago, a sweaty and dirty character - the cause of much suspicion among my fellow travellers. Getting off a stop early allowed me to regard the North Circular from above as I crossed the street and headed for the footpath down to the road. It was a strangely gloomy and ominous morning, with unexpected clouds tumbling overhead as I gazed east along the road. I realised that I'd talked a lot about the wisdom or folly of undertaking this journey when I wrote my account of the last walk, and that in the process I'd clearly managed to convince myself that this was an enterprise worth completing. It wasn't without some trepidation that I followed the curve of the slip-road down towards the woodland fringing the carriageway, noticing a hi-vis wearing photographer trying to get a really good shot of a bowl of foraged blackberries he'd balanced on a fallen limb. When I'd surfaced from the road last time, I'd felt the effects for several days afterwards - a heaviness of limb and a dry throat - which made me wonder if these really were safe for eating. He didn't seem to mind, pluckily popping in a berry as he posed the bowl for best effect, wincing at the tartness of the fruit. Rejoining the road at Glebelands Wood wasn't a bad thing - it made for a relatively pleasant initial stretch of walking, despite being close to the traffic. A fragment of the ancient Finchley Common, the narrow band of woodland bordered by the North Circular and bookended by a large Tesco Extra is one of the few surviving areas of ancient woodland in Barnet. At the eastern end, a narrow tract of green space running along the Bounds Green Brook joins it to Coppett's Wood, another area worthy of an exploration at some point. Today though, the woodland kept me cool while a tall fence separated me from the brook, at least as far as the superstore. I popped inside to grab provisions for the walk ahead - while I'd never be far from civilisation, the road was sometimes a difficult place to find sustenance it seemed.

On leaving the store, it was raining - just a little, barely enough to bother the shoppers piloting their trolleys towards the doors in fact, but nonetheless I'd believed the forecast and didn't have a coat. Leaving the retail park by a pedestrian entrance I found the Bounds Green Brook just across busy Colney Hatch Lane. The name reminded me of another of the great ring of asylums which circled London - this one the scene of a terrible fire in 1903 which altered to an extent the public perception of these hitherto mysterious hospitals. The asylum - later Friern Hospital - lay a little to the north, and when opened in 1851 formed the second Middlesex County Asylum. The elaborate buildings struggled on as a hospital until 1993 when the final patients were relocated in the community. During its surprisingly long tenure in similar use, Colney Hatch became notorious - for its sometimes harsh conditions, and as a receptacle for some of the most infamous criminals deemed insane - once housing Aaron Kosminski, credibly suspected of involvement in the Whitechapel Murders. The buildings are now, predictably in luxury residential use as the suitably anonymous Princess Park Manor. Ironically the grand gateway which stood open while the hospital was in use, is now very securely closed. To keep people in or out is perhaps an interesting question?

When day dawned, while some of the firemen pumping water from the brook below continued to play on the red hot débris, others began the terrible task of searching the ruins. Then it was discovered that the fire had claimed many victims...The Times, 28th January 1903

The brook was sluggish and algae-filled - and it reeked. A slow-running stream in the summer is going to become a little ripe, but this was the stench of sewage. Another watercourse which appears to be plagued by misconnected domestic outlets. The brook soon disappeared behind the fence once again, and after a few moments of walking along the road, I realised I was climbing along a slip-road towards yet another retail park. This one presented a bit of a barrier, but a path offering a way back down to the North Circular appeared and I was soon passing underneath the tall totems advertising carpets, pets and fast food. The road was running as slowly as the brook - with traffic merging into the centre lane to avoid some obstruction up ahead. As I trudged a dusty section beside car dealerships and vacant lots which supported a burgeoning blackberry crop, I spotted the embankment of the railway to Kings Cross up ahead. I'd rather dreaded this bit in fact. Here, the A406 passes under a long, low bridge. So long in fact, that it almost forms a tunnel under the swathe of lines and the site of former sidings. Beyond the tunnel, a large gasholder loomed - reminding me that safety wasn't far ahead. Nonetheless, I had to endure a few minutes of being hemmed up against the sweating, Victorian brick arch while six lanes of traffic howled and shuddered feet away from me. As it happened, the broken down car which had been causing issues a few yards back helped me out here - having finally sputtered to a halt just shy of the tunnel mouth. Thus I had a good, wide lane entirely free of traffic separating me from the main flow of vehicles regaining speed after slowing to negotiate the broken down car. The occupants of the stricken car looked strangely unconcerned, poking at their 'phone screens while they awaited rescue. I picked up the pace, my steps echoing reassuringly into the distance. The light at the end of the tunnel seemed brighter, and free of the rain which had threatened its presence in the form of a unconvincing drizzle so far. Once inside, the noise was remarkable - a constant swish of air preceding passing vehicles peppered by occasional horns and the thrum of motorcycles. I wondered if I should even be down here - but there was after all a footpath. I wasn't sorry to escape, bursting into the comparatively fresh air of Bounds Green. The brook ran in the open again beside me, and while it was still a little noisome, it was bearable to stray towards it where the undergrowth allowed for pictures. The road had collapsed into a single, broad carriageway with only a set of advisory markings dividing the east- and westbound carriageways, while the Piccadilly Line surfaced to pass above just a little way ahead. This area was once notorious for planning blight - the various proposals for improving the road almost all insisting on the demolition of houses on the southern side of the road. Now though, the attractive run of mid-century semi-detached homes seem to be tidy and all in use. But life here must be strange - the North Circular outside their front doors, and heading for a notorious pinch-point on its semi-circuit.

To someone who isn't as enthusiastic about road junctions as I - which is probably most people - the meeting of Telford Road and Bowes Road at a crossroads in suburban Arnos Grove is likely to be inconsequential. However, for the motorist making a steady progress around the edge of the city, this is likely to be where things get a little slower and a lot more confusing. Here the North Circular makes an abrupt ninety-degree turn to the right, crossing traffic from a couple of less major but still busy local roads. The mess of traffic lights, the confusion of signs, and the absolutely counter-intuitive oddness of this manoeuvre is explained by the very earliest plans for this route. Using a mix of purpose built new road and the existing pattern of streets, the plan was to form a designated route rather than a distinct, newly built path through the city. At points like this junction, the layout remains much as originally planned. There has been some work to divide flows of traffic, some clever work with traffic signals and priorities - but essentially, an urban motorway screeches into a Victorian crossroads here. I navigated the crossings carefully, picking my way from the north-western to south-eastern corner of the junction by instinct - there was little in the way of direction for pedestrians. The steady drizzle of rain had become a more sustained fall and I was aware I was getting rather wet. Bowes Road picked up the baton for the North Circular in somewhat more sensible style - becoming a broad urban dual-carriageway between a parade of local stores and the recognisable frontage of a long-disused cinema - The Enfield Ritz, now in the service of the local Jehova's Witnesses who to their credit appear to have done much to preserve the building. Beside me, a long development of new-build flats on what appeared to be the liquidated edge of a school playing field was being constructed. As I passed the show home, optimistic salesmen were setting out the signs for a day of being ignored by motorists. I noticed with some surprise that the upper decks of these small but otherwise decently built flats had balconies overlooking the A406. I wondered what odd, Ballardian mind had designed this building, knowing that on the best of British summer days, the view would be a distorted vista of the severe Board School buildings through a hydrocarbon-laced haze? I knew that this section of the walk would lead me to a number of areas which I'd recognise, and Powys Road soon interrupted my weighing up of how life here beside the road might be? I'd strayed a little along this street while searching for Pymmes Brook, finding a proud bridge parapet constructed for Southgate District Council in the midst of the fine suburban homes. I mentally assessed my position - once again the North Circular had appropriated the flat valley-bottom of the brook for its alignment. Up ahead, the Hertford Loop of the railway from Kings Cross passed overhead on a long, slewed bridge, the overhead wires sizzling quietly in the rain. Beyond the bridge a palisade fence marked the crossing of the New River under the road. I swerved through the narrow kissing gate and onto a muddy and litter-strewn path between the embankment of the railway and the river, emerging on the quiet grassy bank beside the water. There is something oddly tranquil about this waterway at any time, but having just escaped the tumult of traffic on the North Circular, it felt especially calming. Emerging from a utilitarian concrete culvert under the road via a litter-festooned debris trap, the river curved away to the northeast, crossing Pymmes Brook somewhere in the middle distance. I paused for a while, the rain was stopping and this seemed a fine place to wait it out for a moment. It was comforting to be connected to a part of London I knew better at last. While striking out into the unknown has its attractions, the sense of familiarity was welcome just now.

That feeling of being somewhere I knew fairly well persisted - the crossing of Green Lanes was one of the places I first remember needing to interact with the North Circular on my travels. Then it felt like an insurmountable barrier - an almost impassable point beyond which pedestrians weren't welcome. I thought back to those earlier walks as I picked my way across the tangle of crossings near Palmers Green Bus Garage, and set off again alongside what was now a busy four lane highway between more of the typical suburban dwellings which had lined the route since Chiswick. The road still curved elegantly along the valley of Pymmes Brook, crossing it via an inconspicuous metal bridge soon after the Green Lanes junction. The brook wound eastwards via Tile Kiln Lane - a quiet patch of nature reserve I'd walked before. This time I stuck to the road, most of my walk towards Great Cambridge Roundabout being along a service road separated from the traffic by a thick, thorny box hedge of the type beloved of Local Authorities everywhere. The spiny stems trapped the swirling litter and repelled sound, reducing the traffic noise to a dull rumble from the front rooms of the homes here. As I climbed up to the level of the tall red-brick arc of bookmakers, take-aways and letting agencies which ring the junction with the A10, I realised I'd need to head under road to get back on route. The subways here are confusing, poorly signed and a little unwelcoming - mostly because the cycle path fills most of the width of the passage, requiring pedestrians to hunch alongside the edges of the tunnels uncomfortably. The walls are clad in shades of brown and cream, betraying the vintage of the last reconstruction of this junction. In the midst of the roundabout, the North Circular passes beneath, a weird, echoing roar coming from the deep concrete channel in which the road reverberates. It was oddly compelling watching traffic surging along the road I'd been accompanying for so many miles, now businesslike, buried beneath the A10 - a sizeable and important road in itself, one of the impressive radial routes constructed in the 1920s - but it seems even these venerable byways must give way to the unstoppable North Circular. Beyond Great Cambridge junction, I'm on very familiar territory. Avoiding the trap of being lured onto Silver Street - the former route of the North Circular - I walk the narrow footpath beside the traffic once again. This is the least welcome I've felt as a pedestrian for some miles. The path feels inconsequential, littered with dirt and dust from the road, and hemmed in by a crash barrier. There is private green space beyond the fence, and within the tangle of allotments and gardens, Pymmes Brook still runs. I'd tried in vain to walk that way before and ended up here on the roadside. Up ahead, the layby was still the temporary home for a small community of Polish truckers who appeared to be engaged in a small cycle maintenance sideline too. I politely slalomed around their handiwork, passing under the sign which told me that I, along with any horse-drawn traffic, would be forbidden from walking along the road in a quarter of a mile. I wondered as I covered this short distance what was less common here - pedestrians or horses? I'd seen none of either since Great Cambridge Junction. The rather baleful buildings of the North Middlesex Hospital loomed over the road, and another unwelcoming subway passed under the road to reach it. Up ahead, the gantry signs flickered up a lane-closure as the road passed into tunnel under Edmonton. The traffic reacted by groaning to a sudden halt. Horns sounded back along the carriageway. I slipped gratefully into the relative calm of Pymmes Park. The road was ever present, but the tall railings, the algae carpeted pond and the unconcerned ducks nodding their way around the islands of reeds made for a less turbulent atmosphere. I picnicked absent-mindedly, wondering how far I should try to get today? Despite a sense of familiarity, the road seemed endless, all-encompassing and somewhat unfriendly here as I passed from North London into the East.

Reluctantly leaving my comfortable bench, I headed under the Overground near Silver Street station and crossed the chaos of Fore Street. The North Circular resurfaced from its brief subterranean section, and I was again alone on the pavement beside it. The busy tumble of businesses which straggled alongside since the crossroads soon petered out, and it was just me and the traffic once again. The skies widened in front of me as I approached the Lea Valley with only Scott House, a tall slab block to the south of the road, to interrupt the suddenly darkening skies. Another downpour was coming, and as I slogged along beside the road I noted a curious pair ahead: two young men, apparently Eastern European, and in pristine sportswear. They walked purposefully along beside the road, apparently checking the route on their 'phones, in bright white hooded tracksuits and spotless trainers. I wondered if I appeared as curious to them when they glanced over, suddenly aware of being followed? They stuck to the road, walking in the deserted cycleway beside the traffic, while I disappeared momentarily behind the fringe of trees to use an adjacent service road. At Kenninghall Junction they appeared again, navigating the crossings in front of the tired and disused buildings, and climbing the ramp to cross the viaduct ahead of me. I followed, wet and tired, but still possibly better attired for this walk than they were. The North Circular rose and began its snaking crossing of the Lea Valley. I spied Pymmes Brook for one last time, slipping under the road to emerge in the Ikea carpark. The almost entirely unused Angel Road station was below too, impossible to access easily and waiting time to be closed in favour of a new facility serving the emerging Meridian Water development. The site for this new district was now apparent: a broad brown smudge of empty land to the south - an area I remembered as a grimy but still busy industrial estate. When I'd last passed by it had been a mess of half-demolished buildings - now, nothing but carefully graded soil. I thought of the Olympic development on Stratford Marsh - how quickly life disappeared from the intriguing tangle of waterways and factories once the developers moved in. Meridian Water feels like an opportunistic off-shoot of that grand project. Can prosperity be persuaded to edge north along the Lea? That remains to be seen. The road bucked northwards, passing an unlikely banqueting venue and a beleaguered Premier Inn in the shadow of the reeking London Waste incinerator. The sickly smell of decay hung in the air as I crossed the Lea Navigation, taking a broad swing along the sliproads of the complex junction to rejoin the main route as it crossed the river and a flood relief channel. I spotted the pair of young men I'd been following beginning to double back along a footpath below me, heading for the towpath. Ahead of me a wooded hillside rose away from the valley. I'd made it across the strange industrial hinterland which had first drawn me to this part of the North Circular. I'd crossed the ancient boundary - in simpler times, this was Essex.

At the junction with Hall Lane, I pondered my progress. I'd started walking early and had time to spare with a later train home booked. I thought about my coming week of holiday - that in a couple of days I'd be back in Chingford briefly on route to Kent. I had the energy and time to press on, and time off to recover from a long walk. When I'd hastily planned these walks around the A406, I'd assumed I could cover the road in two evenly-balanced jaunts. But the hot weather and slow going on my first walk had meant I was picking up the slack today, and there was quite a distance yet to cover. This part of the road though, was very familiar indeed. The high brick wall concealing the Chingford Hall Estate soon gave way to the flank of the vast Sainsbury's near the remains of Walthamstow Stadium. Across the road were the reservoirs which lined the Lea Valley, and the strange marshy wasteland around Folly Lane. I felt oddly at home here. The road shuddered on, six lanes of traffic moving at speed towards Crooked Billet while pedestrians were relegated to walk along Walthamstow Avenue, divided from main road by the now familiar chainlink fence but still busy with traffic serving the industrial units lining the route. Again the North Circular descended into a tunnel under the complex junction, my own route leading to a dizzying spiral of footpaths and subways which burrowed under the roundabout, suspended between the surface and the roadway. The decoration and design of the complex suggested it was completed at the same time as the similar burrowing grade-separation at Great Cambridge Junction. I emerged at the end of Chingford Road, close by where I'd followed the path of the River Ching in the early part of the year. This time though, I was turning south, skirting the oddly makeshift Walthamstow Ambulance Station marooned between roads on the edge of the roundabout, and passing by Arsenal's youth academy and training ground at Hale End. My route here was the relatively sedate Wadham Road, a suburban feeder which was in fact the original North Circular here, which climbed to cross the railway and join the road from Highams Park. Across the street I could see the frankly terrifyingly named Living Flames Baptist Chuch, which I pretended an interest in while I secretly snapped a really badly designed road sign. A couple of locals, chatting beside the Star of India restaurant were clearly a little suspicious and I swiftly moved on. My route from here was unplanned and a little indeterminate. Looking ahead, the North Circular climbed a hill and disappeared between the trees of Epping Forest's southern reaches, a surprisingly impressive vista in the gloomy eastern sky. This relatively newly constructed section of road, built in an era when we were perhaps more aware of visual amenity but less inclined to manage environmental impacts, had been carefully concealed within a deep trench cut through the southern flank of the forest. Oddly, the original course of the road - a far less destructive curve south towards the A503 - had been entirely abandoned to nature and was now a broad grassy swathe on the edge of the forest. South of the road, the suburban streets seemed largely cut off from any useful path for some distance. While the map showed forest paths crossing under the road, they took me a long way south towards Walthamstow, considerably adding to my route. Spotting the potential signature of a makeshift path running parallel to the road, I decided to find a way in by climbing the steep rise of the rather wonderfully named Sky Peals Road. At the brow of the hill I found an unmarked muddy entrance to the woodland and I plunged in.

I'd been oddly nervous about this part of the walk. While I loved walking in the forest, I knew that by now I'd be both tired and keen to find a swift path through the woods. The lack of any clear route at first was disorienting, and I had to navigate carefully via my map to ensure I was heading generally in the direction of the road. Soon though, the sound of traffic cut through the thick woodland, and I spied the tall green early warning sign for Waterworks Corner peeking between the trees. Sure enough a narrow nettle-lined path paralleled the road, winding between clearings and climbing gradually. Now I had my bearings, I was able to enjoy this part of the walk more than I'd anticipated. While it was true I was just passing through today and wouldn't be here nearly long enough to enjoy the cool and quiet, there were as always some surprises to be had. My first came when I crashed out of the trees and onto a broad gravel path running roughly north-south. Beside me was the footbridge over the North Circular which I'd crossed on route through the forest months ago. I ventured onto the bridge and took photographs of the road pulsating with traffic below. It seemed so different up here, quite different from the gentle swish of cars masked by trees on the forest path. Retracing my steps I found the continuation of my path - an overgrown gully between trees which I'd imagined I'd never need to, or perhaps even dare to walk when I last passed this spot. Suddenly these minor side-paths, tributaries of the official way, had become my target. Perversely, it took the act of following a huge, tarmac-covered monstrosity to uncover their purpose and route. I crashed back into the woods, the path turning to skirt a deep bowl in the ground. I realised that down there, somewhere was the circle of bridleways around Waterworks Corner which I'd navigated at the end of the A503 walk. I slithered down a leaf-littered bank. It was, at least, almost dry now - a far cry from the swamp I'd picked my way around last winter. The urge to head north or south here, to follow the forest path rather than the road, was very strong. But I was close to a decision point - the next stretch of walking on a side-road high above the carriageway would bring me to Woodford. At that point, once again, I'd have to decide what to do next.

I sat for a while on the low wall surrounding a litter-strewn planter in the garden which sits above the North Circular. The wide bridge, in its attempts to conceal the road beneath, had been developed into a plaza. Few people stopped here - the fumes rising from below or the unnatural hum of traffic permeating their thoughts seemed to put them off. I'd been alone with my own thoughts for a few minutes, calculating and recalibrating. I wasn't really sure where - or how - the walk should end. After this stop, all the possible points at which I could leave the road felt remote and complicated by onward travel arrangements. I could call it quits here, head for the city and loaf around for hours being lazy. Or I could press on. Eventually, curiosity overcame me. The same strange urge which had been largely responsible for this walk in the first place: across the street was Rookery Path. This narrow alleyway, sidling along the edge of the chasm in which the North Circular runs and carefully carrying people away from Waitrose, was apparently important enough to bear its own street name. Naming pathways wasn't usual practice in Redbridge - and seemed to indicate some provenance. How long had this route existed? How far did it go? I needed to find out. And so I found myself walking steeply down hill on a narrow path. Descents are not my thing at all - while climbing is lung-burstingly hard work and exhausting on the knees, heading down requires a degree of balance and the ability to defy momentum. Two things I struggle to maintain even at my best. Added into the equation was a procession of cyclists, apparently determined to cycle up the hill as a feat of bravery or stamina. They swayed along, their machines swaggering haphazardly beneath them as they leant all of their weight and power onto the pedals, huffing, grimacing and staring resolutely at a spot inches ahead of their front wheel. I dodged and weaved, trying to stay standing and out of the path of passing cycles. Eventually, the path bottomed out beside the road, sandwiched between a massive concrete wall and more of the sturdy, grime-streaked chainlink. The road felt just inches away, and another of the rather sobering sprigs of browning flowers marked the spot where it had claimed another casualty. A sign urged pedestrians not to cross here at this 'accident spot'. The only way was forward - passing more signs reminding me this was Rookery Path. There are few mentions of Rookery Path besides what appears to be the news report of the incident commemorated by the flowers I'd seen - but it appears that The Rookery was one of two sizeable and ancient estates divided by George Lane, which now forms the main shopping street of South Woodford. This path appears to have no great pedigree - the 1923 Ministry of Transport map shows nothing aside from whitespace, while later maps chart the proposed route of the Woodford Spur road scything across open countryside, heading for the Roding Valley. Now the re-routed course of this road is buried under the A406 as it curves gently southwards, concrete ramps ascending to take the beginnings of the M11 high over Charlie Brown's roundabout. My footpath edged around the junction, connecting the ends of cul-de-sacs formed by the interruption of this landscape of overbridges and viaducts. I'm eventually committed to a slightly perilous crossing of Chigwell Road in order to duck under the wooden arch marking the Roding Valley Park. Once again, I'm on familiar ground.

Ducking under the pylons and emerging from the tangle of ramps and bridges, it was good to find the River Roding again. This proud little waterway, having made its way from rural Essex, was now filled with a swaying forest of green weeds. My path skirted the river, hugging its straightened course southwards. Once it had meandered along this valley, swerving crazily to the sides of the green bottom. It seemed likely that the building of this relatively modern section of the A406 had put paid to this, eating up a significant part of the western edge of the meads through which the river had trickled. My path was sandwiched between river and road, a deep green tunnel in the summer, and a pleasant bit of off road walking. My feet were tired and the sun had beaten back the clouds, making for a much warmer afternoon. Surprisingly, I didn't see another soul out here in the valley at all. Beyond the line of tall trees, the road hummed and shimmered in the heat, traffic hammering along this final, fast stretch of the road as it turned directly south and like the Roding, headed for the Thames. I recalled my Roding Valley walks, and knew that this stretch though not long, would see me isolated from the road for quite a distance. I was never quite free of its gravity though, nor of its sounds. A bird of prey swooped onto the grassy riverbank, unconcerned with the nearby tumult of traffic. Eventually I reached the point where I'd turned aside to follow the river under the road on my previous walk, instead climbing a curving bridge to the eastern bank. I silently begged the gate to be open - so many other routes into this valley seemed to be locked and forbidden for some reason. This time I was lucky, and a rather tiring but thankful clamber up some makeshift steps deposited me a little way from Redbridge Roundabout. I trudged past a Premier Inn and an associated Beefeater restaurant, apparently named for Redbridge House, a curious nearby property of some vintage now divided into ludicrously expensive luxury flats. As I passed the elegant rotunda and tower of Charles Holden's Redbridge Station, I cursed my fear of escalators and pressed on - one last tiled underpass taking me under the A12 as the North Circular strode above on a viaduct. Eastern Avenue continued out of the city, another of the broad and straight arterial routes from the 1920s - the same road-building frenzy which had given us the earliest form of the A406. It's western course here had it's genesis in an altogether different era, being the eastern end of the controversial M11 link road. I climbed slowly onto Woodford Park Road, the long suburban street which paralleled the A406 from here into Ilford. When I was last here, it was a litter-strewn, fly-tipped mess of a street, the rather fine semi-detached homes looking out over a footpath teeming with filth and rubble. Now it was tidier, newly erected signs warning of the considerable penalties for leaving waste. As I passed by on what was now a sunny afternoon, families went about their day - cars were washed, visitors arrived, delivery vans shuttled up and down the street. Behind the houses, a narrow strip of green separated them from the North Circular, slowing to a halt as traffic for Ilford and for the A13 beyond attempted to disentangle itself into the correct lanes. Woodford Park Road seemed endless - I passed the bridge where I'd left it to cross the valley last time and walked on. The house numbers seemed to decrease almost imperceptibly. I was dog-tired, the dirt and dust of the road covered me and the chemical-heavy air I'd been breathing for felt insufficient and overheated. The row of houses continued endlessly ahead. Beyond were the jagged glass towers which signified central Ilford and a sensible place to end the walk. I'd never tried to pretend this trek wasn't going to be a challenge - but I was surprised how exhausting walking beside the endless churn of noise and traffic would be.

I turned a corner to find a welcome site - the York Road entrance to Ilford Station, refurbished in 2016 and now accessed via an attractive former Great Eastern Railway building rescued from seeing out its days as a store-room and works office. As I found my way to the platform for a train back to London, I looked west towards the viaduct carrying the North Circular for its last few miles south. I knew the route well, having picked my way along the valley several times before on various walks. I knew too, that it was almost impossible to walk close to the road here. Somehow I'd have to cover these last few miles to the river - and beyond, to the South Circular which I'd briefly connected with at the start of this walk in Chiswick. Connecting that missing link felt important - because this second day of walking on the North Circular had been almost entirely about making connections with previous walks. As I've mapped the north and east of London, I've made these often unexpected links which have only deepened my sense of how mysterious and intriguing these zones are. What seem on the face of it to be somewhat benign, self-effacing suburbs hide the history of ancient manors, lunatic asylums and vast primordial forests. London conceals all of these things, but it only takes a walk to scratch this surface. As the train creaked to a halt and the doors opened in front of me I wondered at how many times I'd passed along this route - over the very same rivers and under roads which I was now walking? Life has taken surprising turns and led me to unexpected changes in recent years, but this landscape has provided a constant backdrop, its complexity emerging slowly as I walked, read, and understood the territory a little better over time. The river beckoned, and beyond it the unknown south. I'm not sure I'd fully figured out everything I'd learned from navigating the North Circular - but still, this walk was far from finished.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here. You can also read about the first part of this walk.

The second half of the twentieth century was a rather remarkable time in Britain. All of the assumptions about town and country, the way of life which went on in each, and the kind of people who inhabited them were somewhat up-for-grabs for the first time since the Industrial Revolution. It was also a surprisingly exciting time for planners and architects, professions who rarely enter the general public discourse except when they do something very wrong indeed. The massive destruction of city centres in the second world war, coupled with a municipal spirit which genuinely sought to improve conditions for the vast populations still effectively living in Victorian slums meant new responses to how people were housed and how their needs were met. In fact, for perhaps the first time since the pioneering efforts of industrialists like Titus Salt or Lord Leverhulme, the concept of placemaking - creating spaces deliberately to be inhabited - became a preoccupation for local and national government alike. In his second book broadly focusing on this period, John Grindrod has used one of the 'big ideas' of the era as a lens through which to view this period. Was this a golden age realised, or good intentions squandered? Through the course of Grindrod's own connection with the green belt around London he tries to determine the outcome.

John Grindrod did most of his growing up on the very edge of New Addington, where urban Croydon finally stops trying, and Surrey begins. He describes this edgeland world in fond but honest detail throughout Outskirts as he traces the thread of the idea of a green belt - initially around the ominously expanding fringe of post-war London. On his journey, Grindrod examines the origins of the idea in the Garden City movement who proposed the rigorous management of space and density within their tightly zoned new communities, and attempts to untangle the politics of planning for the swathes of unused and unusable land around our cities. One of his early discoveries, and a persistent theme throughout the book, is the lack of greenery in the green belt - while his own upbringing on the edge of the downs was relatively bucolic, the green belt elsewhere contains the kind of edgeland industries, waste management facilities and abandoned land which is probably depressingly familiar to drivers everywhere - and which not coincidentally fill the photo galleries of this blog! It soon appears that in fact, virtually anything can be built in the green belt once the requisite hoops have been jumped through - except housing. But of all the pervasive, permitted development which Grindrod finds, it is the golf course which is most prevalent. These cartoonishly green swathes of primped grass and fluttering flags litter the edges of our cities, destroying the very ancient countryside which the zones would seem to be designed to protect. Of all the promises of Class War which the late 1970s seemed pregnant with, it seems it's the war of the golfing versus non-golfing middle classes which is playing out even now on the edgelands!

And this leads to another revelation for Grindrod - that the green belt has very little to do with protecting the countryside, and everything to do with protecting life in the city. The designated swathes of space, by the 1960s enveloping many English towns and cities, aimed to check the growth of the towns and to preserve the distinct identities of places which otherwise threatened to merge. The green belt was also where the overspill towns would be placed - those new towns which would house the displaced from the rezoned and yet-to-be revitalised city centres. These towns were rarely entirely new - often co-opting existing communities like Old Harlow or the villages around what is now Milton Keynes - but their position squarely within the belt allowed total control over their growth, their zoning and their density. I grew up amidst one of the later phases of the New Towns programme - in Redditch, Worcestershire - which suffered greatly when the programme was finally cancelled in the 1970s before much of the work was complete. Among the gravel-covered empty lots redesignated as pay-and-display carparks, one redeeming feature of the plan was the swathe of greenery which one needed to cross to get to Birmingham. From my earliest interest in maps and roads, I understood that the town and the city were never to meet.

This could all be another dry examination of the successes and mishits of planning policy but for two things: firstly, John Grindrod writes with a wit and clarity which turns a wander through the wooded edges of Croydon into a minor epic, and a trek through the history of planning into a historical romance. His tackling of the social and political themes from which the green belt arises are sensitive and give appropriate credence to the tenor of the times. We'd never accept such paternalistic interference nowadays of course, in this post-expert era of history - but Grindrod manages to put us back in the shoes of those principled and ambitious post-war planners who really wanted to create a new Britain from the ashes. Secondly, the story is riven by an autobiographical strand which describes a family life that many of us who grew up at that time will recognise - the social engagements, the attitudes and expectations, and the pressures of being young and different were certainly not lost on me. The relationship of family, place and policy somehow came to a head in those years during the 60s and 70s when anything seemed possible despite only having four TV channels and living miles from anywhere.

Outskirts manages to be a funny, affectingly personal history of life in a particular setting at a particular time, whilst successfully unravelling the decisions and policies which created that way of living. Once again, John Grindrod has chosen a topic which for many would seem unsympathetic and without interest, and turned it into a rather joyous book.

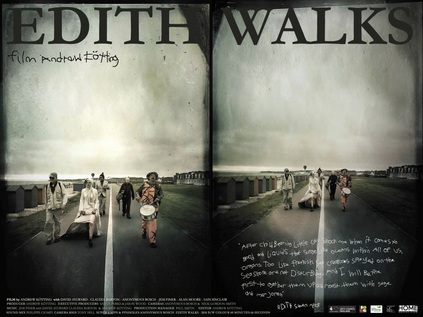

There is something rather special about one of Andrew Kötting's sometimes improbably odd film projects making it to completion, let alone a cinematic release. Getting to see one during its debut tour of British cinemas felt even more of a scoop - and I'd looked forward to this for some time. Coming at the end of a really quite troublesome and wearying week, and directly before I headed off on a summer holiday, it took on a further significance - it was, after all, a film about a journey. So we settled into the comfortable seats of Bristol's Watershed, realising that we made up a solid two-thirds of the audience. It was, almost, a private screening tonight.

Edith Walks has something in common with the majority of Andrew Kötting's previous long-form films - in that its sense of pilgrimage is almost all that holds its fragile elements together. This trek, just over 100 miles in total, attempts to create an as-the-crow-flies connection between Waltham Abbey - the last resting place of King Harold - and St. Leonards on Sea where his likeness is captured in a statue. In the sculpture, Edith Swan-Neck his handfast wife lifts the King's head tenderly from the battlefield at Hastings, recording both the moment he is discovered and that at which he is confirmed to be dead. At that moment, Harold slips from history into mythology - the story is written into every school history book, but the man slips wholly out of sight. The history goes that after Edith's discovery of the King on the field of defeat, he was segmented and parts sent to religious houses throughout the land. Finally his heart was taken to Waltham Abbey and buried. This walk, with six companions making up a clattering, chattering tribe to accompany Kötting and Claudia Barton as 'Edith', attempts to link Edith back to Harold - a reunification after 950 long years of separation - King and Queen reconnected, and man and myth made good.

The six companions are an interesting bunch in their own right - along with 'Edith', musician Jem Finer hauls a complex recording device that creates and receives sound as he walks - often the sounds provided by David Aylward, a percussionist who improvises his art marking time along the route. Pinhole photographer Anonymous Bosch captures events as they occur, while Iain Sinclair provides the closely-read mythological underpinnings for the story, sometimes bouncing his ideas against Alan Moore, the Seer of Northampton, who links deeper into the odd English Gothic. In Moore's telling, Harold never dies but becomes wholly subsumed into the myth - becoming Hereward the Wake, our first freedom fighter. Along the way, Barton sings - her remarkable torch songs providing a haunting voice for Edith which is entirely lost from the official account. As the companions progress along the Lea Valley, under the Thames at Greenwich and into Kent, their interactions with modern-day England form the narrative course of the movie. No-one quite knows what to make of them, and fewer still seem to fully understand their purpose. Such are the films that Andrew Kötting makes - miniature, absurd epics that mess endlessly with chronology, mythology and psychology in order to spin out a fable. If he has a message for the viewer it seems to be that you should believe nothing which you see, and even less of what you hear. Kötting's occasional background appearances, foolscap firmly pull onto his reassuringly solid, square head as he regards the antics of his companions are reassuring. There's someone else seeing this - it's not a dream after all.

Kötting's role in these films has always been a little unclear to me. Is he playing The Fool as a character - there to provide a foil to the incredibly erudite discussions that Iain Sinclair and Alan Moore share with 'Edith'? Or perhaps he's just there to orchestrate things - to deal with the unwelcome Police interest in Greenwich, or to corral the impossible troupe as it makes steady southbound progress? What he certainly seems to function as is a catalyst - it will be Kötting who decides to film a bow scraping at a bicycle spoke belonging to a bemused bypasser, or who instigates a conversation with Sinclair which delves into new theories and possibilities of the Harold/Hereward myth. The camera rolls, and there he is again in the background, grinning in encouragement. The architect of a particularly English sort of chaos. As Iain Sinclair has observed elsewhere, walking with others provokes story-telling and changes the dynamic of conversation. There's an almost Chaucerian element to the tales shared by the six as they progress south towards the provisional site of the battlefield, historical events represented by found footage of a 1966 school re-enactment of the battle.

The audience response to Andrew Kötting's films is often as varied, confounding and challenging as the work itself - and while I left the cinema amused and enlightened with a head full of reference points to review and research, my wife - a far more engaged cinema fan with a solid grounding in classic movies over the years - was genuinely enraged. She couldn't see a purpose beyond self-aggrandisement - but what sense was that if no-one was watching? We discussed the film and our various reactions for much of the journey home, and while her view softened somewhat she remained confused and irritated by Edith Walks and it's lack of narrative and deliberately obtuse and sometimes amateurish cinematography. For my part, I'm probably just as confused in many ways - but the playful oddness, the eccentric rewiring of history by way of a walk and the unwinding of a new mythology along the way absolutely appealed to me. Mark Kermode suggested in his own review of Edith Walks that as long as Andrew Kötting exists, all will be well for British filmmaking. It's a tough mantle to assume, and one I suspect Kötting might utterly refuse to bear - but I tend to agree that while he continues to act as documentarian and catalyst to these odd, location-specific pieces, there is much to be optimistic about after all.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.