A Walk in the Park - On the trail of Pymmes Brook

Posted in London on Saturday 6th August 2016 at 11:08pm

It's a long time since I visited Cockfosters...

My solitary previous excursion even predates the records I've kept on this venerable website. Back then I have a hazy memory of emerging from Charles Holden's low-slung, futurist station building to find a solitary row of tall redbrick shopfronts across a busy road. In my recollection, there were newsagents, laundrettes, a Chinese takeaway - the familiar constituents of countless similar ranges of small, local stores across the suburbs of London. I'm not sure if that was the exact mix of premises or whether I've projected the many hundreds of similar ranges of district shops I've seen since onto unlucky Cockfosters? I recall on that visit sensing something I'd later learn to call 'range anxiety' - the sense of being at the end of London was new and strange. There was too much to left to discover in the centre of the city back then, and with the line inked carefully into my Baker Rail Atlas I was soon off again, plunging back under the earth and into the city I was slowly growing to understand. I already had my secret haunts, my customs, my comfortable corners, and the chilly heights of the ridge shared by Middlesex and Hertfordshire could wait. In the event they waited about twenty years and a lot had changed at Cockfosters in the interim. The station was still the sleek, concrete-ribbed structure I remembered, nestling in a hollow beside the road like the skeleton of a prehistoric beast. It echoed the similar construction seen in the line's western terminus at Uxbridge - but it was grounded, purposeful - somehow less lofty and less deliberately architectural. Cockfosters station nestled neatly into its site, leaving a clear view across the heights. Following the rather charming 1950s vintage signage, I took the subway under the road and emerged in the pleasingly curved shelter which echoes the profile of the main station building . The red brick wall of shops loomed above me as expected - but oddly it had changed! The metal shutters of off-duty off licenses had been replaced by a capacious double-fronted café where people enjoyed equally impressive breakfast platters. A greek restaurant owner started his day by hosing down the footpath and watering hanging baskets dividing his inviting looking premises from a local whole-food market. The summery weather had brought people onto the pavement tables - expensive sportswear and jewellery hung from their tanned frames while their Porsches ticked in the heat. Cockfosters was looking east - aspiring to be the Essex suburbs over the ridge, rather than the more serious and genteel hamlets of North London. I felt out-of-place, but entirely unseen - because I didn't fit, they couldn't detect me. I ambled towards the Co-op and purchased plenty of water. It was already well over 25 degrees and getting warmer. My walk felt suddenly ambitious and the charms of this curious knot of civilisation seemed more attractive. The spattering skillets of sausage and vine-ripened tomatoes thudded satisfyingly on the table, the jug of inky black coffee was whisked away for replenishment. Summoning resolve I turned west - again, against every instinct - and approached the attractive honey coloured parish church. Chalk Lane wound around a knot of impressively large homes, and I realised I'd not understood just how suburban this area was before. I'd always written it off as some sort of aborted Metroland outpost, empty fields and aborted ambitions beyond the fringes of polite society. The provinces, perhaps. In fact it owed more to the Essex suburbs with their conspicuous evidence of wealth and consumption - the gated drives and electric doors were identical, the 'protected by...' security signs read the same way. But things were more restrained and sober here. The houses gave nothing away. They looked inwards, protecting rather than advertising their inhabitants' affluence. Soon the lane became decidedly rural as it passed the conjoined bowling, football and cricket clubs, and I turned west again onto the appropriately named Games Lane. This led me onto the fringe of Monkton Hadley Common - a swathe of impressively dense and ancient woodland which soon enveloped me in its cool, green canopy. I never felt totally isolated of course - the gables of nearby villas often intruded on my vision - but it was pleasant to walk under the trees. Lost in the woods, it was a surprise to spot a small brick bridge at the top of a rise ahead - there was Pymmes Brook, trickling earnestly south. I'd encountered my target early - and I first had to follow the rise of the land beside it to the sluice at Jack's Lake where it unceremoniously dribbled over a concrete beam into the channel below. Here was the source of that sluggish, reeking ditch I'd come upon in the Lea Valley many times. Clear and cool, energetically determined to reach its destination, mercifully unaware of the fate that awaited it.

I recorded the source in a picture for posterity, and set off south alongside the brook. The smooth, root-bound woodland floor sloped down into the water, making it possible to walk close beside the merry flow - a rare pleasure for a London waterway. Soon though I was directed down a suburban footpath and the woods gave way to housing: two long streets of decent sized homes marching down the valley with Pymmes Brook dribbling between them in the middle of a green central reservation. The brook's course was unmistakably marked by trees and tall grasses. At the mid-point of the avenue a small concrete bridge crossed the brook. I continued south, taking the western side as it offered a route closest to the brook once I got to the foot of the hill. Here the brook disappeared under a solid brick bridge, and I was forced to detour even further to the west, climbing a hill and turning south again knowing the brook was behind a line of semi-detached houses which arced across the hilltop. As I walked the curve of the aptly named Crescent Road and dodged the rubbish truck which was lazily but aromatically plying the street, I caught occasional glimpses into back gardens framed by tall trees and deep reed beds - tell-tale signs of the waterway. At the crossing of Margaret Road I saw a woman in a livid pink dress sorting through a bag of books left out on a low wall by the householder. As I approached she tapped me on the shoulder and said "let's find you something blokey - what about this?" as she thrust a novel at me. The cover was all rusted ironwork with the text securely riveted onto the front and the authors' name dwarfing the title. It didn't appeal and I guess my face gave away my lack of interest as she began to vigorously sort through the pile again. By now the householder was out with handy carrier bags if we wanted to take the books off her hands. "James Bond!" - a slim volume was jabbed at me and I instinctively accepted it. Satisfied that she'd found me something, she returned to combing through the books for more nuggets of interest. Unsure how to end this transaction I commented on the weather and what a good idea the passing on of unwanted books was, before uncomfortably shuffling on my way. I paused at the next junction to look over the parapet of a bridge discreetly nestled between garden sheds and garages. The brook lay deep beneath, wider and swifter now it had been joined by the Shirebourne whilst it wound behind the houses.

Turning east onto the appropriately named Brookhill Road, I noted the ground rising again to the ridge on which Cockfosters sits - and if I continued this way, I'd find my way back to my starting point. I crossed the brook again here at an acute angle where it passed behind a small range of shuttered local shops. Beyond an untidy triangle of fly-tipped builder's rubble it disappeared once again under East Barnet - a settlement I confess to having never considered before. I turned onto the curiously named Cat Hill and noted the steady downhill progress - I was heading into the valley which the brook had carved over the millennia, still on the trail. From what I could see on reaching the bottom of the valley, East Barnet was a busy urban centre: a war memorial, a branch of Costa, a range of takeaways, and an automatic public convenience which was frustratingly out of service. I felt a little guilty for my initial impression based on a stretch of tired, closed computer repair shops. My route turned south here shortly before I reached the well-tended rose garden which fronted the stubby Celtic memorial cross, taking me onto Brookside. The waters of the brook reappeared, meandering along the bottom of a broad valley with green slopes rising on both sides. I walked on the grass, grateful for softer going underfoot, and tried to discern the curve of the brook at the foot of the valley in its green tangle. On the adjacent slope where the official path ran, a busy road rumbled along the ridge and the sun glinted from passing car windows. I was content with my off-road progress along this fine green swathe which finally opened out into Oak Hill Park - a broad and open plain in the midst of the suburban sprawl which had attracted the locals on this sunny morning. I found a vacant bench and sat beside the still clear and lively brook while I refreshed my water-bottle and rested my feet. I'd worried this walk might be just too suburban and uneventful, but the mix of geographical detective work and pleasant surroundings was just the tonic I needed today. Before leaving the park I detoured onto the west bank of the brook and walked along the rear veranda of a sizeable and dilapidated block of changing rooms in an attempt to use another of the London Borough of Barnet's public conveniences - but again, it was closed. Austerity bites in the oddest ways, I suppose. I trudged on, out of the park and into another well-tended grassy division between avenues of houses. East and West Walk flanked the brook as it made a slow southerly turn towards Brunswick Park - the next in a chain of green spaces which shadow the route of Pymmes Brook through Barnet. Here the trail is additionally dubbed Waterfall Walk, reflecting the regular man-made concrete dams which cross the brook, slowing its progress and restraining it from overwhelming its banks in times of flood - something the brook has regularly attempted over the centuries. The barriers made for a pleasant plashing sound as the water trickled lazily over each one. I clocked the temperature at 27 degrees, and despite my public convenience predicament, the sound of running water was a welcome psychosomatic coolant. A long stretch of old woodland soon enveloped the path again, the tree line to the west discreetly masking the transition from Brunswick Park into the austere circles of New Southgate Cemetery. Embedded deep in this woodland channel it was easy to imagine the trees forming an ancient forest - but they in fact run tightly along the path, with the back gardens of Barnet never more than a few feet away. The only tell-tale sign of humanity on this apparently lightly-used stretch was the reek of a sewer which is laid under the path and which seemed on the strength of it's detectable protests, to be tested to its limits just now. Strangely, the brook and its shadow path remained quietly and entirely disconnected from the suburbs which surround them. I savoured the cool after the strong sun in the open park.

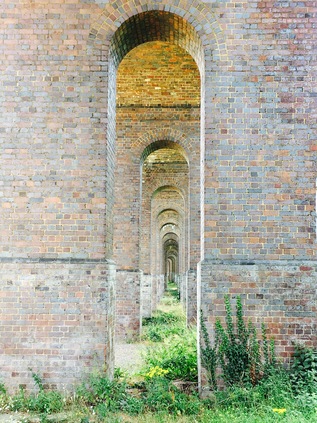

Rather unexpectedly at a sharp turn in the path a steel bridge deck appeared between the trees, with solid brick abutments swinging across the brook. Crossing a busy road under the bridge I found myself deposited at the foot of the great arches of Arnos Park Viaduct - one of the highlights of this walked I'd looked forward to, but hadn't expected to come across so suddenly. The northern extension of the Piccadilly Line in the 1930s posed challenges here - the Pymmes Brook carves a deep valley between the high ground of Finchley to the west and Southgate to the east - meaning that trains head north from the city in a deep tunnel before bursting into the open almost directly onto the ridge over the valley. The result are the elegant thirty-four arches of the viaduct which swings over the edge of the park. Underneath all this engineering effort, the still tiny brook which has miraculously worn this deep valley is canalised to dog-leg under the arches and continue its course to the south-east. It was a rare pleasure to get this close to such a magnificent structure and to be able to wander alone under the arches with the trains rattling overhead. Between trains, the silence along with the coruscating brindle pattern of red and blue brick made for a strange ambience beneath the arches. In the middle of each span, a central channel of tall and narrow arches runs the length of the viaduct giving a truly dizzying receding perspective. It was tempting to stride ahead, passing all the way along this secret inner path, until I realised that the deep concrete culvert abruptly divides the way, turning Pymmes Brook through two right-angles to continue a path through Arnos Park. I noticed that people didn't linger in the shadow of the viaduct and I had this stretch of path largely to myself. It was a shock then to move into the brighter part of the park and to find it teeming with families enjoying the sunshine and older folk contentedly occupying benches. I found my own bench and rested again, thinking about my lack of planning, and wondering quite how I could finish this walk?

Reluctantly leaving the park I was aware I was closing in on an old foe - the North Circular. This road has haunted my recent walks: blocking my way across otherwise open land and twisting into complex geometries which make pedestrian navigation impossible. Today though I was encountering the A406 in a formative state. Despite being improved to a grade-separated motorway from Finchley to Palmers Green, as it turns an abrupt right-angle here it degrades into a classic 1930s arterial with side streets and traffic lights. Semi-detached houses line the route on both sides, as traffic howls along avoiding the very suburbs they carve through. As is often the case, the road didn't travel alone, its course following the shallow valley of the Bounds Green Brook which joined Pymmes Brook near the park exit, masked by trees. Delaying my time on the road for as long as I could, I slipped across Wilmer Way to inspect the low concrete parapet of the bridge taking the Brook under the road, emblazoned with a proud but long obsolete Southgate District Council monogram. By following the quiet suburbia of Ashridge Gardens I could echo the course of the waterway until the road turned sharply north along Broomfield Avenue. In the tight elbow of this junction, a gap in the fence let me see the brook trickling along. I slipped my camera between the palings of the fence before realising that nearby a family were playing in their back garden and were regarding my presence with some horror. I quickly slipped my camera away and smiled - in the hope that this would belie the idea that the wild-haired, red faced man at the fence was some sort of prowler. Not daring to look back just yet, I scurried off up the hill and over the railway bridge. Pausing to look along the tracks to the south the sky-scraping antenna of Alexandra Palace recalled an earlier walk and suddenly things slipped into context - this walk was the missing link between the Northern Heights, the regeneration zone of Woodberry Down and my obsession with the Lea Valley. North London, turning on a hinge in the A406 felt connected and legible. At last that vast sweep of suburbs - each with its village centre and run of local shops, each with a hinterland of semis and hidden waterways - was locked into place. Maybe it was the sun, or the heat playing with perception - but I realised that the web of streams which had oddly attracted me to these environs linked into a wider system which described the topography of the north and east, drawing me into further explorations. I'd often stumbled over an answer to the question "why walk those areas?" because I really didn't know. It was an exhilarating discovery that there really was a pattern - and that this walk did, after all, fit into it. I celebrated my moment of discovery in the only fitting way - by detouring into a nearby Morrisons to finally use the conveniences and to grab refreshments. It was an odd place for an epiphany - but a supermarket in Palmers Green is as good as anywhere.

Once refreshed and underway again, I realised that I might have to adjust the scope of this walk - it was well over thirty degrees now and the sun showed no sign of moving from directly overhead. The next part of the trip would be challenging - but the walk was to yield a further special moment here, just beyond the impressive modernist hulk of Palmers Green Library. As I briefly turned into Green Lanes, the long stretch of road which runs deep into London's heart, I crossed the New River. Having stumbled on this quiet, stately presence in Barnet many years ago, found it circling the reservoirs at Woodberry Down and getting to explore its outfall in Islington it was rather special to look along the greenish, silent way and to imagine the long course to its source in Hertfordshire. Never meant to be navigable, the surface of the water shimmered tantalisingly close - just inches from the deck of the bridge. Resisting a strong temptation to turn aside and walk the river back to London, I returned to the crossroads, crossing the New River again as it continued north and east fringed by an inviting green towpath. Instead, I finally had to succumb to the North Circular, meeting it at a confusing confluence of suburban side-road and filling station, with traffic crazily queuing in zig-zags to leave and rejoin the carriageway. The heat radiated from the road and the metallic skins of passing cars rhythmically flashed the sun directly at me. I ducked my head and pressed on along the shared use path, the only pedestrian in sight. I wasn't sorry to reach a subway which permitted me to duck under the shuddering, overheated road to reach Chequers Way home to the vast Arla Foods dairy production site. The brook fringed the edge of the factory, and I was once again able to walk close beside it on Tile Kiln Lane. Considering the proximity of the orbital road and the factory, the walk here felt like a silent stroll along a narrow country lane. Beyond the low rise new-build flats at the end of the road I could head into a football field or pass the faded interpretation panels into the Tile Kiln Lane Open Space. I took the latter route - disappearing deep between high grasses and elderly trees, skirting the sports field and leading back to the main road at Great Cambridge Junction. The footpath was littered and cracked by roots - evidence of a slow return to nature. Bursting out of the greenery into a complex network of subways slung under the roundabout but above the road, I left the brook as it disappeared into a broad, concrete culvert to take a turn around the southern quadrants of the roundabout as I surfaced at the north eastern extremity on Kendal Parade. A fairly down-at-heel run of shops edged around the corner block. This was once an important stop on the highway, but was now passed at speed by all but a few - and they seemed to be lingering outside without purpose, soaking up heat and radiating boredom. North and south, the arrow-straight A10 headed from Cambridge into the city, a road usurped by new Motorways and better retail opportunities, while these local denizens watched and waited. The circus felt strangely trapped in time - a ringway-era relic which even the North Circular now bypassed by diving underneath. It wasn't a pleasant spot and I soon shuffled on swiftly in search of the course of the Pymmes Brook once again. It was here that I made my only real misjudgement in terms of today's route. Confused by what appeared to be access through the Millfield Arts Centre, I struck off along Silver Street at some pace. Soon after passing the gates of the sizeable property operated by Enfield Council I realised I was on the wrong track - and a desperate diversion into a small close of flats and houses gained nothing but curious and suspicious looks from the locals. As luck would have it, an elegantly dressed woman clip-clopped out of a nearby house in a businesslike fashion towards a very expensive car which diverted their attention briefly. They mentally checked her - plain clothes police? Insurance? Doctor? Meanwhile, the brook sat behind a locked gate opened only by a residents key. I had to retrace my steps to the North Circular.

Almost as soon as I started walking the treacherously cracked path at the edge of the road the warning that no pedestrians could proceed beyond the next quarter-mile was signalled by a huge green sign. I approached a lay-by where a Polish registered truck was parked, its owner sitting out on the grass in the sunshine. Suddenly a grinding and gasping sound announced the passing of a Jaguar saloon with smoke gushing from under the bonnet. He scuttered to a halt in the lay-by just a little shy of the truck and immediately began punching buttons on his 'phone. The trucker dashed around waving his arms and warning him not to open the bonnet. I passed by watching the strange scene and wondering just how I was going to escape from the road myself? Across the six lanes of traffic, the North Middlesex Hospital glowered over Edmonton - a grim and formless building. Unexpectedly, I found Tanners End Lane - a stopped up road severed from the A406 by solid bollards, and which would take me back to the Brook. In the event, I found myself almost where I'd have been had I pursued my original course on Silver Street, finding a paved slope leading down to a walkway deep between jagged, modern brick housing blocks. It was cool and shaded down here, the brook in its wide concrete channel. Up ahead, the channel divided into two, separated by a central beam which I recalled seeing at the outflow into the River Lea - though I've never established why this was done? There was some way to go for Pymmes Brook but much of it would be underground from here. The culvert loomed, broken tree-limbs trapped across the entrance. I climbed the ramp to Silver Street and into Pymmes Park - named from the brook which barely skirted its edge. I rested a while here, the sun still bearing down on the parched park. I could press on into Tottenham and try to delve for the brook under industrial sites and Ikea carparks, or I could call it quits at Fore Street - knowing the brook was bubbling under the junction on route to the Lea. Eventually I opted for the latter. It left a section of the route unwalked - but it was a troublesome and contested section which needed my wits and enough energy to manage the frustration of blocked routes and wasted turns. I had neither about me. The closest I could get to the route without walking was a bus along Fore Street and into the city, so I passed by Silver Street station and emerged at the crossroads where the North Circular emerged from the brief tunnel to make its arc over the Lea Valley. Edmonton was clinging to life via pound shops and small branches of national multiples. But it was alive still, and pushing my way to the bus stop wasn't easy in the Saturday afternoon crowds.

In some ways, Pymmes Brook defeated me today - I almost made the full length of the surprisingly resilient little stream, only to be thwarted by the heat on what I almost considered home turf. As the 149 bus trundled slowly towards Liverpool Street, I thought of the confluence with the Lea spied on other walks, a reeking culvert swinging alongside the river and finally joining it at Tottenham Hale. I thought of the tributaries I'd happened on - the Salmon and the Bounds Green Brook - and how they too deserved the honour of a walk. What had seemed to be somewhat inert amble across North London had ended up being the key that unlocked the territory I'd been unwittingly marking out for almost a year. Pymmes Brook itself is an unsettled stream - variously known throughout the last millennium as Medeseye, Millicents Brook and Bell Brook, its changing name and sometimes shifting path to the Lea appear to have confounded plenty before I arrived. London still has so many secrets to give up.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

In an odd coincidence, John Rogers walked the brook in the reverse direction for his series of excellent Youtube videos. You can see his progress at The River of No Return.

I'm back where I ended my last walk, in Ilford. This morning feels a little different - arriving by rail into the Town Centre I have only the vaguest memory of how to get to the River Roding. Those first few moments of the bus journey a few weeks back were spent recovering from the deluge I'd been caught in, and the subtleties of the topography were a little lost on me. I sensed I was close though, navigating by the two tall glass towers of Pioneer Point which dominated the view from Redbridge on my last walk. Sure enough, there was the river sliding inauspiciously between British Telecom's Mill House offices and the North Circular. Marked only by a flourish of green between the buildings and a tiny blue sign, the river has calmed to its usual sluggish, benign flow. But as I've already discovered, following the Roding isn't easy or without challenge. The first was to get to the river: passing under the A406 I'm tempted by the concrete slopes beneath the overpass which imply they could provide a walkway at least part of the way to the water. Realistically though, there doesn't appear to be a way beyond the sliproads, so I negotiate some steps down to Grantham Road. Fronted by a series of tall, slightly ominous point blocks shielding it from Romford Road, this Little Ilford estate feels somewhat tense. A couple of older guys chat animatedly on the corner. I overhear a fragment: "feckin' Europe". It becomes apparent as I navigate the estate that Little Ilford is home to immigrants from the world over. It's the very kind of place where BREXIT feels illogical and it's attendant racism cruel - like a double body-blow. I lower my head and press on, passing a couple of young Indian guys systematically walking the streets and checking the wheelie-bins. For what? Between the stubby blocks to the east I spy a dog walker - always a good sign - and at the end of the short street a gateway to the park. I can feel the A406 reverberating nearby, so I delve into the greenery and find a grassy track which runs directly beside the road, undulating with its embankment and following the line of pylons which began to march alongside me back at Charlie Brown's Roundabout. Just like last time, the river is present but hidden. I'm walking its valley, but not its course.

The largely untamed edge of the park is surprisingly bright and warm, and the walking is pleasant. Having a carpet of grass underfoot is a welcome change. It doesn't last though, and I'm eventually deposited onto the gravel track which circuits the much more primped sports field fronting a disused pavilion. A lone gymnast flips and tumbles across the grass as I edge around the park, trying to find a way through to the green space beyond. It turns out there is no way - so, turning back at the tennis courts I'm out onto the backstreets, deposited onto suburban roads named after painters: Reynolds, Dore, Leader and eventually Millais. The promise of a route under the A406 isn't delivered - if there is a footpath leading off the uninviting entrance to builders yards and reclamation specialists, it's well hidden indeed. Instead I turn west, heading towards the broad underpass which takes me under the London to Southend railway line. The bridge is wide enough for a road to pass beneath, but is hemmed in by barriers to prevent all but cyclists and ill-advised pedestrians from transiting into Barking. Unexpectedly, between two arms of railway I find the entrance to East Ham depot - a location I'd passed numerous times on the rails above, craning my neck for unusual stock. Once south of the delicate swan-neck of rails, Stevenage Road turned abruptly west to skirt the apparently disused Leigh Road Sports Ground. Rusting goalposts quivered in the wind, almost crossbar deep in reedy grasses. Across the vast swathe of grass the North Circular hovered on its tall concrete legs, with the lush foliage of the river beneath. A footbridge was again promised by the OS map, but there was no access to the sports ground - a notice offering 'multiple hazards' to any who dared. A deflated gasholder and its outbuildings sat defiantly in the midst of the overgrown space and reflected a strong morning sun back at me. There was definitely no way in, or out onto the river.

Instead I turned east again along the dusty run of Watson Avenue. One side a high fence, regularly dotted with signs declaring the unimaginable and manifold horrors that would befall anyone trying to access the sports ground, on the other a run of pleasant but tired suburban houses. There's no-one to be seen at all. At the end of the street, a steep footbridge climbed directly over the North Circular. No messing around with tiers of stairs or carefully graded accessibility ramps, just a stepped ascent to the height of a gantry sign. Traffic rushed under a threatening sky, broken with flashes of bright light. From the north, the glassy faces of Pioneer Point winked pale sunlight back at me. This crossing of the road was exhilarating - and it marked a return to the river at last. That return was via the menacing and littered Hertford Road, and a dank, debris-strewn passage beside a Big Yellow Storage Centre which lead to another bridge - this time over the Roding. Here the river was broad and slow-moving, approaching its final meanders towards the Thames. On the west bank, a broad well-made path edged the water. North of here it terminated in a blank wall, but south it appeared to continue by way of the curves of the river towards a gigantic Tesco store. I followed the river path gratefully, not even noticing the faint faecal tang on the air. Surfacing to briefly visit Tesco, I hugged the river wall and edged out of their extensive Car Park beside the Ibis Hotel. I had been here before - and with some confidence I strode along Fresh Wharf Road, passing the inert security checkpoint which had concerned me last time. In the interim I'd discovered it shouldn't be this way. There is, theoretically a route along the west bank of the river - but a dispute between the Fresh Wharf Estate and the owners of houseboats moored at Barking appears to have resulted in it being blocked. While court action has secured them access to their homes, the through-route remains blocked. Instead I turn east again beside the institutional grey block of the Police Custody Centre, heading along a well made path which runs along Hand Trough Creek. Behind the building, hatless but fully body-armoured Policemen smoke committedly between shifts. I emerge at the gated entrance to the moorings and cross the weir by way of the lock gates. I'm finally east of the Roding and with a fairly good path to walk which appears to have been constructed when the modern blocks of flats which front the river were built. I wonder at these places - innocuous, tiny properties packed into serrated blocks which tower above the sluggish channel. The location is promising enough: looking out over the vast sewage complex at Beckton and its neighbouring leisure park offering of American diner and multiplex cinema. Ahead, the A13 crosses on a low concrete bridge, and my pathway is soon pressed up against the wall of the overpass, vegetation hanging above. I emerge at the bottom of a footbridge I'd crossed on my A13 walk, the road seething beside me. I felt like I'd come home.

It was oddly comforting to cross the footbridge over the familiar surge of traffic, watching my hand blacken with heavy particulate as I ran it along the guardrail. I'd been away from my A13 walk for a while now - trying to determine the logistics of the long rural sections ahead - but seeing the road churning along beneath me and remembering a successful walk here made me want to return this part specifically. As I head east briefly towards my turning, a host of wild poppies colonise the mesh of a fence. There is life here, on the edge of things. As built-up Barking gives way to the flat, empty riverside plains of Dagenham, River Road turns south to edge along the Creek. As I trudged out to the junction where I'd turn, I noted a little knot of housing trapped between the road and the industrial area. It must feel strangely embattled here in what remains of Creekmouth - once a tiny village at the confluence of Thames and Roding, now more of a conceptual sales pitch for industrial sites which might one day be served by the Overground. These houses are an outpost - neither here, nor especially there. Creekmouth is gone, buried by refused and scrap metal. Once into River Road, the landscape quickly flattens out into low-rise brick units of industry; The junction crosses the Mayes Brook at an oblique angle which makes its last dive between the back gardens of houses to reach the Creek. The river isn't present at first - after passing under the A13 it makes a brisk eastward turn to run parallel to the Thames briefly, almost resisting its final destination. Eventually though, road and river are running alongside each other and the broad swathe of industry on the western side of the street is all that separates me from the muddy channel. River Road seems to run on forever, a long straight canyon of dust and debris. Piles of fly-tipped house clearances regularly interrupt the path - and one of them partially hides a globe: its dusty continents and battered reliefs peeking out from under the rubble. I finally reach the Waste Transfer Facility which by my calculation borders the Creekmouth Green Space - and it is an utterly horrible last barrier. An evil-smelling swirl of black liquid runs down the sloped entrance road and pools across the footpath, eddying rainbows of oils and fats twinkling up at me. The smell is incredible. Acrid, decaying refuse, sweet hydrocarbon, musty ancient river silt and the human tang of sewage. It fills my nostrils as I push at the creaking gate and walk up the rise towards the bank. I thought I'd built up a resistance in my years working on the edges of the care industry, but it overwhelms me sufficiently by the time I reach the river that it is beyond a mere smell anymore - now it's inside my head. I wonder with some horror whether I'll be stuck with this reek in my nostrils forever? It's an unfortunate time to be awestruck too as I turn, slack-jawed into the open at last- but the sharp-intake of tainted air is worth it: the Barking Flood Relief Barrier towers overhead. Up close, it is notable that the slender concrete pillars are studded with portholes. The idiotic capering figure on the Environment Agency logo shimmers in the haze of heat and pollutants atop each tower. Between the towers, the Isle of Dogs is framed perfectly in the distance. Beside me, the sweep of the Thames takes up the Roding's waters - now a broad estuary in its own right, but dwarfed by the might of the greater flow. I've seen wider vistas further east - bleaker, emptier frames of sky and river - but the end of Barking Creek has an end-of-things quality. I feel like I've walked a long, often fruitless trail from Debden, spending more time navigating the twists and turns of suburban East Ham and Ilford than I've spent on the bank of the river. But hemmed in by the infrastructure of the twentieth century I've honoured the course of this persistent watercourse. It's time to head back.

I'm waiting for a bus on River Road when the rain starts. A small group of Central European factory workers dash over to shelter under the awning of an industrial unit where they converse languidly about BREXIT with regular shrugs and shakes of the head. I stay out in the refreshing storm. It won't last, and the cool clean rainfall is welcome. I see rivulets of black trickling from my hands where I'd picked up the road grime, and I smell the curious but never unwelcome aroma of dry dusty pavements getting wet. The bus finally arrives and we all board - heading back to civilisation and away from this spot which most of us would only ever visit under duress. Almost everyone except me.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

As the Central Line train howled and screeched along the interminably long section between Stratford and Leytonstone, I mused on my hasty plans for today. Again I'd be drawn to the north-eastern fringe of London - to the area where pale green and white expanses fill those pages of the A-Z with no continuity markers at their edges. My musing on the comfortable hamlets on the edge of Essex a month or so back had brought me back to the map to consider their alignment. This in turn drew my eye along the next sliver of green to the east - the Roding Valley. Of course I'd encountered the Roding before almost exactly a year ago, at its estuary where Barking Creek tumbles into the Thames. The reek of sewage and industry seemed very far indeed from this twisting green ribbon, opportunistically squatted by the sinuous M11 and its feeders, which invited a visit. A year ago at the edge of the Creek I'd resolved to add the river to my list of walks - but it's passage seemed distant and less important then. Today though, still spinning from the confusion of a testing week at work, it felt like a perfect target. It seemed a simple walk on the map too...

The Central Line in West Essex is a curious, twisting railway formed from a mixture of extensions to the original Central London Railway and the annexing of former Great Eastern Railway branches. Far from the centre of anything, a strange, post-war feel lingers around the stations on the line's extremities: enamel roundels resolutely remain on platforms and white painted canopies still run the length of the tidy, red brick stations. Only the presence of ticket gates and Oyster readers shoehorned unforgivingly into ticket halls reminds me that I'm in the 21st century here. Debden is no exception. A tiny station on the very fringe of the capital conurbation, the last stop before the Central Line flings out east to Theydon Bois and Epping. To the west of the station the commuter village straggles along the road out of town, but to the east there's nothing but countryside and motorway. This is where I'll start walking - here on the edge of things. The road is marked for Epping and Ongar - five and ten miles away respectively. Ahead of me the carriageway dips to pass under the M11 and then onwards into the rolling hills of Essex. The view couldn't be more English - a concrete slash through a green undulation. A little before the motorway crossing I turn south, a farm gate beside a battered sign for the Roding Valley Way leads onto a track which soon disappears into tall grass. The narrowest of ways worn in previous seasons, slowly growing over. I plunge in, realising I'm really not prepared for this walk in some ways. The noise of the motorway is still present, but muffled by the greenery. A distinctive chimney-sweeper moth flits across the path. Despite the line of tiled rooftops in the near distance indicating Loughton, I'm alone. It's been difficult to relax this week - sometimes painfully so - and the quiet hum of grassland swishes and chitters is remarkably soothing. The regular thrash as I beat through the grass, following the indistinct trail is satisfying too. My walks have taken me to the very edge of the city on plenty of occasions - but this is by far the most rural location yet. Glimpsing the shallow but broad stream of the Roding for the first time, I'm struck how clear the water is - and how the riverbed is mostly free of human detritus. The river bucks and curves in a wide, flat valley here - perfect for railway and motorway building - and they both flank its course along the north-eastern edge of London, hemming in the valley, but oddly protecting it too - making the narrow, irregular belt of green difficult to develop. Instead it is a ribbon of municipal playing fields, sports clubs, public parks and allotments - and sometimes just a rough scramble of grass and earth, tall reads and water-meadows. This is really somewhere rather special.

It soon becomes pretty clear that this walk will follow the course of the valley floor rather than hugging the bank of the river. The path casts me westward, out of the grassland and into a neat playing field. The ubiquitous joggers pad by and dog walkers watch their animals capering in the water. Near a cricket club I spot a tiny bridge arcing over the river, dedicated to a local politician - I take a picture but continue to walk the western bank. Oddly, this bridge could have saved me from a diversion and kept me near the water - but instead I follow the path, hoping that the gap in the line on the map is an omission. It seems to be at first - plunging me along a well-worn track between the river and a lake. I'm confronted suddenly by a fisherman barking into his mobile as he strides back and forth: "I had to drop the boy off at Heathrow.... Nah, three hours before departure now..... Can you facking be-lieve that?". I emerge into another playing field and skirt the edge, following a clearly beaten path to its south-eastern corner. I trust the faintly worn desire-line here, leaping a little ditch and ending up on a rough track where the Roding passes under a lane bearing its name. There's no way through, and no way onto the lane. I follow the track to another frustratingly locked gateway before retracing my steps over the ditch. I finally resort to thrashing out of a tiny but well-trodden gap in a hedgerow onto a beautifully manicured cricket pitch. Interception seems likely - so while I edge around the boundary rope I rehearse arguments about the inadequacy of the map. Checking later I noted that there was another bridge which would have taken me into the environs of a nearby health club - but ultimately further away from the water. My wish to walk as close to the river as possible was, it seemed, drawing me away from it.

After establishing that there was no immediate continuation of the path, I struck out west, into Buckhurst Hill. I broke into a sweat on the gradual rise, realising that it was in fact getting hot despite the grey skies. I decided to pause and apply sun-cream at some point to avoid the strange stealth-tans I seem adept at picking up. Before I reached the main London-bound road I turned aside into suburbia, following Alfred Road and the wonderfully riverine Cascade Road until a tiny public footpath took me back towards the river. Hemmed in between overgrown allotment gardens and the river, it was cool and pleasant - and I hoped I could at least follow the course for a while. The trees soon opened to reveal the great brick archways carrying the quiet Hainault Loop of the Central Line over the valley. The red arc above me felt solid and surprisingly broad for a two-track railway serving the quiet settlements of the valley. I passed under the arch and immediately faced a choice - turning east and crossing the river, scrambling up a slope beside the bridge, or pushing on through an overgrown track between waist-high nettle beds. I was determined to stick to the west bank - more by instinct than judgement - and because the eastern route appeared on paper at least to meander out of the footprint of the river and motorway which had drawn me this way. A few metres and a sharp turn into my daring jungle mission I admitted defeat and turned back. The nettles were waving around my ears now, and the path becomes less distinct the further I go. There was no clear view of how far ahead I might find a way out of this, so it was back to the viaduct. I emerged, covered in seeds and pollen, sneezing and frustrated. The only sensible way - it seemed to me - was up the bank. I scrambled up, my boots doing fine work in keeping me vertical until the very last few steps when I felt like I was about to slither back to the foot of the bank on my belly. My hands grasped pointlessly at strands of reedy grass in some sort of strange faith that just grabbing a hold would stop my tumble. Instead, instinct kicked in and I pitched my not inconsiderable bulk forward with an unseemly grunt. Using momentum to carry me over the brim of the slope, I stumbled ungracefully into yet another private sports ground. The rugby pitches of Bancroft RFC were being manicured and primped, posts re-cemented. A tractor puttered along the southern fringe trimming tall grass. Unsure if I should be here I took courage from a lone dog walker circuiting the pitch and press on along the northern edge, heading diagonally across an unkempt patch of ground to reach the driveway and to escape without being apprehended. Once back out on the street I started to feel frustrated - could I have pushed on and found a way through? Should I just have accepted the eastern bank was more walkable despite the diversions and meanders away from the river? After all - here I was, once again in a pleasantly dull, suburban street with the river already some way behind me. I turned south and trudged on. The mix of interwar council housing and the larger detached properties were comfortingly monotonous. The occasional "Vote LEAVE" posted reminded me of the demographic of this edge of Essex territory. Streets were closed for a Queen's Birthday street party, bunting dangling from the 'temporary closure' notices. At the end of Oxford Road there appeared to be a pathway which led to a bridge which would get me to what appeared to be a much better kept path on the eastern bank, and which seemed to continue much further without interruption. I was back on course...

For a while, at least - the pathway was clearly marked Roding Valley Way and after an unpromising dog-leg around a sports ground, gave way onto a pleasant public park. I could see my route ahead disappearing into the trees fringing the river, so I decided to rest a while and apply sunblock. The dull ache of the clouds was breaking and I sensed a warm afternoon ahead. It felt portentous and stormy. I watched a huge, muscled black guy conducting what appeared to be an endearingly tender conversation via mobile while his slavering Bull Terrier worried him to throw a ball despite its apparent inability to stumble along at more than a few inches per second. Finally I decided it was time to press on, and headed for the bridge - only to find it gated and locked. There seemed to be no reason - it was in good repair, and the path on the opposite bank of the river was in use. I turned back again, passed the drooling dog waiting for its next low-speed chase and headed into the park. As I followed the long driveway from the strangely serrated roof of the visitors centre to the street, a police car edged along ahead of me before spotting a suspicious rough-sleeper in the hedge and peeling off across the grass to investigate. A little crowd assembled - but I headed for the exit. This stretch of the walk had been frustrating and I wanted to escape the suburbs. I turned onto the wonderfully named Snakes Lane East just as the Police car left the park and passed me, having left the rough-sleeper to his own devices. As I waited to cross the street, a car reversed out of a driveway at ludicrous speed, sending a cyclist lurching across the street almost into the Police car's path. The driver seemed oblivious to the near-miss and stopped, signalling the Police car to pass by. The officer shook his head and motioned him back into his drive, turning to follow him. By the time I passed the scene the driver was already yelling about it being "racist" to stop him - at which point a surprisingly imposing Asian Metropolitan Police officer began to unfold himself from the tiny car, much to the surprise of the driver. I left them discussing his motoring skills as I turned onto the busy dual carriageway of Chigwell Road - noting that among a row of tiny suburban shopfronts, next to a self-declared Washing Machine Repair Specialist, was a firearm dealer. The incongruity of the trade in ammunition and weapons with the mock-tudor frontage and the suburban location immediately played into the Essex tradition of low grade gangsters and tooled-up small-time criminals. I struck out for the Esso station - expecting at least to get an expensive refill of my water bottle and an ill-advised snack. As I approached, I noted that nestled between the filling station and the motel-like Broadmead Baptist Church was a narrow pathway with a carved Roding Valley Way arch. So, once equipped with terrifyingly expensive provisions, I edged rather carefully into the dogshit strewn channel between high razor-topped fences, which swiftly opened up into a narrow bridge over the still clear-running Roding waters. It was good to be back with the river, even if my path was going to run a little way from it for a while longer. Ahead of me were the dividing lanes of the M11 with the tiny stubs of the never-built M12 between them. The first carriageway was burrowed-under by way of a pitch dark underpass with the second soaring above me on high posts, leaving a dusty concrete plain beneath. This was as close as I'd get to a picnic spot, so I took the opportunity to eat and review my options under the shrill trauma of traffic desperately slowing for the end of the motorway, or accelerating out of the city's gravity.

I was in the midst of the turmoil here - in a widening apron of negative space on the map left by an incomplete road scheme. The Abercrombie plan for London came to a halt above me in concrete reality. This spreading triangle of land should have seen the carriageways of the M11 continue south - heading for the Inner Motorway Box at Hackney Wick. Instead, the flyovers describe a series of graceful but unnecessarily complex arcs, piling through-traffic onto the North Circular while city-bound travellers are deposited onto Charlie Brown's Roundabout. Named for a pub which was demolished in 1972 to accommodate the enlarged roundabout and tangle of sliproads, this provided a neat historical arc linking me back to my other walks. Charlie Brown's original pub was in West India Dock Road during the heyday of Limehouse as a churning confusion of day-paid dockers, furloughed sailors and ungoverned immigration which would curl the toes of Farage and company. A few years after the original Charlie Brown - the 'Uncrowned King of Limehouse' - died in 1932 his son upped sticks and headed for Essex like all east-enders made good, relocating to the pub in South Woodford but retaining the historical name. In a cruel twist of fate, the original building survived this new venue, but was finally claimed by another road scheme being demolished for the building of the Limehouse Link tunnel. Opened in 1993, until recent times this was the most expensive stretch of road ever built in Britain. In the same period, improvements were being hawked which included the much compromised M11 Link Road - which, when finally built, settled the sorry tale of the south end of the motorway with massive demolition and destruction of long-standing communities in Leyton. It also signalled the start of a series of organised anti-road protests which have dogged road schemes ever since. These strange sequences of events - the cycle of blight and destruction, of inheritance and self-improvement - seem to sum up this part of the world for me.

My own engagement with Charlie Brown's roundabout was to carefully pick a safe route around its edge, finally finding myself above the Roding again as I turned south briefly onto the continuation of Chigwell Road. Somehow, beneath the stacked layers of flyover and roundabout, the winding river kept flowing - only a little battle-scarred by rainbows of fuel and run-off in the process. Finding a tiny gateway, I turned aside and once again found myself on the western bank, the path edging around the sliproad carrying eastbound traffic onto the North Circular. The little cliff caused by the curve of the stream encountering a sloping panel of supporting concrete made a strangely attractive prospect under the brutal weight of road above. A line of pylons marched into the valley here - and would accompany me on this stretch of the walk like a guard of honour. From here I was walking west of the river but east of the road, in a narrow channel of green which gave occasional glimpses either down into the deep, lushly weed filled valley where the river ran, or up onto the nearby carriageway of the A406. The path tracked the road, used only by me and a small band of squirrels which blithely zig-zagged in front of me. It was cool and, despite the drone of road noise, curiously peaceful here. On the opposite bank a disused pumping station stood on the otherwise surprisingly undeveloped bank, gleaming yellow London brick in Spring sunshine.

I finally passed under the A406 a little north of Redbridge Roundabout, by way of a strange concrete bridge carrying both the sluggish river, its towpath, and a broad roadway which was presumably above the flood level. Here I made some grave navigational errors - emerging from the underpass at the roundabout and confidently trudging along the edge of Royston Gardens, I lost my nerve at the entrance to allotments with a "no unauthorised visitors" sign. I think I was mostly just convinced that a way through just wasn't possible. Instead I backtracked, at first to try to access the park via Royston Gardens - which seemed impossible, and then to review my map: only two routes sprang out as potentially possible I elected to pass back under Redbridge Roundabout and exit via Wanstead Park Road which runs parallel to the North Circular - not quite so long, but seemingly offering a link back to the river. Sure enough, after trudging the long, quiet street and navigating the chain of off-duty cabs and the dumped remains of beds and freezers, I found a curving bridge over the main road which deposited me on a network of paths in the green space running along the rivers' edge. I was soon back in the cool, mossy tunnel between bushes and riverbank. A little way along, beside a sign announcing the entrance to Epping Forest, I met a Polish family and had a good-natured but strange chat about whether any large dogs were up ahead. Their tiny mutt capered around, clearly not up for much of a scrap this time. Underway again, I found myself sandwiched between allotments packed with glittering makeshift bird-scarers and the edge of the City of London Cemetery. A strange fluttering noise above alerted me to the beginnings of a rain-storm, the canopy of mature trees providing shelter and preventing the drops from reaching me. The river was parting company now, heading south-eastward into Ilford while the Aldersbrook accompanied me south. Rather unexpectedly, the brick viaduct carrying the railway to Liverpool Street loomed ahead, with a long underpass allowing access south of the tracks. As I left the tunnel I felt great spots of rain begin to fall. By the time I reached Romford Road, the sky was black and the rain was stinging my face. I put up an umbrella which fended off the worst of the tumult, but soon seemed to be letting water in too. The rain continued. The gutters filled and motorists took turns to accidentally - or in some cases not so - spray waiting pedestrians. Busses slowing for the stop kicked up a huge wave in the roadside gullies. I thought about moving on - heading for Ilford - but it was horribly wet still, and worse once out of the lee of the buildings. I waited it out under a brolly. Others had been luckier, finding telephone kiosks or spots under shop awnings. By the time I considered the torrent had abated enough to move on, my lower legs were drenched, as was my back and rucksack. I slurped away through a tide of water running on the pavement - there was no way I could walk on to Barking now with the weather still uncertain and the way not fully clear. I cursed both the weather and my ill-preparedness for it. As I slogged the final few yards up Ilford Hill I noticed people wearing sunglasses, dripping shorts and skin-like wet t-shirts heading my way. We'd all been caught unawares it seemed.

I failed to dry out on the bus to Barking, or on the diverted C2C service into Liverpool Street which I'd caught just to cover an uncommon bit of railway line. I even stayed damp after an extended coffee-layover at the station, my trouser-legs flapping moistly around my ankles in a strange and uncomfortable fashion. By the time I walked up to the ticket gate at Paddington some three hours later, there was still a tide-mark of damp on my shins, my shirt still clung to me. I passed a badly mangled ticket, rescued from my soaked bag, apologetically offering "I'm sorry....the rain, you see....". The gateline operative glanced oddly at me and muttered as he passed me through the gate "RAIN? But we ain't had any here!". I wearily settled into my seat, feeling a tingle of the strange and pervasive British guilt that such interactions often carry - where I'm not at all to fault but feel a need to fix things. I'd last seen the Roding as I walked to the bus stop in Ilford - passing under the roadway, its sluggish meander now a surprising torrent of water. But for today, it had thrown me off the scent once again. The Roding is assuredly not one of London's mythologised 'lost rivers' - although it's often hidden, sometimes in plain sight under a pile of stacked motorways, or behind a screen of suburban villas. Today it refused to give up its secrets easily.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Meridian to Marsh - Breaking the Radial Prejudice

Posted in London on Saturday 7th May 2016 at 11:05pm

It had been widely touted as the hottest weekend of the year so far - and inevitably the comparisons with the usual holiday destinations were being dusted off. Why wasn't I heading off to the coast? Or somewhere nice? As I rattled north from Liverpool Street under blue skies, I pondered just how much these represented genuine comparators? I was heading for Chingford on a largely unplanned walk which would, I'd absent-mindedly guessed, take me down the eastern side of the Lea Valley. A parallel to last months' walk - but in very different territory indeed. Testing my foot on the concourse as I wandered over to the platform was a relief - I could probably make a decent distance today. But to where? A walk without an end point and without a clear idea of how long it would take felt surprisingly refreshing. I wouldn't trade a week of lounging in the sun for a day like this. It was time to get lost...

Chingford took me by surprise. It perhaps shouldn't have - we'd visited some of the neighbouring areas before and seen the surprisingly fashionable High Streets of Woodford and Loughton. These enclaves of the well-to-do and entitled clinging to the ridge on the fringe of the city have evolved to provide what they think they should want: good quality speciality foods, artisanal products, upcycled furniture and exclusive but overpriced clothing. I bought socks I could barely afford and left swiftly as I recall. It was in pondering the similarities between Chingford's busy High Street of restaurants and boutiques and those other locales that I realised I was roughly in the same part of the world: that uneasy transition from the suburban fringe of London to the Essex 'bling belt'. I tend to see London in terms of the radial spurs of its transport network, and generally I've flung myself out to these extremities only to perform a flag-in-the-territory claim on the track. I remember a feverish, sickened visit to the quiet outpost of Epping, even further beyond the fringe - but it still looked and felt like London - the same trains, the same roundels and lettering on the station's running-in boards. But over the fence the community couldn't be further from the city either in composition or attitude. Years of walking the city have begun to challenge this radial prejudice - I've skittered back and forth, from high ground to valley, from borough to borough, west to east and back. I've chased canals, rivers or just unlikely myths of place. I've begun to learn how things fit together - indeed, how they sometimes don't - and how the tone and tension subtly changes when imperceptible borders are crossed. In this I consider myself luckier than some of the natives - those who stake their claim on a territory early on and don't ever stray. This is, after all, a city where gangs organise their bloody rucks on the relative administrivia of the outward postcode zone. So Chingford, E4 felt just like those other monied hamlets that peppered the ridge between the Lea and the Roding as it petered out into Epping Forest. But it was different too - it was linked back to the city much more directly by it's long stewardship of the forest.

I left the station and turned with some reluctance away from the restaurants and shops towards the wide span of rising green space which marked the edge of Chingford. Resisting the urge to delve into the forest and explore the ancient hunting lodge, I struck out along a row of impressive Victorian villas which oddly fronted onto an unmettled, unadopted track which had seen better days. I satisfied myself that it probably played havoc with the suspension of the low-slung Mercedes and BMWs which lined it. Occasional dog walkers passed me by, wrapping the leather around their hands to prevent the bored animals from chasing errant golf balls. The ground began to rise as I passed the last green of the golf course and the path disappeared between trees, delving into a thick wood on the crest of the hill. This was the edge of Epping Forest, once part of the vast Forest of Essex which spanned great swathes of the county. Under the trees it was cool and damp, strangely and refreshingly quiet. The road noise was gone, birds twittered and other creatures skittered around in the brush. There were no more walkers now, and out of the sun there was a pleasant chill to be felt. The path opened into a clearing, with a well-worn track leading north into the forest - but I knew I wanted to head south and east, so I took a less clearly trodden way finding myself skirting a huge bowl surrounded by mature trees and requiring a bit of a breathless scramble. I thought about a retreat, but decided to press on, and was rewarded with the most wonderful experience. As I climbed the edge of the bowl, the trees framed an opening to the east. A wide expanse of grass stretched ahead, falling away in a long sward between the trees. Ahead of me sat two granite obelisks, one huge and imposing and one squat and discreet. They marked the Meridian line - one accurately, the other as an approximation with a dedication to T E Lawrence affixed. The view along the meridian was obscured by trees, but as I turned the hazy sky opened between the ranks of trees and the view west across the shimmering Lea Valley was revealed. The Chingford Reservoirs close at hand, vast expanses of glittering blue-grey water, and beyond them the shaded towers of Tottenham and Edmonton. Further afield the sprawl of the northern suburbs rising on their high ground turned into a dark smudge on the horizon. Looking a little south, the familiar brooding outline of the Isle of Dogs was a sketched-in detail on the horizon. Here, above all this and removed from its pulse and drag, I could appreciate the absence of London in a way I'd not achieved slogging the long, flat marsh paths out of Essex on the trail of the A13 which never quite seemed to shake off the city. Here I was aware of London as an entity, a thing with boundaries and a definite extent. I'd answered the question I'd posed myself so often: is this London? Pole Hill wasn't London. It was near the city, but not in any sense of the city. I spent a long time looking at the horizon, walking carefully down the grassy bank to another open space where views across the Lea Valley were even better. I could have stayed here for a long time. I felt a sense of calm and content I'd missed these past weeks. I felt a strange swelling of pride for a city that wasn't mine.

But I wasn't quite done with Chingford - or with climbing. Leaving Pole Hill via a gap in the hedge I tumbled out onto a narrow lane of bungalows. Cars were being washed, double-glazing renewed. Any mystique accrued on the hill was lost as I turned south passing a grimy concrete office block as I headed back up the hill towards Chingford Mount. I thought about tackling the climb in one, lung-busting push - but settled for paying feigned interest in some railings half way while sucking air heavily. Not that I was particularly conspicuous here just now, the only pedestrian not using motorised transport to climb the rise. That changed as I delved into the side-streets. There were walkers here - but they fell into very specific groups. There were those heading for their cars, toting a key-fob ahead of them as a form of proof they didn't need to walk, and giving apologetic raised eyebrows as some sort of fraternal shared complaint about the parking. The others marshalled dogs. Glazed eyed trophy animals which they inelegantly harnessed using two hands where necessary, preventing the animals from lunging guilelessly at a human which wasn't enveloped in a cloud of scent or aftershave. Here, as I plodded past the villas with electronic gates and multiple garages with my rucksack and water bottle, I looked like trouble. I wasn't sorry to get into the environs of the cemetery - a much more down-to-earth zone filled with smells of Indian cookery and the dust of continuous home-improvement work which likely lacked the formalities of planning permission. I slipped through the gates and into the eastern part of the graveyard, a crowded and tumble-down cluster of tombstones around an austere but peaceful war memorial where I passed a moment and surveyed the surroundings. I wandered a little here before braving a walk into the newer, western plot. This was wholly different - shiny black stones etched with photographs of the missed, a festoon of celebratory flags from the just passed Orthodox Pascha, elaborate and frequently refreshed floral tributes. There was something of a carnival atmosphere, people putting serious work into tending graves which were investments in themselves. There are of course celebrities here too - and I'd be lying if I pretended not to be curious about the presence of the Krays, reunited by prosaic and unremarkable deaths despite their mythology. However, I didn't get near them - there was a queue of young Spanish tourists lining up to gingerly touch the gravestones, awkwardly positioning for selfies with both brothers' memorials in the background and their lurid raincoats and multihued backpacks reflected in the marble. I felt a brewing over-reaction towards this most un-British of responses to death, which made me feel surprising disgust at my own curiosity too. It was time to move on, leaving the humid greenery of the cemetery and heading for the street, abandoning the crowd around the grave.

From here, my route was mercifully down hill following the fall of the Lea Valley towards the Thames. I took the long straight route of Waltham Way, a traffic-clogged approach for the North Circular lined with mid-century homes giving tantalising glimpses of the reservoir beyond. During the gentle descent I became increasingly familiar with a stretch of seven or eight vehicles which would pass me, grind to a halt and then be overtaken at a much slower pace as I caught up with them. Towards the junction of Waltham Way and the North Circular the pleasant suburban feel falls away as it becomes an access road for a number of industrial estates, with a stretch of tired Victorian shopfronts where I topped up on water but failed to find food. The lack of planning I'd done began to trouble me here - the A406 was a huge, six lane barrier curving across my path. I knew of a footbridge a little east towards Crooked Billet and decided to head that way, calling in at an expensive and grubby petrol station along the way for sustenance. I finally found the slender crossing and slogged up the ramps to survey the land from above. A huge Costco dominated the view west, taunting me with comparatively low prices. To the south I could see the scrubby edgelands which fell between the boundary of Chingford and Higham's Hill, blighted by the presence of the road beneath. From the train this had seemed intriguing - one of the odd and unremarked corners of undeveloped land in this part of London. Now I just needed to find a way to get there, following the signs for Folly Lane and the Islamic Cemetery and passing a much superior and more reasonable service station too. Once out of sight of the main road, Folly Lane quickly dissolved into a dusty chasm of fly-tipping and builders rubble hemmed in by uncontrolled hedgerows and an inexplicably prolific crop of security cameras. I felt instantly more comfortable - this was more like my usual territory, and I sensed water close by. The eastern edge of the road gave way to a scrubby and damp meadow where stoic ponies grazed and eyed me with disinterest. I passed the Islamic Cemetery, a basic but impeccably tidy facility where silence and respect were encouraged. Coming towards me - and reassuring me that the unmarked path did indeed continue beyond this point - a dog walker kicked at the sign for the cemetery and rolled his eyes. I pretended not to understand the casual non-verbal racism and hoped not to hear the click of a slavering terrier being released. Happily he was much too busy being disgruntled to care, and I made it between the bollards and onto the path which edges around Highams' Hill - a seemingly pleasant but dense cluster of streets hemmed in on two sides by the threads of the Lea and the Banbury Reservoir. It feels almost as remotely disconnected from London as Chingford did. A community which looks east and north, rather than inwards towards the core it can't easily reach. The path officially turned south here to access the housing, but I could continue by passing under the splayed legs of an electricity pylon which towered over me. I stood at its centre while I chose my route - in the curious belief that perhaps it could impart some wisdom: I would continue to walk beside the reservoir, soon coming alongside the concrete edged channel in which the Lea flows here, tantalisingly close beyond a railing. The road swung back east here, but a path and an unlocked gateway ahead appeared to continue my route. It's in this sort of circumstance I'd usually take the safe option and regret needing to create some new route to reclaim my territory. Today though, I was aware I had no plan and didn't really know where I wanted to end my walk. Reasoning that I was in the midst of a dense, well-networked city and couldn't reasonably stray far from a route back to the familiar, I pressed on. The path ran along the edge of allotments and the backs of houses which faced away from the river and the marshes. A municipal railing kept me away from the river's various flows: the Navigation running in a deep concrete rut and crossing the flood relief channel at a complex skewed bridge. The by this point somewhat misnamed Navigation curved purposefully to feed the High and Low Maynard reservoirs while the broader, sluggish and half-dry Relief Channel meandered around them. Eventually my impromptu new route came to an end at a locked gate which provided maintenance access to the reservoirs. I turned east along the track which led back to Blackhorse Lane.

Pausing on the low wall outside a school and unenthusiastically consuming my expensive service station lunch, I pondered the walk so far. I'd never set out to walk this way, only having the vaguest plans around Chingford and perhaps walking the eastern edge of the Lea Valley. Instead, I found the views from my train ride out of the city colouring my plans, persuading me to fill in the gaps between lines and stations, to understand the territory better. I set off south through the industrial zone of Blackhorse Lane, an area apparently curiously proud of its name which was repeated at the top of clock-totems and in retro font lettering on factory walls. With the first aches and pains of my trek beginning to set in, I realised I still had no idea where I was going - where would be a fitting end to this? At Blackhorse Road station I faced a crossroads - I could head west here and cross the valley to Tottenham Hale where I'd finished my last walk, or I could head east on the long slog into Walthamstow. Both would have marked a return to the safety of the city. Instead I headed south along the line of the river, dodging into the suburban backstreets to stay as close to its course as possible. The long avenue of Edward Road, lined with viciously pollarded, alien-looking trees fronted the Douglas Eyre playing fields - apparently being subsumed into the grounds of a new-build academy and firmly off limits. I had to take on faith the presence of the Dagenham Brook and the Lea just beyond the tall Victorian villas which lined the street. As I reached yet another school at a crossroads ahead, I faced another choice - I could plough on south into the industrial fringe which marked the edge of the Olympic project, or I could turn west towards the marshes. The curious magnetism of the marshes won yet again.

A westbound perambulation along Coppermill Lane felt like a reversed time-line of the East End: a gradual winding back from hipster shops with graffiti wall-art and modest boozers, through industrial scale water-treatment to the prehistoric panorama of the marshes. As I headed west, leaving the terraces of Leytonstone behind me, the vast sheets of water which filled the dip of the valley dominated the view. To the north, the island-dotted wedge of Walthamstow Reservoir No.5 and to the south the regular pattern of shimmering rectangles around the vast waterworks complex. This lower reach of the valley has a history of treating human effluent, of turning ordure into water - and its industry has often done much to reverse the process. From the crumbling concrete graveyard of the Middlesex Filter Beds to the vast sewage metropolis at Beckton, the eastern reaches of the Thames and the Lea have always been the axis of waste and regeneration. In the midst of it, this waypoint. Ian Bourn's "urethra of London" fully realised. Passing the mid-century offices which front the waterworks, I dodged cyclists as the lane took on a rural aspect. It was busy with walkers enjoying the sun - the obligatory eastern European couples ambling together along with families braving the midges and striding out towards the marshes. Suddenly I find myself at a familiar spot but viewing it from an utterly different angle. Above me is the railway line from Liverpool Street to Cambridge crossing a low underpass dug out of the marsh. To my left is a gate giving access to the marshes east of the line - a carpark and picnic area fronting a vast swathe of tall grasses and a long straight path which seems to follow the route of one of the long culverted channels of the river. My head aches from the brightness, so I stop and watch trains pass while cyclists try to navigate the low passage without dismounting. People aren't moving now. The afternoon sun has turned suddenly and surprisingly warmer, and they're lying down where they stood, struck and scattered like horror movie victims. Shirts are off, trousers rolled. London is relaxing into an opportunistic summer. I walk on, the oddball in the sweater, tossing sweat-flattened hair back from my face and sucking at the last of my water to wash down painkillers. The end of the walk has suggested itself - Lea Bridge is looming. The skeletal new railway station waiting to reopen just across the marsh, the buses ducking and weaving from the stop. It feels like getting back to civilisation after a walk in the wilderness despite the tide of sunbathers.

Weaving through the Equestrian Centre and out onto the road, I'm glad of the trees fringing the road and providing shade. The painkillers start to kick in, dulling the heat-induced ache and letting my feet throb reassuringly instead. It strikes me that this walk couldn't have happened a year ago - even a few months back. I've grown more comfortable walking these fringes, less given to range anxiety and keener to find the boundaries, the interstitial zones, rather than immersing myself in a received version of the eastern reaches of London. It strikes me too that being lost is a welcome distraction - a little dose of unreality that challenges me to navigate using my wits and my instincts rather than a map. But its straight back to the map I'll go - to plot, to measure and to retrospectively research my walk. Each new turn chosen suggesting an untaken alternative. Another way to get lost.

You can find a gallery of images from the walk here.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.