I've always been a little nervous about guided walks. From the awkward, rather typically British issue of trying to identify your fellow walkers at the outset - ideally without actually asking anyone - to the tricky etiquette of dispersing at the walk's end, they're a minefield. I once thought I'd like to lead walks - the idea of ambling around places I love with a respectful and engaged bunch of people both asking questions and adding their knowledge was attractive, if unlikely. Of course the reality is often different: bored tourists "doing" the sights, loudmouthed know-alls trying to upstage the guide, people with no spatial awareness causing minor traffic incidents. Guiding walks wasn't for me. In my attempts I also realised a simple truth: firstly most people just aren't as interested in the minutiae as I am. I've often thought I was boring or lacked the capacity to engage people - but as I've grown older I realise I'm just engaged differently. I've learned to live with this, and find myself surrounded by people who are at best encouraging, but at the very least tolerant of this. So today I approached a group of unlikely looking people assembling near Tower Hill station with some trepidation. We were going on a walk together - which for someone who jealously guards his excursion time, was a remarkably intimate association with strangers.

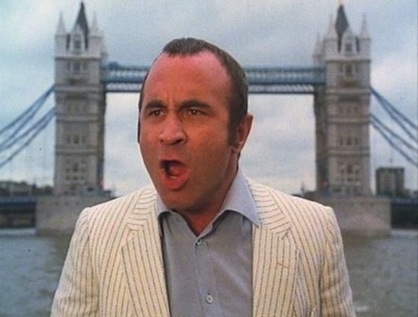

Today's trip focused on locations from The Long Good Friday - the 1980 movie which launched Bob Hoskins on his path towards being the nation's 'loveable villain' figure in Harold Shand, and which almost didn't see the light of day due to the inclusion of the then horribly ever-present IRA as the bad guys. Or perhaps more accurately as the worst of the bad guys - there are no good guys in the film. In some ways, despite the brash edge-of-the-eighties optimism, the glamorous yachts and the presence of some weirdly prescient tropes which would haunt London for decades to come, the movie has no redemptive ending. My first viewing of the movie years back left a couple of impressions - that London was unrecognisable for the most part, and that it kickstarted a good number of British acting careers. John Mackenzie's clear vision that this should not be the London of red buses and black cabs had wrong-footed me. But as I've walked the hinterlands of the city over the years, I've come to recognise Harold Shand's London - sometimes it is buried, sometimes it lurks in the most unedifying areas, often it requires a mixture of research and imagination to conjure it from the anodyne glass and steel of the modern city. But it lurks not far from the surface, buried under the very Thatcherite dream which Hoskins invokes as his yacht passes under Tower Bridge at the beginning of the movie. The regeneration of the docks, the opportunities for investment, London positioned as a European capital - calling the shots, not taking the bullets. Those predictions which must have seemed so outlandish to anyone who knew the dereliction of the Isle of Dogs and Royal Docks in the 1970s, now elicit a gasp of recognition followed by an ironic guffaw: the European dream is close to being over, the '1988 Olympics' which Shand proposes happened - if a little later than scheduled.

Our guide was the placid, knowledgeable and powerfully-voiced Rob, who called the group to order and set out the plan. We'd walk for a couple of hours, visit a number of locations used in the film and chart the progress of Harold's dream towards the Docklands of today. He'd play us contextual clips of the movie on his iPad - so we could gauge just how much had changed and how much remained of Harold's manor. I surveyed my companions - there were of course stereotypes: the older guy who sticks to the guide like a minder and engages all of his time between stops in discussion, the gent with the expensive camera who wanders all over the place taking endless shots of everything but the subject at hand, the middle-class intellectual couple who roll their watery eyes at each other when the discussion has to be simplified or edited for the sake of time or sustaining group interest. We shuffled off, over the messy tangle of crossings outside the Tower of London, over the neck of Tower Bridge where Police were zooming to some sort of incident involving a group of yelling tourists, and towards the Thames near the huge concrete hotel. This was the first point at which imagination would be challenged: we were asked to picture warehouses - full of spice and indigo, a river teeming with ships waiting to unload. Some had waited weeks, some even longer. The Pool of London was jammed and dangerous - haunted by river pirates who took advantage of the vessels stuck here waiting to be unloaded - some in the most violent of ways. London needed new docks and new suburbs to support them - and so St. Katharine's Dock was constructed. By the time Harold Shand was mooring his luxury yacht here, the dock was deserted and in disrepair. Several of the large, impressive warehouses had already fallen to new development and only the Ivory House remained fully intact. Today the view was surprisingly similar if the skyline beyond the warehouses was discounted, along with the modern housing which had sprung into being on three sides of the basin. In the corner the Dickens Inn tumbled towards the docks, its provenance not entirely honest - being some form of reconstruction from recovered materials on a new site. The marina was busy with boats which would have rivalled Harold's for style and opulence. It was clear from the outset that this walk was going to deal in contrasts.

We progressed towards Wapping via the river front, recalling the shot where Hoskins was framed by Tower Bridge as he gave his rousing, patriotic call to 'the right people'. It quickly became apparent that this walk was unwinding two narratives - the fictional world in which the movie played out, and the uncannily similar events which followed just a few years later via the London Docklands Development Corporation. Shand's own 'corporation' fell prey to retaliatory attacks by the IRA and we saw the corner opposite Scandrett Street where, by virtue of a limited budget, a plywood East End boozer had been constructed to be blown up. We stood below, picturing the sight from the ground, where Shand's car had been seen arriving from the narrow street beside the then abandoned school buildings. Just a short walk around the corner we found the squat, yellow brick St. Patrick's Catholic Church. Apologetic and a little featureless outside, the interior was elegant and lofty, with brightly decorated iconography and dramatic columns climbing to a surprisingly lofty ceiling. Outside we strained to see St. George in the East over the rooftops, as the scene where Shand's mother narrowly escapes a car bomb was a composite with Hawksmoor's striking edifice playing the exterior while St. Patrick provides a fittingly non-Anglican interior. We didn't head for St. George this time - but I'd spent enough time stalking the environs to be able to picture the switch perfectly. Around the next corner we found Dundee Street, with warehouses now converted into flats and offices. Above the street, bridges crossed between windows completing the image of gentrified dockland living. It was here however that a young Gillian Taylforth played the young women who discovers a dying security guard nailed to the beams of the floor in a perverse play on the film's title. The religious imagery is deftly done - temptation, betrayal and sacrifice played out in the slightly distended timeline of a single day.

Approaching the Limehouse Link Tunnel, the story shifted from the plans which Harold Shand had for a new city, to the events which took place here in the 1970s - Michael Heseltine's helicopter flying low over the abandoned wasteland on a return from an abortive excursion to Maplin Sands. His development of the LDDC with the plan to free the area from the shackles of council inertia and the too-and-fro of the same old guard in Parliament. He gives them comprehensive planning powers and just enough money to buy land and sell it cheap. At the same time, London Transport scoff at serving the area with any sort of serious service, and instead the Docklands Light Railway springs up - a budget train-set to fit the low-rise developments which are springing up. Heseltine wants to see people living and working here again, but it's slow - painfully so - and far too glacial for Nicholas Ridley who follows him into the Environment brief. He has a new vision: leveraging private capital to spark life into the Isle of Dogs. The Canadians arrive but want the infrastructure before they commit. Soon the DLR is expanded, the Limehouse Link digging begins - possibly the most expensive road project ever in the UK at that point. Slowly the towers climb from the water. But - abruptly - the market crashes and everything stops. The abundance of empty office space across the major cities of the UK and Europe makes a folly out of One Canada Square, the tower which glowers over the island with a baleful pyramid and an ever present smear of smoke at its apex. It may as well have been burning money.

Then the IRA make their own leap from fiction to fact - this time in a genuine and devastating way. On 9th February 1996 the two-year long ceasefire ended with a huge explosion under the DLR on Marsh Wall. Two men, local newsagents, were killed in the blast which left a huge crater in the ground and destroyed one building, and damaged two others seriously. I remember a DLR trip through the area some weeks after the bombing - the shell of the Midland Bank building with its empty windows and flapping blinds standing eerily beside the track as we swerved and dodged around the tight curves between docks and offices. This and a range of other IRA actions in the City of London and Manchester achieved what no amount of government money had managed - it created a market for decent office space. The development of Docklands was perversely rejuvenated and soon Canary Wharf was at the very heart of the plan. Soaring from the mirror-like surface of the former docks, new office towers grew swiftly with the emblems of international banks blinking into life above them. As we arrived at Canary Wharf it was nearly impossible to imagine this was the site of Harold's betrayal in the movie. His blood-soaked stagger from the yacht with a Lear-like howl towards a focused, cool Helen Mirren took place at a point before any of this could be imagined. The deserted dockside with its rank of low sheds along their edge didn't promise this kind of future, and at this point in the movie with his betrayal complete his scheme to bring prosperity seems unlikely to succeed. Now, the impressive brick sheds are the only surviving reference point - housing the Museum of London in Docklands, they are busy with visitors. Across the dock, the glassy torpedo of the new Crossrail Place appears to be moored alongside the office towers, the uncommissioned platforms sitting far beneath the water. The walk ends here, the story complete and Harold Shand's dream delivered despite his almost certain fate at the hands of a young Pierce Brosnan. Using the movie as a lens through which to view the change wrought on this part of the Isle of Dogs was a surprisingly clever ruse, and I can't help but feel that our rather oddly matched group of walkers would never have been assembled for a straightforward 'Docklands history walk'. They might have sniggered and sighed at the names of Conservative politicians of the 90s, but in doing so they missed a point - the plan in its original form was to remake part of London very much in its own, older image. What happened here, what has grown as a strange, disembodied and distinctly transatlantic city beside the city, is as much the result of subsequent governments of both parties' losing grip on the financial sector.

Suddenly, I was alone in the midst of the new city. The group dispersed, even the guide's most ardent hangers on finally leaving him to head for the station. The small square, tucked in beside the replica of the West India Dock Gateway with its elaborate model ship, was windswept and empty. Construction on both sides of the square meant no-one much was heading this way. I tried to decide what to do for the best. The guided walk had taken a little longer than I expected and I'd not thought through my options for the afternoon. I decided to grab a bite to eat before trying to complete a stretch of walking I'd meant to cover for some time - the perimeter of the Isle of Dogs. First I had to negotiate the mall which sits under One Canada Square. I'd been here before, many years ago, and I knew there was a small supermarket near the DLR station. Getting there was a challenge - I'd never arrived at ground level before, and even the concept of 'ground' was less than fixed here. I found a lift and ascended from the sub-zero floors towards the surface, which was in fact the level of the bridge carrying people across to the soon-to-be Crossrail station, finally finding myself at the store near the DLR which was, today at least, closed for engineering works. Purchases made, I retraced my steps out into the broad square and perched beside a cool fountain to eat and plan a little. It didn't take long for a uniformed 'Canary Wharf Estates' employee to take an interest. After wandering around the general area for a little while he plucked up the courage to come nearer. "Going to be long?" he enquired? I took a silent slug of water and said "Not much longer, just having a breather before I walk a bit more". He looked like he wanted to ask more questions - but he was young, inexperienced and a little unsure. I suspect he'd have found it easier if I was a rolling drunk or an itinerant begger - someone he could legitimately move on using the powers he had on the private estate. Instead I was a reasonably polite, reasonably tidy chap who had happily answered his question. "Well, take care then - and no hanging about" he managed before he scuttled back towards the building. I dusted myself down a little, took some defiant shots of the building towering above me, and headed along the edge of Crossrail Place. At the end of the walkway where the building petered out and the dock resumed, things were a little ragged. There are still rough edges to the Canary Wharf estate, and if one walks to the perimeter they soon become apparent. Turning alongside Bellmouth Passage I climbed stairs and crossed a street near empty offices, finally escaping the estate via Trafalgar Way. The staffed sentry post was active, the private police force beckoning cars forward to have credentials checked while flagging buses into the site. I looked across the broad empty area surrounding Billingsgate Fish Market, and across to Balfron Tower and the towers of Stratford beyond. It was a surprisingly sunny afternoon, though you'd never know it inside the estate, where the buildings reflect only each other.

I found myself not far from an area I'd walked some while ago, near Poplar Dock Marina. Ahead was the route to Blackwall and Leamouth, but I turned south cutting through a carpark to regain the A1206 as it started a long curve around the island. It soon became apparent that trying to use the river path was going to be a fruitless and time-consuming endeavour. The path was frequently broken by developments, sending me scurrying back and forth to find a route south. Instead, once over the impressive Blue Bridge I stuck largely to the main roads, with a brief excursion into the Samuda Estate. This rather forlorn range of London County Council blocks from 1965 looked tired and careworn, and at their centre stood the stark and impressive Kelson House. This twenty-five storey tower, made up of neatly interlocking three-level maisonettes, was modelled on Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation, with access via a separate slender tower on its western side. It wasn't as graceful or bold as Goldfinger's similar efforts, and was altogether more workmanlike and British in appearance - a building which could grace any city centre perhaps? That it survives is testament to a tenacious island population who have, on the whole accepted incomers and immigrants rather like any dockside community. However, in the 1990s the area had a period of more chequered history, electing the first ever British National Party councillor in Derek Beackon. Beackon appeared to be as surprised as anyone to find himself on Tower Hamlets Council, and struggled to manage the complexity or scale of work expected of him. Perhaps not surprising as his prior role in the party had been as 'Chief Steward' - effectively the organiser of the team of Skinhead bodyguards who circled the leadership in public. Beackon's 'rights for whites' agenda was perhaps surprisingly aided by the local Liberal Democrats who published their own literature complaining that the predominantly Bangladeshi group rehoused from Limehouse when the Link Tunnel was built were given priority in 'luxury' accommodation. With Labour and the Lib Dems locked in an idealogical struggle during the 1993 election, Beackon crept in by a margin of only seven votes and immediately failed to comprehend what was possible at the local level. His colleague councillors walked out in protest at sharing the chamber with an immoderate and loud-mouthed fascist. When the seat was again contested in 1994, Beackon was ousted by a concerted campaign by Labour, and while the white working class roots of the island persist, there is at least a sense of a shared community in this oddly isolated zone again.

Pressed for time, I began to consider my options. The plan to circuit the island back to Limehouse was possible, but I found myself rushing ahead and not taking in my surroudings. A steady procession of buses beside me on Manchester Road had been reassuring at first - a potential quick way out if time got tight - but now they felt like a nagging pressure. At Island Gardens I decided to rethink my plan. With the DLR out of action the square outside the realigned route was busy with people teeming from the Rail Replacement Services. Beside the shiny, winged modern station the brick viaduct which had originally carried the rails here was still standing. I recalled previous visits, long before the railway burrowed under the river, bailing out here at the end of the line and regarding Greenwich across the river from a bench in the small park. Seized by a sudden desire to relive this experience, I headed into the gardens and found my way to the river wall. The Thames buzzed with life - river buses and motor launches scudding over the brown waters. The Greenwich foot tunnel's domed entrances flanked the park, emerging beside the impressive bulk of the Royal Naval College across the river. Beyond, green space stretched away up towards the observatory. I lingered for a moment, before heading back to complete my loop around the island by bus. There was unfinished business on the island - and much to be explored within the deep loop of river - but for now at least, it was time to head back to the mainland.

Lost::MikeGTN

I've had a home on the web for more years than I care to remember, and a few kind souls persuade me it's worth persisting with keeping it updated. This current incarnation of the site is centred around the blog posts which began back in 1999 as 'the daylog' and continued through my travels and tribulations during the following years.

I don't get out and about nearly as much these days, but I do try to record significant events and trips for posterity. You may also have arrived here by following the trail to my former music blog Songs Heard On Fast Trains. That content is preserved here too.