I'm not a Londoner. Never have been, and it's fairly certain I never will be. My relationship with London is a strange and complicated one - sometimes bordering on reverence, and sometimes borne of a strange distaste. Spurred on by literature and music, snippets of legend and odd coincidences, I've gradually mapped out a city of my own during the last twenty years. This has grown eastwards - from my early timid steps out of Paddington towards the City, then over the boundary and into Spitalfields and Hackney. As my knowledge grew, so did my appetite for the literature and history of the eastern edges of the city. I was hooked, finding untold possibility in every dead end, every scruffy side-turning. Having carefully evaluated this view from safe distances I was sure it wasn't some dreadful middle-class 'slumming' thing. I was genuinely finding myself bound up in the boroughs, and wanting to understand them as best I could.

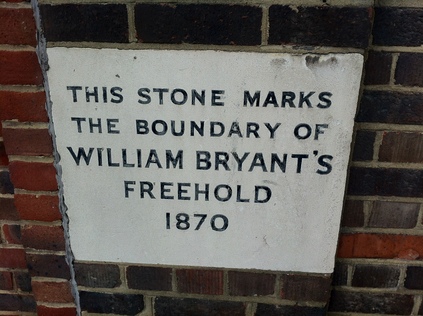

Today was wet, and as I stepped out of Bow Road Station I was met with a shining roadway and trees dripping dolefully on me. I shouldn't be here. I'd vowed again that I'd made my last trip before the Games, but as the activity and focus intensifies in the press - so does my desire to be here. I've got this horrible feeling that it won't be the same again, that this is the end of things. Perhaps it's melodramatic - but it seems like the end of London. My London at least. But it doesn't feel like it this morning, and the margins of Bow Road are as raggedly familiar as ever - the Ferodo Bridge sheltering me as I tap out messages which scud over the channel to a desperate friend. Everyone is on the edge. Turning into Fairfield Road, the leafy quiet descends. This residential corner of Bow has always felt pleasant and perhaps a little dull from the train above, but here at ground level it's a surprisingly busy walk. People shuffle out of their buildings, taking the chance of a gap in the torrents. Once under the railway bridges - carrying the Great Eastern on its run into Liverpool Street and the little used curve from Bow to Gas Factory Junction - the Lexington Building becomes a dominating presence. The ornate gatehouse signals a former use - Bryant and May's sprawling match factory, site of one of the earliest feminist actions in the 1888 strike organised by Annie Besant. Closed in 1979 and left to languish along with much of this part of the city, it is now Bow Quarter. A gated village which has hosted celebrities on the up, and sometimes on the way down. But my journey here is once again related to the Olympics. On top of one of the startlingly tall, red brick watertowers are surface-to-air missiles. Part of a ring of defences for the Olympic Park which do not offer much in the way of reassurance - if these missiles with their five mile range need to be fired, a plane will fall over the eastern reaches of London with all the attendant misery and horror. There is no assurance in the presence of these weapons at all. I circle the building - there is only a glimpse of the hardware available - a sinister presence on top of the building, capable of dealing death - indirectly - to many thousands. The locals are stirring. A pretty, but stiffly miniskirted young woman swishes along the path under her umbrella, finding my shambling presence a worry and crossing the road quickly. A blonde, rakishly housecoated young man smokes and drinks tea barefoot on his doorstep. It's quiet. No vehicles move except the occasional Tesco or Ocado van, and the relentless stream of 488 buses heading for Bromley. I remind myself that's where I need to head too, and speed up my circuit of the building in search of the photograph which sums it all up. I'll know it when I see it. On Wick Lane, a mad traffic scheme has made it hugely difficult for pedestrians, and under the railway bridge it is blocked by a works compound. There is no way to double back through Bow Quarter so I'm forced to retrace my steps. As I pass the gatehouse, two figures silently emerge - both uniformed, one in the olive green of the British Army. My lurking has not gone unnoticed and I have questions to answer.

The light-touch interrogators claimed my presence had "upset the residents". I bit my tongue, thinking how theirs had probably in fact caused far more upset. But I'm allowed to leave unmolested with a suggestion that I avoid the area until September 14th on pain of arrest. There's no paperwork, no proof of the injunction. This is instant service, delivered without a smile. I'll have little choice of course. But I'm late for my meeting with a friend, so I plough on into the rain, back to Bow Road and across into the quiet centre of Bromley. I follow estate paths and quiet residential roads. Families scuff quietly through the rain, snakes of children dawdling, either idly ignorant or indifferent to the changing face of their locale. I come upon the station from the north, and red faced, breathing hard and feeling distinctly old I meet my friend who has agreed to join me for a walk around some of my recent trails. I relate the morning's tale to her amusement, and we head out of the station, alongisde the Blackwall Tunnel Approach road and into Three Mills Lane. We talk about how she is now a Londoner and wants to see the city - all of it. She can circuit Buckingham Palace on her bus to the station, but it's these wanders into the unknown which interest her. I retrace recent steps, wondering just how much of the walk I'll be able to achieve post Lockdown. Our first taste of the Games comes just on the edge of Three Mills - the towpath south of here is closed, the swollen mouth of Bow Creek off limits. Tour groups shuffle damply behind their leaders, still being told there is no means of entry to the Park but that they can see the sights. I wonder where and how, given the route these opportunistic guides have been taking is now severed? Avoiding the groups we wander onto Three Mills Green, the new wholesomely crunchy pathways under puddles of water after the last few weeks of rain. The lock on Prescott Channel is silent, the bridge to Abbey Mills closed. My friend spies the building and is transfixed by it. We'll get there I promise, silently wondering if we can? Skirting the park we cross Three Mills Wall river and take to the streets. My friend remarks how quiet it is, and how it could be 'anywhere'. The calm streets of current and former council properties seem immune to the events just a short walk away across Stratford High Street. The rain starts to sheet horizontally across us. Visibility diminishes. We struggle up the slippery wooden steps onto the Greenway and find a vantage point where the vast temple of the Pumping Station can be appreciated. Its strangely eastern influences seem out of place in the misty, drizzly air. The chimney stumps, inert since 1941, look sinister and squat. Ahead of us Channelsea House towers, apparently unaffected by regeneration and near abandoned. We turn and walk towards the Olympic Park, the increasingly irritating Orbit structure dominating the skyline. The temporary bridge remains defended by razor wire, so we edge down to the crossing then work back towards Stratford. Warton Road is closed to cyclists and pedestrians, so we turn into the Carpenters Road Estate. I get a sudden, amusing realisation that all those railway junction names which seem so exotic and unknown when plotting unusual routes represent this topography. Carpenters Road Junction to Channelsea Junction - and there is on the map at least - a watercourse between the estate and the railway, a ghost of the buried Channelsea River? If so, it is now entirely gone. Culverted in 1958, the river has a legendary past linking it back to Alfred the Great. There is no way through for us though, great iron gates claiming we're "Welcome to London 2012". I've never felt less welcome.

We follow shoppers over the footbridge, descending at Stratford Station. The tide heading for Westfield is a shadow of that sunny Saturday throng I witnessed just a couple of weeks back. The rain, and the threat of exceptional crowds holding them back perhaps. We head over the rust-coloured bridge, pausing to look at the park. "It's horrible, from here at least" my friend remarks. It's her city, not mine - but usually I'd have felt that pang of defensiveness. There's nothing there though, and I agree with her wholeheartedly. We head into Westfield and find a pub where we can catch up properly - The Cow is a strange effort - a glass and metal shed on the edge of the shopping centre, looking out over the Stratford Gate to the Olympic Park. Inside, the exposed utilities are accompanied by amusingly silly wooden beams and lots of bovine memorabilia and signage. Drinks are expensive, but the staff are surprisingly polite. Throughout our conversation, I keep returning to the Olympics - perhaps people are right, and I am obsessed? I mention the fence again and again, it troubles me - haunts my walks, offends my eyes. I explain the lineage of my concerns - from reading early, worrying accounts of what would occur here, through endless crossings and recrossings of the park by rail, and eventually on foot while I still could. An urgency caused by the increasingly draconian attempts to render the park inaccessible. We touch on radioactivity, Clays Lane, the allotments, football pitches. All the old arguments rehearsed again. I try to pitch the difference between wilderness and wasteland. I have a sympathetic audience, but it's all too late. It still feels like the end of London. After we part at Stratford Station, I walk to the edge of the Westfield site. Over the fence near the International Station, groups of children are practicing for the Opening Ceremony in the precincts of the Athlete's Village. The fence is a presence even here. I dare not linger, and catch the driverless DLR train to Stratford, curving through the park, the alignment following old curves of railway lines then dipping under the buildings. At Stratford I change to the older DLR line which uses part of the railway which cuts north-south through Bow and takes me back to my starting point. On route, we linger at the closed Pudding Mill Lane station waiting for the line to clear. In the midst of the Olympic Park, this is a deleted station. Beside us, the piers of it's replacement are half made, work on Crossrail abandoned until after the event. London is on pause. Waiting. I alight at Bow Church and ascend to the street just feet from the end of Fairfield Road, where I began the strangely frustrating journey today. Blocked at every turn, but oddly I want to walk these streets more than ever now. I want to explore every possible route through this complex and ancient district. I desperately want to come back.

Even at Paddington, the Games dominate proceedings. The Mayor's voice - ill-suited to public announcements - lisps and quacks through his urge to travel differently. Pink signs point the way to the park like it's just around the corner rather than a city away, greeters stand idly on the Heathrow Express platforms waiting for athletes and media representatives to arrive. Beside the exit, a new tunnel has opened to provide access to transport for Games officials. I can't remember this passageway before, and any hope of exploring is scuppered by security guards. On the way home, I flick through reports about the Army presence. Anyone who'd walked the area knew they were here weeks ago, and now they're here in remarkable numbers. G4S get the blame for falling short, but it feels like the military were always coming and this is just a great excuse to explain it to the public. And its these things - disingenuous accounts, towpaths suddenly closed, pedestrians banned - which make me wonder if we'll ever get any of this back? Will the towpath along the Lea ever be walkable again? Will the soldiers ever leave the area completely? It's for these reasons that this feels like an ending - like London won't ever be the same post-Games. Looking west from the 205 bus, there is a hint of sunshine on the horizon, but back east it's black and ominous.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.